Introduction

Courts have many interpretive tools to help construe statutory text that is found to be less than clear. One such tool is the rule of lenity. A typical formulation for the rule of lenity is that an ambiguous criminal statute should be strictly construed in favor of the criminal defendant and against the government.

The rule of lenity is a common law concept with deep historical roots. In England, it has existed for centuries.1See Sarah Newland, Note, The Mercy of Scalia: Statutory Construction and the Rule of Lenity, 29 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 197, 200–01 (1994); see also Johnson v. United States, 135 S. Ct. 2551, 2567 (2015) (Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment) (noting the rule of lenity “first emerged in 16th-century England”). In this country, the US Supreme Court wrote in 1820 that the rule “is perhaps not much less old than construction itself,” and reflects the “plain principle” that “[i]t is the legislature, not the Court, which is to define a crime, and ordain its punishment.”2United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. 76, 95 (1820) (emphasis omitted). Supporters state the rule of lenity furthers due process notice and fairness requirements, ensures that criminal laws are the product of the political process, encourages statutory clarity, and advances the rule of law, federalism, and states’ rights concepts, along with other noble goals.3See, e.g., United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931, 952 (1988); 3 Sutherland on Statutory Construction § 59:4 (7th ed. 2017); Nicholas Quinn Rosenkranz, Federal Rules of Statutory Interpretation, 115 Harv. L. Rev. 2085, 2094 (2002); Jeffrey A. Love, Comment, Fair Notice about Fair Notice, 121 Yale L.J. 2395, 2401 (2012).

The rule of lenity also has its detractors. It has been criticized as negating legislation, being uncertain and arbitrary in application and scope, unnecessary, not justified, and undercutting the rule of law. In 1776, the rule of lenity was described as “the subject of more constant controversy than perhaps of any in the whole circle of the Law.”4Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts 296 n.3 (2012) (quoting Jeremy Bentham, A Comment on the Commentaries: A Criticism of William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England 141 (Charles Warren Everett, ed., 1928)).

Despite its critics, the rule of lenity has been a part of the US legal system for more than two centuries. The rule of lenity is deeply embedded in federal courts and is broadly adopted in state courts. Notwithstanding this deep and broad acceptance, however, several state legislatures have enacted statutes negating the rule of lenity.

This state statutory anti-lenity effort started in the early 1800s and came in phases. By the mid-1800s, as a product of codification efforts in Texas and then New York, state anti-lenity statutes became more focused and uniform. In 1864, Oregon enacted what would become the prototype anti-lenity statute:

The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to [the criminal code], but all [the criminal code’s] provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.5Or. Crim. Code tit. 2, ch. 14, § 787 (1864).

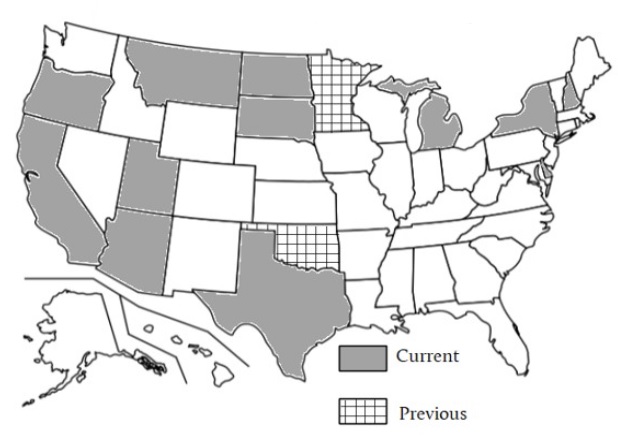

Other states followed. By the early 1900s, ten states or territories, mostly in the western part of the United States, had enacted nearly identical anti-lenity statutes. These statutes: (1) state strict construction does not apply to the state’s criminal code; and (2) provide direction about how the state’s criminal code should be construed. The legislative pace slowed in the twentieth century, with four states enacting anti-lenity statutes, two states repealing anti-lenity statutes, and one state considering—but not enacting—such a statute.

Currently, a dozen states have virtually identical anti-lenity statutes that prototypically state: “The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this code. The provisions of this code shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to promote justice and effect the objectives of the code.”6Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 1.05(a) (West, Westlaw through 2019 Sess.). States that currently have anti-lenity statutes and their text are listed in Appendix 2. This Article refers to these statutes as “anti-lenity statutes,” consistent with prior usage. See, e.g., People v. Morrison, 191 Cal. App. 4th 1551, 1556–57 (Cal. Ct. App. 2011); Daniel Ortner, The Merciful Corpus: The Rule of Lenity, Ambiguity and Corpus Linguistics, 25 B.U. Pub. Int. L.J. 101, 108 n.58 (2016); Love, supra note 3, at 2398–99. This anti-lenity effort is uniquely a state law undertaking; there has never been a generally applicable federal anti-lenity statute. This Article examines these state anti-lenity statutes—their origin, history, application, and implications—in the context of the rule of lenity, states’ rights, federalism, due process, separation of powers, and other concepts.

This Article begins with an overview of the common-law rule of lenity by discussing its origins in England and then early and widespread adoption in the United States, both in federal and state courts.7See infra Section I. This Article next highlights the justifications for, and criticisms of, the rule of lenity and how model laws have addressed the rule of lenity.8See infra Section II.

This Article then turns to the adoption of state anti-lenity statutes, starting with precursor legislation coming in three phases in the first part of the 1800s.9See infra Section III.A. Next, this Article discusses codification efforts in Texas and New York in the mid-1800s, where the state anti-lenity statute began in earnest.10See infra Section III.B(1)–(2). These efforts resulted in ten anti-lenity enactments through the early 1900s.11See infra Section III.B(3). This Article then addresses enactments, repeals, and an attempted enactment in the 1900s, with particular emphasis on efforts in the 1960s and early 1970s as a part of broader state criminal code reform effort.12See infra Section III.B(4).

