Introduction

“Ever since Congress overwhelmingly passed and President Benjamin Harrison signed the Sherman Act in 1890,” recounts the Supreme Court, “‘protecting consumers from monopoly prices’ has been ‘the central concern of antitrust.’”1Apple, Inc. v. Pepper, 139 S. Ct. 1514, 1525 (2019) (citation omitted).

Not exactly. Although that more or less describes today’s understanding of Congress’s landmark legislation, it sweeps decades of muddled antitrust thinking under the rug. The truth is, the federal government and the Supreme Court struggled to apply Congress’s broadly worded antitrust statute for almost eighty years. Neither had a sound method for sorting procompetitive business actions from anticompetitive ones. So they relied instead on gut instinct: that big is bad.2See Joshua D. Wright, Elyse Dorsey, Jonathan Klick, & Jan M. Rybnicek, Requiem for a Paradox: The Dubious Rise and Inevitable Fall of Hipster Antitrust, 51 Ariz. St. L.J. 293, 298–302 (2019). As it turns out, that I-know-it-when-I-see-it approach led to scattershot enforcement decisions, higher prices, and lower output.3Id. at 300.

All that changed in the 1970s. Led primarily by the Chicago School of Economics and Robert Bork, economists persuaded the government, courts, scholars, and practitioners that antitrust laws should be rooted in empirical evidence.4Id. at 303–05. After some finetuning, that idea became a bipartisan consensus: antitrust laws should protect consumers and the benefits they receive from a competitive marketplace—lower prices, higher-quality goods, innovative products, increased productivity, and so on.5Id. at 364.

Known as the “consumer welfare standard,” this understanding still enjoys widespread support today.6Id. at 308; see also John Kwoka, Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies 1 (2015); Michael Vita & F. David Osinski, John Kwoka’s Mergers, Merger Control, and Remedies: A Critical Review, 82 Antitrust L.J. 361, 362–63 (2018). But that support is not universal. As the United States grapples with growing concerns over headline issues like income inequality, some have called for a new approach to antitrust enforcement.7See, e.g., Jonathan B. Baker & Steven C. Salop, Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Inequality, 104 Geo. L.J. Online 1, 24 (2015), https://perma.cc/NU73-62NH (“[A]ntitrust law and regulatory agencies could address inequality more broadly by treating the reduction of inequality as an explicit antitrust goal.”).

Except the approach isn’t new. It’s a return to the antitrust doctrines of yesteryear—when the government thought big is bad, small is good, and inefficiency and higher prices are sometimes worth it (“it” often left undefined).8See Wright et al., supra note 2, at 299–302. To be sure, some scholars would tweak the old approach here and there.9See, e.g., Lina M. Khan, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 Yale L.J. 710 (2017). At bottom, though, they’d have the government return to using the blunt instrument of antitrust enforcement to pursue policy goals beyond protecting consumers. This approach has spilled over into politics, too, catching the eye of the contemporary left and the populist right.10Daniel A. Crane, Antitrust’s Unconventional Politics, 104 Va. L. Rev. Online 118, 118 (2018) (“To the bewilderment of many observers, the ascendant pressures for antitrust reforms are flowing from both wings of the political spectrum, throwing into confusion a conventional understanding that pro-antitrust sentiment tacked left and antitrust laissez faire tacked right.”).

But this new-old approach is still an outlier. So much so that it’s been derisively dubbed “Hipster Antitrust.”11Ganesh Sitaraman, Unchecked Power: How Monopolies Have Flourished—and Undermined Democracy, The New Republic (Nov. 29, 2018), https://perma.cc/CL9X-KFRH. (More charitably, it might be called “Neo-Brandeisian Antitrust,” after Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, who believed big really was bad.12Kristian Stout, Big Tech and the Regressive Project of the Neo-Brandeisians, Law & Liberty (June 1, 2020), https://perma.cc/NU73-62NH.) Whatever the name, it comes with considerable baggage: decades’ worth of evidence and experience proving that the consumer welfare standard works remarkably well.

Savvy sympathizers of the movement realize this. Rather than call for full-scale reform, they market their ideas as mere “updates” to antitrust doctrine.13See, e.g., Kevin Caves & Hal Singer, When the Econometrician Shrugged: Identifying and Plugging Gaps in the Consumer Welfare Standards, 26 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 395, 396 (2018) (advocates for “innovation-based” theories of harm to “plug” gaps left by the consumer welfare standard); C. Scott Hemphill & Nancy L. Rose, Mergers That Harm Sellers, 127 Yale L.J. 2078, 2091 (2018) (arguing that, when it comes to monopsony harms, a “trading partner welfare” standard should be used); Suresh Naidu, Eric A. Posner & E. Glen Weyl, Antitrust Remedies for Labor Market Power, 132 Harv. L. Rev. 536, 587 (2018) (arguing that, in merger reviews, a “worker welfare” standard should be used instead of the consumer welfare standard). Even savvier scholars claim their desired policy goals are achievable under existing doctrine—no changes necessary.14See, e.g., Consumer Welfare Standard in Antitrust: Outdated or a Harbor in a Sea of Doubt: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Antitrust, Competition & Consumer Rights of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 115th Cong. 8 (2017) (statement of Diana Moss, President, American Antitrust Institute) (available at https://perma.cc/K3C8-HMF3). But with just a little digging, their shallow treatment of case law and shoehorning of evidence gives it all away: their arguments rest on substituting “social welfare” (as they envision it) for “consumer welfare” and “subjective” for “standard.”15See infra Part IV.

Such is the case in a series of recent papers written by Professor Fiona M. Scott Morton and David C. Dinielli.16Fiona M. Scott Morton & David C. Dinielli, Roadmap for a Digital Advertising Monopolization Case Against Google, Omidyar Network (May 2020), https://perma.cc/24GF-EUGM; Fiona M. Scott Morton & David C. Dinielli, Roadmap for an Antitrust Case Against Facebook, Omidyar Network (June 2020), https://perma.cc/KFB7-DMUF [hereinafter Roadmap]; Fiona M. Scott Morton & David C. Dinielli, Roadmap for a Monopolization Case Against Google Regarding the Search Market, Omidyar Network (June 2020), https://perma.cc/V2QB-S6JZ. The duo has so far published three under the title “Roadmap for an Antitrust Case Against . . .” Google, Facebook, and Google again.17See Roadmap, supra note 16. As I explained elsewhere in a response to their first paper against Google, there is no antitrust case against either company.18Christopher Marchese, Is Google Search an Advertising Goliath? Think Again—Competition in Digital Advertising Is Strong & Growing Stronger, NetChoice (June 2020), https://perma.cc/93EA-8AN2.

This Article, though, focuses solely on debunking Scott Morton and Dinielli’s claims that Facebook is a monopoly and that it harms users, advertisers, and publishers. As this Article shows, Facebook is popular, but it’s no monopoly. And it shows that consumers benefit immensely from Facebook.

I. Setting the Scene

A. The Social Network

In 2004, Mark Zuckerberg and other Harvard students launched TheFacebook.19Facebook Launches, History.com (Oct. 24, 2019), https://perma.cc/JW9S-WVEN. The platform initially allowed only Harvard students to join.20Id. But within a year, TheFacebook dropped the The and opened to students from other colleges.21Mark Hall, Facebook, Encyclopedia Britannica (May 29, 2019), https://perma.cc/CB2V-HGD2. By 2006, Facebook was open to anyone thirteen or older with an email address.22Id. Today, roughly two-thirds of Americans have joined the site, as have 2 billion people worldwide.23Sarah Aboulhosn, 18 Facebook Facts Every Marketer Should Know in 2020, Sprout Social (May 4, 2020), https://perma.cc/A8R2-VZAB.

Safe to say, Facebook is the social network—at least for now. Even as the platform attracts billions of users, adapts to changing consumer tastes, innovates and improves, Facebook faces fierce competition.24See infra Part III. It is neither as dominant as its critics claim, nor as safe as it would prefer.25See Facebook, Inc., Form 10-K for FY Ended Dec. 31, 2019, at 7, https://perma.cc/MR5V-8CAH (“We face significant competition in every aspect of our business, including from companies that facilitate communication and the sharing of content and information, companies that enable marketers to display advertising, companies that distribute video and other forms of media content, and companies that provide development platforms for applications developers.”). The platform that has attracted nearly seventy percent of Americans has also seen younger Americans jump to competitors.26See Mary Hanbury, Gen Z Says Facebook is the Number One Social-Media Platform They’ve Abandoned, Bus. Insider (July 8, 2019), https://perma.cc/RJK5-8KE3; Matt Rosoff, Facebook Exodus: Nearly Half of Young Users Have Deleted the App From Their Phone in the Last Year, Says Study, CNBC (Sept. 5, 2018, 12:18 PM), https://perma.cc/3Q6B-BCE7. The platform that has made billions in advertising revenue has also seen those advertisers boycott it.27Nancy Scola, Inside the Ad Boycott That Has Facebook on the Defensive, Politico Magazine (July 3, 2020, 3:15 PM), https://perma.cc/CKA3-3JSK; see also Rick Santorum, Why Corporations Should Not Bow to the Mob, Spectator USA (July 2, 2020, 3:14 AM), https://perma.cc/UG8R-LPNJ. And the platform that was once heralded as an American success story has also been raked over the coals by American politicians.28See, e.g., Pete Schroeder, Facebook’s Zuckerberg Grilled in U.S. Congress on Digital Currency, Privacy, Elections, Reuters (Oct. 23, 2019, 6:06 AM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-facebook-congress/facebooks-zuckerberg-grilled-in-u-s-congress-on-digital-currency-privacy-elections-idUSKBN1X2167.

