Introduction

In 1981, Maine added a “nonsectarian” requirement to bar religious private schools from receiving generally available tuition assistance.1Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 1994 (2022); see Me. Stat. tit. 20-A, § 2951(2) (2021). The Supreme Court held in Carson v. Makin2142 S. Ct. 1987 (2022). that this nonsectarian requirement violated the Free Exercise Clause—Maine’s restrictions on religious use were really restrictions based on religious status.3Id. at 2001 (“In short, the prohibition on status-based discrimination under the Free Exercise Clause is not a permission to engage in use-based discrimination.”). Previously, under the status-use distinction, states could withhold generally available public funding based on religious use of funds, but not based merely on an entity’s religious status.4See Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 720–21 (2004). Carson rejected that distinction.5Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001. This raises the question of whether any limits remain on state aid to religious institutions after the status-use distinction’s demise.6See Leo O’Malley, Note, An Establishment Clause Eulogy: The Rise and Fall of the Status/Use Distinction, 37 Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 279, 297–98 (2023) (arguing the Court should use a more detailed analysis than Lemon with elements of Free Speech jurisprudence to determine Establishment Clause violations).

Private activity bonds are one type of public aid where religious use-based restrictions still frequently apply.7See, e.g., Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 390.922(c) (West, Westlaw through P.A.2024, No. 156, of the 2024 Reg. Sess.); Financing Programs: Eligibility, Conn. Health & Educ. Facilities Auth., https://perma.cc/74BQ-FSBR (to view the website, click “View the live page” after clicking the permalink). The bonds are credit issuances by state and local governments “that primarily benefit[] or [are] used by a private entity.”8Grant A. Driessen, Cong. Rsch. Serv.,RL31457, Private Activity Bonds: An Introduction 3 (2022). Though private activity bonds are normally taxed, certain private projects of nonprofit organizations, like building or renovating schools and hospitals, are tax exempt.9See id. at 1; see also 26 U.S.C. § 145(a). Yet state constitutions, restrictive enabling statutes, and bond authorities’ discretion can, in many states, prevent religious nonprofits from receiving public aid.10See Meir Katz, The State of Blaine: A Closer Look at the Blaine Amendments and Their Modern Application, 12 Engage: The Federalist Soc’y Rev., June 2011, at 111, 113; see also, e.g., Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 390.922(c) (West, Westlaw through P.A.2024, No. 156, of the 2024 Reg. Sess.); Financing Programs: Eligibility, supra note 7. For example, many use restrictions are based on Blaine amendments, which bar a state from providing public aid to “sectarian” institutions.11See, e.g., Mass. Gen. Laws. Ann. ch. 15A, § 10 (West, Westlaw through Ch. 129 of the 2024 2d Ann. Sess.) (barring tax-exempt bonds from funding acquisition or improvement of health or educational facilities “used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place of religious worship”). The authority to pass §§ 2–3 of the law comes from Mass. Const. art. XVIII, § 2, which prevents the disbursement of state aid to any institution “wherein any denominational doctrine is inculcated, or any other school, or any college, infirmary, hospital, institution, or educational, charitable or religious undertaking which is not publicly owned and under the exclusive control, order and superintendence of public officers.” For more information on Blaine amendments generally, see Katz, supra note 10, at 111–12, and Richard D. Komer, Trinity Lutheran and the Future of Educational Choice: Implications for State Blaine Amendments, 44 Mitchell Hamline L. Rev. 551, 563–64 (2018)..

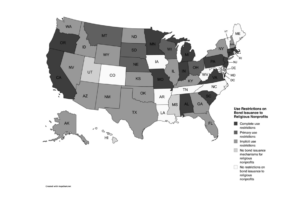

This Comment advocates that many statutory use restrictions, and the Blaine amendments which justify them, violate the Free Exercise Clause. This, in turn, requires both a taxonomy of the use-based restrictions in each state and a two-pronged approach to Blaine amendments’ unconstitutionality.

First, use restrictions in bond enabling statutes fall into three categories: (1) states whose statutory use restrictions apply to facilities where any religious instruction or worship occurs; (2) states whose statutory use restrictions apply to facilities primarily used for religious instruction or worship; and (3) states whose Blaine amendments implicitly prohibit bond issuance to religious institutions.12See, e.g., Mo. Rev. Stat. § 360.015(3) (1999) (defining an eligible education or health facility as a building not “used or to be used for sectarian instruction or study or as a place for religious worship”); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 58-812 (2013) (defining property eligible for bonds as not including “any property used or to be used primarily for sectarian instruction or study or as a place for devotional activities or religious worship”) (emphasis added)); Univ. of the Cumberlands v. Pennybacker, 308 S.W.3d 668, 671, 679 (Ky. 2010) (holding $10 million bond issue to Southern-Baptist-associated college violated Kentucky’s State Constitution). However, some states do not fall neatly into these categories. See, e.g., Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-4902 (West, Westlaw through the 2024 Reg. Sess. and 2024 Spec. Sess. I) (barring religious organizations from receiving industrial revenue bonds for construction or renovation of office space, theological training centers, and “facilities devoted to the staging of equine events”). This Comment calls the first category “complete” use restrictions, since they bar disbursing public funds for a facility where any religious activity occurs.13See, e.g., Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 390.922(c) (West, Westlaw through P.A.2024, No. 156, of the 2024 Reg. Sess.) (stating bonds cannot be used for “any facility used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place of religious worship”). This Comment calls the second category “primary” use restrictions, since they bar disbursing public funds for a facility primarily used or to be used for religious activity.14See, e.g., Neb. Rev. Stat. § 58-812 (2013) (stating bonds cannot be used for “any property which is used or to be used primarily in connection with any part of the program of a school or department of divinity for any religious denomination or the training of ministers, priests, rabbis, or other professional persons in the field of religion.” (emphasis added)). This Comment calls the final category “implicit,” since, though no statute explicitly bars bond issuance to religious institutions, bond authorities may still rely on a Blaine amendment to deny issuance.15See, e.g., Fla. Const. art. I, § 3 (“No revenue of the state or any political subdivision or agency thereof shall ever be taken from the public treasury directly or indirectly in aid of any church, sect, or religious denomination or in aid of any sectarian institution.”).

Complete use restrictions, being status restrictions merely worded as use restrictions, are facially unconstitutional.16See Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 2001 (2022); see also Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2026 (2017) (Gorsuch, J., concurring in part) (“I don’t see why it should matter whether we describe that benefit, say, as closed to Lutherans (status) or closed to people who do Lutheran things (use). It is free exercise either way.”). But many primary, and all implicit, use-based restrictions rely on Blaine amendments, which are constitutionally suspect.17See Christopher Tyler Prosser, The Locke Exception: What Trinity Lutheran Means for the Future of State Blaine Amendments, 46 Pepp. L. Rev. 621, 690 (2019) (“An analysis of state Blaine Amendments under the Court’s current jurisprudence would likely result in a finding that many, if not all, of these state constitutional provisions are facially unconstitutional under both the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses.”); Katz, supra note 10, at 115 (“In particular, Blaine Amendments are vulnerable to two types of federal constitutional claims: claims under the Equal Protection Clause and claims under the Free Exercise Clause.”); Richard W. Garnett, The Theology of the Blaine Amendments, 2 First Amend. L. Rev. 45, 50 (2003) (“[B]ecause state constitutions may neither authorize nor permit that which the Constitution of the United States has been interpreted to forbid, at least some of the Blaine Amendments are, in at least some of their applications, unconstitutional.” (footnote omitted)); Mark Edward DeForrest, An Overview and Evaluation of State Blaine Amendments: Origins, Scope, and First Amendment Concerns, 26 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 551, 625 (2003) (“It is likely that most state Blaine provisions violate both the Religion Clauses and the Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment.”). Two possibilities could resolve the problem of Blaine amendments: (1) deeming them and their use-restriction progeny unconstitutional, or (2) treating Blaine amendments as constitutional while finding a new test to avoid Free Exercise Clause violations. In the latter interpretation, primary and implicit use restrictions may be unconstitutional as-applied, necessitating a replacement to the status-use distinction.18See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001. The logical replacement option is the Supreme Court’s test in Hunt v. McNair,19413 U.S. 734 (1973). which applied the Lemon test to decide whether a bond program violated the Establishment Clause.20See id. at 741. With a few corrections, the Hunt test can instead become an analysis of whether the denial of bond issuance violates the Free Exercise Clause.