This Article then discusses how state courts have applied these provisions in the dozen states that currently have such anti-lenity statutes. This discussion highlights opinions: (1) where application of the anti-lenity statute is outcome determinative; (2) where application of the statute is used to distinguish statutory construction efforts in jurisdictions without such a statute; (3) attempting to reconcile the rule of lenity with the anti-lenity statute; and (4) raising due process and separation of powers concerns about anti-lenity statutes.13See infra Section IV.A(1)–(5). This Article then provides an overview of the far larger number of opinions that simply mention anti-lenity statutes without any significant analysis, including those that ignore (either literally or substantively) the statutory directive prohibiting strict construction of criminal statutes.14See infra Section IV.A(6). This Article follows with a discussion of the extremely small number of federal court opinions citing state anti-lenity statutes.15See infra Section IV.B.

The analysis then shows that state anti-lenity statutes should be applied as written, as properly enacted statutes that can, at times, be outcome determinative. Concluding that the common law rule of lenity cannot be squared with state anti-lenity statutes prohibiting criminal statutes from being strictly construed, the analysis rejects as unpersuasive the small number of opinions attempting to reconcile the two concepts. Discussing the due process and separation of powers concerns sometimes noted in opinions discussing state anti-lenity statutes, this Article rejects the thought that state anti-lenity statutes violate those constitutional provisions. Moreover, until a state anti-lenity statute is declared unconstitutional—and none have been to date—state anti-lenity statutes should be applied as written. Even if an anti-lenity statute could somehow be reconciled with the rule of lenity, or is deemed to violate a constitutional provision, a court reaching that conclusion should do so expressly with supporting analysis and rationale, and not simply ignore the applicable state anti-lenity statute.16See infra Section V.

A critical, core function of the state judicial system in the United States is the application of state criminal law. In recent years, nearly twenty million new criminal cases have been filed each year in state courts.17See Total Incoming Criminal Caseloads Reported by State Courts, All States, 2007-2016, Court Statistics Project, https://perma.cc/3DAZ-86FL. Given this volume, it is curious that state anti-lenity statutes—currently in place in a dozen states and the law in some for more than 150 years—broadly addressing the construction of criminal statutes have virtually been ignored. How and where this long, strange trip for these state anti-lenity statutes ends is unknown. What is clear, however, is that state anti-lenity statutes can and should have force, should be applied by the courts where applicable, and should not be ignored.

I. Evolution of the Rule of Lenity

A. The Rule of Lenity in England

The strange trip leading to state anti-lenity statutes starts with the evolution of the rule of lenity in England centuries ago. In fourteenth century England, “the death penalty was imposed on a multitude of crimes without regard to their severity, mitigating or aggravating circumstances, or the defendant’s character.”18Newland, supra note 1, at 199. A possible defense, however, was “the doctrine of the benefit of clergy,” which was “based on a literacy test.”19Id. at 199–200 & n.12 (citing Livingston Hall, Strict or Liberal Construction of Penal Statutes, 48 Harv. L. Rev. 748, 749 (1935)). This “‘benefit of the clergy,’ granted immunity to prosecution to those who could read portions of the Bible.”20Lawrence M. Solan, Law, Language, and Lenity, 40 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 57, 87 (1998).

As the literacy rate in England increased, criminal defendants more frequently were able to invoke the benefit of clergy defense.21See Hall, supra note 19, at 749; see also Dan M. Kahan, Lenity and Federal Common Law Crimes, 1994 Sup. Ct. Rev. 345, 358; Zachary Price, The Rule of Lenity as a Rule of Structure, 72 Fordham L. Rev. 885, 897 (2004). By the end of the fifteenth century, the increase in the number of defendants successfully invoking the benefit of clergy defense prompted legislation that eliminated the defense for certain offenses.22See Hall, supra note 19, at 749. Over time, legislation excluded more and more offenses from the benefit of clergy defense, “resulting in a ‘march to the gallows.’”23Newland, supra note 1, at 200. By the seventeenth century, crimes subject to the death penalty ranged from the predictable (murdering the King), to the trivial (pick-pocketing), to those forgotten to time (“being in the company of gypsies”).24Id.

In response, courts in England began to strictly construe criminal statutes in favor of criminal defendants.25See id. Strict construction

did not become a general rule of conscious application until the growing humanitarianism of 17th century England came into serious conflict with the older laws of the preceding century. . . . [As a result of eliminating the benefit of clergy for various forms of theft] a conflict ensued between the legislature on the one hand and courts, juries, and even prosecutors on the other. The former was committed by inertia, or pressure from property owners, to a policy of deterrence through severity, while the latter tempered this severity with strict construction carried to its most absurd limits, verdicts contrary to the evidence, and waiver of the non-clergyable charge in return for a plea of guilty to a lesser offense. It was from cases and text writers in the England of this period that the doctrine of strict construction was brought to [the United States].26Hall, supra note 19, at 750–51.