Facebook’s founding motto was “move fast and break things.”29Samantha Murphy, Facebook Changes Its ‘Move Fast and Break Things’ Motto, Mashable (Apr. 30, 2014), https://mashable.com/2014/04/30/facebooks-new-mantra-move-fast-with-stability/. That it did. The platform quickly expanded from the elite halls of Harvard to the American mainstream.30Hall, supra note 21. In doing so, it broke MySpace’s dominance in social networking—a feat once thought unimaginable.31See Victor Keegan, Will MySpace Ever Lose Its Monopoly?, The Guardian (Feb. 8, 2007, 7:41 AM), https://perma.cc/ERU2-P6PC; Ryan Bourne, Is This Time Different? Schumpeter, the Tech Giants, and Monopoly Fatalism, Cato Institute (June 17, 2019), https://perma.cc/T8QJ-6ZYP (recounting reports of MySpace’s alleged monopoly in social media). And it broke the comfortable channels of news, commentary, and thought that traditional media, and the political class reliant on it, controlled.

Facebook gave all Americans a stage, a microphone, and an audience, all the while connecting those Americans to their friends and family, matching consumers with businesses large and small, and mixing silly with serious, professional with personal. It became, in other words, whatever each of us wanted it to be.

With the decades-old status quo extinguished, Facebook forever changed how we interact online. But despite all this breaking—of limits, expectations, possibilities—Facebook could not break one truism in technology: innovation and the competition it unleashes are always lurking.

Facebook faces pressure from outside the marketplace, too. Like its competitors, Facebook finds itself in the crosshairs of this decade’s culture wars.32See, e.g., McKay Coppins, The Billion-Dollar Disinformation Campaign to Reelect the President, The Atlantic (Feb. 10, 2020, 2:30 PM), https://perma.cc/6RLN-5VUH; Kate Conger & Sheera Frenkel, Dozens at Facebook United to Challenge Its ‘Intolerant’ Liberal Culture, N.Y. Times (Aug. 28, 2018), https://perma.cc/Z2SU-GAM4. The left criticizes the platform for not removing enough content that it believes is dangerous to American democracy;33See, e.g., Dean DeChiaro, Democrats Increase Pressure on Facebook Over Content Policies & Trump Posts, Roll Call (June 16, 2020), https://perma.cc/HE6M-QWEZ. the right says the opposite, that it removes too much content and that any such censorship undermines American values like free speech.34See, e.g., David Shepardson, Facebook, Google Accused of Anti-Conservative Bias at U.S. Senate Hearing, Reuters (Apr. 10, 2019, 5:35 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-congress-socialmedia/facebook-google-accused-of-anti-conservative-bias-at-u-s-senate-hearing-idUSKCN1RM2SJ. Implicit in both criticisms is a recognition of Facebook as an institutional force that needs to be reckoned with, lest it (i.e., its users) continue to compete with society’s gatekeepers (e.g., traditional media, the political class, elites).

This recognition has led some on the left and right to rediscover an old tool: use of antitrust to pursue political ends.35See, e.g., Mark Jamison, Are Regulatory Attacks on Big Tech Politically Motivated?, Am. Enter. Inst. (Sept. 30, 2019), https://perma.cc/6GB2-KYPB; Kevin O’Connor, The Political Attack on Big Tech, Wall St. J. (Sept. 23, 2019, 7:00 PM), https://perma.cc/E56E-RNBH; Eric Boehm, The Justice Department’s ‘Big Tech’ Antitrust Investigation is Unnecessary Political Theater, Reason (July 24, 2019, 11:10 AM), https://perma.cc/H844-RTUC. That some politicians, bureaucrats, and scholars wish to use the blunt force of antitrust to achieve their desired ends is unfortunate—but not new.36See, e.g., Alan Reynolds, The Return of Antitrust, 41 Reg. 24 (2018); Wright et al., supra note 2, at 294.

B. Scott Morton, Dinielli, & Their Roadmap

Scott Morton and Dinielli have now penned three “Roadmaps,” each of which relies on flawed preliminary analysis conducted by the United Kingdom’s Competition and Markets Authority (“CMA”).37Roadmap, supra note 16, at 2 (citing Competition & Markets Authority, Online Platforms & Digital Advertising: Market Study Interim Report (2019)). The CMA has since released its final report on competition in digital advertising, concluding that Facebook and Google dominate separate digital advertising markets and that their dominance harms consumers, including users and advertisers.38Competition & Markets Authority, Online Platforms & Digital Advertising Market Study Final Report 5 (July 1, 2020), https://perma.cc/PH23-4KWX [hereinafter CMA Final Report]. Relying on the report, the CMA has pleaded with the UK government for more power, including the ability to break up industries without having to abide by existing protections that ensure such an upheaval in the marketplace is justified.39Sam Bowman, The UK has Badly Missed the Mark on How to Regulate Big Tech, The Telegraph (July 3, 2020, 6:00 AM), https://perma.cc/HTE5-KZDL.

Even setting aside the fact that the CMA’s data and analysis are not focused on the United States, neither Scott Morton and Dinielli nor any government should rely on the CMA’s advertising reports—preliminary, final, or otherwise. Despite spanning hundreds of pages, the CMA’s reports are built on a foundation of sand.

For starters, the CMA report is untethered from actual antitrust doctrine. First, the CMA failed to uncover any actual harms. Instead, it merely speculates about how consumers “might” be worse off because of Big Tech.40See, e.g., CMA Final Report, supra note 38, at 69 (“In a more competitive market, consumers might not need to provide so much data in exchange for the services they value.” (emphasis added)); Id. at 180 (“The net effect in terms of consumer harm is that a large proportion of consumers may make decisions about platforms that they might not otherwise make—that is they may use platforms despite their concerns because they feel they have little choice.”(emphasis added)); Id. at 198 (“As we note above, from the evidence available to us, it is clear that few consumers engage with privacy policies on sign-up to platforms. We consider the same is likely to be true for consumer engagement with terms and conditions.” (emphasis added)); Id. at 201 (“As a result, it is likely that at least some consumers sign up to platforms and share data when they might not otherwise have done so had they been informed of the consequences.” (emphasis added)). Crucially, the report does not find that consumers actually are worse off. No wonder the CMA couches its “findings”—more accurately called hypotheses—in wishy-washy language: “could be” appears 91 times; “we believe” 27 times; and “might” 76 times.41The Author calculated these numbers by performing a key word search of the CMA’s final report. Although the CMA sometimes uses these words in a manner unrelated to its investigation or findings, the majority relate directly to the report’s bottom-line conclusions. Indeed, those phrases mirror what one might expect to see in a press release announcing the start of an investigation, not in a final report after a year-long process concludes. This is especially true given the stakes: breaking up some of the most successful companies in history.

Second, the report snubs antitrust analysis. To be sure, the CMA sees things differently. It contends that advertising prices are higher than they ought to be, which it takes as evidence of anticompetitive markets.42CMA Final Report, supra note 38, at 8 (“These costs are likely to be higher than they would be in a more competitive market, and this will be felt in the prices that consumers pay for hotels, flights, consumer electronics, books, insurance and many other products that make heavy use of digital advertising.” (emphasis added)). But the CMA fails to explain how it knows this. It doesn’t even bother to give a ballpark number on what prices would be in the hypothetical competitive market it constructed for the analysis it does not share with readers.43Instead, the CMA merely repeats time and again that prices would be lower if Google and Facebook competed in competitive digital advertising markets. See, e.g., CMA Final Report, supra note 38, at 314 (“[W]e have also shown that the weak competition in both search and display advertising allows the large platforms to exploit their market power by earning higher prices in the advertising market than would be expected in a more competitive market.”).

At the same time, the CMA dismisses most of the benefits Google and Facebook have brought to the digital advertising market. There is no mention of price reductions—which, in the United States amount to over forty percent since 2010.44Michael Mandel, The Declining Cost of Advertising: Policy Implications, Progressive Pol’y Inst. 2 (July 2019), https://perma.cc/GBU5-G834. It also gives no consideration to targeted advertising’s benefits, which allow small- and medium-sized businesses to reach consumers across the country.45See Top 26 Benefits of Facebook Advertising: How Facebook Ads Help!, Lyfe Marketing (July 29, 2019), https://perma.cc/66GD-82GP. For less money than ever before, these businesses no longer must rely on their local markets for consumers; now, they can reach consumers everywhere.46Mandel, supra note 44, at 13.