This Comment proceeds in five parts. Part I begins with a brief explanation of private activity bonds, followed by a chronology of First Amendment jurisprudence on state aid to religious institutions, both generally and with specific attention to bonds, and ends with a history of Blaine amendments. Part II categorizes use-based restrictions on bond issuance to religious institutions in all fifty states plus the District of Columbia. Part III advocates for the general unconstitutionality of Blaine amendments and for their repeal. Part IV outlines the Hunt test, modifies it to conform with current Supreme Court jurisprudence, and supports its modification as a replacement to the status-use distinction until the Supreme Court declares Blaine amendments unconstitutional. Finally, Part V applies the modified Hunt test to each category of the use-based restrictions from Part II and discusses possible limits and counterarguments to this test.

I. Background

A. Private Activity Bonds

Congress created the tax-exempt private activity bond in its current form in the Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968.21Driessen, supra note 8, at 1. While it did not change the substance of the private activity bond—an issuance of debt by a state or municipality to private entities for constructing or renovating private businesses—it did modify the standards for what makes bonds exempt from federal taxes.22Id. at 7; see Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968, Pub. L. No. 90-364, § 109, 82 Stat. 251, 269–70; 26 U.S.C. § 141(c). Generally, private activity bonds are subject to federal taxes unless they are also qualified private activity bonds.23See generally 26 U.S.C. §§ 103(b), 141(a). Most relevant for religious institutions is the qualified 501(c)(3) bond, which “[is] probably the most widely used type of qualified private activity bond[].”24Perry E. Israel, Summary of Federal Tax Requirements for Tax-Exempt Bonds, in The Handbook of Municipal Bonds 91, 116 (Sylvan G. Feldstein & Frank J. Fabozzi eds., 2012). States and municipalities issue qualified 501(c)(3) bonds to nonprofit organizations, including religious schools and hospitals, if they satisfy two elements.25See id.; see also 26 U.S.C. § 145(a). First, a 501(c)(3) must own the property that would benefit from the bond proceeds; second, the organization must use at least 95% of the bond proceeds for its tax-exempt purposes.26See 26 U.S.C. § 145(a). Although the Code states this as a three-part test, the last two parts are conjunctive and, thus, often combined. See Israel, supra note 24, at 116.

States have different mechanisms for issuing bonds. Some states issue bonds through state agencies; others through municipalities; and still others through independent corporations.27Compare, e.g., Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 3377.02 (West, Westlaw through the 136th Gen. Assemb. (2025-20256), 2025 H 96, and 2024 H.J.R. No. 8) (creating the Ohio Higher Educational Facility Commission, an agency of the State of Ohio), with Ala. Code §§ 16-17-2 (Westlaw through Act 2025-35 of the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (establishing a procedure for Alabama municipalities to authorize the incorporation of “educational building authorities” with the power to issue tax-exempt bonds to colleges and universities), and 45 R.I. Gen. Laws §§ 38.1-4(a) (LEXIS through Ch. 300 of the 2025 Sess. (except ch. 272–273)) (creating the Rhode Island health and educational building corporation, a quasi-public corporation capable of issuing bonds). In some cases, states set up multiple bond authorities for different types of nonprofits.28Take South Carolina, for example, with multiple bond authorities: The Educational Facilities Authority can issue bonds for colleges and universities; the counties, pursuant to the Hospital Revenue Bond Act, can issue bonds to hospitals and other medical facilities; and the Jobs-Economic Development Authority can issue revenue bonds to 501(c)(3) organizations, including religious schools. See S.C. Code Ann. § 59-109-30 (Westlaw through 2024 Act No. 225); § 44-7-1430 (Westlaw through 2024 Act No. 225); § 41-43-240 (Westlaw through 2024 Act No. 225); § 41-43-30 (Westlaw through 2024 Sess. of the Gen. Assemb.). Multiple bond authorities translate to multiple enabling statutes; a state might, for example, restrict bond issuance for religious postsecondary schools, but not religious hospitals.29This is the case in Michigan. Compare Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 390.922 (West, Westlaw through P.A.2025, No. 2, of the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (creating a complete use restriction on bond issuance to religious colleges and universities), with Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 331.33 (West, Westlaw through P.A.2025, No. 2, of the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (providing no explicit limit on bond issuance to religious hospital or healthcare facilities). But the tax exemption allows for “borrowing at a lower rate of interest than the market would otherwise impose,” creating not only incentives for potential borrowers, but also constitutional issues.30Darin Schultz, Note, Application of Religiously Restrictive Secular-Use Provisions in Tax-Exempt Revenue Bond Financing: Steele v. Industrial Development Board of Metropolitan Government Nashville, 56 Tax Law. 707, 709 (2003).

B. First Amendment Jurisprudence on State Aid to Religious Institutions

Bond issuance to religious institutions implicates three constitutional questions: First, when does bond issuance violate the Establishment Clause? Second, when does refusal to issue bonds violate the Free Exercise Clause? And third, is bond issuance direct or indirect state aid?

1. The Establishment Clause Question

The Supreme Court incorporated the Establishment Clause against the states in Everson v. Board of Education,31330 U.S. 1 (1947). upholding a New Jersey statute which reimbursed parents for money spent towards bussing students to parochial schools.32Id. at 17–18. The Court did so because of the statute’s general applicability and “neutral[ity] in its relations with groups of religious believers and non-believers.”33Id. at 18.

The Court expanded on Everson with Lemon v. Kurtzman34403 U.S. 602 (1971). in 1971, creating a systematic test to determine Establishment Clause violations.35Id. at 611–14. The well-known Lemon test goes as follows: The statute (1) must have a “secular legislative purpose,” (2) may not have a primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion, and (3) “must not foster ‘an excessive entanglement with religion.’”36Id. at 612–13 (quoting Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664, 674 (1970)).

The Court collapsed the second and third prongs in Agostini v. Felton,37521 U.S. 203 (1997). further explaining government advancement of religion and excessive entanglement with religion.38Id. at 219, 222–23, 230–33. The Agostini Court found government aid advances religion if it results in government indoctrination or if it defines recipients with respect to religion.39Id. at 230–31. Some considerations for this included “the character and purposes of the institutions that are benefited, the nature of the aid that the State provides, and the resulting relationship between the government and religious authority.”40Id. at 232 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Lemon, 403 U.S. at 615). This Lemon-Agostini framework was the controlling test for the Establishment Clause, with few exceptions, until the Court decided Kennedy v. Bremerton School District41142 S. Ct. 2407 (2022). in 2022.42See id. at 2427–29 (“[T]his Court long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot.”); see also Groff v. DeJoy, 143 S. Ct. 2279, 2289 (2023) (noting Lemon’s abrogation). For history and tradition exceptions prior to Kennedy, see American Legion v. American Humanist Ass’n, 139 S. Ct. 2067, 2088–89 (2019), and Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. 565, 576 (2014). For more on the Lemon–Agostini framework, see Martha Ratnoff Fleisher, Establishing Bonds Between Church and State: The Issuance of Tax-Exempt Bonds for Religious Institutions, 2 First Amend. L. Rev. 199, 206–07 (2004).

In Kennedy, a high school football coach sued his employer after he was fired for praying silently at midfield after games.43Kennedy, 142 S. Ct. at 2415–16. The Court held the school district could not justify firing Kennedy using the Lemon test.44Id. at 2427. Kennedy scrapped the Lemon–Agostini framework, instead using the “original meaning and history” of the Establishment Clause to determine violations of it.45Id. at 2428. However, given the relative novelty of private activity bonds, the history and tradition test is not illuminating on the constitutionality of disbursement of bonds to religious nonprofits. And without settled tradition to clarify the meaning of the First Amendment in this context, the constitutionality of bond issuance depends on analogy with the “original meaning” of the Establishment Clause.46See id.

The first municipal bond issued in the United States was by New York in 1812 to fund the construction of a canal; these bonds fell out of widespread use in the late 1830s.47See 1 Jerry W. Markham, A Financial History of the United States 154 (2002); Kenneth Durr, The Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board Gallery on Municipal Securities Regulation, Sec. & Exch. Comm’n Hist. Soc’y, https://perma.cc/63KU-6BE9. After the Civil War, municipal bonds regained popularity as a way to finance railroad expansion, but the railroad bubble eventually burst, leading to nearly $150 million in default by 1880.48Durr, supra note 47. To inspire bondholder trust and avoid state defaults, states created a new form of municipal bond—the industrial development bond—in the late 1930s.49SeeGina M. Torielli, Opining on the 501(c)(3) Tax-Free Bond Transaction: Avoiding Common Borrower’s Counsel Misconceptions, 31 Wm. Mitchell L. Rev. 147, 152 n.23 (2004); Note, Bedtime for [Industrial Development] Bonds?: Municipal Bond Tax Legislation of the First Reagan Administration, 48 Law & Contemp. Probs. 213, 218–19 (1985) [hereinafter Bedtime for Bonds]. The first such bonds were limited both in number and scope, requiring a “public purpose” for the bonds, usually being transportation infrastructure or manufacturing.50Bedtime for Bonds, supra note 49, at 219.