B. The Rule of Lenity in United States Federal Courts

In the United States, the rule of lenity took hold almost immediately. In 1820, the US Supreme Court first applied the rule of lenity in United States v. Wiltberger.2718 U.S. 76 (1820). Wiltberger involved the first Crimes Act of the United States, enacted in 1790, which made it a crime to “commit manslaughter on the high seas.”28Id. at 93; see alsoUnited States v. Rodgers, 150 U.S. 249, 267 (1893) (discussing Wiltberger); Kahan, supra note 21, at 357 (“Wiltberger involved a defective statute. Section 8 of the Crimes Act of 1790 (the very first piece of criminal legislation enacted by Congress).”). The issue was whether the defendant, who was found guilty of killing a seaman on board a ship in the Tigris river in China “about 100 yards from the shore, in four and a half fathoms [about 27 feet of] water,” had done so on “the high seas.”29Wiltberger, 18 U.S. at 77, 94.

Chief Justice John Marshall, writing for a unanimous court, adopted the “well-known rule” of lenity, declaring “[t]he rule that penal laws are to be construed strictly, is perhaps not much less old than construction itself.”30Id. at 94–95. Wiltberger explained that the rule of lenity

is founded on the tenderness of the law for the rights of individuals; and on the plain principle that the power of punishment is vested in the legislative, not in the judicial department. It is the legislature, not the Court, which is to define a crime, and ordain its punishment.31Id. at 95.

Wiltberger then limited the application of the rule: “[w]here there is no ambiguity in the words, there is no room for construction,” adding that although “penal laws are to be construed strictly, they are not to be construed so strictly as to defeat the obvious intention of the legislature.”32Id. at 95–96. On the facts presented, Wiltberger found the offense was not committed “on the high seas,” and vacated the conviction.33See id. at 103, 105.

The US Supreme Court has applied this rule of lenity many times in the two centuries that followed.34For a thoughtful discussion of the US Supreme Court’s varied use of the rule of lenity over time, see generally Solan, supra note 20, at 58–61. The Court’s use of the term “lenity,” however, did not start in earnest until the mid-1950s.35See Bell v. United States, 349 U.S. 81, 83 (1955) (noting, in a case turning on the appropriate “unit of prosecution” for criminal acts that could be considered one or more than one offense, “[w]hen Congress leaves to the Judiciary the task of imputing to Congress an undeclared will, the ambiguity should be resolved in favor of lenity”). In fact, of the one hundred and fifty-three decisions where the Court has used the term “lenity,” one hundred and nineteen were decided since 1980.36A June 20, 2020 “U.S. Supreme Court” Westlaw database search for “lenity” limited to the full text of opinions revealed one hundred and fifty-three cases, with Bell containing the first use of the term “lenity” as relevant here.

Along with this early adoption by the US Supreme Court, other federal courts widely adopted the rule of lenity.37Other federal courts had recognized the rule of lenity by 1810, a decade before Wiltberger. See The Enterprise, 8 F. Cas. 732, 734 (Cir. Ct. D. N.Y. 1810) (“The act, and particularly that part of it under which a forfeiture is claimed, is highly penal, and must therefore be construed as such laws always have been and ever should be. But while it is said that penal statutes are to receive a strict construction, nothing more is meant than that they shall not, by what may be thought their spirit or equity, be extended to offences other than those which are specially and clearly described and provided for.”); see also United States v. Hare, 26 F. Cas. 148, 156 (Cir. Ct. D. Md. 1818) (“It is admitted that penal statutes should be construed strictly; that is, they shall be construed according to the strict letter in favor of the person accused, if there be any ambiguity in the language of the statute.”); United States v. Clark, 25 F. Cas. 441, 443 (Cir. Ct. D. Mass. 1813) (“I have already stated the general rule, as to penal statutes, that their construction is strict; a rule that, in cases of doubtful meaning, always inclines the court to that, which is most favorable to the defendant, unless it be repelled by the context.”). All US Circuit Courts of Appeal have done so,38See Appendix 1 at 1–2 (listing recent cases from all federal circuit courts of appeal doing so). and US District Court decisions citing the rule of lenity number in the thousands.39A June 20, 2020 “Federal District Court” Westlaw database search for “lenity” limited to the full text revealed 3,153 cases, 983 of which were reported opinions. The rule of lenity is stated in a variety of ways, including, for example, differences in comparatively recent US Supreme Court decisions about what type of ambiguity is required. See, e.g., Voisine v. United States, 136 S. Ct. 2272, 2282 n.6 (2016) (citing Abramski v. United States, 134 S. Ct. 2259, 2272 n.10 (2014) for the proposition “genuine ambiguity” is required (emphasis added)); Muscarello v. United States, 524 U.S. 125, 138 (1998) (“somestatutory ambiguity” is not sufficient (emphasis added)); Chapman v. United States, 500 U.S. 453, 463 (1991) (“grievousambiguity or uncertainty in the language and structure of the Act” is required (emphasis added)); Crandon v. United States, 494 U.S. 152, 158 (1990) (noting that “any ambiguity in the ambit of the statute’s coverage” is sufficient (emphasis added)). The precise phraseology used for the rule of lenity (including differences in how the rule is characterized) is not the focus of this Article. Rather, the focus here is the enactment and application of state anti-lenity statutes to negate the rule of lenity.