The CMA’s report and Scott Morton and Dinielli’s reports give shallow treatment to actual evidence. They ignore or downplay evidence of benefits to consumers while hyping speculative evidence of harm that accords more with their preferences than with consumers’. Their arguments boil down to: we know what consumer harms look like, we don’t see definitive evidence of those harms, but we have a hunch such harms exist, so we will speculate about those harms, and cast them as conclusions based on facts.

This Article, then, should be read as a rebuke of both Scott Morton and Dinielli’s Roadmap and the CMA’s final report. While they are scholars, not government officials, and while the CMA’s jurisdiction does not extend to the United States, their ideas are so far astray—so unglued from antitrust doctrine—that they must be called out for what they are: a return to “big is bad” no matter the evidence.

II. Primer on Antitrust Laws & Doctrines

Before jumping headfirst into the Roadmap’s analytical defects, it’s worth getting a feel for antitrust law and its doctrines. Although this Section will sound familiar to antitrust aficionados, much of its content is conspicuously missing from the Roadmap’s narrative.

A. Overview

Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890.47Wright et al., supra note 2, at 298. And it did so in response to mounting unrest brought on by the country’s rapid transformation into an industrial giant after the Civil War.48Wayne D. Collins, Trusts and the Origins of Antitrust Legislation, 81 Fordham L. Rev. 2279, 2282 (2013). This period witnessed factories displace farms, cities overshadow towns, and corporate America edge out local business.49See generally id. at 2281–87. But it was the great trusts of the day—the Standard Oils—that cast the darkest shadow over the country.50Wright et al., supra note 2, at 298. Their seemingly endless combinations and consolidations of industries stirred Congress to enshrine in law the country’s “national values of free enterprise and economic competition.”51N.C. State Bd. of Dental Exam’rs v. Fed. Trade Comm’n, 135 S. Ct. 1101, 1110 (2015).

But, like other national values, free enterprise and economic competition invited disagreement among Americans.52See Maurice E. Stucke & Ariel Ezrachi, The Rise, Fall, & Rebirth of the U.S. Antitrust Movement, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Dec. 15, 2017) (contrasting antitrust approaches from different eras), https://perma.cc/5XZP-Y2WL. It also bedeviled the US Supreme Court. In an early case, the Court severely narrowed the Sherman Act’s reach by exempting manufacturers, rendering most of the economy outside the bounds of the government’s enforcement power.53United States v. E. C. Knight Co., 15 S. Ct. 249 (1895). That controversial decision soon gave way to an antitrust doctrine that bobbed and weaved from one social concern to some other economic concern and back again. Along this zig-zagging path, the federal government was able to:

* “[P]revent ‘bigness,’ that is, to preserve the small, localized businesses that characterized early America”;54Wright et al., supra note 2, at 299.

* Protect “small dealers and worthy men” from their competitors even if doing so raised prices for consumers;55United States v. Trans-Mo. Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. 290, 323 (1897).

* Block “great industrial consolidations [because they] are inherently undesirable, regardless of their economic results”;56United States v. Aluminum Co. of Am., 148 F.2d 416, 428–29 (2d Cir. 1945). and

* Shield “viable, small, locally owned business” from competition even if that meant “higher costs and prices might result from the maintenance of fragmented industries and markets.”57Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 333, 344 (1962).

Ripped from any objective standard, these antitrust cases transmogrified a law meant to champion competition and protect consumer welfare into doctrines that shielded the status quo and handed out corporate welfare.

These were bad days for antitrust. As former Federal Trade Commissioner Joshua Wright put it, “[t]he result of this approach was that consumers were made worse off by preventing the very competition from which they would benefit and which the competition laws were supposed to promote.”58Wright et al., supra note 2, at 300. “In the name of defending helpless individuals,” he adds, “the Court decreased the purchasing power of individual consumers—by preserving inefficient firms with higher prices and lower output—and issued opinions that explicitly chose to foster corporate welfare over consumer welfare.”59Id. at 300.

Another problem: No one knew what conduct was permissible and what wasn’t. Without clear, objective standards for the government to apply equally, regardless of a business’s size, the business community was left to guess—and to litigate should the government decide that particular business was that year’s antitrust target.60Ryan Young, Antitrust Bascis: Rule of Reason Standard vs. Consumer Welfare Standard, Competitive Enter. Inst. (July 8, 2019), https://perma.cc/3TP9-DB3N. As Justice Potter Stewart of the Supreme Court once remarked: “The sole consistency that I can find is that in litigation under § 7 [of a related antitrust act], the Government always wins.”61United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270, 301 (1966) (Stewart, J., dissenting).

Once the consumer welfare standard entered the scene, however, antitrust improved. Today, antitrust focuses on promoting the benefits that come from national values like free enterprise and market competition62Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2290 (2018).: lower prices for consumers, lower costs for businesses, higher productivity for both, and greater innovation across the board.63Id.

And today, we know that antitrust laws are not meant to protect a business’s competitors but instead the competitive process. “The purpose of the [Sherman Antitrust] Act,” the Supreme Court has said, “is not to protect businesses from the working of the market; it is to protect the public from the failure of the market.”64Spectrum Sports, Inc. v. McQuillan, 506 U.S. 447, 458 (1993). And because “[c]ompetition is a ruthless process,” US antitrust doctrine tolerates aggressive conduct even when “[a] firm that reduces cost and expands sales injures rivals—sometimes fatally.”65Ball Mem’l Hosp., Inc. v. Mut. Hosp. Ins., Inc., 784 F.2d 1325, 1338 (7th Cir. 1986). In fact, even when a firm has monopoly power—what most people think of when they hear antitrust—the law applies only when that firm takes illegal steps to entrench its monopoly power.66Standard Oil Co. of N.J. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1, 10 (1911). In other words, monopolies are not, by themselves, illegal.

B. Sherman Antitrust Act § 2: Monopolies

Against this backdrop, this Article turns next to the Sherman Act’s text. Under section 2 of that law, no business may “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States, or with foreign nations.”6715 U.S.C. § 2. A business violates the law’s ban on monopolization only when it:

(1) Has durable monopoly power; and

(2) Uses exclusionary practices to obtain, maintain, or increase its monopoly power.68United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966).

1. Step 1: Show Monopoly Power

Monopoly power means a business has “the power to control prices or exclude competition” from the market.69United States v. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 351 U.S. 377, 391 (1956). Plaintiffs can show monopoly power through direct evidence that the defendant business charged prices significantly higher than what they would be if the relevant market were competitive.70See, e.g., Geneva Pharm. Tech. Corp. v. Barr Lab, Inc., 386 F.3d 485, 500 (2d Cir. 2004). More often, though, they rely on indirect evidence that shows a business:

(1) Has a large share of the relevant market it operates in; and

(2) Is protected by barriers to entry into that market.71See, e.g., Broadcom Corp. v. Qualcomm, Inc., 501 F.3d 297, 307 (3d Cir. 2007).

Monopoly power requires “something greater” than just mere market power.72See Eastman Kodak Co. v. Imagine Tech. Servs., Inc., 504 U.S. 451, 481 (1992). In other words, the defendant business’s market share must be relatively high. Plaintiffs thus have an incentive to define the market narrowly (fewer competitors, more dominance); defendants, the opposite (more competitors, less dominance). The Supreme Court has sought to avoid these subjective pitfalls by defining the relevant market as including the product or service at issue and anything “reasonably interchangeable” with it.73Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 325 (1962). Whether a product or service is reasonably interchangeable turns on whether a price increase for Product A would lead consumers to buy Product B instead.74Id.

Although the Supreme Court’s definition dates to 1962, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission—the plaintiffs in many monopoly cases—also use demand substitution to define the relevant market.75U.S. Dep’t of Justice & FTC, Horizontal Mergers Guidelines § 4 (2010). Their “hypothetical monopolist” test asks whether a monopolist would profit from imposing a “small but significant and non-transitory increase in price” (“SSNIP”) of about five percent on the product in question.76Id. If it would, then that is the relevant market; if not, then the market is expanded until buyers have no substitutes left.77Id.

But there’s a wrinkle in this case: Facebook is free. Although some lower courts have held that free products or services are exempt from antitrust enforcement,78See, e.g., Kinderstart.com, LLC v. Google, Inc., No. C-06-2057-JF(RS), 2007 WL 831806, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 16, 2007) (dismissing a section 2 complaint against Google Search because the service is free to consumers). some scholars79See, e.g., John M. Newman, Antitrust in Zero-Price Markets: Applications, 94 Wash. U. L. Rev. 49, 166–70 (2016). have argued that nonprice factors—for instance, personal data shared—can substitute for price. For purposes of this Article, the latter approach will be taken.

