Introduction

The Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”) celebrates its seventy-fifth birthday this year.1Administrative Procedure Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 79-404, 60 Stat. 237 (codified as amended at 5 U.S.C. §§ 551–706). Its enactment in 1946 was the result of a “fierce compromise” after a decade-long battle between proponents and opponents of the New Deal administrative state.2See George B. Shepherd, Fierce Compromise: The Administrative Procedure Act Emerges from New Deal Politics, 90 Nw. U. L. Rev. 1557, 1560 (1996). See generally Walter Gellhorn, The Administrative Procedure Act: The Beginnings, 72 Va. L. Rev. 219 (1986) (offering an overview of the creation of the APA). Over the decades, the APA has matured to become the quasi-constitution of the modern administrative state. In 1978, for instance, the then-law professor for whom the Law Review’s home institution is named remarked that “the Supreme Court regarded the APA as a sort of superstatute, or subconstitution, in the field of administrative process: a basic framework that was not lightly to be supplanted or embellished.”3Antonin Scalia, Vermont Yankee: The APA, the D.C. Circuit, and the Supreme Court, 1978 Sup. Ct. Rev. 345, 363; see also Kathryn E. Kovacs, Superstatute Theory and the Administrative Common Law, 90 Ind. L.J. 1207, 1209 (2015) (arguing that the APA is a “superstatute” (citing William N. Eskridge & John Ferejohn, A Republic of Statutes: The New American Constitution (2010))). It is thus only fitting that the Law Review editors decided to publish this festschrift to mark the APA’s first seventy-five years.

Since 1946, the APA has set the default rules governing the federal administrative state.4Congress can (and sometimes does) override the APA’s default rules in the organic statutes that govern particular agencies. See 5 U.S.C. § 559 (“Subsequent statute may not be held to supersede or modify [the APA], except to the extent that it does so expressly.”). See generally Stephanie Hoffer & Christopher J. Walker, The Death of Tax Court Exceptionalism, 99 Minn. L. Rev. 221, 243–50 (2014) (detailing the APA’s default judicial review standards and how other statutes can depart from those APA default standards). It dictates how federal agencies regulate and how the federal courts supervise, review, and constrain agency action. The APA also opens space for public participation in the regulatory process, while attempting to close out undue outside influence and lobbying. Notwithstanding the APA’s longevity, Westlaw reports that Congress has only amended the APA sixteen times.5This figure is based on the amendments listed in the Westlaw popular name table for the APA. The amendments are discussed further in Christopher J. Walker, Modernizing the Administrative Procedure Act, 69 Admin. L. Rev. 629, 633–38 (2017). To be sure, Westlaw does not capture every legislative innovation related to the APA and the quasi-constitution of the administrative state.6See id. at 634 n.17 (“Westlaw’s popular name table does not capture every amendment to the Freedom of Information Act and Privacy Act. Nor does it consider other statutory provisions in Title 5 of the U.S. Code that deal with federal agencies yet lie outside of the sections of Title 5 that codify the original APA.” (internal citations omitted)). Other legislative innovations relating to administrative law enacted after the APA include: the Congressional Review Act of 1996, 5 U.S.C. §§ 801–808; the Negotiated Rulemaking Act of 1990, 5 U.S.C §§ 561–570; the Regulatory Flexibility Act of 1980, 5 U.S.C. §§ 601–612; and the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act of 1995, 2 U.S.C. §§ 1501–1571. Yet, in many ways, this figure overstates the legislative reshaping. Over the decades, Congress has only significantly amended the APA four—or at most five—times: the Freedom of Information Act (“FOIA”) in 1966, the Privacy Act in 1974, the Government in the Sunshine Act in 1976, the waiver of sovereign immunity amendment in 1976, and, to a lesser extent, the renaming of administrative law judges (“ALJs”) in 1978. Excluding two FOIA modernizations in 1996 and 2016, there has not been a significant APA legislative reform in more than four decades.7Walker, supra note 5, at 635.

This lack of significant legislative reform does not mean the APA was perfect or fully developed at birth.8The legislative failure to modernize the APA is not for a complete lack of trying. Over the decades, the American Bar Association and the Administrative Conference of the United States have recommended numerous consensus-driven, common-sense reforms. See id. at 638–48 (summarizing efforts). More recently, many Republicans—joined by some Democrats—have introduced a number of bills to modernize the APA. See id. at 648–49. The Portman–Heitkamp Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017, S. 951, 115th Cong., is perhaps the most comprehensive and promising reform proposal in decades. Professor Cass Sunstein, for instance, declared that this legislation “deserves careful attention,” as it is “an intelligent, constructive, complex, imperfect bill.” Cass R. Sunstein, A Regulatory Reform Bill That Everyone Should Like, Bloomberg (June 22, 2017, 8:30 AM), https://perma.cc/7SG9-TW9S. But see Ronald M. Levin, The Regulatory Accountability Act and the Future of APA Revision, 94 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 487, 489 (2019) (“The basic thrust of this essay is that these assessments [of the Regulatory Accountability Act] have been too upbeat. . . . [S]ome of the most consequential items in both bills—proposals that have given them the most propulsive force and political potency—have been decidedly worrisome.”). I have analyzed the Regulatory Accountability Act at length, disclosing there that I worked on the legislation in 2017 as an academic fellow in Senator Orrin Hatch’s office. Walker, supra note 5, at 629 n.*, 648–70. And in August 2020, the U.S. Department of Justice issued a 129-page report, which argues that now is the time for Congress to modernize the APA. See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Modernizing the Administrative Procedure Act (2020),https://perma.cc/CPU4-3RGQ. The APA, as applied by courts and followed by agencies, has evolved considerably over the decades. Indeed, the statutory text bears little resemblance to modern regulatory practice. The Supreme Court and the lower courts—with the D.C. Circuit playing a prominent role—have substantially rewritten the rules of the road. They have done so by grafting onto the APA myriad administrative common law doctrines9See, e.g., Gillian E. Metzger, Embracing Administrative Common Law, 80 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1293, 1295 (2012) (defining and defending “administrative common law” as “administrative law doctrines and requirements that are largely judicially created, as opposed to those specified by Congress, the President, or individual agencies”). But see John F. Duffy, Administrative Common Law in Judicial Review, 77 Tex. L. Rev. 113, 115 (1998) (arguing against administrative common law in the judicial review context). in response to what Professor Gary Lawson has coined “the rise and rise of the administrative state.”10Gary Lawson, The Rise and Rise of the Administrative State, 107 Harv. L. Rev. 1231, 1231 (1994). In 1980, Professor Kenneth Culp Davis observed: “Most administrative law is judge-made law, and most judge-made administrative law is administrative common law.”11Kenneth Culp Davis, Administrative Common Law and the Vermont Yankee Opinion, 1980 Utah L. Rev. 3, 3; cf. Jack M. Beermann, Common Law and Statute Law in Administrative Law, 63 Admin. L. Rev. 1, 4 (2011) (“The most that one can confidently say today is that administrative law contains elements that appear to be highly statutorily focused alongside elements in which courts exercise the discretion of a common law court.”). See generally Aaron L. Nielson, Visualizing Change in Administrative Law, 49 Ga. L. Rev. 757, 776–93 (2015) (detailing how administrative law has changed in various ways since the APA). That is largely still true today. Regulatory practice, moreover, has outgrown the APA in other ways with which even courts have failed to grapple.

This observation is far from novel. Professors Daniel Farber and Anne Joseph O’Connell, for example, explored this phenomenon with respect to the APA and administrative law more generally in their majestic article, The Lost World of Administrative Law.12See generally Daniel A. Farber & Anne Joseph O’Connell, The Lost World of Administrative Law, 92 Tex. L. Rev. 1137 (2014) (examining how the modern administrative state diverges from the foundational assumptions underlying the APA). To be sure, even Professors Farber and O’Connell observed that they “are far from the first to point out aspects of this problem, but the scale of the problem and the need for pragmatic solutions are in need of further exploration.” Id. at 1140. Moreover, Professors Farber and O’Connell’s lost world of administrative law encompasses both “statutes and judicial rulings.” Id. at 1141. In this Article, by contrast, the lost world of the APA separates out the APA’s statutory text from not just modern regulatory practice but also subsequent judicial revisions to the APA. (Indeed, this Article’s title honors their work.) As Farber and O’Connell observed, “there is an increasing mismatch between the suppositions of modern administrative law and the realities of modern regulation. Or to put it another way, administrative law seems to be increasingly based on legal fictions.”13Id. at 1140. Indeed, anyone who has ever taught administrative law struggles to teach through this mismatch between statutory text and regulatory practice.