C. The Rule of Lenity in State Courts

State courts recognized the rule of lenity decades before the US Supreme Court did so in Wiltberger. In 1790, New Jersey’s Supreme Court of Judicature did so in a slander case.40See Smith v. Minor, 1 N.J.L. 16, 16 (N.J. Sup. Ct. of Judicature 1790). In affirming a judgment for the plaintiff, the court addressed whether fornication was indictable as a crime, noting “by the rules of construction [criminal law] cannot . . . be extended to cases which do not come within its express words.”41Id. at 22. The quoted language erroneously contains an extra “not”—stating “by the rules of construction cannot not be extended to cases”—and the quoted language in the text corrects for that error. Ultimately, the court concluded that fornication “when unproductive” was not an indictable offense, concluding:It would lead to inquiries too indecent to be brought before the public; it would subject behavior perhaps at worst merely imprudent, to critical investigation; and leave the actions and behavior of innocent persons exposed to idle conjecture, to unwarrantable construction, and impertinent curiosity; and the indecency of the inquiries would produce more harm than prosecutions would do good.”Id. By the time Wiltberger was decided in 1820, courts in at least seven of the twenty-two states had recognized the rule of lenity.42See Fairbanks v. Town of Antrim, 2 N.H. 105, 107 (N.H. Super. Ct. of Judicature 1819) (“[I]t is urged, and the argument is a truism in the books, that the construction of penal statutes should be strict.”); State v. Jernigan, 3 Mur. 12, 15 (N.C. 1819) (considering, but rejecting on facts presented, argument “that the act being highly penal, ought to receive a strict construction, and on the side of lenity”); Commonwealth v. Duane, 1 Binn. 601, 609 (Pa. 1809) (“In nothing is the common law, which we have inherited from our ancestors, more conspicuous, than in its mild and merciful intendments towards those who are the objects of punishment.”); Jones v. Estis, 2 Johns. 379, 380 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. of Judicature 1807) (“[A] penalty cannot be raised by implication, but must be expressly created and imposed.”); Elliott v. Richards, 1 Del. Cas. 87, 88 (Del. Ct. C.P. 1796) (“The rule that a penal statute ought to be construed strictly, and the letter must be attended to, and that it cannot extend to crimes not mentioned in it, is a good rule and cited in many books.”); Oldum v. Allerton & Pope, 2 Va. Col. Dec. B331, 1739 WL 12, at *7 (Gen. Ct. Va. 1739) (noting “the Justice here was resolved to stop the Fountain of the Kings Lenity & effectually to ruin the [plaintiff]”); Smith v. Minor, 1 N.J.L. 16, 22 (N.J. Sup. Ct. of Judicature 1790). Over time, courts in all fifty states and the District of Columbia acknowledged the rule of lenity.43See Appendix 1 at 3–10 (listing cases).

II. Justifications for, and Criticisms of, the Rule of Lenity

As “one of the oldest tools of statutory construction,”44Elliot Greenfield, A Lenity Exception to Chevron Deference, 58 Baylor L. Rev. 1, 11 (2006) (citing Solan, supra note 20). many justifications for, and criticisms of, the rule of lenity have been offered. Stated broadly, summaries of the various rationale offered for those justifications and criticisms include the following.

A. Justifications for the Rule of Lenity

Fair Notice and Fairness. The rule of lenity is said to further the thought that it is essential to provide fair notice of what criminal laws prohibit.45See, e.g., John L. Diamond, Reviving Lenity and Honest Belief at the Boundaries of Criminal Law, 44 U. Mich. J.L. Reform, 1, 32 (2010) (citing William N. Eskridge, Jr. et al., Legislation: Statutes and the Creation of Public Policy 851–54 (3d ed. 2001)); Greenfield, supra note 44, at 12; Solan, supra note 20, at 134–41. In this respect, the rule of lenity reflects and protects due process concepts of fair notice of what is considered criminal, with commentators suggesting “that the due process principles of notice require courts to construe ambiguities in favor of accused criminals.”46See Alan R. Romero, Note, Interpretive Directions in Statutes, 31 Harv. J. on Legis. 211, 230 (1994); see also Richard H. Fallon, The Statutory Interpretation Muddle, 114 NW. U. L. Rev. 269, 321 (2019) (“Considerations of justice and fairness undergird the rule of lenity.”); Greenfield, supra note 44, at 14 (citing William N. Eskridge, Jr. & Philip P. Frickey, Quasi-Constitutional Law: Clear Statement Rules as Constitutional Lawmaking, 45 Vand. L. Rev. 593, 600 (1992)); Richard M. Re, Clarity Doctrines, 86 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1497, 1549 n.211 (2019) (“Lenity’s concern for notice and fairness—and, therefore, for predictability—sits alongside other legally recognized goals.”).

Separation of Powers: Legislative-Judicial. “[T]he power of punishment is vested in the legislative, not in the judicial department. It is the legislature, not the Court, which is to define a crime, and ordain its punishment.”47United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. 76, 43 (1820); see also United States v. Bass, 404 U.S. 336, 348 (1971) (“[B]ecause of the seriousness of criminal penalties, and because criminal punishment usually represents the moral condemnation of the community, legislatures and not courts should define criminal activity.”); accord Diamond, supra note 45, at 32. Furthermore, [i]t would certainly be dangerous if the legislature could set a net large enough to catch all possible offenders and leave it to the courts to step inside and say who could be rightfully detained, and who should be set at large. This would, to some extent, substitute the judicial for the legislative department of government. Lisa K. Sachs, Strict Construction of the Rule of Lenity in the Interpretation of Environmental Crimes, 5 N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J.600, 603 (1996) (quoting United States v. Reese, 92 U.S. 214, 221 (1875)). Lenity is said to have a “role in advancing the democratic accountability of criminal justice,” given that broad (liberal) construction of criminal statutes runs “a risk of interpretations that conform to the letter of the statute but not to the understanding of the crime that an informed voter would have had at the time it was passed.”48Price, supra note 21, at 887. The rule of lenity also is said to prevent legislators “from passing off the details of criminal lawmaking to courts.”49Id. at 909.