In any event, there is no magic number that declares dominance, but the Supreme Court has never found monopoly power when the market share is below seventy-five percent.80Kolon Indus., Inc. v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 748 F.3d 160, 174 (4th Cir. 2014). Some circuit courts have tried to flesh this analysis out with rebuttable presumptions: in the Tenth Circuit, the market share must usually be at least seventy percent;81Colo. Interstate Gas Co. v. Nat’l Gas Pipeline Co. of Am., 885 F.2d 683, 694 n.18 (10th Cir. 1989). in the Second Circuit, usually ninety percent;82United States v. Aluminum Co. of Am., 148 F.2d 416, 424 (2d Cir. 1945) (adding that 60–64% market share is “unlikely” to be sufficient). and in the Third, “significantly larger” than fifty-five percent.83United States v. Dentsply Int’l, Inc., 399 F.3d 181, 187–88 (3d Cir. 2005).

Numerical differences aside, the monopoly power must be durable.84See, e.g., id. at 188–89 (“[I]t is not market share that counts, but the ability to maintain market share.”); Colo. Interstate Gas Co., 885 F.2d at 695–96 (“If the evidence demonstrates that a firm’s ability to charge monopoly prices will necessarily be temporary, the firm will not possess the degree of market power required for the monopolization offense.”). Like with market dominance, there is no definitive proof indicating a business’s market share is enduring. But courts often look for evidence indicating barriers to entry—long-run costs new firms must pay that the defendant skirts—that would keep new competitors out of the relevant market.85LA Land Co. v. Brunswick Corp., 6 F.3d 1422, 1427–28 (9th Cir. 1993). Of relevance in the social media and social networking world are:

* Multi-Homing: Scott Morton and Dinielli (and others86Comm. for the Study of Digital Platforms, Market Structure and Antitrust Subcomm., Chicago Univ. Booth Bus. Sch. 18–21 (May 15, 2019) [hereinafter Study of Digital Platforms]. ) claim that consumers are unlikely to switch from one social media platform to another and are less likely to use both Facebook and other platforms.87Roadmap, supra note 16, at 12. They believe that it is too burdensome for consumers to make the switch because all of their content and contacts are housed on Facebook already.88Id. at 11. So as Facebook grows, more consumers become stuck on the platform, which in turn makes it difficult for a new competitor to attract users.

* Network Effects: Scott Morton and Dinielli (and others89Michael A. Cusumano et al., The Business of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, & Power 16 (2019).) likewise claim that social media platforms increase in value as they grow more popular.90Roadmap, supra note 16, at 11. The increase in users means an increase in content and contacts, which serves to attract even more users. The more people you know on Facebook, the more likely you are to join the site.

* Data Collection: Scott Morton and Dinielli (and others91Study of Digital Platforms, supra note 87, at 21–28.) also claim that because Facebook and its peers can collect user data, they are able to improve their products and services based on consumer insights others do not have, and are able to attract ever-increasing revenues from advertisers, who value the data as a tool to target ads.92Roadmap, supra note 16, at 18.

2. Step 2: Show Exclusionary Conduct

Even with this evidence in hand, plaintiffs are only halfway there. After the plaintiffs show monopoly power, they must show the defendant business acted in some exclusionary way to benefit its monopoly power.93United States v. Microsoft Corp., 253 F.3d 34, 58 (D.C. Cir. 2001). In other words, plaintiffs must show conduct indicating “the willful acquisition or maintenance” of monopoly power that cannot be explained by “growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.”94United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966). Distinguishing between illegal exclusionary conduct and legal competitive conduct requires analyzing harms to the competitive process itself.95Id. Common harms include predatory pricing,96Cargill, Inc. v. Monfort of Colo., Inc., 479 U.S. 104, 117 (1986). exclusive dealing,97Interface Group, Inc. v. Mass. Port. Auth., 816 F.2d 9, 11 (1st Cir. 1987). refusals to deal,98Aspen Skiing Co. v. Aspen Highlands Skiing Corp., 472 U.S. 585, 601 (1985). tying,99Int’l Salt Co. v. United States, 332 U.S. 392, 396 (1947). and the like.

III. Facebook Isn’t a “Near-Monopoly” or Anywhere Close to It

Section 2 of the Sherman Act, you’ll recall, makes it unlawful to “monopolize, or attempt to monopolize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons, to monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several States.”10015 U.S.C. § 2 (2018). Although section 2 creates three separate offenses,101The offenses include: (1) monopolization; (2) attempted monopolization; and (3) conspiracy to monopolize. only monopolization is relevant here. Under that offense, plaintiffs must prove both (1) “possession of monopoly power in the relevant market”; and (2) “the willful acquisition or maintenance of that power as distinguished from growth or development as a consequence of a superior product, business acumen, or historic accident.”102United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966).

Simply put, monopoly power is unlawful only when “accompanied by an element of anticompetitive conduct.”103Verizon Commc’ns Inc. v. Law Off. of Curtis V. Trinko, LLP, 540 U.S. 398, 407 (2004). According to Scott Morton and Dinielli, though, this is a difference that makes no difference: “Facebook,” they write, “has a monopoly in social media and/or social networks, whether considered in lay or legal or economic terms.”104Roadmap, supra 16, at 36. In support of this conclusion, they first point to Facebook’s seventy-five percent market share in the “communications-focused” social media market.105Id. at 9. Next, they give a laundry list of business decisions that are, from their vantage point, anticompetitive.106Id. at 20–29.

Neither argument can succeed. First, Scott Morton and Dinielli use the wrong market, which artificially inflates Facebook’s market share. And second, the businesses practices they cite as exclusionary are actually procompetitive.

A. Facebook’s Relevant Market

The first step is to define Facebook’s relevant market. At first glance, this task seems straightforward enough: Facebook is a social media platform, so the market must be social media platforms.

Yes and no. To begin with, Facebook is what economists call a “two-sided platform.”107See, e.g., Iakovos Sarmas, Market Definition for Two-Sided Platforms: Why Ohio v. American Express Co. Matters for the Big Tech, 19 Fla. St. U. Bus. Rev. 199 (2020). This means Facebook “offers different products or services to two different groups who both depend on the platform to intermediate between them.”108Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2280 (2018). In English, this means Facebook plays matchmaker between users and advertisers, and it competes for at least two different sets of customers. So, yes, Facebook competes in the social media platform market. But it also competes in the digital advertising market.

This follows from the rule that the market must include Facebook and all products or services that are “reasonably interchangeable” with it.109Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 325 (1962). Other products or services are reasonably interchangeable when customers have the “ability and willingness” to turn to them following a price increase or “non-price change such as a reduction in [Facebook’s] product quality or service.”110Horizontal Mergers Guidelines, supra note 76. Market definition is thus “focuse[d] solely on demand substitution factors.”111Id. at 76.

So, what is Facebook and what are its products or services? In its legally required SEC filings, Facebook describes itself as:

* “[B]uild[ing] useful and engaging products that enable people to connect and share with friends and family through mobile devices, personal computers, virtual reality headsets, and in-home devices”;112Facebook, Inc., supra note 25. and

* “[H]elp[ing] people discover and learn about what is going on in the world around them, enabl[ing] people to share their opinions, ideas, photos and videos, and other activities with audiences ranging from their closest family members and friends to the public at large, and stay connected everywhere by accessing [its] products.”113Id.

The products Facebook alludes to include114This list is not exhaustive; it merely recites the products Facebook chooses to highlight in its required legal filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission. On its website, Facebook lists other, less well-known products like Spark AR Studio and Audience Network. See “What Are the Facebook Products?” Facebook, https://perma.cc/UMJ4-LB5B.:

* Facebook: a platform that “enables people to connect, share, discover, and communicate with each other on mobile devices and personal computers. There are a number of different ways to engage with people on Facebook, including News Feed, Stories, Marketplace, and Watch.”115Facebook, Inc., supra note 25.

* Instagram: a separate platform that “is a place where people can express themselves through photos, videos, and private messaging, including through Instagram Feed and Stories, and explore their interests in businesses, creators and niche communities.”116Id.

* Messenger: a “messaging application for people to connect with friends, family, groups, and businesses across platforms and devices.”117Id.

* WhatsApp: a “secure messaging application that is used by people and businesses around the world to communicate in a private way.”118Id.

* Oculus: the company’s “hardware, software, and developer ecosystem [that] allows people around the world to come together and connect with each other through [Facebook’s] Oculus virtual reality products.”119Id.