Only after the Great Depression did municipal bonds for projects other than public transportation infrastructure (including for nonprofit organizations) became an accepted practice.51Torielli, supra note 49, at 152–53. The Massachusetts Supreme Court was the earliest court to consider the First Amendment ramifications of issuing municipal bonds to religious institutions in 1968. Answering questions from the state Senate,52Opinion of the Justices, 236 N.E.2d 523, 524 (Mass. 1968). it opined that issuing bonds to religious colleges and universities would be constitutional under both the Federal Constitution and the Massachusetts Constitution if the educational institution were not “maintained for the training of ministers.”53Id. at 529. The Vermont Supreme Court would decide on a case about bond issuance to religious institutions only seven months later. See Vt. Educ. Bldgs. Fin. Agency v. Mann, 247 A.2d 68 (Vt. 1968). The court based its decision not on a historical and textual analysis, but merely an application of Everson.54Opinion of the Justices, 236 N.E.2d at 529.

The Supreme Court has addressed disbursing state aid to religious institutions in a variety of contexts. For example, the Court has investigated the Establishment Clause’s restrictions on state aid to religious colleges and universities multiple times. The foundational analysis occurred in a “trilogy” of cases:55See Mark Strasser, Death by a Thousand Cuts: The Illusory Safeguards Against Funding Pervasively Sectarian Institutions of Higher Learning, 56 Buff. L. Rev. 353, 390 (2008). Tilton v. Richardson,56403 U.S. 672 (1971). Hunt v. McNair,57413 U.S. 734 (1973). and Roemer v. Board of Public Works.58426 U.S. 736 (1976). Each case held state aid to a religiously affiliated higher education institution was constitutional.59Tilton, 403 U.S. at 688–89; Hunt, 413 U.S. at 749; Roemer, 426 U.S. at 766–67. Though the colleges at issue were religiously affiliated, the Court found none were “pervasively sectarian” such that granting state aid would endorse religion.60Tilton, 403 U.S. at 686–87; Hunt, 413 U.S. at 743–44; Roemer, 426 U.S. at 755–59. Hunt specifically held that bond issuance to a religious institution for a secular purpose did not violate the Establishment Clause.61Hunt, 413 U.S. at 749.

Further, if the Court found bond issuance to religious institutions constitutional even under the stringent Lemon test, it must certainly be constitutional after Kennedy overturned Lemon’s “ahistorical, atextual” approach.62See Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. Dist., 142 S. Ct. 2407, 2420–21, 2428 (2022). Also, the “pervasively sectarian” test had been functionally overturned before Kennedy in both Mitchell v. Helms63530 U.S. 793, 826 (2000) (plurality opinion). and Zelman v. Simmons-Harris.64536 U.S. 639, 649, 652 (2002). Justice Thomas’s plurality in Mitchell repudiated the pervasively sectarian test because “the religious nature of a recipient should not matter to the constitutional analysis, so long as the recipient adequately furthers the government’s secular purpose.”65Mitchell, 530 U.S. at 827. And the Zelman Court explicitly rejected the pervasively sectarian test in the context of direct aid.66Zelman, 536 U.S. at 652.

The last remaining test that would raise Establishment Clause questions about bond issuance was the status-use distinction of Locke v. Davey. 67540 U.S. 712 (2004). Before Carson, courts relied on the status-use distinction to determine when aid to religious institutions violated state constitutional provisions.68For the origin of the status-use distinction, see Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 723–25 (2004). For an exemplary application of the status-use distinction, see Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2023–24 (2017). In Locke, a student wanted to use funds from a state merit scholarship to pursue a pastoral ministry major—a use of funds the Court deemed impermissible under the Washington State Constitution.69See Locke, 540 U.S. at 717–18; see also Wash. Const. art. I, § 11. Under the status-use distinction, states could withhold funds from being spent on religious use, but not impose blanket restrictions on state aid based on religious status.70See Locke, 540 U.S. at 723–25. But now that Carsonhas limited Locke to its facts, no facial constitutional problems remain with bond issuance to religious institutions.71See Sarah Parshall Perry and Jonathan Butcher, With Carson v. Makin, the Supreme Court Closed the Book on Religious Discrimination in School Choice, The Heritage Found. 12 (Sept. 2, 2022), https://perma.cc/4A94-GUG9.

2. The Free Exercise Question

Because “the two Clauses express complementary values” but “conflicting pressures,” the Free Exercise Clause is also implicated here.72See Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 719 (2005). The Supreme Court has made clear that disqualifying religious institutions “from [a] generally available benefit ‘solely because of their religious character’” “‘effectively penalizes the free exercise’ of religion.”73Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 1997 (2022) (quoting Trinity Lutheran, 137 S. Ct. at 2021); see also Espinoza v. Mont. Dep’t of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2261 (2020). Further, the Court has held some use-based restrictions are really discrimination against religious character.74Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001; see also Trinity Lutheran, 137 S. Ct. at 2025–26 (Gorsuch, J., concurring in part); Espinoza, 140 S. Ct. at 2275 (Gorsuch, J., concurring) (“Not only is the record replete with discussion of activities, uses, and conduct, any jurisprudence grounded on a status-use distinction seems destined to yield more questions than answers. Does Montana seek to prevent religious parents and schools from participating in a public benefits program (status)? Or does the State aim to bar public benefits from being employed to support religious education (use)?”). Thus, refusing to issue bonds to religious institutions because they would carry out a secular purpose in a religious way would violate the Free Exercise Clause.75Cf. William J. Haun, Keeping Our Balance: Why the Free Exercise Clause Needs Text, History, and Tradition, 46 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 419, 435 (2023) (“Scalia preferred the formulaic abstraction (‘neutrality’ + ‘general applicability’ = no relief).”).

3. The Direct Versus Indirect Aid Question

The final constitutional question is whether bond issuance to religious institutions counts as direct or indirect state aid. Direct aid is funding or support that a state transfers to an institution without an intermediary.76Cf. Agostini v. Felton, 521 U.S. 203, 209–10 (1997). For example, in Agostini, New York adopted a direct aid program by sending public school teachers to teach remedial classes in parochial schools.77See id. at 208. Indirect aid is funding or support that a state transfers to an institution through a private intermediary, such as the tuition assistance program in Carson.78See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 1993. There, Maine channeled tuition funding to private schools in rural areas, using parents as middlemen.79See id.

Indirect aid does not implicate the Establishment Clause and so cannot be the basis for denying bond issuance.80See Hunt v. McNair, 413 U.S. 734, 745 n.7 (1973); Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664, 675 (1970); Steele v. Indus. Dev. Bd., 301 F.3d 401, 410 (6th Cir. 2002). But if a court holds bond issuance is direct aid, it implicates the Establishment Clause unless “genuinely independent . . . private choices” intervene.81See Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639, 650–51 (2002); see also Zobrest v. Catalina Foothills Sch. Dist., 509 U.S. 1, 9 (1993); Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 388, 399 (1983). There is a non-negligible argument that issuing tax-exempt bonds to nonprofits constitutes direct aid without private choice—it involves direct government interaction with the bond market and provides bond investors no choice of which institutions the bond proceeds go to.82See Jason M. Hall, Note, Financing Religious Educational Institutions with Tax-Exempt Public Bond Proceeds, 83 B.U. L. Rev. 685, 700–01, 704 (2003) (arguing governments provide direct aid to religious institutions by intervening in the bond market without allowing for investor choice). But see Trent Collier, Note, Revenue Bonds and Religious Education: The Constitutionality of Conduit Financing Involving Pervasively Sectarian Institutions, 100 Mich. L. Rev. 1108, 1136–39 (2002) (arguing that, though bond issuance is direct aid, investor choice is sufficient private choice to make Establishment Clause inapplicable). Yet the Supreme Court and many lower courts have indicated that conduit bond financing, like the private activity bonds discussed here, is indirect aid.83See Hunt, 413 U.S. at 745 n.7; Mueller, 463 U.S. at 396; see also Steele, 301 F.3d at 410; Va. Coll. Bldg. Auth. v. Lynn, 538 S.E.2d 682, 687 (Va. 2000). Thus, religious institutions receiving a tax break on their bonds does not alone implicate the Establishment Clause.