Separation of Powers: Legislative-Executive. The rule of lenity is said to ensure “that the legislature, and not the executive acting through its agent-prosecutor, proscribes and determines the threshold of criminal behavior.”50Diamond, supra note 45, at 32. Lenity may limit “novel theories [of prosecution] without a democratic mandate;” could “permit juries to impose beneficial discipline on prosecutors,”51Price, supra note 21, at 919–20. and prevent “arbitrary law enforcement.”52Kahan, supra note 21, at 405 (also noting that this rationale “is as uncompelling (descriptively and normatively) as the fair warning rationale”).

Separation of Powers: Legislative-Executive-Judicial. Lenity is said to require legislators to “agree on legislative details; they may not delegate the fine-tuning to the executive or judiciary.”53Price, supra note 21, at 915. More generally, the US Supreme Court has found a purpose for lenity is “to maintain the proper balance between Congress, prosecutors, and courts.”54United States v. Kozminski, 487 U.S. 931, 952 (1988) (also stating the purpose underlying lenity is “to promote fair notice to those subject to the criminal laws, [and] to minimize the risk of selective or arbitrary enforcement”).

Political Realism And Accountability. Without the rule of lenity it is said that judicial interpretation of criminal statutes would be broad and no constituency would be able to secure passage of corrective (narrowing) legislation, while with the rule of lenity, corrective legislation is more likely.55See Einer Elhauge, Preference-Eliciting Statutory Default Rules, 102 Colum. L. Rev. 2162, 2194 (2002). In addition, the rule of lenity may be read as furthering the liberty interest of criminal defendants to the extent that interest “requires that all doubts be resolved in their favor,” or to “lean in favor of criminal defendants because they are ‘under-represented’ in the legislative process.” Id. at 2197. The rule of lenity also is said to lead to more transparency from legislators in passing laws and in executive action in enforcing them.56See Price, supra note 21, at 888 (“[T]he best justification for the rule of lenity may be its service to governmental transparency and accountability. The rule guarantees explicit notification of the meaning of criminal legislation, and it makes prosecutors’ charging policies more transparent to voters and juries. Given that criminal law otherwise tends to surpass popular expectations about what conduct is seriously wrongful, these disclosure effects are vital to the moral and political legitimacy of criminal law.”).

Legislative Clarity. The rule of lenity encourages more specificity in legislation that, in turn, may encounter more political resistance,57See id. at 916–17. which “forces the legislature to define just how anti-criminal they wish to be, and how far to go with the interest in punishing crime when it runs up against other societal interests.”58Elhauge,supra note 55, at 2194.

Judicial Restraint. The rule of lenity is said to reflect “judicial restraint, ensuring that the court did not extend the scope of a statute beyond clear legislative intent.”59Sachs, supra note 47, at 604.

Presumption in Favor of the Defendant. The rule of lenity “requires courts to construe ambiguous statutes in favor of criminal defendants and so effectively creates a presumption in favor of the defendant, shifting the burden to the government to prove the statute should not be so construed.”60Abbe R. Gluck, Intersystemic Statutory Interpretation: Methodology as “Law” and the Erie Doctrine, 120 Yale L.J. 1898, 1978–79 (2011).

Federalism And States’ Rights. The rule of lenity can promote federalism, particularly when focusing on the interplay between federal and state criminal law.61See Kahan, supra note 21, at 421. In addition, a federal court holding that a state criminal statute is unconstitutional is a blow to federalism and states’ rights, with resulting doctrinal confusion, uncertainty, and worse.62See Stuart Buck & Mark Rienzi, Federal Courts, Overbreadth, and Vagueness: Guiding Principles for Constitutional Challenges to Uninterpreted State Statutes, 2002 Utah L. Rev. 381, 381. The rule of lenity helps avoid such an outcome and, along the way, furthers federalism and states’ rights.63Although outside of the scope of this Article, the rule of lenity applicable to federal criminal statutes similarly may be seen as furthering federalism interests. See Royce de R. Barondes, Contumacious Responses to Firearms Legislation (LEOSA) Balancing Federalism Concerns, 56 Hous. L. Rev. 1, 21 n.100 (2018) (citing Justice Scalia’s concurrence in Fowler v. United States, 563 U.S. 668, 684–85 (2001), as “identifying a federalism interest supporting lenity in rejecting an interpretation that would federally criminalize local criminal conduct.”); accord Julian R. Murphy, Lenity and the Constitution: Could Congress Abrogate the Rule of Lenity?, 56 Harv. J. on Legis. 423, 437–38, n. 87 (2019) (citing authority discussing the rule of lenity applicable to federal criminal statutes).

The Rule of Law. By encouraging clear statutes and reducing the possibility of prosecutorial abuse, the rule of lenity is said to promote the rule of law.64See Note, The New Rule of Lenity, 119 Harv. L. Rev. 2420, 2426 (2006); see also Murphy, supra note 63, at 435–37, n. 76 (citing and discussing, but apparently dismissing, various suggestions that the rule of law provides a constitutional foundation for the rule of lenity).

Other Justifications. Other justifications for the rule of lenity include serving a function akin to constitutional avoidance;65See Greenfield, supra note 44, at 14. “ensur[ing] that the legislative will is vindicated”; “protect[ing] against overcriminalization”; and “ensur[ing] that the politically powerless are given a fair shake.”66Love, supra note 3, at 2401; see also Diamond, supra note 45, at 32 (pointing to “humanitarian considerations, most particularly in the context of capital punishment”) (citing Eskridge, supra note 45, at 851–54).

B. Criticisms of the Rule of Lenity

The Fallacy Of Notice. The thought that notice concerns justify lenity is said to be “flawed because criminals do not read statutes, and because even if they did it would not be clear that the legal system should reward their efforts to skirt the law’s borders.”67Price, supra note 21, at 886.