But this mismatch is even more poignant for those of us who teach Legislation and Regulation—a course that is growing in popularity as a required first-year course in law schools across the nation.14See, e.g., Abbe R. Gluck, The Ripple Effect of “Leg-Reg” on the Study of Legislation & Administrative Law in the Law School Curriculum, 65 J. Legal Educ. 121 (2015) (empirically exploring the rise of Legislation and Regulation and its effect on the upper-level curriculum). As the course title indicates, the first half focuses on legislation—or, more precisely, statutory interpretation.15See, e.g., Dakota S. Rudesill, Christopher J. Walker & Daniel P. Tokaji, A Program in Legislation, 65 J. Legal Educ. 70, 71–78 (2015) (outlining the standard Legislation and Regulation syllabus and its variations). In other words, students spend half a semester exploring how to read and interpret statutory text. These aspiring lawyers learn that some version of textualism is the predominant interpretive theory today.16Cf. Tara Leigh Grove, Which Textualism?, 134 Harv. L. Rev. 265 (2020) (exploring the various strands of textualism). They read dozens of opinions where courts emphasize that the text of a statute generally controls. Most of the hard work of interpretation, they learn, entails resolving ambiguities in statutory text through a variety of interpretive tools, including canons of construction, arguments from statutory structure, context, and purpose, and reference to legislative and other statutory history.

Once the course reaches its halfway point, the attention turns from legislation and statutory interpretation to an introduction to the regulatory state. And this is when the students encounter, for the first time, the enigmatic APA. When I reach this point in the semester, I tell my students that regulatory lawyers would commit malpractice if they just followed the text of the APA. Even seemingly unambiguous text does not mean what it says. Sometimes, courts have interpreted the text of the APA against the backdrop of existing precedent and common law. And other times, courts have added entirely new requirements to various sections of the APA. We then spend a couple of weeks working through a number of examples where the APA’s text—the “lost world”—differs substantially from how federal courts have interpreted—and in some cases rewritten—the APA.

In this contribution to the George Mason Law Review’s APA at 75 Symposium, my ambition is quite modest. This Article seeks to memorialize the lost world of the seventy-five-year-old APA—the mismatches between the statutory text, on the one hand, and judicial interpretation and regulatory practice on the other. In that sense, this Article annotates the key provisions of the APA; it is by no means a comprehensive annotation.17Countless articles, not here cited or discussed, have been written about the APA and its various provisions, including a number of prior commemorative symposia. See, e.g., Administrative Law Symposium, 72 Va. L. Rev. 215, 215–492 (1986) (focusing on developments in the APA at its fortieth anniversary); Symposium on the 50th Anniversary of the APA, 10 Admin. L.J. Am. U. 1, 1–249 (1996). In the field of administrative law, we are long overdue for a desktop annotated treatise on the APA. Instead, this Article focuses on the most substantial mismatches; it is by no means a comprehensive analysis of those mismatches. Indeed, as this Article will document, others have written extensively on some of the mismatches. In that sense, this Article is both a limited annotation and a bounded literature review of the mismatches in the APA at seventy-five.

A brief note on methodology: This Article is admittedly narrow in scope in that it is a textualist survey of the APA. It largely leaves to one side the forceful arguments by Professors Gillian Metzger and Peter Strauss, among others, that the APA has not and should not remain static, but it instead has evolved and should evolve through administrative common lawmaking and in response to changes in the regulatory landscape.18See, e.g., Metzger, supra note 9, at 1297 (“The argument for embracing administrative common law goes beyond establishing that it is ubiquitous, inevitable, and legitimate. Openly acknowledging the role that judicial lawmaking plays in administrative contexts is critical to clarifying and improving administrative law.”); Peter L. Strauss, Statutes That Are Not Static—The Case of the APA, 14 J. Contemp. Legal Issues 767, 768–69 (2005) (similar); see also Adrian Vermeule, Rules, Commands, and Principles in the Administrative State, 130 Yale L.J. F. 356, 358 (2021) (“Whatever the details, administrative law has not come to be dominated by ad hoc agency commands, as theorists of the Progressive Era and afterwards anticipated. Rather administrative law features a thick ecology of legal principles that jostle, compete, and develop over time.”). Put differently, this Article does not attempt to engage with the important scholarship on dynamic statutory interpretation that Professor Bill Eskridge ushered in some three decades ago.19See generally William N. Eskridge, Jr., Dynamic Statutory Interpretation (1994); Eskridge & Ferejohn, supra note 3. Indeed, this Article is more of a textualist, rather than originalist, project, as it compares the statutory text to current doctrine and regulatory doctrine. It does not endeavor to carry out the important yet daunting task of examining the historical, original meaning of the terms Congress included in the APA.20Cf. Emily S. Bremer, The Rediscovered Stages of Agency Adjudication (Mar. 5, 2021) (unpublished manuscript), https://perma.cc/GVG3-QCVX (exploring the original understanding of administrative adjudication under the APA).

Nor does this Article aim to take a definitive normative position on these mismatches, much less consider the strong pull of statutory stare decisis against any potential judicial reforms.21See, e.g., Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia & Christopher J. Walker, The Case Against Chevron Deference in Immigration Adjudication, 70 Duke L.J. 1197, 1236 n.204 (2021) (“Although scholars and judges may well reasonably disagree about the pull of statutory stare decisis in this context, one of us (Walker) is not convinced that overturning this statutory precedent [of Chevron deference] would be consistent with the doctrine of stare decisis.”). Many, if not most, of these mismatches between statutory text and current doctrine are welcome developments as a matter of administrative process and policy. Many should be noncontroversial provisions in any legislative modernization of the APA. Instead, the goal here is much more modest. Through presenting this annotation and literature review, this Article hopes to survey areas for further scholarly attention, potential legislative reform, and perhaps judicial engagement.

This Article proceeds as follows: Part I annotates the APA’s key “Administrative Procedure” provisions, and then Part II turns to the “Judicial Review” provisions. Part III briefly surveys the president’s role in the regulatory state that largely is absent from the APA’s text yet omnipresent in administrative governance today.

I. Administrative Procedure Under the APA

With respect to administrative procedure, the APA establishes detailed procedures for the two core means of agency action—rulemaking and adjudication—while recognizing that other statutes may provide for different forms of and procedures for agency action.22See 5 U.S.C. § 553 (rulemaking provisions); id. § 554 (adjudication provisions); id.§ 559 (recognizing that other statutes can provide additional or different agency procedures).

The conventional account is that the Supreme Court has rebuffed judicial efforts to graft on additional agency procedures not required by statute. To some extent that is true. Most famously, in Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. Natural Resource Defense Council, Inc.,23435 U.S. 519 (1978). the Court held that “[a]gencies are free to grant additional procedural rights in the exercise of their discretion, but reviewing courts are generally not free to impose them if the agencies have not chosen to grant them.”24Id. at 524; see also Pension Ben. Guar. Corp. v. LTV Corp., 496 U.S. 633, 655 (1990) (applying Vermont Yankee to the agency adjudication context). See generally Gillian E. Metzger, The Story of Vermont Yankee, in Administrative Law Stories 124, 149–50 (Peter L. Strauss ed., 2006) (observing that the Vermont Yankee “opinion is a masterpiece of obfuscation”); Scalia, supra note 3, at 356 (similar). More recently, in Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Ass’n,25575 U.S. 92 (2015). the Court rejected another D.C. Circuit administrative common law doctrine—the requirement of rulemaking to reverse certain agency guidance from Paralyzed Veterans of America v. D.C. Arena L.P.26117 F.3d 579, 586 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (“Once an agency gives its regulation an interpretation, it can only change that interpretation as it would formally modify the regulation itself: through the process of notice and comment rulemaking.”), abrogated by Perez, 575 U.S. at 107.—holding that it “improperly imposes on agencies an obligation beyond the ‘maximum procedural requirements’ specified in the APA.”27Perez, 575 U.S. at 100 (quoting Vermont Yankee, 435 U.S. at 524). See generally Kathryn E. Kovacs, Pixelating Administrative Common Law in Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Association, 125 Yale L.J. F. 31 (2015) (examining the Perez decision and arguing for the Court to step back and address the overarching problems with administrative common law).

But the conventional account is incomplete. With respect to both rulemaking and adjudication, today’s administrative state—and the APA that governs it—looks much different from what the framers of the APA likely envisioned. Or, perhaps more precisely and modestly, it departs substantially from the statutory text. Consider rulemaking and adjudication in turn.

A. Rulemaking: From Formal to Informal to More-Formal Informal to Subregulatory Guidance

The APA defines “rule” broadly to include:

[T]he whole or a part of an agency statement of general or particular applicability and future effect designed to implement, interpret, or prescribe law or policy or describing the organization, procedure, or practice requirements of an agency and includes the approval or prescription for the future of rates, wages, corporate or financial structures or reorganizations thereof, prices, facilities, appliances, services or allowances therefor or of valuations, costs, or accounting, or practices bearing on any of the foregoing.285 U.S.C. § 551(4).