Since bond issuance is indirect aid and analogous to aid provisions historically in line with the First Amendment, neutral and generally applicable bond programs do not automatically run afoul of the Establishment Clause. On the contrary, refusing to issue bonds to an institution merely because they fulfill a secular purpose in a religious way violates the Free Exercise Clause.84See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2000. But that still leaves Locke v. Davey and its implication that state Blaine amendments can invalidate indirect aid to a religious institution without offending the Free Exercise Clause.85See Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 719, 725 (2004).

C. Blaine Amendments and State Aid to Religious Institutions

Although the Federal Blaine Amendment passed in the House by a vote of 180-7, it failed in the Senate, but lived on in other forms.86Steven K. Green, The Blaine Amendment Reconsidered, 36 Am. J. Legal Hist. 38, 59–60 (1992). Debate was heated in the Senate, and the proposed amendment floundered by only two votes—28 yeas and 16 nays, with 27 senators absent.87DeForrest, supra note 17, at 573. Because only 44 of the then-71 senators were present, and because the two-thirds requirement of Art. V is two-thirds of those present, the Blaine amendment needed 30 votes to pass. See 4 Cong. Rec. 5595 (1876); Nat’l Prohibition Cases, 253 U.S. 350, 386 (1920). Yet supporters of the Blaine Amendment were not content to let the proposal die with Article V’s processes, and so campaigned to introduce similar amendments into state constitutions.88DeForrest, supra note 17, at 573; Joseph P. Viteritti, Blaine’s Wake: School Choice, The First Amendment, and State Constitutional Law, 21 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 657, 673 (1998). By 1876, fourteen states had adopted Blaine-style legislation, and by 1890, twenty-nine states had adopted Blaine amendments into their constitutions.89DeForrest, supra note 17, at 573; Viteritti, supra note 88, at 673. Despite separation from the religious conflicts of the 1870s, many states incorporated Blaine-style language, with Alaska and Hawaii embracing Blaine amendments as late as the 1950s.90DeForrest, supra note 17, at 573; see Alaska Const. art. VII, § 1; Haw. Const. of 1950, art. IX, § 1. A few states with Blaine amendments adopted after the initial late-nineteenth-century wave claim that, despite “sectarian” language and an identical effect of barring public funds from religious institutions, their amendments are not Blaine amendments. See, e.g., Univ. of the Cumberlands v. Pennybacker, 308 S.W.3d 668, 681–82 (Ky. 2010) (noting 1890 state constitutional convention report showed no animosity toward Catholicism, so the amendment was not a Blaine amendment). As it stands, thirty-eight state constitutions have Blaine provisions.91These Blaine provisions are: Ala. Const. art. IV, § 73; Ala. Const. art. XIV, § 263; Alaska Const. art. VII, § 1; Ariz. Const. art. II, § 12; Ariz. Const. art. IX, § 10; Cal. Const. art. IX, § 8; Cal. Const. art. XVI, § 5; Colo. Const. art. V, § 34; Colo. Const. art. IX, § 7; Del. Const. art. X, § 3; Fla. Const. art. I, § 3; Ga. Const. art. I, § 2, ¶ VII; Haw. Const. art. X, § 1; Idaho Const. art. IX, § 5; Ill. Const. art. X, § 3; Ind. Const. art. I, § 6; Kan. Const. art. VI, § 6(c); Ky. Const. § 189; Mass. Const. amend. art. XVIII, § 2; Mich. Const. art. I, § 4; Mich. Const. art. VIII, § 2; Minn. Const. art. I, § XVI; Minn. Const. art. XIII, § 2; Miss. Const. art. VIII, § 208; Mo. Const. art. I, § 7; Mo. Const. art. IX, § 8; Mont. Const. art. X, § 6 (held unconstitutional in Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2260–63 (2020)); Neb. Const. art. I, § 4; Neb. Const. art. VII, § 11; Nev. Const. art. XI, § 10; N.H. Const. art. LXXXIII; N.M. Const. art. XII, § 3; N.Y. Const. art. XI, § 3; N.D. Const. art. VIII, § 5; Ohio Const. art. VI, § 2; Okla. Const. art. II, § 5; Or. Const. art. I, § 5; Pa. Const. art. III, §§ 15, 29; S.C. Const. art. X, § 11 (barring specifically state credit from religious institutions); S.C. Const. art. XI, § 4; S.D. Const. art. VI, § 3; S.D. Const. art. VIII, § 16; Tex. Const. art. I, § 7; Tex. Const. art. VII, § 5(c); Utah Const. art. I, § 4; Utah Const. art. X, § 9; Va. Const. art. IV, § 16; Va. Const. art. VIII, §§ 10, 11; Wash. Const. art. I, § 11; Wash. Const. art. IX, § 4; Wis. Const. art. I, § 18; Wyo. Const. art. I, § 19; Wyo. Const. art. III, § 36.

Blaine amendments, named after Representative (and later, Senator) James Blaine of Maine, prevent a state from providing public funds or property to “sectarian” schools and institutions.92See Katz, supra note 10, at 112; Komer, supra note 11, at 563–64. Spurred by a wave of anti-Catholicism leading up to the 1876 election, Blaine proposed an amendment to the Federal Constitution which would have prohibited states from aiding private religious schools with money drawn from the public treasury.93Katz, supra note 10, at 112; Viteritti, supra note 88, at 670. Blaine’s original proposed amendment reads: No State shall make any law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; and no money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefore, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect, nor shall any money so raised or lands so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations. 4 Cong. Rec. 205 (1875).

However, the Blaine Amendment was far from religiously neutral. At the time, public schools were “propagators of a generic Protestantism” and readings from the King James Bible and “devotional exercises” were commonplace because support for Protestant Christianity was seen as support for democratic values and morality.94DeForrest, supra note 17, at 559–60; see also Green, supra note 86, at 45. Opposition to the Blaine Amendment, therefore, was tantamount to support for “rum, Romanism [i.e., Catholicism], and rebellion.”95Karl E. Meyer, Move for Private-School Aid Agonizing to N.Y. Politicians, Wash. Post, Feb. 24, 1970, at A2; see also Republican Party, Republican Platform of 1876, reprinted in Kirk Porter & Donald Johnson, National Party Platforms, 1840-1964, at 54 (1966) (noting opposition to sectarian schooling was in the party platform). The Senate debates made no effort to conceal the anti-Catholic animus which inspired the Amendment, ascribing to Catholicism “dogmas [of intolerance that] . . . are at this moment the earnest, effective, active dogmas of the most powerful religious sect that the world has ever known.”964 Cong. Rec. 5588 (1876) (statements of Sen. George Edmunds). “[I]t was an open secret that ‘sectarian’ was code for ‘Catholic,’” and that Blaine amendments were “born of bigotry.”97Mitchell v. Helms, 530 U.S. 793, 828–29 (2000).

Blaine amendments do not all function identically. One way of categorizing them is by restrictiveness.98See, e.g., DeForrest, supra note 17, at 577–601 (analyzing Blaine amendments by restrictiveness). By this metric, Blaine amendments range from less to more restrictive—the least restrictive provisions have carveouts for government assistance for transportation to religious secondary schools or aid to religious higher education.99See id. at 577–78. Massachusetts is an example of a less restrictive provision. See Mass. Const. art. XLVI, § 2, amended by Mass. Const. amend. art. CIII (permitting grants to private higher educational institutions or to students or parents of students attending such institutions). In turn, the most restrictive provisions prohibit both direct and indirect aid to religious institutions, which may encompass private activity bonds.100See DeForrest, supra note 17, at 587. In the past, parties challenging government aid to religious institutions only invoked state Blaine amendments as an argument in the alternative.101For examples of parties using state Blaine amendments as an argument in the alternative, see, for example, Brief of Respondents at 28–44, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246 (2020) (No. 18-1195), 2019 WL 5887033 (arguing first that Free Exercise Clause justifies not funding religious institutions by ending private school aid program, and, in the alternative, Montana’s Blaine amendment can be more stringent than Establishment Clause), and Brief of Respondent at 8–20, Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012 (2017) (No. 15-577), 2016 WL 3548944 (similar argument regarding Missouri’s Blaine amendment). But since Kennedy has made “history and tradition” the test for Establishment Clause violations, and the Supreme Court has given teeth to the Free Exercise Clause, state Blaine amendments are the last justification for excluding religious institutions from generally available aid.102For the history and tradition test, see Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 142 S. Ct. 2407, 2428 (2022). For Blaine amendments as an effective argument to justify excluding religious institutions from even the indirect benefits of public aid, see Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 719, 722 (2004).