Negating Legislation. The rule of lenity requires courts to select a strict interpretation of a statute, even though that may negate the purpose of the legislation68See id. and “conduct that can reasonably be considered criminal is hardly politically popular.”69Elhauge, supra note 55, at 2193; see also id. (noting that, “if one had to make an educated estimate (and given the premise of ambiguity, one must), one might perhaps even conclude that in ambiguous cases the legislature would likely prefer a ‘rule of severity’—the greater punishment for the criminal defendant”).

Uncertainty In Application. The rule of lenity is criticized as leading to uncertain outcomes, particularly because ambiguity may be in the eye of the beholder.70See Greenfield, supra note 44, at 14. Moreover, the US Supreme Court has stated there must be a “grievous ambiguity or uncertainty”71Muscarello v. United States, 524 U.S. 125, 138–39 (1998). before lenity applies, adding a qualitative component (what is “grievous”) to an already often subjective inquiry (what is “ambiguous”).72Greenfield, supra note 44, at 14–15 (noting there must be an actual ambiguity for lenity to apply and, even then, “[l]enity may only be applied if the statutory ambiguity is substantial”).

The analytical point at which a court should invoke the rule of lenity also can add uncertainty.73See Sachs, supranote 47, at 618. Although the issue of whether a statute is ambiguous could focus on the statutory language written as applied to the facts presented, at times, the rule of lenity has been said to apply only “at the end of the process of construing”74Callanan v. United States, 364 U.S. 587, 596 (1961). statutory language—when “a reasonable doubt persists about a statute’s intended scope even after resort to ‘the language and structure, legislative history, and motivating policies’ of the statute.”75Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 108 (1990); see also United States v. Wells, 519 U.S. 482, 499 (1997) (“The rule of lenity applies only if, ‘after seizing everything from which aid can be derived,’ we can make ‘no more than a guess as to what Congress intended.’”). This, in turn, implicates debate about the proper use of legislative history in undertaking the inquiry.76See Greenfield, supra note 44, at 15–16.

Arbitrary Application. Application of the rule of lenity has been characterized as a “complex and slippery doctrine”;77Price, supra note 21, at 888. “‘notoriously sporadic and unpredictable’ or ‘bizarre’”;78Note, supra note 64, at 2423. “dubious”;79Elhauge, supra note 55, at 2196. “open to manipulation”;80Price, supra note 21, at 888–89. inconsistent; and random.81See Note, supra note 64, at 2420 (“Observers argue that courts apply the rule inconsistently, or even randomly. Many go further and claim that courts have stopped applying it altogether. These critics explain the routine invocations of the rule of lenity as mere lip service: courts may nominally acknowledge the rule, but they find statutes to be unambiguous and therefore decline to apply it unless they would have found for the defendant on other grounds anyway.”. Others assert that application of the rule of lenity turns on a judicial officer’s philosophy of statutory construction or interpretation, or general judicial philosophy.82See Kahan, supra note 21, at 393 (discussing Moskal and stating “[t]he Justices who comprise the ‘pro-lenity’ contingent include those who are typically counted as the Court’s most ‘conservative’ members, while the ‘anti-lenity’ group includes those typically described as its most ‘liberal’”). Critics claim the rule of lenity has been applied when it should not be and “overlooked when it ought to apply.”83Scalia & Garner, supra note 4, at 298–300.

Uncertain Scope. Although classically applicable only to criminal statutes, the US Supreme Court has applied the rule of lenity to criminal statutes implicated in civil cases,84See Greenfield, supra note 44, at 16. and in cases where the statute at issue might have any criminal application.85See id. at 17. In these additional ways, the precise scope of the rule is claimed to be ill defined.

Result Oriented. The rule of lenity has been criticized as a result-oriented tool “and criticized by judicial realists as an interpretative shortcut.”86Newland, supra note 1, at 197 n.4.

Unnecessary. When prosecutorial discretion is exercised properly, it is said there is no need for the rule of lenity.87See Diamond, supra note 45, at 32–33.

Not Justified. Some critics of the rule of lenity assert it should be abolished because “it cannot be justified by any of its traditional rationales and therefore [these critics] conclude that the courts would do well to make their abandonment of the rule official.”88Note, supra note 64, at 2420.

Undercutting The Rule Of Law. Given the lack of consistent application—which undercuts the notice justification for the rule of lenity—one commentator concludes that “[a] rule of lenity whose application is uncertain may be just as problematic from a fair-notice perspective as having no rule of lenity at all.”89Love, supra note 3, at 2400.

Other Criticisms. The rule has variously been called a “makeweight,” “capricious,” and “random [in] invocation.”90Note, supra note 64, at 2423 n.26.

C. Model Law Responses to the Rule of Lenity

These divergent views of the rule of lenity are reflected in state statutory law, including how the rule is addressed in model acts. The Model Penal Code, promulgated in 1962 by the American Law Institute after more than thirty years of work,91See Herbert Wechsler, The Challenge of a Model Penal Code, 65 Harv. L. Rev. 1097, 1097 & n.1 (1952) (noting “a proposal to prepare a model penal code” effort “was first advanced in 1931”). broadly influenced state criminal law.92See Sanford H. Kadish, Fifty Years of Criminal Law: An Opinionated Review, 87 Cal. L. Rev. 943, 948 (1999) (“The success of the [Model Penal] Code in stimulating American jurisdictions to codify or recodify their criminal law was unprecedented.”). The Model Penal Code rejected the rule of lenity,93See Diamond, supra note 45, at 35–36 (discussing Model Penal Code rejecting lenity); see also Darryl K. Brown, Plain Meaning, Practical Reasons, and Culpability: Toward a Theory of Jury Interpretation of Criminal Statutes, 96 Mich. L. Rev. 1199, 1246 n.218 (1998) (“The Model Penal Code replaces the lenity rule with one requiring that statutory terms be given their ‘fair import.’”). using instead a statutory directive that “[t]he provisions of the Code shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms but when the language is susceptible of differing constructions it shall be interpreted to further the general purposes stated in this Section and the special purposes of the particular provision involved.”94Model Penal Code § 1.02(3) (Am. L. Inst. 1962). The Explanatory Note made plain that this provision displaced the rule of lenity, stating it

replaces the rule that penal statutes should be “strictly construed” with the command that criminal statutes should be construed according to their fair import, and that ambiguities should be resolved by an interpretation that will further the general principles stated in this Section, including specifically the fair warning provisions, and the special purposes of the statute involved.95Id. § 1.02 Explanatory Note on Subsection (3).