The main provisions for agency rulemaking under the APA can be found in section 553. The terms are plain on their face. With some statutory exceptions,29These rulemaking procedures are not required under the APA when the rule involves “(1) a military or foreign affairs function of the United States; or (2) a matter relating to agency management or personnel or to public property, loans, grants, benefits, or contracts.” Id. § 553(a). Similarly the APA’s notice-and-comment process is not required when it comes “to interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice” or “when the agency for good cause finds (and incorporates the finding and a brief statement of reasons therefor in the rules issued) that notice and public procedure thereon are impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.” Id. § 553(b)(A), (b)(B). Parts I.A.3 and I.A.2, respectively, return to these latter two exceptions. section 553 requires agencies to engage in three stages for rulemaking.

First, the agency must provide a “general notice of proposed rulemaking” that discloses “(1) a statement of the time, place, and nature of public rule making proceedings; (2) reference to the legal authority under which the rule is proposed; and (3) either the terms or substance of the proposed rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved.”30Id.§ 553(b).

Second, the agency must facilitate public participation. This entails allowing “interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making through submission of written data, views, or arguments with or without opportunity for oral presentation.”31Id. § 553(c). Importantly, the APA requires more formal procedures “[w]hen rules are required by statute to be made on the record after an opportunity for an agency hearing.”32Id. In those circumstances, sections 556 and 557 apply, which require a trial-like hearing before the agency head, a subset of members on a multi-member agency commission or board, or an ALJ. This formal hearing resembles civil litigation in federal court, with interested parties having the right to put on witnesses, introduce evidence, cross-examine witnesses, and the like.33See id. §§ 556–57. (Part I.B.1 returns to these formal procedures, as they similarly apply to formal adjudication under the APA.)

Third, after the agency has heard from the public, the agency must issue a final rule that “incorporate[s] in the rules adopted a concise general statement of their basis and purpose.”345 U.S.C. § 553(c). For formal rulemaking where sections 556 and 557 apply, the agency must issue a more detailed statement as part of the final rule, which includes “(A) findings and conclusions, and the reasons or basis therefor, on all the material issues of fact, law, or discretion presented on the record; and (B) the appropriate rule, order, sanction, relief, or denial thereof.”35Id. § 557(c)(A)–(B).

The statutory text seems straightforward. But its application today is not. There are at least three chapters in the rulemaking story.

1. From Formal to Informal Rulemaking

Students of administrative law are no doubt quite familiar with the first chapter in this story—the death of formal rulemaking and the rise of informal, notice-and-comment rulemaking. Few professors who teach Administrative Law (or Legislation and Regulation) would fail to assign the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Florida East Coast Railway Co.36410 U.S. 224 (1973).

Based on the text of the APA, one would reasonably conclude that any time the agency’s organic statute requires a hearing as part of the rulemaking, the APA’s more formal trial-like proceedings detailed in sections 556 and 557 would apply. But in Florida East Coast Railway, the Court rejected that conclusion. It held that the APA’s formal provisions do not apply just because the agency’s organic statute requires a “hearing”; the organic statute must require both “on the record” and “after . . . an agency hearing.”37Id. at 237. The Court noted that these magic words might not always be required, such that “other statutory language having the same meaning could trigger the provisions of §§ 556 and 557 in rulemaking proceedings.” Id. at 238. That wrinkle has not made a difference since. Few, if any, statutes contain such language. As Professor Aaron Nielson concluded in his extensive defense of formal rulemaking, Florida East Coast Railway—“a case which has won little praise for its reasoning but whose policy outcome has been celebrated”—“largely put an end to formal rulemaking.”38Aaron L. Nielson, In Defense of Formal Rulemaking, 75 Ohio St. L.J. 237, 247 (2014). See generally Michael P. Healy, Florida East Coast Railway and the Structure of Administrative Law, 58 Admin. L. Rev. 1039, 1040 (2006) (exploring what the decision means beyond its core holding). As Professor Barnett explores by examining the Justices’ papers, the Court’s prior decision in United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Steel Corp., 406 U.S. 742 (1972), “rendered Florida East Coast Railway a fait accompli, stifling the limited persuasive force of the parties’ briefing and Justice Douglas’s notoriously hard-to-follow dissent.” Kent Barnett, How the Supreme Court Derailed Formal Rulemaking, 85 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. Arguendo 1, 3, 4 (2017) (noting that “[t]ogether, Allegheny-Ludlum and Florida East Coast Railway . . . all but ended formal rulemaking in the federal administrative state”). Cf. Stephen F. Williams, “Hybrid Rulemaking” under the Administrative Procedure Act: A Legal and Empirical Analysis, 42 U. Chi. L. Rev. 401, 402 (1974) (detailing how, “with only a little help from Congress, the courts seem to have created a procedural category that might be termed ‘hybrid rulemaking’ or ‘notice-and-comment-plus’”).

Florida East Coast Railway made an additional contribution to how APA rulemaking operates. It held that when an organic statute requires a “hearing,” that “does not necessarily embrace either the right to present evidence orally and to cross-examine opposing witnesses, or the right to present oral argument to the agency’s decisionmaker.”39Fla. E. Coast Ry., 410 U.S. at 240. A “paper” hearing is perfectly appropriate for informal, notice-and-comment rulemaking.40Indeed, the Court held that, even when the APA’s formal hearing requirements apply, “a specific statutory mandate that the proceedings take place on the record after hearing may be satisfied in some circumstances by evidentiary submission in written form only.” Id. at 241.

In sum, Florida East Coast Railway can be viewed as the antithesis of the Vermont Yankee problem. The Court did not graft procedural requirements onto the APA that lack any textual support. Instead, the Florida East Coast RailwayCourt, for all intents and purposes, deleted from the APA the formal hearing requirements for rulemaking. As outlined in Part I.A.2, over the next decades, the Court arguably rewrote the APA to reintroduce more-formal rulemaking procedures.

2. From Informal to More-Formal Rulemaking

With the formal rulemaking provisions essentially excised from the APA, what remains should be a straightforward notice-and-comment rulemaking process. The agency must merely provide a general statement of proposed rulemaking, allow the public to comment on the proposed rule, and then issue a final rule that includes a concise statement of basis and purpose.

Not so fast. In what Professor Richard Stewart coined as administrative law’s Reformation, federal courts responded to concerns about unbounded agency discretion by further proceduralizing (or formalizing) notice-and-comment rulemaking.41See Richard B. Stewart, The Reformation of American Administrative Law, 88 Harv. L. Rev. 1667, 1669–70 (1975). Four such evolutions bear mention here.

First, at the public notice stage, much more is required than just a “[g]eneral notice” of “either the terms or substance of the proposed rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved.”425 U.S.C. § 553(b)(3). Courts have expanded on this statutory provision to require a detailed explanation of the proposed rule and a disclosure of the underlying rationales and supporting data. The most prominent administrative common law here is the Portland Cementdoctrine. As the D.C. Circuit explained in Portland Cement Ass’n v. Ruckelshaus,43486 F.2d 375 (D.C. Cir. 1973). “[i]n order that rule-making proceedings to determine standards be conducted in orderly fashion, information should generally be disclosed as to the basis of a proposed rule at the time of issuance.”44Id. at 394. “If this [initial disclosure] is not feasible,” the court further explained, “as in case of statutory time constraints, information that is material to the subject at hand should be disclosed as it becomes available, and comments received, even though subsequent to issuance of the rule—with court authorization, where necessary.”45Id.

This doctrine is not without controversy. As then-Judge Kavanaugh argued, the Portland Cement disclosure doctrine “stands on a shaky legal foundation (even though it may make sense as a policy matter in some cases)” because it “cannot be squared with the text of § 553 of the APA.”46Am. Radio Relay League, Inc. v. FCC, 524 F.3d 227, 246 (D.C. Cir. 2008) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring in part, concurring in the judgment in part, and dissenting in part); see also Jack M. Beermann & Gary Lawson, Reprocessing Vermont Yankee, 75 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 856, 894 (2007) (arguing that Portland Cement is “a violation of the basic principle of Vermont Yankee that Congress and the agencies, but not the courts, have the power to decide on proper agency procedures”); accord Kathryn E. Kovacs, Rules About Rulemaking and the Rise of the Unitary Executive, 70 Admin. L. Rev. 515, 537–39 (2018). On the other hand, as Professor Strauss has argued, perhaps this more robust notice requirement is justified by Congress’s modernization of the APA through FOIA.47Strauss, supra note 18, at 798 (“Whatever rulemaking ‘notice’ may have entailed to the drafters of 1946, in the changed rulemaking environment of the 1960s FOIA both invited its reshaping and served to give the judge confidence that her reshaping better fit the general framework of contemporary law. The Congresses that adopted FOIA and its amendments were of course not the legislators of 1946; but they were legislators crafting a considerably more contemporary set of instructions to the judiciary, also relying on the judges’ faithfulness as servants of the law as they understand it to be.”).