The prime example of such exclusion is Locke, where the Supreme Court found tuition assistance to a student majoring in pastoral ministry was verboten under the Washington State Constitution.103See Locke, 540 U.S. at 725; see also Wash. Const. art. I, § 11. Several litigants have argued Locke stands for the proposition that Blaine amendments constitute a historical opposition to funding religious institutions, and therefore justify such institutions’ exclusion from generally available state aid programs.104See, e.g., Espinoza v. Mont. Dep’t of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2258–59 (2020). But the Court has limited Locke to its facts, finding that training of clergymen is a sui generis category, the funding of which states have a “historic and substantial” pedigree of opposing.105See id. at 2257–58. Thus, Blaine amendments can prevent religious institutions from receiving generally available aid only if those institutions use state benefits to support something which the state has historically and traditionally opposed since the ratification of the Religion Clauses.106See id. at 2258.

Arguably, states have a long-held tradition against funding the construction and maintenance of places of worship.107See Locke, 540 U.S. at 723 (collecting state constitutional provisions barring state support of clergy or places of worship). But “place of worship” ought to be narrowly construed. Students and teachers at a religious school praying at the beginning of a science class do not transform a classroom into a place of worship.108For an example of a bond authority financing a science center at a religious school, see, for example, Md. Health & Higher Educ. Facilities Auth., 2020 Annual Rep. 11 (2020) (mentioning nearly $12 million in bonds issued to a Catholic school for construction of a new science center). Because “‘there is room for play in the joints between’ the . . . Clauses,” a thorough taxonomy of use-based restrictions is necessary to determine where accommodating religion turns into an establishmentarian practice.109Cutter v. Wilkinson, 544 U.S. 709, 713 (2005) (quoting Locke, 540 U.S. at 718).

II. Enabling Statutes and Religious Use-Based Restrictions

Currently, twenty-two states limit issuing tax-exempt bonds to religious nonprofits.110The states are Alabama, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin. For a chart of each state’s restrictions on bond issuance to religious nonprofits, see infra Appendix D. Each state’s limit can be categorized by its egregiousness.

When states limit religious nonprofits’ bond access, they use language preventing bonds from going to facilities used for sectarian instruction, religious worship, or devotional activities.111See, e.g., Ala. Code § 16-18A-2 (Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (barring bonds from supporting “any facility used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place of religious worship”); Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 39A-31 (West, Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (barring bonds from supporting “any property used or to be used primarily for sectarian instruction or study or as a place for devotional activities or religious worship”). As stated above, use restrictions can be complete, primary, or implicit.112See supra Introduction.

Some states lack both a restrictive bond enabling statute and a Blaine amendment.113See, e.g., N.C. Const. art. V, § 12. States in this category have either previously funded religious nonprofits, do not have publicly available evidence of funding nonprofits, or have no mechanism for issuing bonds to religious nonprofits.114Maryland, for example, has previously funded religious schools. See Md. Health & Higher Educ. Facilities Auth., supra note 108, at 11. Utah does not seem to have a way to fund religious nonprofits, or at least has not done so. See State Treasurer of Utah, Gen. Obligation Bonds, Series 2020B, at 110, 118 (2020) (mentioning that the only conduit bond issuer is the Utah Charter School Finance Authority, which, under the state constitution, cannot issue bonds to private institutions).

A. Taxonomy of Complete Use Restrictions

States with complete use restrictions clearly codify that religious nonprofits cannot receive tax-exempt bonds.115See, e.g., S.C. Code Ann. § 59-109-30(2) (Westlaw through 2024 Act No. 225). Complete use restrictions bar bond issuance based on religious use coextensively with status.116See id. A state may have complete use restrictions for only one type of tax-exempt bond; for example, Alabama has a complete use restriction prohibiting religious postsecondary institutions from receiving bonds but has implicit restrictions on bonds for religious primary and secondary schools.117Compare Ala. Code § 16-18A-2 (Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (stating a project “shall not include any facility used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place of religious worship nor any facility which is used or to be used primarily in connection with any part of the program of a school or department of divinity for any religious denomination”), with Ala. Code § 16-17-1 (Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (making no mention of facilities with religious purpose), and Ala. Code § 11-54-80 (Westlaw through Act 2025-19 of the 2025 Reg. Sess.)(similar). Thirteen states have some form of complete use restriction: Alabama, California, Connecticut, Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, and Virginia.118See infra Appendix A for a table of each complete use statute.

The archetypal complete use restriction reads as follows:

A structure or structures [eligible for private activity bonds] . . . shall not include any facility used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place of religious worship nor any facility which is used or to be used primarily in connection with any part of the program of a school or department of divinity for any religious denomination.119Ala. Code § 16-18A-2(2) (Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.).

Some complete use restrictions also add “devotional activities” after religious worship.120See, e.g., 24 Pa. Stat. and Cons. Stat. Ann. § 5503(2) (West, Westlaw through Act 151 of the 2024 Reg. Sess.).

Complete use restrictions present two main interpretive issues: the definitions of the three barred religious purposes, and the boundaries of what “used or to be used” means for a facility. No state defines “sectarian instruction,” “religious worship,” or “devotional activities” in its complete or primary use restrictions. Nor has the Supreme Court comprehensively outlined what these terms mean.121The Supreme Court has not exactly defined “sectarian instruction” even when presented with the opportunity, but Abington School District v. Schempp lists sufficient factors, including reading from a sectarian text and guided prayer. 374 U.S. 203, 206–07 (1963). The Court also implied “prayer, hymns, Bible commentary, and discussion of religious views and experiences” count as religious worship in Widmar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263, 265 n.2 (1981). While the Supreme Court has not defined devotional activities, the Seventh Circuit has commented that a broad interpretation of devotional activities is impractical. See Badger Catholic, Inc. v. Walsh, 620 F.3d 775, 781 (7th Cir. 2010) (“Quakers view communal silence as religious devotion, and a discussion leading to consensus as a religious exercise. Adherents to Islam and Buddhism deny that there is any divide between religion and daily life; they see elements of worship in everything a person does.”). If interpreted broadly, states could deny bonds to a religious school because an instructor begins class in brief prayer, or deny bonds to a religious hospital because a minister tends to be an adherent on his deathbed. Even if interpreted narrowly, a single instance of religious worship in a facility built or renovated through bonds could breach the recipient’s agreement with the bond authority.

The “used or to be used” language only exacerbates the issue. While use restrictions might include “to be used” to cover merely facilities yet-to-be-built, they impose limits on already built facilities too.122See Hunt v. McNair 413 U.S. 734, 736, 738, 744 (1973) (upholding a statute which allowed $1,250,000 in revenue bonds to facility improvements of a religious institution’s secular section only because “the Act specifically states that a project ‘shall not include’ any buildings or facilities used for religious purposes”). This functionally forces religious institutions to avoid acting religiously for fear of redemption or defeasance of the bonds.123See Internal Revenue Serv., Dep’t of Treasury, No. 59471F, Your Responsibilities as a Conduit Issuer of Tax-Exempt Bonds 5 (2019). Complete use restrictions thus punish recipient religious nonprofits for benign religious exercise even while they accomplish secular purposes like education or health. So, such restrictions are really based on status, punishing nonprofits for secular acts done religiously.124See Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2026 (2017) (Gorsuch, J., concurring in part) (“I don’t see why it should matter whether we describe that benefit, say, as closed to Lutherans (status) or closed to people who do Lutheran things (use). It is free exercise either way.”).

Connecticut and Virginia have unique use restrictions that do not use the above language, but may still be categorized as complete use restrictions.125See Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10a-178 (1967); Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-4902 (LEXIS through the 2025 Reg. Sess.). Connecticut’s restriction unabashedly allows only “nonsectarian” health care institutions to receive bonds.126Conn. Gen. Stat. § 10a-178(g) (1967). Virginia specifies that only “nonreligious organization[s]” may receive bonds, including bonds financing “facilities devoted to the staging of equine events and activities.”127Va. Code Ann. § 15.2-4902 (LEXIS through the 2025 Reg. Sess.). Being unequivocally status restrictions, these statutes too are facially unconstitutional.128See Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 2001 (2022).

B. Taxonomy of Primary Use Restrictions

States with primary use restrictions have looser standards compared to complete use restrictions because they restrict bond financing of facilities primarily devoted to sectarian instruction or religious worship. Five states fall in this category: Hawaii, Montana, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin.129See infra Appendix B for a table of all primary use restrictions. In addition, Ohio prevents tax-exempt bonds from financing college and university facilities “used exclusively as a place for devotional activities,” a verbiage which may be less constitutionally objectionable.130Ohio Rev. Code. Ann. § 3377.01 (West, Westlaw through File 1 of the 136th Gen. Assemb. (2025-2026)).