From this bird’s-eye view, Facebook sounds a lot like a communications company. After all, its resume and product descriptions are chock full of industry buzzwords—“communicate,” “connect,” “messaging.” In fact, this language may have been on Wall Street’s mind when it recently revamped its Global Industry Classification System (the method used to match stocks with stock indexes) and bounced Facebook out of the “information technology” category into an expanded “communications services” category.120Lu Wang, It’s Official: Google & Facebook are Communications Companies, Bloomberg (Jan. 12, 2018), https://perma.cc/8988-4ZRG. In its new home, Facebook joins the likes of AT&T, Verizon, and Comcast, as well as the also reclassified Google, Twitter, Snapchat, Netflix, and Disney.121Noel Randewich, Facebook, Alphabet Shifted in Sector Classification System, Reuters (Jan. 11, 2018), https://perma.cc/TPP7-S793.

At first blush, this curious grouping may seem like Wall Street’s equivalent of the kitchen junk drawer. But with trillions of dollars on the line, the decision wasn’t made haphazardly; instead, it came after expert study of product and market evolution.122Id. As it turns out, though, one doesn’t need to be an expert to see what they see.

Think first of the broad similarities these companies share. In some form or another, each facilitates communication, distributes content, or does both. Now think of Facebook. As noted, the company’s products undeniably facilitate communication. But they also all distribute or help distribute content. Facebook lets users share and interact with user-made content (photos of the family vacation, videos of the new puppy, posts about almost everything), as well as content from third parties (a link to a GoFundMe page, a news clip from CNN’s Facebook page). Instagram likewise lets users do the same. For most people none of this is groundbreaking news—under the (unofficial) American Common Sense Classification System, Facebook is simply known as a social media platform.123“Social media platform” is often used interchangeably with “social network.” See, e.g., Dina Srinivasan, The Antitrust Case Against Facebook: A Monopolist’s Journey Towards Pervasive Surveillance in Spite of Consumers’ Preference for Privacy, 16 Berkeley L.J. 39, 40 (2019) (calling the relevant market “social network” and Facebook as “the reigning platform” in it); Roadmap, supra note 16, at 5–7 (separating “Social Media Sector” from “Online Social Networks” but still describing Facebook as a “social media platform[],” “social network,” and “social network platforms”).

But there is an important difference between the companies—their revenue streams. AT&T, Verizon, Comcast, Netflix, and Disney all have subscription-based services.124Reuters, Netflix Shares Drop After Verizon Reveals Disney Streaming Promotion, N.Y. Post (Oct. 22, 2019), https://perma.cc/5DC3-MWR9. In other words, users must pay to hit “play” or “send.” Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, and Google, on the other hand, are free for users to use. To be sure, advertising revenue is neither unique to these platforms nor shunned by their subscription-based peers. In fact, some offer multitiered subscription packages that offer lower prices on subscriptions but with more advertisements on their platform.125For example, Hulu, which is owned by The Walt Disney and Comcast Corporation, offers multiple subscription plans: basic Hulu costs $5.99 per month and displays ads; Hulu (No Ads) costs $11.99 per month and displays no ads. See Hulu, What Are the Costs & Commitments for Hulu? (May 29, 2020), https://perma.cc/X9EB-7NXY.

Free-to-use platforms rely so heavily on advertising, however, that they are said to have two sets of consumers: users and advertisers. As mentioned, because Facebook provides services to both, and thereby enables interactions between them, it is a two-sided market.126See Roadmap, supra note 16. Two-sided markets usually have direct or indirect network effects.127See id. Direct network effects occur when a product’s value increases with the number of people using it.128See id. Indirect network effects, on the other hand, occur when the product’s value to one group increases the more another group uses it.129See id.

In plain terms that means Facebook operates in distinct, though overlapping, markets at the same time. First, it competes for users in the social media market. And second, it competes for advertisers in what’s known as the digital display ads market. Facebook’s legal filings recognize this too: “We compete with companies that sell advertising, as well as with companies that provide social, media, and communication products and services that are designed to engage users on mobile devices and online.”130Facebook, Inc., supra note 25.

Why does any of this matter? Well, if Facebook is a two-sided market with direct network effects, then the relevant market must be defined so as to include both Facebook’s social media market and its digital display market.131See Ohio v. Am. Express Co., 138 S. Ct. 2274, 2280 (2018). But if Facebook has only indirect network effects, it may not be necessary to combine the markets.

Scott Morton and Dinielli assume the latter. They note early on that Facebook has “at least two types of customers,” and that advertisers “may have a location to display ads that is a substitute for social media.”132Roadmap, supra note 16, at 6. But without much explanation, Scott Morton and Dinielli analyze Facebook as having only indirect network effects. This is a curious decision given statements they make throughout their report. In their section about entry barriers, for example, Scott Morton and Dinielli note that Facebook has strong “network effects,” explaining that the platform’s value increases the more users who use it.133See id. at 15. They note also that Facebook’s value to advertisers increases with more users.134See id. at 19.

To be sure, Facebook may not have direct network effects. Although Facebook’s value to advertisers undoubtedly increases with the number of users who use the site (a bigger audience for them to reach), it is not entirely clear whether the same is true for users. As Scott Morton and Dinielli point out, Facebook’s value to users may even decrease as the number of ads increase.135See id. at 35. Fair enough. But that really makes sense only if users must know the “how” or “why” behind Facebook’s business decisions in order to benefit from them. As a general matter, Facebook grows more valuable to users the more Facebook improves and innovates its products. Because Facebook’s revenue comes almost entirely from advertising revenue, ads are what fuel the company’s efforts to improve the user experience.136Trefis Team, What is Facebook’s Revenue Breakdown?, Nasdaq (Mar. 28, 2019), https://perma.cc/7EJ4-ULKX. They also allow Facebook to remain free for users.137Greg DePersio, Why Facebook is Free to Use (FB), Investopedia (Dec. 3, 2015), https://perma.cc/7LBQ-UTE9. So although users may not know how advertisers benefit them, or why more ad revenue for Facebook can benefit them, they would feel the adverse effects if ads declined.

Because it is likely that Facebook has direct network effects, the relevant market must integrate the markets for social media platforms and digital display advertising. Here, there can be little doubt that Facebook is not a monopoly. Not only does Facebook compete against platforms like Twitter and Snapchat, it also competes against Google, Amazon, and a whole host of other platforms that place ads on their sites.138See Marchese, supra note 18, at 11–12; Lauren Feiner, Facebook and Google’s Dominance in Online Ads is Starting to Show Some Cracks, CNBC (Aug. 2, 2019), https://perma.cc/NV7E-Y4S4.

But even if Scott Morton and Dinielli are right that Facebook has only indirect network effects, the company is not a monopoly in either the social media or digital advertising market. Twitter, Snapchat, YouTube, and newcomer Parler—to name but a few—all compete with Facebook in the social media market. And, as just mentioned, Google, Amazon, and others all compete with Facebook in the digital advertising market.

Scott Morton and Dinielli try to circumvent this reality. Although they concede that Facebook operates in the social media market, they go on to define the relevant market so narrowly that their definition might as well be “Facebook and only Facebook.” In their telling, social media platforms “differentiate themselves from one another in various ways,” which means they actually occupy distinct markets.139Roadmap, supra note 16, at 6. One market includes “content-focused” platforms that “facilitate the distribution and consumption of content.”140Id. at 6–7. Here, they lump YouTube and TikTok together because their content “can be enjoyed by users with a wide range of relationships to the person posting, including complete strangers.”141Id. at 6. That distinction doesn’t even make sense: like Facebook, TikTok, YouTube, Snapchat, and many others all allow public and private postings.

The other market includes “communication-focused social networks.”142Id. This, we’re told, is where Facebook belongs because it “primarily facilitate[s] communication (including the sharing of third-party content) among groups of friends who choose each other and enjoy content in large part because of those relationships.”143Id. But even under this narrow definition, Facebook still faces competition from Snapchat and Twitter.144See CMA Final Report, supra note 38, at 122.

Here, any difference actually makes no difference. First, Scott Morton and Dinielli’s justification underscores that these platforms all operate in the same market. Why would the platforms need to “differentiate themselves from one another”—in one way or “in various ways”—if they didn’t compete against each other? Second, any validity the distinction between communication-focused and content-focused platforms may once have had no longer exists. As Scott Morton and Dinielli and the CMA point out, social media has blurred the lines between video sharing, messaging, blogging, and other services.145Roadmap, supra note 16, at 5. Their Roadmap implicitly acknowledges that Facebook is just as much about content as it is about communication. As discussed later, the Roadmap is full of criticisms about the content users see on Facebook’s platform.146See infra Part IV. Scott Morton and Dinielli go so far as to paint Facebook as parading increasingly harmful content before users to keep them engaged and ad revenue flowing.147Roadmap, supra note 16, at 5.

In fact, the relevant market is probably even larger than just social media platforms. As Scott Morton and Dinielli unwittingly prove elsewhere in their paper, the relevant market should include all websites that compete for users’ attention.148See infra Part IV.B. After all, logic suggests that advertisers run ads on Facebook precisely because they expect Facebook users to see those ads. It therefore follows that if those users are on other websites, then those websites compete with Facebook (and its advertisers) for users’ attention.