Second, informal rulemaking—in contrast to formal rulemaking—is not “on the record,” and thus section 553 arguably does not require the agency to maintain a publicly available administrative record for the proceeding.48See, e.g., Kovacs, supra note 46, at 533–37. Yet the Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that an agency’s action must be judged based on the “administrative record made.”49Vt. Yankee Nuclear Power Corp. v. NRDC, 435 U.S. 519, 549 (1978) (first citing Camp v. Pitts, 411 U.S. 138, 143 (1973); and then citing SEC v. Chenery Corp., 318 U.S. 80 (1943)). This administrative record requirement finds some support in the APA’s judicial review provisions. In particular, the APA instructs that “the court shall review the whole record or those parts of it cited by a party.” 5 U.S.C. § 706. This administrative record requirement, along with Portland Cement and related doctrines, has led to substantial investments by federal agencies to create online databases to facilitate public access to the proposed rulemaking, accompanying data and studies, and the public comments lodged. The General Services Administration has taken over many of these functions with the launch of regulations.gov.50For more on the General Services Administration’s eRulemaking Initiative, see U.S. GSA, The Rulemaking Initiative (Feb. 15, 2020), https://perma.cc/B9CH-NUB5.

Third, it would be error to read the APA as providing that the final rule need only include “a concise general statement of [its] basis and purpose.”515 U.S.C. § 553(c) (emphasis added). Instead, final rules today include voluminous preambles that are anything but concise or general. As a result, there is a whole subfield in administrative law, pioneered by Professor Kevin Stack, that explores the implications of these preambles for regulatory interpretation and administration governance.52See, e.g., Kevin M. Stack, Interpreting Regulations, 111 Mich. L. Rev. 355 (2012); Kevin M. Stack, Preambles as Guidance, 84 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1252 (2016); see also Jennifer Nou, Regulatory Textualism, 65 Duke L.J. 81 (2015); Christopher J. Walker, Inside Regulatory Interpretation: A Research Note, 114 Mich. L. Rev. First Impressions 61 (2015). Again, federal courts seem to drive this divergence between statutory text and regulatory practice. The Supreme Court has interpreted the APA to require that “[a]n agency must consider and respond to significant comments received during the period for public comment.”53Perez v. Mortg. Bankers Ass’n, 575 U.S. 92, 96 (2015) (citing Citizens to Pres. Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 416 (1971)). This APA evolution may make a lot of policy sense, especially in light of the shift in the importance of health, safety, and environmental regulation in the 1960s and 1970s. But it makes little textual sense. After all, the APA requires a “concise” and “general” articulation of the final rule’s “basis and purpose.”54See, e.g., Kovacs, supra note 46, at 542–44.

Fourth, just as federal courts have required agencies to respond to significant comments, they have required final rules to be a “logical outgrowth” of proposed rules.55See, e.g., Nat’l Black Media Coal. v. FCC, 791 F.2d 1016, 1022 (2d Cir. 1986); United Steelworkers v. Marshall, 647 F.2d 1189, 1221 (D.C. Cir. 1980); S. Terminal Corp. v. EPA, 504 F.2d 646, 659 (1st Cir. 1974); see also Phillip M. Kannan, The Logical Outgrowth Doctrine in Rulemaking, 48 Admin. L. Rev. 213 (1996). In other words, as the D.C. Circuit has framed the doctrine, “[w]here the change between proposed and final rule is important, the question for the court is whether the final rule is a ‘logical outgrowth’ of the rulemaking proceeding.”56Marshall, 647 F.2d at 1221. Under this logical outgrowth doctrine, the Supreme Court has explained that “[t]he object, in short, is one of fair notice.”57Long Island Care at Home, Ltd. v. Coke, 551 U.S. 158, 174 (2007). Nothing in the APA expressly requires this. Indeed, the APA instructs agencies to provide a “[g]eneral notice of proposed rule making” that discloses “the legal authority under which the rule is proposed” and “either the terms or substance of the proposed rule or a description of the subjects and issues involved.”585 U.S.C. § 553(b)(2)–(3) (emphasis added).

By highlighting these mismatches between statutory text and administrative common law, this Article does not intend to suggest that these judicial innovations make for bad policy. Elsewhere I have praised them as common-sense, should-be bipartisan reforms that Congress should include in any modernization of the APA.59See Walker, supra note 5, at 638–48. And some of these judicial innovations may well be consistent with the spirit of subsequent congresses’ modernization of the APA through FOIA and the Sunshine in Government Act.60See, e.g., Strauss, supra note 18, at 789–90. In many ways, the federal courts have developed administrative common law to reintroduce a more-formal rulemaking process that the Supreme Court essentially killed in Florida East Coast Railway.

One final development merits a brief mention. The text of the APA allows federal agencies to promulgate a rule without first engaging in the notice-and-comment process when they can demonstrate “good cause”—i.e., when “notice and public procedure thereon are impracticable, unnecessary, or contrary to the public interest.”615 U.S.C. § 553(b)(3)(B). Agencies have increasingly turned to—and perhaps abused—this “good cause” exception to bypass the notice-and-comment process. In 2012, for example, the Government Accountability Office found that federal agencies from 2003 through 2010 skipped the notice-and-comment process for thirty-five percent of “major” rules and forty-four percent of nonmajor rules.62U.S. Gov’t Accountability Office, GAO-13-21, Federal Rulemaking: Agencies Could Take Additional Steps to Respond to Public Comments 3 n.6, 8, 36 (2012). Agencies engaged in post-promulgation notice-and-comment processes for sixty-five percent of those major rules issued without notice and comment.63See id.at 24–25.

Professor Kristin Hickman and Mark Thomson have explored this rise of interim final rulemaking and how, in practice, it can be inconsistent with the APA.64Kristin Hickman & Mark Thomson, Open Minds and Harmless Errors: Judicial Review of Post-Promulgation Notice and Comment, 101 Cornell L. Rev. 261, 285–305 (2016). In light of those concerns, they have argued for a strong judicial presumption against the validity of postpromulgation notice and comment.65Id. at 311 (arguing that “a strong presumption against the validity of postpromulgation notice and comment best respects the balance between an express statutory command for prepromulgation notice and comment and a particularized harmless error rule.”). I have similarly endorsed such a judicial standard, going perhaps further to argue that if a court finds there was no good cause to skip notice and comment, perhaps the error should be deemed structural such that no showing of prejudice is required.66Christopher J. Walker, Against Remedial Restraint in Administrative Law, 117 Colum. L. Rev. Online 106, 118–19, 119 n.75 (2017).

3. From Rulemaking to Subregulatory Guidance

In recent years, more scholarly and policy attention has been paid to agencies’ purported shift from rulemaking to agency guidance as a regulatory tool.67I say “purported shift” because it is not at all clear that agencies use guidance more today than they did in the early decades after the APA’s birth or how agencies have shifted from rulemaking to guidance. Much more empirical work is needed to substantiate this claim. See generally Nicholas R. Parrillo, Federal Agency Guidance and the Power to Bind: An Empirical Study of Agencies and Industries, 36 Yale J. on Regul. 165 (2019) (detailing current debates on agency guidance and presenting findings of extensive empirical study on agencies’ use of subregulatory guidance). To be sure, the APA originally contemplated the use of agency guidance by expressly exempting “interpretative rules, general statements of policy, [and] rules of agency organization, procedure, or practice” from the APA’s rulemaking provisions.685 U.S.C. § 553(b)(A). But the APA otherwise provides little guidance on how agencies should use guidance as a regulatory tool. As Professor Ron Levin has detailed, “[q]uestions pertaining to the application of this exemption may constitute the single most frequently litigated and important issue of rulemaking procedure in the federal courts today.”69Ronald M. Levin, Rulemaking and the Guidance Exemption, 70 Admin. L. Rev. 263, 263 (2018).

The conventional understanding is that agency guidance does not have the force of law, and thus is not judicially reviewable absent the agency’s application of that guidance in enforcement or adjudication. Whether agency guidance is actually nonbinding on regulated parties—formally or at least functionally—is subject to debate.70See Parrillo, supranote 67, at 184–231 (detailing incentives of regulated entities to comply with agency guidance). Last year, for example, the Justice Department issued an interim final rule that sets forth rules and procedures for creating agency guidance documents, including that “[g]uidance documents may not be used as a substitute for regulation and may not be used to impose new standards of conduct on persons outside the Executive Branch.”7128 C.F.R. § 50.27(c)(1)(i) (2020).