Hawaii’s primary use restriction is representative here:

[An eligible facility] does not include any property used or to be used primarily for sectarian instruction or study or as a place for devotional activities or religious worship or any property used or to be used primarily in connection with any part of a program of a school or department of divinity of any religious denomination.131Haw. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 39A-31 (West, Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.) (emphasis added).

The two main differences between primary and complete use restrictions are the addition of the word “primarily” and the more consistent inclusion of “devotional activities.”

Adding “primarily,” at first blush, seems to mitigate the interpretive problems of complete use restrictions. Not so. Primary use restrictions are merely status restrictions, modeled on the pervasively sectarian test disguised as use restrictions.132Compare Hunt v. McNair, 413 U.S. 734, 743 (1973) (“Aid normally may be thought to have a primary effect of advancing religion when it flows to an institution in which religion is so pervasive that a substantial portion of its functions are subsumed in the religious mission or when it funds a specifically religious activity in an otherwise substantially secular setting.”), with Neb. Rev. Stat. § 58-812 (2013) (“Property does not include any property used or to be used primarily for sectarian instruction or study or as a place for devotional activities or religious worship nor any property which is used or to be used primarily in connection with any part of the program of a school or department of divinity for any religious denomination or the training of ministers, priests, rabbis, or other professional persons in the field of religion.”). The Supreme Court coined the term “pervasively sectarian” in Hunt v. McNair to describe an institution whose religious mission was so integral to its actions that state support of those actions, even if ostensibly secular, amounts to an unconstitutional endorsement of religion.133See Hunt, 413 U.S. at 742–43. Primary use restrictions continue this “shameful pedigree” by viewing a religious institution carrying out a secular, public purpose only in light of the institution’s religious character.134See Mitchell v. Helms, 530 U.S. 793, 828 (2000). The Court explicitly rejected this test twice, shifting the analysis from the character of the institution to the means of funding and activity funded.135See id. at 826–29; Zelman v. Simmons-Harris, 536 U.S. 639, 654–55 (2002). Just as the Court has repudiated the pervasively sectarian test, so too is it likely to repudiate primary use restrictions.

Even without primary use restrictions, some bond issuances are still likely unconstitutional under Locke v. Davey. But if a restriction prevents a religious institution fulfilling a secular purpose from receiving bonds because the institution uses its constitutional right to free exercise, then that restriction is ripe for challenge.

C. Taxonomy of Implicit Use Restrictions

States with implicit use restrictions do not clearly restrict the issuance of tax-exempt bonds for religious nonprofits in bond-enabling statutes. However, bond authorities may refuse to issue bonds for projects involving religious facilities in light of state Blaine amendments. Some states have also clarified, through regulations or caselaw, that bond issuance to religious institutions runs afoul of the state Blaine amendment.136See, e.g., Pa. Dep’t of Cmty. & Econ. Dev., Bond Financing Program Guidelines 6 (2022), https://perma.cc/Q2J7-B9KB; Univ. of the Cumberlands v. Pennybacker, 308 S.W.3d 668, 679 (Ky. 2010). This category includes twenty-nine states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.137See infra Appendix C for a table of all implicit use restrictions.

Because all implicit use restrictions rely on Blaine amendments to invalidate bond issuance to religious institutions, the next logical step is to investigate how Blaine amendments are unconstitutional.138Although denials of bond issuance in states with implicit use restrictions must rely on Blaine amendments, only Michigan’s Blaine amendment arguably justifies such denials. Michigan’s Blaine provision states no “tax benefit, exemption, or deductions . . . shall be provided, directly or indirectly, to support the attendance of any student or the employment of any person at any such nonpublic school or at any location or institution where instruction is offered in whole or in part to such nonpublic school students.” Mich. Const. art. VIII, § 2 (emphasis added). Other courts considering whether conduit revenue bonds constitute a tax exemption that violates their Blaine provisions unanimously reject the idea. See Opinion of the Justices, 236 N.E.2d 523, 526–27 (Mass. 1968); Vt. Educ. Bldgs. Fin. Agency v. Mann, 247 A.2d 68, 69, 74 (Vt. 1968); Clayton v. Kervick, 267 A.2d 503, 507 (N.J. 1970), vacated, 403 U.S. 945 (1971); Hunt v. McNair, 177 S.E.2d 362, 369–70 (S.C. 1970), vacated, 403 U.S. 945 (1971); Nohrr v. Brevard Cnty. Educ. Facilities Auth., 247 So.2d 304, 307 (Fla. 1971); Cecrle v. Ill. Educ. Facilities Auth., 288 N.E.2d 399, 401–02 (Ill. 1972); Cal. Educ. Facilities Auth. v. Priest, 526 P.2d 513, 520–22 (Cal. 1974); Minn. Higher Educ. Facilities Auth. v. Hawk, 232 N.W.2d 106, 111–12 (Minn. 1975); State ex rel. Wis. Health Facilities Auth. v. Lindner, 280 N.W.2d 773, 783 (Wis. 1979); Health Care Facilities Auth. v. Spellman, 633 P.2d 866, 867–70 (Wash. 1981); Va. Coll. Bldg. Auth. v. Lynn, 538 S.E.2d 682, 699 (Va. 2000). If the state constitutional justifications for barring religious institutions from receiving bonds are not in line with the Federal Constitution, then neither are the bond denials.

III. The Unconstitutionality of Blaine Amendments

Blaine amendments are unconstitutional because they violate the Religion Clauses.139See, e.g., Prosser, supra note 17, at 690; Kyle Duncan, Secularism’s Laws: State Blaine Amendments and Religious Persecution, 72 Fordham L. Rev. 493, 499–502 (2003). While some commentators have noted Blaine amendments may also violate the Free Speech or Equal Protection Clauses, this Comment touches only on the Religion Clauses.140For the argument from the Free Speech Clause, see DeForrest, supra note 17, at 617–25. For the argument from the Equal Protection Clause, see Katz, supra note 10, at 115, and Garnett, supra note 17, at 54–55.

Any law burdening religious exercise must thread the needle between violating the Establishment Clause or the Free Exercise Clause.141See Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. Dist., 142 S. Ct. 2407, 2428 (2022); Abington Sch. Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 225 (1963) (“[T]he State may not establish a ‘religion of secularism’ in the sense of affirmatively opposing or showing hostility to religion . . . .”); Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520, 532–33 (1993). On one hand, a law violates the Establishment Clause if it explicitly benefits a particular religion at the expense of another religion, or “affirmatively oppos[es] or show[s] hostility to religion.”142See Schempp, 374 U.S. at 225. On the other hand, even a facially neutral law may excessively burden religious exercise, prompting strict scrutiny.143Lukumi, 508 U.S. at 532–33. In addition, a state may not justify a Free Exercise Clause violation by claiming merely that it tried to avoid an Establishment Clause violation.144See Kennedy, 142 S. Ct. at 2426–28. Finally, the Supreme Court now interprets the Religion Clauses as working together, not “warring” against each other.145Id. at 2426.

A. Establishment Clause Challenge

Under this framework, Blaine amendments violate both the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses. With the Establishment Clause, the use of “sectarian” as code for Catholic may provide the basis for a facial discrimination claim on the theory that favoring non-Catholic religions is an establishment of religion.146See Mitchell v. Helms, 530 U.S. 793, 828 (2000). In the alternative, a challenger may argue Blaine amendments categorically disadvantage religion qua religion. In response, states will likely make one of two counterarguments: (1) While Blaine amendments may have been “born of bigotry,” they now apply equally to all religions, and so do not favor any particular religion contrary to the Establishment Clause;147See id. at 828–29. For the widening interpretation of “sectarian” in enforcement of Blaine amendments, see Katz, supra note 10, at 113 (“Early enforcement of the Blaine Amendments confirms their discriminatory nature. . . . No majority religion is ‘sectarian’; it is a word that refers, usually pejoratively, to insular minority faith traditions. Thus, a rule barring funding to sectarian organizations permits the preferences of the majority to persist at the expense of the minority.”). or (2) the passage of the state Blaine amendment shows no animus to Catholicism or any other religion, so the amendment is not a Blaine amendment at all, but a neutral “no aid” provision.148See, e.g., Hile v. Michigan, 86 F.4th 269, 279 (6th Cir. 2023); Univ. of the Cumberlands v. Pennybacker, 308 S.W.3d 668, 681–82 (Ky. 2010).