So, it seems that Scott Morton and Dinielli are trying to have their cake and eat it too. As they would have it, Facebook is conveniently a communications-based platform when it comes to defining the relevant market. But when it comes to consumer harms, it is a content cesspool. To be sure, Facebook could be a communications platform that also contains harmful content. But that observation serves only to further weaken their arbitrary dividing line—if anything, it shows that Facebook is both communication and content focused.

Regardless of Scott Morton and Dinielli’s intent, their market definition ignores market realities. Facebook and its competitors have all evolved since their launch dates—a fact reflected in Wall Street’s decision to group these companies under the umbrella of “communication services.”149Wang, supra note 121. They also assume, without justification, that social media is static, that tomorrow’s platforms will look, feel, and act largely like today’s do. But it’s exactly that kind of thinking that led analysts, scholars, and the press to believe that Yahoo! Search was so dominant that it would never be beat.150Keegan, supra note 31. Ditto for MySpace.151Id.

In short, Facebook is a two-sided platform that must compete for users and for advertisers. Thus, at its broadest, Facebook’s relevant market is the “attention” market; at its narrowest, it’s social media. Whether it has direct or indirect network effects, and whether defined as a social media platform or a communications-based platform, Facebook still faces competition.

B. Market Share

With the contours of Facebook’s relevant market defined, we turn next to its market share. As you’ll recall, the Supreme Court has never found monopoly power when a company’s market share is below seventy-five percent.152Kolon Indus., Inc. v. E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 748 F.3d 160, 174 (4th Cir. 2014). Fortuitously, Scott Morton and Dinielli’s analysis of Facebook’s market share happens to be exactly seventy-five percent.153Roadmap, supra note 16, at 9. But, like their definition of the relevant market, their analysis of Facebook’s market share is a game of analytical Twister.

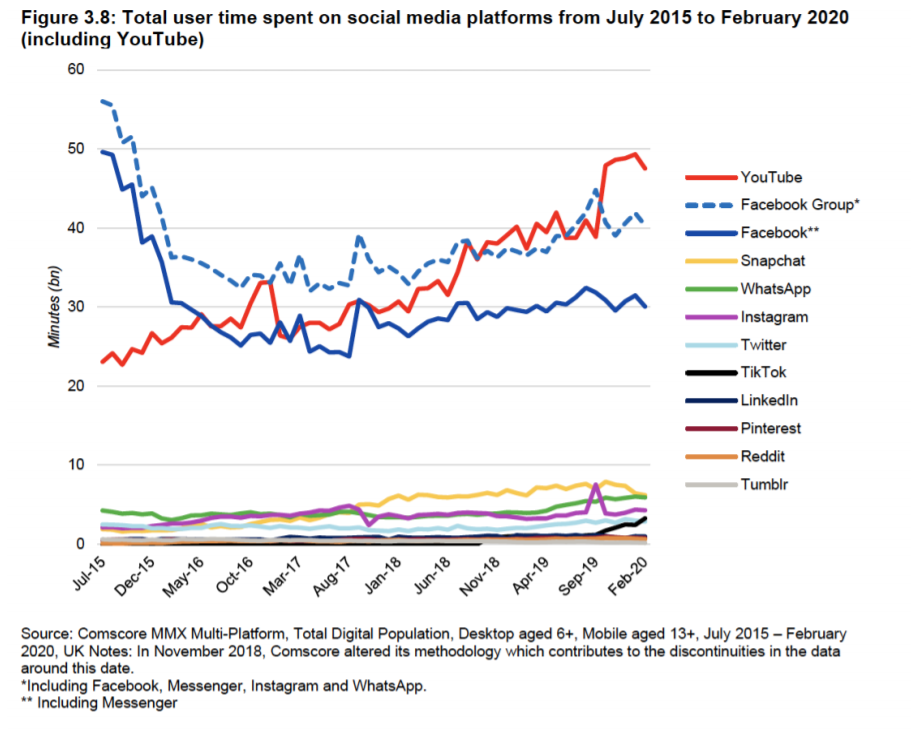

First, a note about Scott Morton and Dinielli’s methodology. In traditional markets, market share is typically calculated by comparing a company’s sales (or the value of those sales) to all sales in the relevant market for a single year.154Jonathan Baker, Market Definition: An Analytical Overview, 74 Antitrust L.J. 129, 129 (2007). But because Facebook operates in a two-sided market and because it is free for users, another method is needed. So, Scott Morton and Dinielli and the CMA calculate market share based on the number of minutes a user spends on a particular platform divided by the number of minutes the user spends on social media in total.155Roadmap, supra note 16, at 9. They justify this metric on the grounds that companies “want to keep eyeballs on their platforms for as long as possible in order to sell more ads.”156Id.

This observation about a platform’s business model reinforces that Facebook operates in an integrated, multi-sided market. As a practical matter, the relevant market is broadly about attention—Facebook and other platforms all compete for users’ attention, which is what they sell to advertisers.157See David S. Evans, Attention Rivalry Among Online Platforms, 9 J. Competition L. & Econ. 313 (2013); David S. Evans, The Economics of Attention Markets (Apr. 15, 2020) (unpublished manuscript), https://perma.cc/C7S3-RSR6. One way of keeping users’ attention is by making it as easy as possible for them to visit the platform—by, say, making it free to use. And although large financial outlays to attract and maintain customers are not unheard of in business, it is often unsustainable in the long-term. Thus, Facebook depends on advertisers for revenue to keep its platform attractive to users, and users keep the platform attractive to advertisers.

This feedback loop reveals that Facebook’s rivals are, at least, other online businesses that draw user attention through free products or services and that rely on digital advertising. Because user time is a scarce good—everyone alive gets the same twenty-four hours in a day—any time spent on another website is time not spent using Facebook’s products.

Second, given this reality, the market must include all social media platforms that operate like Facebook does. So, for example, Facebook’s share of user attention would be compared to that of Pinterest, Twitter, TikTok, Snapchat, YouTube, and other platforms. Scott Morton and Dinielli, however, define the market narrowly and exclude YouTube, even though it’s one of Facebook’s largest competitors for user attention and digital display advertisers.158Roadmap, supra note 16, at 9. With that competitor gone, Scott Morton and Dinielli peg Facebook’s market share—in the United Kingdom, remember—at seventy-five percent.159Id. To arrive at this number, they added Facebook’s, Instagram’s, and WhatsApp’s market shares together.160Id.

Catch all that? First, Scott Morton and Dinielli choose a metric—eyeballs on ads—that directly undercuts their narrowly defined market. Unfazed by this bait and switch, they plow ahead with their formula—subtract YouTube, add a heaping of Facebook-owned products, and voila, seventy-five percent market share!

This makes little sense. If YouTube, which competes with Facebook for advertising dollars is out, then why is WhatsApp, which doesn’t run ads, in? And how is Instagram more communication based than content based? Even worse, Scott Morton and Dinielli aren’t even using market shares for the right year. The CMA’s own chart, which is reproduced below, shows that Facebook—even when all its products are combined—has seen a dramatic decline in market share since 2015.161CMA Final Report, supra note 38, at 120. And looking at one year, the chart shows that Facebook’s combined market share hovers around forty percent.162Id. Regardless, the CMA’s own chart shows that Facebook’s market share is not durable; it’s down twenty percent since 2015.163Id. In other words, even if Scott Morton and Dinielli are right that Facebook is dominant, that dominance is not durable.

Perhaps recognizing that this formula is too removed from common sense, Scott Morton and Dinielli try to buttress their finding. Their additional points include:

* Citing the CMA’s finding that the market gained only two new competitors—Snapchat and Instagram—over the last few years;164Roadmap, supra note 16, at 9. and

* Claiming that no competitor “has achieved significant market share.”165Id. at 9.

Even under their narrowly defined market, the first point is not sound. Microsoft’s LinkedIn has seen massive growth;166Andrew Hutchinson, LinkedIn’s up to 690 Million Members, Reports 26% Growth in User Sessions, Social Media Today (Apr. 30, 2020), https://perma.cc/Y4KN-9RDH. so, too, with the newly launched Parler platform.167Jefferson Graham, Done with Facebook? Consider MeWe, Parler or Old Standbys such as LinkedIn, USA Today (last updated July 4, 2020) (“The app, which has been called the ‘Twitter for conservatives,’ is on a roll thanks to the presence of the politicians, and has grown to 1.5 million members from 1 million in just a week, the company recently told CNBC.”), https://perma.cc/U9PE-QPBL. And under a properly defined market, TikTok must be added to the list. The second point also misses the mark. Even if that were true, antitrust law doesn’t require competitors to achieve “significant” market shares to count as competitors.168What matters is whether the competitor’s product or service is reasonably interchangeable with the defendant business’s product or service. See Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 333, 325 (1962); Horizontal Mergers Guidelines, supra note 76.