What is clear, however, is that subregulatory guidance plays a critical role in modern administrative governance. Yet although the statutory text contemplates subregulatory guidance’s existence, the APA arguably does not provide sufficient instructions on its appropriate use.

B. Adjudication: The Predominance of Adjudication Between Formal and Informal

If asked what the predominant form of administrative procedure under the APA is today, most scholars and students of administrative law would say notice-and-comment rulemaking. But it is important to realize that, in 1946, the founders of the APA were primarily concerned with administrative adjudication.72See Shepherd, supra note 2, at 1575–77 (discussing the APA’s founding). Indeed, the shift from adjudication to rulemaking did not occur until the 1960s and 1970s—perhaps viewed as a more democratically legitimate mode of administration.73See Martin Shapiro, APA: Past, Present, Future, 72 Va. L. Rev. 447, 456 (1986); accord Farber & O’Connell, supra note 12, at 1143–44.

Last year, in my introduction to the Duke Law Journal Charting the New Landscape of Administrative Adjudication Symposium, I surveyed how, in recent years and in terms of both scholarly and judicial attention, the tides have started to turn back to adjudication.74Christopher J. Walker, Charting the New Landscape of Administrative Adjudication, 69 Duke L.J. 1687, 1689–90 (2020). Here, this Article divides the story of agency adjudication into three chapters, drawing substantially from Professor Melissa Wasserman and my more extended account.75See Christopher J. Walker & Melissa F. Wasserman, The New World of Agency Adjudication, 107 Calif. L. Rev. 141, 148–73 (2019). At the outset, it is worth noting that the adjudication and rulemaking stories differ in theme and main takeaways. The evolution of rulemaking demonstrates inconsistency between the APA’s text and modern administrative law doctrine and practice. The evolutionary story of adjudication, by contrast, is more about how the new world of agency adjudication exists largely outside of the APA. Put differently, administrative adjudication has largely outgrown the APA, and Congress has done little to remedy that.

1. The Lost World of APA Formal Adjudication

As it does with rulemaking, the APA divides adjudication into two broad categories: formal and informal. Or more precisely, section 554 sets forth the procedures “in every case of adjudication required by statute to be determined on the record after opportunity for an agency hearing.”765 U.S.C. § 554(a). Section 554 includes a number of exceptions, including where a statute requires a trial de novo, the “agency is acting as an agency for a court,” or the matter deals with “inspections test, and election,” “military or foreign affairs functions,” or “the certification of worker representations.” Id. For those section 554 adjudications, the formal hearing provisions of section 556 and 557 apply, discussed in Part I.A.1.77See id. §§ 554, 556–57. The APA has little to say about what has been termed “informal adjudication”—that residual category that encompasses any agency adjudication not subject to section 554.78Section 555, dealing with “ancillary matters,” provides for some procedural protections that apply to informal adjudications. Id. § 555. Section 558 addresses the imposition of sanctions and the handling of licenses. Id. § 558. Indeed, this residual category opaquely encompasses any agency action—termed “order”—that is not the product of formal adjudication or any type of rulemaking.79Id. § 551(7) (defining adjudication as the “agency process for the formulation of an order”); see also id.§ 551(6) (defining order as “the whole or a part of a final disposition, whether affirmative, negative, injunctive, or declaratory in form, of an agency in a matter other than rule making but including licensing”).

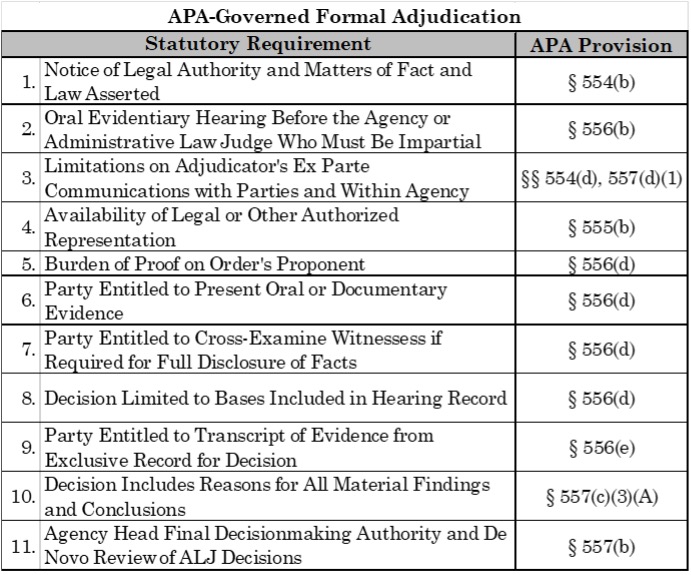

For APA-governed formal adjudications—what Professor Wasserman and I have coined the “lost world of agency adjudication”—the APA requires, subject to modification in the agency’s organic statute, a number of trial-like procedures that one would find in a federal court bench trial. The following table summarizes the key statutory requirements for APA-governed formal adjudication.80This table draws from 1 Richard J. Pierce, Administrative Law Treatise 703 (2010), and is reproduced from Walker & Wasserman, supra note 75, at 149 tbl.1.

Table 1

The paradigmatic APA-governed formal adjudication involves an evidentiary hearing before an ALJ. The parties are entitled to oral arguments, rebuttal, and cross-examination of witnesses. The ALJ presiding over the hearing is functionally equivalent to a trial judge in a bench trial. The ALJ is the principal factfinder and initial decision maker, and the APA empowers ALJs to “regulate the course of the hearing.”815 U.S.C. § 557(c)(A)–(B). Although ALJs do not have life tenure like federal judges, Congress has limited agency control over the selection, retention, and removal of ALJs, such that they enjoy strong decisional independence.82See 5 U.S.C. §§ 554(d)(2), 3105, 5372; see also Harold H. Bruff, Specialized Courts in Administrative Law, 43 Admin. L. Rev. 329, 346 (1991); Jeffrey S. Lubbers, Federal Administrative Law Judges: A Focus on Our Invisible Judiciary, 33 Admin. L. Rev. 109, 112–20 (1981); Paul R. Verkuil, Reflections Upon the Federal Administrative Judiciary, 39 UCLA L. Rev. 1341, 1344 (1992). A party dissatisfied with an ALJ’s initial decision may seek further agency appellate review (and then judicial review), and the agency head generally has final decision-making authority.83See 5 U.S.C.§ 557(b) (providing that, in cases where “the agency did not preside at the reception of the evidence, the presiding employee . . . shall initially decide the case,” and that initial “decision then becomes the decision of the agency without further proceedings unless there is an appeal to, or review on motion of, the agency within time provided by rule”); see also Christopher J. Walker & Matthew Lee Wiener, Final Report for the Administrative Conference of the United States: Agency Appellate Systems (2020); Russell L. Weaver, Appellate Review in Executive Departments and Agencies, 48 Admin. L. Rev. 251 (1996).

2. The New World of Formal-Like Adjudication

As Professor Wasserman and I have chronicled, the vast majority of agency adjudications are not paradigmatic “formal” adjudications as set forth in the APA. That is the lost world. The new world of agency adjudication involves a variety of less-independent administrative judges, hearing officers, and other agency personnel adjudicating disputes where statute or regulation requires an administrative hearing. In the modern regulatory state, these administrative judges outnumber ALJs at least fivefold.84See Kent Barnett & Russell Weaver, Non-ALJ Adjudicators in Federal Agencies: Status, Selection, Oversight, and Removal, 53 Ga. L. Rev. 1, 5 (2019). As Professor Michael Asimow has observed, the APA “fails to regulate in any significant way the vast and rapidly increasing number of more or less formal evidentiary adjudicatory hearings required by federal statutes that are not conducted by ALJs and yet are functionally indistinguishable from the hearings that are conducted by ALJs.”85Michael Asimow, The Spreading Umbrella: Extending the APA’s Adjudication Provisions to All Evidentiary Hearings Required by Statute, 56 Admin. L. Rev. 1003, 1020 (2004).