The related Comment expressed concern with the rule of lenity more broadly:

The ancient rule that penal law must be strictly construed, found in many American penal codes, is not preserved as such because it unduly emphasized only one aspect of the problem that the courts must face. . . . Construction of ambiguous statutes in terms that strike an accommodation of the general principles here set forth, including the fair warning concept, is a far more desirable charge.96Id. § 1.02 Cmt. 4.

The Model Penal Code was not alone in rejecting the rule of lenity. The Model State Statute and Rule Construction Act, promulgated by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws in 1995, was even more pointed in doing so.97Originally approved as a Uniform Act, in 2003, the Uniform Law Commission changed the designation to a Model Act. See Uniform Statute and Rule Construction Act n.* (Nat’l Conf. Comm’rs Unif. State Laws 1995). Although not nearly as widely adopted as the Model Penal Code,98See, e.g., N.M. Stat. Ann. § 12-2A-18 (West 2020). the Model State Statute and Rule Construction Act did not include a provision on how criminal statutes should be construed.99See Model Statute and Rule Construction Act § 18 (Nat’l Conf. Comm’rs Unif. State Laws 1995). The related Comment cites authority “demonstrat[ing] that courts do not consistently apply the presumption,” adds that the US Supreme Court “has not applied the presumption consistently,” and states: “The presumption that penal statutes shall be strictly construed is not included in this Act. Like the presumption about statutes in derogation of the common law, this presumption has been expressly rejected in a number of States.”100Id. § 18 Cmt. on The Construction Process (citing, inter alia, Hall, supra note 19, at 748). The Comment continued that “a State that recognizes the presumption that a penal statute shall be strictly construed, and desires to retain that presumption, will need to add an appropriate subsection to this section.” Id.

The concerns expressed about the rule of lenity in these Model acts reflect age-old debates about the rule. Consistent with these debates, state and territorial legislatures enacted statutory responses to the rule of lenity starting at about the same time US courts began recognizing the rule of lenity. Although starting in different places and appearing in different forms, these efforts led to the adoption of today’s quite consistent state anti-lenity statutes.

III. Adoption of State Anti-Lenity Statutes

A. Precursor State Legislation in the Early 1800s

Frustration in state legislatures with the rule’s application—at the same time it was being recognized by US courts—“led to direct action by the legislatures of many states to overthrow, in whole or in part,” the rule of lenity.101Hall,supra note 19, at 752.

Starting with Arkansas in 1838, statutes modifying the common-law rule [of lenity] as to all penal laws became more and more common as commissioners appointed to revise the penal codes of the older states, or draft new ones for territories on their admission to statehood, came to feel that their labors might be more or less undone by judges applying the old rules. . . . The movement occurred chiefly in the West; [as of 1935,] sixteen of the twenty-two states west of the Mississippi have such statutes, while in the rest of the country they are found only in New York, Illinois, and Kentucky.102Id. at 753–54 (footnotes omitted).

But this “movement” was not monolithic; instead, it was a long, strange trip, coming at different times and in different forms that defy concise summary. Stated simply, however, the effort came in three phases, the first of which began in the early 1800s. Listed chronologically, these three phases are:

(1) Statutes directing the broad (or liberal) construction of the criminal code. These statutes direct broad (or liberal) construction of the criminal code, either tacitly or by expressly providing that the rule of lenity (strict construction) does not apply. These statutes moved statutory construction dramatically, by rejecting lenity and replacing it with broad construction, but with no further guidance.

(2) Statutes rejecting the concept that statutes in derogation of the common law should be strictly construed.Although perhaps appearing similar to anti-lenity statutes, these statutes are really quite different. The US Supreme Court recognized the concept of strictly construing statutes in derogation of the common law decades before Wiltbergerrecognized the rule of lenity,103See Brown v. Barry, 3 U.S. 365, 367 (1797) (“And the act of 1789, being in derogation of the common law, is to be taken strictly.”). and has made clear that the two concepts are different.104See Johnson v. Southern Pac. Co., 196 U.S. 1, 17–18 (1904) (applying separate analysis in finding circuit court erred in concluding a statute should have been strictly construed both “because the common-law rule . . . was changed by the act, and because the act was penal” (emphasis added)). Among other things, strictly construing statutes in derogation of the common law: (a) “only amounts to the recognition of a presumption against an intention to change existing law”;105Id. at 17. (b) applies to all statutes (not just criminal statutes); and (c) limits the scope of a statute regardless of whether doing so favors a criminal defendant or is against the government. Although quite different than anti-lenity statutes, these state statutes rejecting the concept that statutes in derogation of the common law should be strictly construed are referenced here for context and completeness, particularly given they have been discussed elsewhere in addressing state anti-lenity statutes.106See Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.25 & 754.