The first counterargument is vulnerable to two criticisms. To begin, “sectarian” language inevitably targets minority religions—only minority faiths tend to be seen as “sectarian.”149See Katz, supra note 10, at 113. Next, even if states enforce Blaine amendments neutrally with respect to religion, they still misinterpret the rationale behind the Establishment Clause. The Establishment Clause does not “require unequal treatment of religious institutions, but . . . prevent[s] the use of government power to impose or induce religious uniformity.”150Nathan S. Chapman & Michael W. McConnell, Agreeing to Disagree: How the Establishment Clause Protects Religious Diversity and Freedom of Conscience 137 (2023). As it stands, Blaine amendments incentivize religious organizations to reduce or even eliminate their religious character to retain access to generally accessible benefits.151See id. at 133 (discussing Mueller v. Allen, 463 U.S. 388, 399 (1983), and its effect as a “bribe . . . to secularize”); see also Drummond ex rel. State v. Okla. Statewide Virtual Charter Sch. Bd., 558 P.3d 1, 8 (Okla. 2024). This alone establishes an unconstitutional “affirmative[] oppos[ition] or showing [of] hostility to religion.”152Abington Sch. Dist. v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203, 225 (1963).

The second counterargument fails because of its naïve nominalism: Blaine amendments are not unconstitutional merely for their name or peculiar history, but for their discrimination in practice against religion.153For examples of such discrimination in the enforcement of Blaine amendments, see DeForrest, supra note 17, at 608. For examples of laws with Blaine-like language that discriminate against religious institutions, see generally Nicole Stelle Garnett & Tim Rosenberger, Unconstitutional Religious Discrimination Runs Rampant in State Programs, Manhattan Inst. (Dec. 14, 2023), https://perma.cc/7YH8-523G. In other words, an amendment’s text, not the name of its sponsor, offends the Religion Clauses.154See Espinoza v. Mont. Dep’t of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2257–58 (2020) (“[T]he no-aid provision bars all aid to a religious school ‘simply because of what it is’ . . . . But no comparable ‘historic and substantial’ tradition supports Montana’s decision to disqualify religious schools from government aid.”). While the Federal Blaine Amendment’s history provides an independent justification for the unconstitutionality of state amendments, a state’s amendment need not be directly tied to the Federal Blaine Amendment to violate the Religion Clauses. To be clear, if a state constitutional provision bars state aid to religious institutions otherwise eligible for aid that is disbursed under neutral criteria, then that provision is a Blaine amendment, and so unconstitutional. However, the Supreme Court has rarely interpreted a law as violating the Establishment Clause because it expresses hostility to religion, choosing instead to find a violation of other First Amendment rights.155See, e.g., Rosenberger v. Rector & Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819, 845–46 (1995) (refusing religious student group access to facilities “was a denial of the right of free speech and would risk fostering a pervasive bias or hostility to religion, which could undermine the very neutrality the Establishment Clause requires”).

B. Free Exercise Clause Challenge

The more common, and more successful, challenge to state Blaine amendments arises under the Free Exercise Clause.156See, e.g., Espinoza, 140 S. Ct. at 2256 (“The Free Exercise Clause protects against even ‘indirect coercion,’ and a State ‘punishe[s] the free exercise of religion’ by disqualifying the religious from government aid as Montana did here.” (alteration in original) (quoting Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2022 (2017))). By differentiating religious institutions based on their religious character, Blaine amendments are subject to strict scrutiny.157See Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 1991 (2022); Espinoza, 140 S. Ct. at 2257; Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520, 546 (1993). “To satisfy strict scrutiny, government action ‘must advance “interests of the highest order” and be narrowly tailored in pursuit of those interests.’”158Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 1997 (quoting Lukumi, 508 U.S. at 546). Blaine amendments do neither.

First, Blaine amendments do not advance interests historically in line with the Religion Clauses.159See Espinoza, 140 S. Ct. at 2257–58. They take advantage of the “play in the joints” between the Establishment and Free Exercise Clauses, imposing strictures more stringent than the Establishment Clause demands.160See id. at 2254; see also Katz, supra note 10, at 115. Yet under current Free Exercise jurisprudence, state benefit programs can only exclude religious uses if a “historic and substantial” interest advises against funding that particular use.161See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2002 (quoting Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 722, 725 (2004)); Espinoza, 140 S. Ct at 2258–59. While states might have a “historic and substantial” interest against funding the construction and maintenance of churches, they have no similar interest against indirect funding of religious schools and hospitals.162For the possible “historic and substantial” interest against funding and maintenance of churches, see Locke, 540 U.S. at 723, 725 (collecting founding-era amendments barring tax funding of clergy and places of worship), and Vincent Phillip Muñoz, The Original Meaning of the Establishment Clause and the Impossibility of Its Incorporation, 8 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 585, 601 n.105, 609 (2006) (citing founding-era laws that closely tie tax funding of clergy with tax funding of places of worship). For the lack of a “historic and substantial” interest against indirect funding of religious schools, see Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001. For the lack of a “historic and substantial” interest against indirect funding of religious hospitals and medical facilities, see State ex rel. Wis. Health Facilities Auth. v. Lindner, 280 N.W.2d 773, 778 (Wis. 1979). These historic state interests are discrete and narrow categories unrepresentative of most funding schemes, so the overbroad language of Blaine amendments is bound to conflict with the Free Exercise Clause.

Second, even if states did have a substantial disestablishmentarian interest, Blaine amendments are not narrowly tailored to that end.163See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 1997. Blaine amendments everywhere along the continuum of restrictiveness bar religious institutions qua religious institutions from generally available aid.164See generally DeForrest, supra note 17 (providing an in-depth analysis of state Blaine amendments, including their language and motivations). Now that the status-use distinction is defunct, the claim that Blaine amendments are narrowly tailored against religious uses must fail.165See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001. Since state Blaine amendments cannot pass either part of the strict scrutiny analysis, they run afoul of the First Amendment and ought to be declared unconstitutional.

IV. The Status-Use Distinction’s Replacement

Carson did not consider the constitutionality of Blaine amendments.166See id. at 1993–94. And Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue167140 S. Ct. 2246 (2020). declined to declare Blaine amendments categorically unconstitutional.168See id. at 2259. Though holding Blaine amendments unconstitutional seems a logical outgrowth from Carson and Espinoza, Blaine provisions remain good law.169See supra note 91 and accompanying text. Considering it took eighteen years to bury the status-use distinction and fifty-one years to overturn the Lemon test, a substantial amount of time may pass before the high court intervenes.170Compare Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712, 723 (2004), and Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001, with Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 612–13 (1971), and Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. Dist., 142 S. Ct. 2407, 2428 (2022). Also, nearly thirty years elapsed before the “pervasively sectarian” test’s death. See Hunt v. McNair, 413 U.S. 734, 743 (1973); Mitchell v. Helms, 530 U.S. 793, 827 (2000). In the interim, the legality of bond issuance to religious institutions hinges on whether the benefited facility is functionally equivalent to a place of worship.171See Hunt, 413 U.S. at 740 n.4.

A. The Hunt Test

Carson and Espinoza did not overturn Locke because Locke relied on a “historic and substantial state interest” against using “taxpayer funds to support church leaders.”172See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2002 (quoting Locke, 540 U.S. at 722, 725); Espinoza, 140 S. Ct. at 2283. This historic interest against supporting church leaders at least arguably extends to funding the construction or maintenance of places of worship.173See Muñoz, supra note 162, at 601 n.105, 609 (citing founding-era laws that closely tie tax funding of clergy with tax funding of places of worship). But see Robert L. Cord, Founding Intentions and the Establishment Clause: Harmonizing Accommodation and Separation, 10 Harv. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 47, 50 (1987) (discussing President Jefferson’s authorization of funds for construction of Catholic church on mission to Kaskaskia Indians). If so, a proper replacement for the status-use distinction in the bond context must distinguish places of worship from facilities directed to a secular, public benefit. The best possibility for this is a test which modifies the Supreme Court case Hunt v. McNair.

In Hunt, a taxpayer challenged the constitutionality of revenue bond issuance to a Baptist-affiliated college in South Carolina.174Hunt, 413 U.S. at 735–36. The Baptist college intended to use the bonds to finance the construction of dining halls.175Id. at 738 n.2. Though South Carolina had a complete use restriction, the petitioner claimed such a statute was insufficient to prevent Establishment Clause violations.176Id. at 745–46.

Applying the Lemon test, the Hunt Court first determined that South Carolina’s bond-enabling statute had a secular legislative purpose and was generally available to both religious and secular institutions.177Id. at 741–42. Next, it concluded that aid to the college did not have the primary effect of advancing religion because the Baptist college was not “pervasively sectarian”—that is, “a substantial portion of its functions [were not] subsumed in the religious mission.”178Id. at 742–44. Finally, the Hunt Court dismissed petitioner’s concern that bond issuance to a religious college would constitute excessive entanglement between the state and religion.179Id. at 748–49. It reasoned that the college’s purpose was not “religious indoctrination,” and the state would not become impermissibly “involved in the day-to-day financial and policy decisions of the [c]ollege.”180Hunt, 413 U.S. at 745–47.