In this new world, it turns out that there is great diversity in procedures by which federal agencies adjudicate—some set by the respective agency’s organic statute but most set by regulation or subregulatory guidance. Professors Michael Asimow, Kent Barnett, and Emily Bremer, among others, have done critical work to map out the great diversity of non-APA formal-like adjudicative systems in the modern administrative judiciary and to identify current procedural deficiencies and structural flaws.86See, e.g., Michael Asimow, Federal Administrative Adjudication Outside the Administrative Procedure Act (2019); Asimow, supra note 85; Kent Barnett, Against Administrative Judges, 49 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 1643 (2016); Kent Barnett, Regulating Impartiality in Agency Adjudication, 69 Duke L.J. 1695 (2020); Barnett & Weaver, supra note 84; Emily S. Bremer, The Exceptionalism Norm in Administrative Adjudication, 2019 Wis. L. Rev. 1351. As Professor Bremer has underscored, it is not a new world just because the vast majority of adjudications take place outside of the formal provisions of the APA. There is also an APA-departing norm of “exceptionalism” in the new world of agency adjudication—“a presumption in favor of procedural specialization and against uniform, cross-cutting procedural requirements.”87Emily S. Bremer, Reckoning with Adjudication’s Exceptionalism Norm, 69 Duke L.J. 1749, 1752 (2020).

In other words, the APA tells us very little about the procedures and practices for the vast majority of formal-like adjudications in the modern administrative state. We must look to the respective agencies’ governing statutes, regulations, and guidance.

3. The Unchartered Frontier of Informal Adjudication

The relatively unchartered frontier of informal adjudication merits a brief note. Administrative law scholars have started to pay much more attention to formal-like agency adjudication that is not governed by the APA but where a statute or regulation requires an administrative hearing. As a field, however, we have barely begun to explore in any systematic manner the terrain of informal adjudication where an agency official adjudicates without holding a hearing.

This category of regulatory action is similarly vast and varied—ranging from tens of thousands of IRS tax adjudications a year88See, e.g., Hoffer & Walker, supra note 4, at 276–89. to hundreds of thousands of “shadow removals” of noncitizens from the United States each year.89Jennifer Lee Koh, Removal in the Shadows of Immigration Court, 90 S. Cal. L. Rev. 181, 183 (2017); see also Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia, Banned: Immigration Enforcement in the Time of Trump 79–97 (2019). To be sure, this unchartered terrain is not entirely new. At the APA’s enactment, the vast majority of administrative actions likely fell into this category.90In a groundbreaking new article, Professor Bremer argues that, as an original matter, the APA’s formal and informal categories for adjudication are misunderstood: When the APA was adopted, informal and formal adjudication were not viewed as alternative modes, but rather as consecutive stages. Agencies used informal techniques during the initial stages of the adjudicative process. In the vast majority of cases, the agency determination generated through the initial, informal stage was sufficient to bring the matter to a close. Bremer, supra note 20, at *3. But the category remains underexplored in the literature. And the APA says almost nothing about the administrative procedures for these informal adjudications.

II. Judicial Review Under the APA

With respect to the APA’s judicial review provisions, extensive administrative common law remains on the books. Nearly two decades ago, Professor John Duffy penned an influential, 100-page article on administrative common law in judicial review.91See generally Duffy, supra note 9. Here, this Article merely surveys some of these doctrines, divided into three categories: threshold judicial review doctrines, standards of review, and judicial remedies.

A. Threshold Review Doctrines: Exhaustion, Ripeness, Standing, and the Presumption of Reviewability

The APA’s judicial review provisions apply broadly whenever Congress has made a particular agency action “reviewable by statute” or the action is “final agency action for which there is no other adequate remedy in a court.”925 U.S.C. § 704. The APA precludes judicial review only if another statute expressly does so or if “agency action is committed to agency discretion by law.”93Id. § 701(a)(2); see id. § 559 (“Subsequent statute may not be held to supersede or modify [the APA], except to the extent that it does so expressly.”). Outside of those two exceptions, the APA provides for judicial review for any “person suffering legal wrong because of agency action, or adversely affected or aggrieved by agency action within the meaning of a relevant statute.”94Id. § 702.

Despite these relatively clear guidelines about who can seek judicial review under the APA as well as when and for what, courts have muddied the waters. As Professor Duffy explained, until the Supreme Court’s 1993 decision in Darby v. Cisneros,95509 U.S. 137 (1993). courts had grafted onto the APA an administrative exhaustion requirement—the rule that a party must exhaust all administrative remedies before seeking judicial review.96See Duffy, supra note 9, at 156–59. The Darby Court rejected any such exhaustion requirement, holding that the APA only requires a “final agency action.”97See Darby, 509 U.S. at 144–47.

Although it eliminated the exhaustion requirement, the Court has grafted onto the APA two other atextual threshold doctrines that may limit judicial review: prudential ripeness and prudential standing. In Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner,98387 U.S. 136 (1967), abrogated on other grounds by Califano v. Sanders, 430 U.S. 99 (1977). the Court recognized a prudential ripeness doctrine for preenforcement review of agency action, which instructs courts “to evaluate both the fitness of the issues for judicial decision and the hardship to the parties of withholding court consideration.”99Abbott Lab’ys, 387 U.S. at 149. Professor Duffy argues at length that this administrative common law should be eliminated as inconsistent with the APA’s text.100See Duffy, supra note 9, at 162–81; accord Kovacs, supra note 3, at 1211 (expressing concern about the “prudential ripeness doctrine, which conflicts with the APA’s promise of judicial review to any person who suffers a legal wrong and challenges final agency action”). More recently, the Court has perhaps hinted that prudential ripeness may not be long for this world.101See Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, 573 U.S. 149, 167 (2014) (“In any event, we need not resolve the continuing vitality of the prudential ripeness doctrine in this case because the ‘fitness’ and ‘hardship’ factors are easily satisfied here.”).

In Ass’n of Data Processing Service Organizations, Inc. v. Camp,102397 U.S. 150 (1970). the Court held that prudential standing “concerns, apart from the [Article III jurisdictional] ‘case’ or ‘controversy’ test, the question whether the interest sought to be protected by the complainant is arguably within the zone of interests to be protected or regulated by the statute or constitutional guarantee in question.”103Id. at 153 (emphasis added). It interpreted the APA’s zone of interest—any person “aggrieved by agency action within the meaning of a relevant statute”1045 U.S.C. § 702.—to “reflect ‘aesthetic, conservational, and recreational’ as well as economic values.”105Data Processing, 397 U.S. at 154.

On its face, this zone-of-interest test for prudential standing seems quite demanding in ways that depart from the APA’s text.106See, e.g., Joseph Vining, Legal Identity: The Coming of Age of Public Law 39 (1978) (declaring Data Processing “a shift in the axioms of legal thinking”); Lee A. Albert, Standing to Challenge Administrative Action: An Inadequate Surrogate for Claim for Relief, 83 Yale L.J. 425, 476, 495 (1974) (criticizing Data Processing as an “inappropriate notion of access standing” that preceded “focusing upon the claims for relief”); William A. Fletcher, The Structure of Standing, 98 Yale L.J. 221, 236 n.76 (1988) (“Under Data Processing’s view of the matter, whether plaintiff actually has the right to sue is a question of law on ‘the merits.’”). In practice, however, the Court has emphasized that this prudential standing requirement “is not meant to be especially demanding.”107Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi Indians v. Patchak, 567 U.S. 209, 225 (2012) (quoting Clarke v. Sec. Indus. Ass’n, 479 U.S. 388, 399 (1987)). The Court has explained:

We apply the test in keeping with Congress’s evident intent when enacting the APA to make agency action presumptively reviewable. We do not require any indication of congressional purpose to benefit the would-be plaintiff. And we have always conspicuously included the word “arguably” in the test to indicate that the benefit of any doubt goes to the plaintiff. The test forecloses suit only when a plaintiff’s interests are so marginally related to or inconsistent with the purposes implicit in the statute that it cannot reasonably be assumed that Congress intended to permit the suit.108Id. at 225 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted).

Recently, Professor Caleb Nelson has challenged this reading of Data Processing and of the APA more generally, arguing that “[t]he Supreme Court has never made a considered decision that when an agency is behaving unlawfully, the APA confers the same remedial rights upon plaintiffs whose interests are only ‘arguably’ within a protected zone as upon plaintiffs whose interests are indeed protected.”109Caleb Nelson, “Standing” and Remedial Rights in Administrative Law, 105 Va. L. Rev. 703, 711 (2019). Instead, he argues, the APA, as originally understood, limits remedial rights to those who are actually aggrieved, as opposed to just arguably aggrieved.110See id. at 803.

On the other end of the spectrum, Professor Nicholas Bagley has criticized the Supreme Court’s recognition of a presumption of reviewability under the APA.111See Nicholas Bagley, The Puzzling Presumption of Reviewability, 127 Harv. L. Rev. 1285, 1289 (2014). As he has argued at length, “[t]he ostensible statutory source for the presumption—the Administrative Procedure Act (APA)—nowhere instructs courts to construe statutes to avoid preclusion.”112Id. at 1287 (footnote omitted). Instead of such a presumption, Professor Bagley has argued that courts should apply the APA’s statutory preclusion provision as written: “Where the best construction of a statute indicates that Congress meant to preclude judicial review, the courts should no longer insist that their participation is indispensable.”113Id. at 1340.