Next, Scott Morton and Dinielli note that “[m]any people use more than one social network,” which is called “multi-homing.”169Roadmap, supra note 16, at 12. That’s certainly true. But they contend that this supports, rather than undermines, their argument that Facebook has a “near” monopoly on social media.170Id. at 11. For proof, they cite these statistics:

* Ninety-seven percent of Instagram’s users visit Facebook but only sixty-six percent of Facebook’s users visit Instagram;171Id. at 12.

* Ninety-five percent of Snapchat users visit Facebook, but only sixty-eight percent of Facebook’s visit Snapchat;172Id. and

* Seventy percent of TikTok users visit Facebook.173Id. at 13.

These statistics, we’re told, “confirm” that Facebook is “likely to have market power,” and that because TikTok’s users, who “skew young,” still use Facebook, users “do not view this platform as a substitute for Facebook.com.”174Id.

But these statistics, picked by Scott Morton and Dinielli themselves, reveal that Facebook does not have a near monopoly on social media. Instead, they show that a majority of Facebook’s users use other social media platforms, which seems to undercut their narrative that Facebook holds an undue sway over users’ attention. And although the multi-homing rates may not be perfectly reciprocal, they don’t have to be. Indeed, there are many reasons the proportion is not one to one—and none of them reflects anticompetitive or illegal behavior. For example:

* As Scott Morton and Dinielli note, TikTok’s users “skew young[er]” than Facebook’s users.175Roadmap, supra note 16, at 13. So if these users want to keep in touch with older relatives, they might turn to Facebook for that sole purpose.

* TikTok is also, as Scott Morton and Dinielli note, “the new kid on the block,” whereas Facebook opened to the general public in 2006.176Although Facebook launched in 2004, it was originally limited to select colleges and universities. It did not open to the general public—defined as anyone who was at least thirteen years old and had an email address—until 2006. Perhaps like Facebook in its early years, TikTok is embraced first by the young and later adopted by older users too.

* The same variables apply to Snapchat. It’s been around since 2011, and seventy-three percent of 18- to 24-year-olds use it, but only nine percent of 50- to 64-year-olds do.177Jenn Chen, 2020 Social Media Demographics for Marketers, Sprout Social (May 5, 2020), https://perma.cc/78AJ-652Y. By contrast, sixty-eight percent of the latter group use Facebook but only fifty-one percent of the younger group do.178Id.

Generational differences are worthy of elaboration. Facebook is popular among all age brackets, but it is most popular among those aged 18 to 29 and 30 to 49; it is least popular among those over 65 and under 18.179Id. With these facts in mind, we can observe the following:

* Someone who is 29 today would have been 15 when Facebook launched in 2006. Back then, the only other major social media platform was MySpace, which was then thought to be so dominant that Facebook stood no chance.180Keegan, supra note 31.

* Today, someone who is 15 can choose between or among Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat—to name just a few.

For added context, remember that Facebook launched during President George W. Bush’s second term; TikTok launched in the United States in 2018.181Paige Leskin, Inside the Rise of TikTok, the Viral-Video Sharing App that US Officials are Threatening to Ban Due to its Ties to China, Bus. Insider (July 13, 2020), https://perma.cc/MCJ9-E5KH. Facebook allows for the sharing of political content; TikTok intentionally limits political content.182Community Guidelines, TikTok (last updated Jan. 2020), https://perma.cc/4NYF-VL84. TikTok had around 20 million monthly users in late 2018; it boasts more than 65 million today.183Brandon Doyle, TikTok Statistics: Updated July 2020 (last updated July 13, 2020), https://perma.cc/BRZ8-QJPU. Based on these data points, we can speculate that perhaps TikTok is more popular than Facebook with young Americans because it’s new (and therefore intriguing) or because it’s not saturated with political content. And maybe TikTok is less popular among older Americans precisely because it’s new (and therefore relatively unknown or not appealing) and not saturated with politics.

Put simply, different generations of Americans have different tastes. It is thus unremarkable that rates of reciprocity are uneven—and, in fact, that suggests competition in the marketplace. If everyone used all social media platforms in equal proportion, then no platform would have as strong an incentive to innovate. Instead, TikTok has every incentive to eat into Facebook’s market share and to win over older Americans while cementing its popularity among the young. Conversely, Facebook must remain attractive to older Americans and try to compete with TikTok for younger ones.

To state the obvious, younger Americans are future consumers. Facebook must therefore win them over, or risk dissolving into irrelevancy. To be sure, younger Americans may switch to Facebook as they age. Perhaps they will come to desire more political content once they graduate high school. Or perhaps they’ll use Facebook solely for the purpose of reading political content while keeping TikTok as their main social media platform. Or maybe they’ll use Facebook, TikTok, Twitter, and other platforms for different purposes.

Whatever they may do, it is wrong to believe that social media platforms must resemble Facebook in order to be viewed as an alternative to Facebook. Scott Morton and Dinielli argue that although the market for social media includes platforms like YouTube, Facebook’s relevant market is actually narrower than that—it includes only “communication-focused” platforms that are, in all relevant respects, like Facebook. That narrow focus wrongly assumes, however, that American consumers view Facebook as the preferred “model” for social media. Seen this way, Facebook is of course going to dominate the market, just as Apple would be seen as dominating the smartphone market if we defined that market by features unique to iPhones.

Scott Morton and Dinielli also argue that a

significant reason that Facebook has market power is that a user cannot change platforms and expect to be able to stay in contact with her friends. Because social networks are not compatible, a user’s friends would have to change platforms with her for her to be able to continue to see their feeds.184Roadmap, supra note 16, at 11.

That observation is true only if one defines “stay in contact with her friends” to mean “to stay in contact with her friends in exactly the same way as they stayed in contact on Facebook.” As a practical matter, it is true that if a user left Facebook, she would, well, leave Facebook. But why Facebook’s unique features should be available on Facebook’s competitors’ platforms is never explained. And, as it were, Americans don’t necessarily want social media to resemble Facebook. The mere existence of “multi-homing” suggests Americans don’t rely solely on Facebook for their social media needs, nor wish to confine themselves to Facebook even if it is the largest platform.

Scott Morton and Dinielli also give Facebook more credit than it deserves; indeed, they discount factors outside Facebook’s control. For many Americans, especially older Americans, Facebook is familiar. Given the ever-evolving nature of social media platforms, older demographics may use Facebook simply because they know it best. That’s not a result of any anticompetitive behavior; that’s just good luck from timing.

Facebook is also an old platform, at least relative to its competitors. Again, this timing probably matters: Generation Z came of age with many social media platforms, including TikTok, which is dominant among that demographic.185Doyle, supra note 184. By contrast, Millennials, Generation Xers, and Boomers all started using social media when Facebook was not only new but really the only option.186See Keegan, supra note 31. Their sustained use of the platform is probably driven in part by comfort, convenience, and familiarity.

That some platforms focus heavily on certain forms of communication—like photos or videos—and Facebook offers more diversity does not mean Facebook represents what social media will look like in two, five, or ten years. Instead, it means that Facebook has a model that works for most of its current users. The key will be whether Facebook is able to attract new, younger users—and so far, it has been less successful.187See Mary Hanbury, Gen Z Says Facebook is the Number One Social-Media Platform They’ve Abandoned, Bus. Insider (July 8, 2019), https://perma.cc/NB44-9YB4; Matt Rosoff, Facebook Exodus: Nearly Half of Young Users Have Deleted the App From Their Phone in the Last Year, Says Study, CNBC (Sept. 5, 2018), https://perma.cc/6NN4-4PZZ.

So, if we were to follow Scott Morton and Dinielli’s assumptions, we’d calcify the social media market such that all options more or less looked like Facebook. That may be fine for many consumers, but the clear majority of Americans like the variety they have now. In any event, Facebook does not have dominant market share, let alone monopoly power.

C. Evidence of Monopoly Power

1. Direct Evidence

No matter the size of a company’s market share, plaintiffs must still prove that the defendant business has monopoly power.188Eastman Kodak Co. v. Imagine Tech. Servs., Inc., 504 U.S. 451, 481 (1992). One way of doing that is through direct evidence that shows a company charges prices far and above what a competitive market would support.189See, e.g., Geneva Pharm. Tech. Corp. v. Barr Lab, Inc., 386 F.3d 485, 500 (2d Cir. 2004). Scott Morton and Dinielli allege two pieces of direct evidence to show Facebook has monopoly power: (1) “social networks have strong direct network effects”; and (2) “Facebook has a near-monopoly share and enormous reach.”190Roadmap, supra note 16, at 11. Because Facebook is free for users, Scott Morton and Dinielli substitute qualitative factors like privacy protections and content type for price.191Id.

Turning to their first argument, Scott Morton and Dinielli claim that “[a] very significant reason that Facebook has market power is that a user cannot change platforms and expect to be able to stay in contact with her friends.”192Id. Their logic boils down to this: social media platforms lack interoperability, which deters users from abandoning Facebook, which forces users “to put up with Facebook’s fake news, or exploitation of privacy, or any other increase in quality-adjusted price.”193Id. Scott Morton and Dinielli further allege that these costs compound when the users looking to leave are members of a large group—if one member refuses to switch, he can block the group’s move.194Id.