Hunt left numerous unanswered questions. Besides not clearly defining “pervasively sectarian,” the Court also did not interpret “sectarian instruction” or “religious worship.” Other courts interpreting similar complete use restrictions interpreted “pervasively sectarian” to mean an institution which has mandatory classes in the teachings of a particular religious tradition, in addition to religion-based admission restrictions.181See, e.g., Cal. Educ. Facilities Auth. v. Priest, 526 P.2d 513, 518 (Cal. 1974); Clayton v. Kervick, 285 A.2d 11, 20–21 (N.J. 1971) (citing Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672, 682 (1971)). Modifying Hunt’s test in light of Kennedy and Carson eliminates these opaque terms and brings the test in line with current Religion Clauses jurisprudence.

Implicit in Hunt is a four-part test to determine when a program permitting bond issuance to a religious institution violates the Establishment Clause.182See Hunt, 413 U.S. at 741–49; see also Cal. Statewide Cmtys. Dev. Auth. v. All Persons Interested, 152 P.3d 1070, 1077 (Cal. 2007) (“(1) The bond program must serve the public interest and provide no more than an incidental benefit to religion; (2) the program must be available to both secular and sectarian institutions on an equal basis; (3) the program must prohibit use of bond proceeds for ‘religious projects’; and (4) the program must not impose any financial burden on the government.”). It requires that aid (1) must serve a secular, public interest, (2) must be available to both secular and religious institutions, (3) must not benefit religious projects or pervasively sectarian institutions, and (4) must not require government involvement in “day-to-day financial and policy decisions.”183Hunt, 413 U.S. at 747; see All Persons Interested, 152 P.3d at 1077 (distilling an application of the Lemon test in the bond context to a four-part test). With some modification to conform to recent Supreme Court cases, the Hunt test can effectively replace the status-use distinction until the Court deals with Blaine amendments. Such a test, if applied, would also correctly render most use-based restrictions unconstitutional.

B. Modifying the Hunt Test

Because the Hunt test is based on the Lemon test and a “pervasively sectarian” inquiry, it needs substantial changes to align with current Religion Clauses jurisprudence. The first prong needs a change to prevent strategic action. The third prong of the original Hunt test is now unconstitutional in light of Kennedy and Carson.184Kennedy overturned Lemon’s effects test. See Kennedy v. Bremerton Sch. Dist., 142 S. Ct. 2407, 2427 (2022). Carson rejected the status–use distinction. See Carson ex rel. O.C. v. Makin, 142 S. Ct. 1987, 2002 (2022).

Hunt’s first prong comprises Lemon’s first prong, requiring a bond program to have a secular purpose.185Compare Hunt, 413 U.S. at 741, with Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 612–13 (1971). True, Kennedy has since recognized the abandonment of Lemon and its “abstract[] and ahistorical” test, noting its replacement with a “history and tradition” test.186Kennedy, 142 S. Ct. 2427. But the secular purpose requirement is likely necessary for general applicability.187See id. at 2421–22. To prevent religious institutions from reframing the first prong to permit funding the construction of places of worship on the ground it may serve the public interest downstream, the first prong should be amended. Instead of serving “the public interest,” it ought to directly serve a secular public interest. That way, courts need not punish religious institutions for acting religiously, so long as those institutions directly act for a secular public interest. Education and health easily meet this prong, and it does not allow for cleverly arguing that building a church has a secondary secular benefit.188For education being a secular public interest, see Tilton v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 672, 679 (1971). For health being a secular public interest, see Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 664, 687 n.8 (1970) (Brennan, J., concurring). This also dispenses with the need to define “place of worship,” since it takes a negative-functional approach: A place of worship, in the private activity bond context, is a building associated with a religious institution that does not directly serve a secular public interest.

The second prong comports with the requirements of the Religion Clauses.189See Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 1996–97; Espinoza v. Mont. Dep’t of Revenue, 140 S. Ct. 2246, 2260–61 (2020). By including religious institutions on the same level as secular, it does not “penalize[] the free exercise of” religion.190Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer, 137 S. Ct. 2012, 2020 (2017) (quoting McDaniel v. Paty, 435 U.S. 618, 626 (1978) (plurality opinion)).

By contrast, Hunt’s third prong unconstitutionally relies on the status-use distinction by strictly prohibiting all aid for “religious activity” and “pervasively sectarian” institutions.191Hunt v. McNair, 413 U.S. 734, 743 (1973). Since the statute at issue in Hunt was a complete use restriction, the Supreme Court implicitly defined a “religious project” as a project involving a facility “used or to be used for sectarian instruction or as a place for religious worship.”192Id. at 736(quoting S.C. Code Ann. § 22-41.2(b) (Supp. 1971)). The Court in Carson held this kind of status-masquerading‑as‑use restriction “lack[ing] a meaningful application.”193Carson, 142 S. Ct. at 2001. Because of this, the third prong should be cut from the test.

The final prong of the Hunt test is a formality, though an important one. It prevents bond issuance from imposing a financial or institutional burden on the state, which could happen if a participating institution fails to comply with the bond agreement.194See, e.g., Cal. Educ. Facilities Auth. v. Priest, 526 P.2d 513, 521 (Cal. 1974). Yet most, if not all, bond programs for nonprofits are conduit bonds rather than general obligation bonds.195See, e.g., Ala. Code. § 16-18A-6 (Westlaw through the 2025 Reg. Sess.). For bonds to nonprofits being conduit bonds, see What Are Municipal Bonds, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n (June 5, 2024), https://perma.cc/E7TL-ZNDK. While municipal governments are responsible for the debt of general obligation bonds, the borrowers themselves are responsible for the debt of conduit bonds.196See What Are Municipal Bonds, supra note 195. Thus, if a borrower does not comply with the bond agreement, the burden to pay for the defaulted bond does not shift to taxpayers.197See id. This prong also helps weed out applicants who try to secure government aid to construct a place of worship because it requires potential borrowers to be able to repay the bonds through revenue from the financed project. Presumably, most places of worship could not make enough money to pay back the bond’s value. Like the first and second prongs, this last one is constitutional but can be implicit since functionally all bond programs of this kind are conduit bonds.

With these modifications, the new Hunt test reads as follows: Refusal to issue conduit bonds to religious institutions violates the Free Exercise Clause when (1) the bond issuance would finance a project that directly serves a secular, public interest, or (2) the bond program is not available to both secular and religious institutions on an equal basis.

V. Applications and Concerns

Using the modified Hunt test, even if the Supreme Court does not hold Blaine amendments unconstitutional, state courts can still strike down religious-use-based restrictions. This Part applies the modified Hunt test to representative examples of complete, primary, and implicit use restrictions.

A. Complete Use Restrictions

The clear choice for the modified Hunt test’s first application is Hunt itself. First, the revenue bond issuance directly advanced a secular, public purpose—college dining halls further state interests in health and education. Second, South Carolina’s bond program was available to both religious and secular colleges and universities.198See Hunt v. McNair, 413 U.S. 734, 741–42 (1973) (quoting S.C. Code Ann. § 22-41.2(b) (Supp. 1971)). But, unlike under South Carolina’s complete use restriction, the Baptist college would not violate the bond’s terms if its dean decided to pray before the student body in the dining hall.

For another application, turn to California Educational Facilities Authority v. Priest.199526 P.2d 513 (Cal. 1974). In Priest, the state treasurer refused to honor bond sales authorized by the California Educational Facilities Authority to the University of the Pacific.200Id. at 514. The university intended to use the bonds to build dormitories, academic facilities, and other buildings essential to running a higher-educational institution.201Id. at 515–16. Though the University of the Pacific was not affiliated with a religious denomination, the California Supreme Court still considered whether the state’s Blaine provision categorically barred the sale of bonds to religious institutions.202Id. at 516 n.5. University of the Pacific was, at one point, associated with the United Methodist Church. Pacific’s United Methodist Affiliation, Univ. of the Pacific, https://perma.cc/JAT9-ZRCP. Ultimately relying on a combination of Lemon and Hunt, the court held that bond sales to religious colleges and universities did not violate either the Federal or State Constitutions.203Priest, 526 P.2d at 517–18, 522. Yet the court held the bond sale passed constitutional muster only because of a complete use restriction in the Educational Facilities Authority’s enabling statute.204Id. at 518–19 (citing California Educational Facilities Authority Act, ch. 1432, Stats. 1972, § 30303 (1972) (codified as amended at Cal. Educ. Code § 94110 (West, Westlaw through Ch. 103 of 2025 Reg. Sess.)).