B. Standards of Review: Chevron, Auer, and Hard Look Review

Section 706 is the heart of the APA’s judicial review provisions, as it sets out the scope and standard of review for agency action. It instructs a reviewing court to “hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions” if one of a number of factors is present.1145 U.S.C. § 706(2). In particular, such judicial action is warranted when agency action is:

(A) arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law;

(B) contrary to constitutional right, power, privilege, or immunity;

(C) in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority, or limitations, or short of statutory right;

(D) without observance of procedure required by law;

(E) unsupported by substantial evidence in a case subject to sections 556 and 557 of this title or otherwise reviewed on the record of an agency hearing provided by statute; or

(F) unwarranted by the facts to the extent that the facts are subject to trial de novo by the reviewing court.115Id. § 706(2)(A)–(F).

Section 706 further instructs that the reviewing court “compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed”; “review the whole record or those parts of it cited by a party”; and take “due account . . . of the rule of prejudicial error.”116Id. § 706. Finally, section 706 provides that “the reviewing court shall decide all relevant questions of law, interpret constitutional and statutory provisions, and determine the meaning or applicability of the terms of an agency action.”117Id.

This Part focuses on two of the main judicial developments with respect to the APA’s standards of review: deference to administrative interpretations of law and arbitrary and capricious review. Part II.C. turns to judicial developments on the remedies front.

First, despite section 706 commanding a reviewing court to “decide all relevant questions of law,” the Supreme Court has embraced judicial deference doctrines regarding administrative interpretations of law. With respect to agency statutory interpretations, the Chevron doctrine commands courts to defer to an agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute the agency administers.118See Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 843 (1984). With respect to agency regulatory interpretations, the Auer doctrine commands courts to defer to an agency’s interpretation of its own regulation so long as the agency’s interpretation is not “plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.”119Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452, 461 (1997) (quoting Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co., 325 U.S. 410, 414 (1945)).

In recent years, some judges, scholars, and policymakers have criticized these deference doctrines, arguing, among other things, that they violate the constitutional separation of powers.120See generally Christopher J. Walker, Attacking Auer and Chevron Deference: A Literature Review, 16 Geo. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 103 (2018) (surveying key arguments leveled against Auer and Chevron). In 2018, the Supreme Court refused to overrule Auer deference121Kisor v. Wilkie, 139 S. Ct. 2400, 2408 (2019).—although Justice Kagan’s approach for the majority arguably cabins the doctrine in substantial respects.122See, e.g., Christopher J. Walker, What Kisor Means for the Future of AuerDeference: The New Five-Step Kisor Deference Doctrine, Yale J. on Regul.: Notice & Comment (June 26, 2019), https://perma.cc/VML7-W568. In casting the deciding vote, Chief Justice Roberts expressly noted that challenges to Chevron deference are still alive.123Kisor, 139 S. Ct. at 2425 (Roberts, C.J., concurring in part) (“Issues surrounding judicial deference to agency interpretations of their own regulations are distinct from those raised in connection with judicial deference to agency interpretations of statutes enacted by Congress.”).

Thousands of law review articles have been published on these deference doctrines, exploring many questions. For this Article’s purposes, though, the question is whether these judicial deference doctrines are consistent with the text of the APA. With respect to Chevron, Professor Aditya Bamzai has made the most compelling and comprehensive case that the deference doctrine is not consistent with the text, history, and structure of the APA.124See Aditya Bamzai, The Origins of Judicial Deference to Executive Interpretation, 126 Yale L.J. 908 (2017); see also Duffy, supra note 9, at 193–203 (raising similar arguments that the text of section 706 of the APA does not support Chevron deference). More recently, Professors Ronald Levin and Cass Sunstein have separately defended Chevron deference as a proper interpretation of the APA.125See Ronald M. Levin, The APA and the Assault on Deference, Minn. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2021), https://perma.cc/S9LL-GEP8; Cass R. Sunstein, Chevron as Law, 107 Geo. L.J. 1613, 1641–57 (2019); see also Kristin E. Hickman & David Hahn, Categorizing Chevron, 81 Ohio St. L.J. 611, 656–669 (2020) (defending Chevrondeference as a matter of statutory interpretation and responding to Bamzai, supra note 124). This Article does not take sides in this debate. It is sufficient to appreciate that the most natural textual reading of section 706’s instruction that courts shall “decide all relevant questions of law” is de novo or plenary review. But federal courts have not accepted that reading. Instead, the Supreme Court has read the APA to include certain deference doctrines to administrative interpretations of law.

Second, federal courts have interpreted section 706’s “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law” standard of review in ways that are in tension with the plain text and, indeed, at times in tension with each other. On the one hand, the Supreme Court has interpreted this arbitrary-and-capricious standard as thin rationality review126See Jacob Gersen & Adrian Vermeule, Thin Rationality Review, 114 Mich. L. Rev. 1355 (2016) (advocating for the more deferential approach set forth in Baltimore Gas & Electric Co. v. NRDC, 462 U.S. 87 (1983)). as well as a super-deference to scientific and technical determinations.127See Emily Hammond Meazell, Super Deference, The Science Obsession, and Judicial Review as Translation of Agency Science, 109 Mich. L. Rev. 733 (2011) (criticizing the Court’s deferential approach in Baltimore Gas, 462 U.S. at 87). On the other, the Supreme Court (in addition to lower courts) has adopted a “hard look” review that requires reasoned decision-making. In Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Ass’n v. State Farm Mutual Auto Insurance,128463 U.S. 29 (1983). the Court articulated this more searching approach:

[A]n agency rule would be arbitrary and capricious if the agency has relied on factors which Congress has not intended it to consider, entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the problem, offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the agency, or is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the product of agency expertise.129Id. at 43.

The Roberts Court has sent mixed messages on this front. Consider two recent decisions. In Department of Commerce v. New York (the census citizenship question case),130139 S. Ct. 2551 (2019). the Court made two substantial moves. First, the Court seemed to embrace thin rationality review, emphasizing “the choice between reasonable policy alternatives in the face of uncertainty was the Secretary’s to make” and the importance of “[w]eighing that uncertainty against the value of obtaining more complete and accurate citizenship data.”131Id. at 2569–71 (citing Baltimore Gas, 462 U.S. at 105); see also Dep’t of Commerce, 139 S. Ct. at 2571 (“By second-guessing the Secretary’s weighing of risks and benefits and penalizing him for departing from the Bureau’s inferences and assumptions, Justice Breyer—like the District Court—substitutes his judgment for that of the agency.”). Yet second, the Court held that under the APA’s “reasoned explanation requirement,” an agency must “offer genuine justifications for important decisions, reasons that can be scrutinized by courts and the interested public.”132Dep’t of Commerce, 139 S. Ct. at 2575–76. In other words, pretextual reasons are not sufficient.

Then last year, in Department of Homeland Security v. Regents of University of California (the DACA immigration relief rescission case),133140 S. Ct. 1891 (2020). the Court seemed to shift back to embracing a muscular version of hard look review. It held that arbitrary-and-capricious review under the APA requires the agency to consider reasonable regulatory alternatives and to demonstrate that it has adequately considered the reliance interests at stake in changing the regulatory baseline.134See id. at 1911–13. This decision is much more consistent with hard look review than the thin rationality review the Court embraced in the census citizen question case just one year prior.

Unlike many of the other examples in this Article, the Supreme Court’s conflicting approaches to arbitrary-and-capricious review may not be apt examples of judicial rewriting of the APA’s text. Instead, these conflicting approaches reveal the Court struggling to give meaning to the terms “arbitrary and capricious.” But the Court’s struggles and shifting interpretations of the APA’s critical standard of review should warn administrative lawyers to not take the statutory text at face value. A similar conclusion could be drawn about Auer and Chevron deference, though the argument that judicial deference doctrines are inconsistent with section 706’s statutory text seems stronger in that context.

C. Judicial Remedies: Remand Without Vacatur, Nationwide Injunctions, and Harmless Error

Until the last half-dozen years or so, the field gave little attention to questions of judicial remedies in administrative law.135See Nicholas Bagley, Remedial Restraint in Administrative Law, 117 Colum. L. Rev. 253, 256 (2017) (observing that questions about remedies “pervade administrative law, but they don’t get the attention they deserve”). Since then, however, such literature has exploded, especially in the context of the propriety of issuing a nationwide or universal injunction under the APA.