That would be news to the nine percent of Americans who deleted their Facebook accounts in 2018,195Lynne Anderson, Why People Leave Facebook—And What it Tells Us About the Future of Social Media, The Conversation (last updated Jan. 8, 2020), https://perma.cc/K277-LUCV. the thirty-five percent who reported using the site less and less,196Id. and the forty-nine percent of young Americans who forgo Facebook altogether.197Chen, supra note 178. Those who left the site entirely gave several reasons similar to Scott Morton and Dinielli’s suggestions, including the Cambridge Analytica scandal, the site’s echo-chamber nature, and the desire to be more productive—in other words, they were not forced to put up with anything.198Anderson, supra note 196.

Plus, Facebook already lets users export their data, including a list of their friends. Scott Morton and Dinielli highlight a user’s Facebook contacts as the most valuable asset on Facebook,199Roadmap, supra note 16, at 11. so this criticism seems misplaced. But to the extent that the list may not match another platform’s—for example, a friend that goes by one name on Facebook and another on Twitter—that is a problem not easily remedied by Facebook. Indeed, if Facebook were to allow users to export detailed identifying data on a user’s friends, Scott Morton and Dinielli would likely criticize the move as hurting user privacy.

Speaking of user privacy, Scott Morton and Dinielli’s quality adjusted price arguments are too subjective to use as proof of direct evidence. To be sure, US antitrust doctrine recognizes that nonprice factors can stand in for price increases.200Horizontal Mergers Guidelines, supra note 76 (citing, for example, decreases in quality as a non-price factor). But Scott Morton and Dinielli do not make the case that fake news and privacy policies are such costs, let alone that they are above market level.

Take fake news first. Scott Morton and Dinielli cite it as a harm so widely understood as an objective harm that it needs no elaboration. But their discussion of fake news does not enjoy the widespread understanding that Scott Morton and Dinielli seem to take for granted: Republicans and Democrats don’t even agree on the definition of fake news.201See Mark Epstein, Memo to the New York Times: Definitions of “Fake News” Are Subjective, Nat’l Rev. (Dec. 23, 2016), https://perma.cc/AVE5-6VJL. Even if there were a common definition, many instances of fake news are in the eye of the beholder—what is fake to some is another’s alternative facts and is another’s reality. Practical problems aside, some users may also believe that, consistent with values of free speech, it is better for Facebook to allow more speech than less speech. Whatever the case may be, fake news is not objective enough to qualify as a cost forced down users’ throats.

The same is true of alleged privacy concerns. Polling reveals that Americans are worried about their digital privacy,202Greg Sterling, Nearly all Consumers are Concerned About Personal Data Privacy, Survey Finds, MarketingLand (Dec. 4, 2019), https://perma.cc/3G7Q-CTXS. and reports show that Facebook has responded by giving users more control over their data privacy.203See, e.g., Audrey Conklin, Facebook Gives Users More Control Over “Off-Facebook” Activity Tracking, Fox Bus. (Jan. 28, 2020), https://perma.cc/9X69-9R92; Sarah Perez, All Users Can Now Access Facebook’s Tool for Controlling Which Apps and Sites Can Share Data for Ad-targeting, TechCrunch (Jan. 28, 2020), https://perma.cc/545Y-VFME; Reuters, Facebook to Give Users More Control Over Personal Information, CNBC (last updated Mar. 28, 2018), https://perma.cc/LE8Q-SMYD. If Facebook had monopoly power, it would not need to respond to these concerns at all. Plus, privacy operates on a sliding scale—some users want total privacy well others are content with sharing some or all data in return for free services.

2. Indirect Evidence

Plaintiffs may also show monopoly power through indirect evidence of entry barriers. Scott Morton and Dinielli provide many reasons why Facebook is protected from competition.204See Roadmap, supra note 16, at 15–19. But these arguments fare no better.

First, Scott Morton and Dinielli claim network effects are a “significant” barrier to entry for new firms.205Id. at 16. Network effects, you’ll recall, occur when a product’s value grows proportionally with the number of people who use it.206See supra Part III.A. Some scholars, including Scott Morton and Dinielli and the CMA, believe that when a platform’s network effects “tip”—meaning, it has so many users that it becomes the default and only real option for users—the market closes its doors to new entrants.207Roadmap, supra note 16, at 16.

At best, this is an unproven-but-possible problem. To date, there is no empirical evidence that social media platforms have “tipped.”208David S. Evans & Richard Schmalensee, Debunking the “Network Effects” Bogeyman, 40 Reg. 36, 39 (Mar. 28, 2018). But there is evidence that it does not currently plague the market. Just this year, for example, a start-up platform called Parler entered the market and immediately attracted millions of new users—many of them conservatives who feel Facebook, Twitter, and other platforms moderate too strictly.209Graham, supra note 168. TikTok, meanwhile, entered the market in 2018 and is now the most popular app among young Americans.210Doyle, supra note 184.

What’s more, only fifty-one percent of young Americans use Facebook,211Chen, supra note 178. but supermajorities of them use other platforms like Snapchat and TikTok.212See id.; Doyle, supra note 184. If the network effects posed an actual barrier to entry, we’d at least expect to see these young consumers use both Facebook and its competitors—indeed, Scott Morton and Dinielli claim that because Americans more broadly use other platforms and Facebook, that’s proof of Facebook’s monopoly.

Second, Scott Morton and Dinielli claim that Facebook makes it difficult to multi-home because it does not offer full API access to all its competitors.213Roadmap, supra note 16, at 24. This argument is false. Facebook makes its API accessible to competitors and is used by direct competitors such as Tinder, Viber, TikTok, Zoom, and Pinterest.214Assoc. Press, Facebook’s Software Kit to Blame for Popular Apps Crashing, Spectrum News (Jul. 11, 2020), https://perma.cc/3VRS-6CRQ.

This argument also falls apart under common sense. Americans multi-home all day: many check Twitter, Instagram, TikTok, Pinterest, and Reddit regularly. Even Scott Morton and Dinielli acknowledge this. As they report, many Americans use multiple digital platforms.215Roadmap, supra note 16, at 16 (“Despite the fact that many consumers ‘cross-visit’ between different platforms, as described above, doing so is not necessarily easy.”).

Their complaint, however, is that multi-homing is not “necessarily easy.”216Id. In support of this, Scott Morton and Dinielli again cite the alleged lack of inoperability; this time claiming that Facebook does not allow users of products other than its own to simultaneously post content on another platform and on Facebook’s platforms.217Id. at 25. Of course, as they recognize, this is in part “intrinsic to the fact that most platforms are, indeed, run independently from one another.”218Id. at 17. Part of that independence includes content-moderation policies. Facebook may think that such simultaneous posting could cause more headaches than it is worth. Two points jump to mind. First, Facebook already has billions of pieces of content to worry about. Adding even more, especially when the platform is already under scrutiny from the left and right, would likely require the platform to hire even more employees to review flagged content and handle disputes. Second, it could lead to even more politicized attacks. Suppose someone’s tweet posts on Twitter and Facebook, but Twitter removes it for violating its policy. If Facebook decides not to remove the content from its platform, it will surely invite even more criticism from certain corners. The same is true in reverse.

Facebook also works with third parties to help them use its APIs in ways that respect users’ expectations.219Facebook for Developers: Facebook Platform Policy, Facebook, https://perma.cc/S6XX-9CWR. Despite Scott Morton and Dinielli’s claim to the contrary,220Roadmap, supra note 16, at 24. thousands of publishers, websites, and competitor platforms have access to the site’s APIs.221See Devin Coldewey, Facebook is Shutting Down Its API for Giving Your Friends’ Data to Apps, TechCrunch (Apr. 28, 2015), https://perma.cc/EZ5F-L7HT. But even if that were not the case, Scott Morton and Dinielli do not explain why Facebook must share its technology with its competitors. Facebook is not an essential facility, even if they believe that it is.

Third, Scott Morton and Dinielli claim Facebook’s data collection and use practices gives it a massive leg-up on its advertising competitors.222Roadmap, supra note 16, at 18. Data is neither finite nor incapable of being shared with one entity at any given time. In other words, Facebook may have data useful to its advertisers, but that data is not Facebook’s alone. Indeed, as Scott Morton and Dinielli reported in their first Roadmap, Google also has useful data for advertisers to capitalize on.223See, e.g., Fiona M. Scott Morton & David C. Dinielli, Roadmap for a Digital Advertising Monopolization Case Against Google, Omidyar Network 3 (May 2020), https://perma.cc/Y4RU-32QK. So, too, with Amazon. Both Google and Amazon are Facebook’s largest competitors in the digital advertising space.224Marchese, supra note 18, at 12.