As mentioned in Part II.B., section 706 includes at least three provisions that deal with remedies. First, it authorizes courts to “hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions.”1365 U.S.C. § 706(2). Second, it authorizes courts to “compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed.”137Id. § 706(1). Courts have interpreted this ability to compel agency action quite narrowly. See, e.g., Heckler v. Chaney, 470 U.S. 821, 832 (1985) (concluding “that an agency’s decision not to take enforcement action should be presumed immune from judicial review under § 701(a)(2)” of the APA). See generally Daniel E. Walters, Symmetry’s Mandate: Constraining the Politicization of American Administrative Law, 119 Mich. L. Rev. 455 (2020) (surveying doctrines that insulate agency failures to regulate from judicial review and arguing against the existing asymmetry in the availability of judicial review for agency action compared to agency inaction). And third, it instructs that “due account shall be taken of the rule of prejudicial error.”1385 U.S.C. § 706. Section 705 also authorizes relief pending judicial review, including that the reviewing court “may issue all necessary and appropriate process to postpone the effective date of an agency action or to preserve status or rights pending conclusion of the review proceedings.”139Id. § 705. More recently, Professor John Harrison has argued that section 703 tells us as much if not more about judicial remedies under the APA than section 706. See generally John Harrison, Section 706 of the Administrative Procedure Act Does Not Call for Universal Injunctions or Other Universal Remedies, 37 Yale J. on Regul. Bull. 37 (2020). Exploring section 703’s potential effect on judicial remedies exceeds this Article’s ambition (and word limit). Section 702 also preserves the federal courts’ equitable remedial discretion.1405 U.S.C. § 702 (“Nothing herein (1) affects other limitations on judicial review or the power or duty of the court to dismiss any action or deny relief on any other appropriate legal or equitable ground; or (2) confers authority to grant relief if any other statute that grants consent to suit expressly or impliedly forbids the relief which is sought.”).

This Article focuses on three ways in which judicial doctrine seems in tension with section 706’s text. The first two consider what it means to “hold unlawful and set aside agency action.” In interpreting this provision, the Supreme Court has long embraced an “ordinary remand rule”: when a court concludes that an agency’s decision is erroneous, the ordinary course is to remand to the agency for additional investigation or explanation—as opposed to the court deciding the issue itself.141See, e.g., Negusie v. Holder, 555 U.S. 511, 517 (2009) (“When the BIA has not spoken on ‘a matter that statutes place primarily in agency hands,’ our ordinary rule is to remand to ‘giv[e] the BIA the opportunity to address the matter in the first instance in light of its own expertise.’” (quoting INS v. Ventura, 537 U.S. 12, 16–17 (2002) (per curiam))); see also Pierce, supra note 80, § 18.1. As I have detailed elsewhere, the ordinary remand rule applies not only to questions of fact, but also to the application of law to fact, policy judgments, and even certain questions of law.142See Christopher J. Walker, The Ordinary Remand Rule and the Judicial Toolbox for Agency Dialogue, 82 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1553, 1561–79 (2014); see also Henry J. Friendly, Chenery Revisited: Reflections on Reversal and Remand of Administrative Orders, 1969 Duke L.J. 199, 222–25 (1969) (trying to make sense of the general rule and its potential exceptions).

While this ordinary remand rule may seem consistent with section 706’s language of “hold[ing] unlawful and set[ting] aside,” courts have grafted onto the APA an exception to this general rule where the courts hold the agency action unlawful yet do not set it aside. That remedial doctrine is called remand without vacatur. As Professor Levin explores in the seminal article on the subject, remand without vacatur is a remedial innovation developed in the circuit courts over the last few decades, largely driven by the D.C. Circuit in the 1990s and 2000s.143See Ronald M. Levin, “Vacation” at Sea: Judicial Remedies and Equitable Discretion in Administrative Law, 53 Duke L.J. 291, 298–305 (2003). This remedial doctrine allows courts to declare an agency action arbitrary and capricious yet still keep it in place while the agency cures the procedural infirmities on remand. Once the agency has attempted to remedy those errors, challengers can then bring the modified action back to the court for further judicial review. If the agency action returns to court, the court considers the agency’s post-remand reasoning and actions as part of the administrative record.

In 2014, the Administrative Conference of the United States documented that, from 1972 through 2013, remand without vacatur has been used more than seventy times by the D.C. Circuit as well as at least once by the First, Third, Fifth, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and Federal Circuits.144Stephanie J. Tatham, The Unusual Remedy of Remand Without Vacatur 27 (2014). Despite that the APA does not expressly provide the remedy, the Administrative Conference recommended that “[r]emand without vacatur should continue to be recognized as within the court’s equitable remedial authority on review of cases that arise under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) and its judicial review provision, 5 U.S.C. § 706(2).”145Remand Without Vacatur, Administrative Conference of the U.S. Recommendation 2013–6, 78 Fed. Reg. 76,269, 76,273 (Dec. 17, 2013). In so recommending, the Administrative Conference noted:

[R]emand without vacatur is not without controversy. Some scholars argue that it can deprive litigants of relief from unlawful or inadequately reasoned agency decisions, reduce incentives to challenge improper or poorly reasoned agency behavior, promote judicial activism, and allow deviation from legislative directives. Critics have also suggested that it reduces pressure on agencies to comply with APA obligations and to respond to a judicial remand.146Id. at 76,272. In the DACA rescission case decided last year, the Supreme Court seemed to indirectly cast some doubt on remand without vacatur. See Christopher J. Walker, What the DACA Rescission Case Means for Administrative Law: A New Frontier for Chenery I’s Ordinary Remand Rule?, Yale J. on Regul.: Notice & Comment (June 19, 2020), https://perma.cc/2AJS-HVNF.

Or, as Professor Daniel Rodriguez has argued, “[t]he judicially created strategy of remand without vacatur should be disfavored precisely because it facilitates the use of more aggressive judicial scrutiny of agencies’ reasoning process.”147Daniel B. Rodriguez, Of Gift Horses and Great Expectations: Remands Without Vacatur in Administrative Law, 36 Ariz. St. L.J. 599, 601 (2004).

The second debate about section 706’s “set aside” language is whether it authorizes nationwide or universal injunctions to enjoin an agency rule beyond the parties challenging the rule in the particular legal challenge. The conventional understanding has been that the APA authorizes universal vacatur of an agency rule or other regulatory action. But in recent years, scholars have challenged that conventional account. In 2017, Professor Samuel Bray advanced the first comprehensive attack on nationwide injunctions, arguing that they are inconsistent with traditional equitable principles, the scope of “judicial power” under Article III of the U.S. Constitution, and good policy for judicial review.148See Samuel L. Bray, Multiple Chancellors: Reforming the National Injunction, 131 Harv. L. Rev. 417, 418 (2017). But see Suzette M. Malveaux, Class Actions, Civil Rights, and the National Injunction, 131 Harv. L. Rev. F. 56, 56 (2017) (disagreeing with Professor Bray and concluding that “[a]lthough national injunctions are imperfect and crude forms of justice, they are better than no justice at all—which for some actions, may be the alternative”). A number of scholars have come to the nationwide injunction’s defense, including Professors Amanda Frost, Mila Sohoni, and Alan Trammell.149See, e.g., Amanda Frost, In Defense of Nationwide Injunctions, 93 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1065 (2018); Mila Sohoni, The Lost History of the “Universal” Injunction, 133 Harv. L. Rev. 920 (2020); Mila Sohoni, The Power to Vacate a Rule, 88 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1121 (2020); Alan M. Trammell, Demystifying Nationwide Injunctions, 98 Tex. L. Rev. 67 (2019). Professors John Harrison and Michael Morley, moreover, have responded with other reasons why at least some universal injunctions are improper.150See Harrison, supra note 139; Michael T. Morley, Disaggregating Nationwide Injunctions, 71 Ala. L. Rev. 1 (2019).

These articles are unlikely to be the last word on the subject. Indeed, the issue has been swirling at the Supreme Court in recent years, and the Court has yet to provide a definitive answer.151See, e.g., Christopher J. Walker, More from Various Legal Scholars on the Nationwide Injunction, “Universal Vacatur,” and the APA, Yale J. on Regul.: Notice & Comment (Apr. 13, 2020), https://perma.cc/3F2Y-AVY2 (discussing Supreme Court amicus briefs on issue). But the debate underscores the unsettled nature of the scope of “set aside” in the APA and how the modern realities of administrative law—in particular, the rise of district judges issuing nationwide injunctions—should encourage Congress to intervene to modernize the APA.152See, e.g., Adam White, Congress Should Fix the Nationwide Injunction Problem with a Lottery, Yale J. on Regul.: Notice & Comment (Feb. 11, 2020), https://perma.cc/CA4V-BLT8.