(3) Statutes rejecting lenity and directing the criminal code is to be construed according to the fair import of its terms and to promote justice (and, at times, referencing specific purposes). These statutes—true state anti-lenity statutes—are more express alternatives to the first phase statutes in that they negate lenity but add that construction should be guided by specific directives (not generic “broadly” or “liberally” directives). The statutes in this third phase are the state anti-lenity statutes analyzed in this Article.

The phase one effort—statutory provisions directing that statutes should be liberally construed—started by first targeting specific statutory provisions. In 1802, for example, Virginia enacted a statute providing “for ‘remedial’ (i.e., liberal) construction of statutes against gaming,” with Tennessee enacting similar legislation in 1824.107Id. at 752 n.22 (citing 1802 Va. Acts, c. 35, § 9 and 1824 Tenn. Acts, c. 5, § 5). The reason for these enactments appear lost to time. The general concept of lenity in Virginia’s courts, however, appears to trace back to colonial days. See Oldum v. Alterton & Pope, 2 Va. Col. Dec. B331 (Gen. Ct. Va. 1739) (discussing, in language that does not readily translate to today’s opinions, whether a Justice of the Peace exceeded his authority in securing a witness, and stating the following: “This is exceeding [sic] Power with a witness It is not at [sic] unlikely the Legislature designed in not appropriating the Penalty to leave Room for an Application to the Crown where a Justice was too severe or partial[.] It might be thought a proper Security ag’t arbitrary & violent Proceedings[.] But the Justice here was resolved to stop the Fountain of the Kings Lenity & effectually to ruin the” plaintiff). No similar case from Tennessee predating the 1824 enactment was located. Some states expanded this legislative effort by requiring liberal construction of statutory enactments more broadly.

In 1838, Arkansas enacted a statute providing that “[a]ll general provisions, terms, phrases, and expressions, used in any statute, shall be liberally construed, in order that the true intent and meaning of the General Assembly may be fully carried out.”108Ark. Rev. Stat., ch. 129, § 22 (1838); see also Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.24. This directive applied to civil and criminal statutes alike unless context or an express provision provided otherwise.109See Ark. Rev. Stat., ch. 129, § 23 (1838); see also Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.24. Other states followed with similar legislation: Illinois (1845);110See Ill. Rev. Stat., ch. 90, § 36 (1845). Colorado (1861);111See Colo. Rev. Stat., ch. 79, § 3 (1861) (“All general provisions, terms, phrases and expressions, used in any statute, shall be liberally construed, in order that the true intent and meaning of the general assembly may be fully carried out.”). and Washington state (1891).112See 1891 Wash. Laws, p. 40, § 1, cited in Code of Procedure and Penal Code of the State of Washington tit. VI, ch. 58, § 702 (1893) (“The provisions of this code shall be liberally construed and shall not be limited by any rule of strict construction.”).

The phase two effort (rejecting the notion that statutes in derogation of the common law should be strictly construed) emerged in 1851, when Iowa enacted a statute directing that “[t]he rule that laws in derogation of the common law are to be strictly construed has no application to this statute, but shall receive a liberal construction in order to carry out its general purpose and objects.”113See Iowa Code tit. 22, ch. 134, § 2503 (1851). Nearly identical statutes followed in Kentucky (1852);114See Ky. Rev. Stat., ch. 21, § 16 (1852) (“The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, is not to apply to this revision; on the contrary, its provisions are to be liberally construed, with a view to promote its objects.”). The proceeding section directed that “[t]here shall be no distinction in the construction of statutes, between criminal or civil and penal enactments. All statutes shall be construed with a view to carry out the intention of the legislature.” Id. § 15. Dakota Territory (1862);115See Dakota Terr. Code of Civ. Pro.,ch. 8, § 2 (1862) (“The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. Its provisions, and all proceedings under it, shall be liberally construed, with a view to promote its object, and assist the parties in obtaining justice.”). Nebraska Territory (1866);116See Neb. Terr. Rev. Stat., Part II, § 1 (1866) (“The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. Its provisions, and all proceedings under it, shall be liberally construed, with a view to promote its object, and assist the parties in obtaining justice.”). Wyoming (1876);117See Wyo. Comp. Laws, ch. 13, tit. 1, § 2 (1876) (“The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. Its provisions, and all proceedings under it, shall be liberally construed, with a view to promote its object, and assist the parties in obtaining justice.”). Arizona Territory (1887);118See Ariz. Terr. Rev. Stat. tit. 60, ch. 5, § 2931 (1887) (“The rule of common law that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed shall not apply to the statutes of this territory, but such statutes and all proceedings under them shall be liberally construed with a view to effect their objects and to promote justice.”). Idaho Territory (1887);119See Idaho Terr. Rev. Stat. § 4 (1887) (“The rule of the common law that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to these Revised Statutes. The Revised Statutes establish the law of this Territory respecting the subjections to which they relate, and their provisions and all proceedings under them are to be liberally construed, with a view to effect their objects and promote justice.”). Utah Territory (1887);120See Utah Terr. Comp. Laws tit. 21, § 4 (1876) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed has no application to this code; all its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). and South Dakota (1903).121See S.D. Rev. Code § 2472 (1903) (“The rule of the common law that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed has no application to this code. This code establishes the law of this state respecting the subjects to which it relates, and its provisions are to be liberally construed with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”); S.D. Code of Civ. Pro. § 3 (The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. The code establishes the law of this state respecting the subjects to which it relates, and its provisions and all proceedings under it are to be liberally construed with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). Nevada may have done so as well. See Hall, supra note 19, at 753–54, 754 n.29 (citing “Nevada (1912)” for the proposition that “liberal construction statutes . . . have been passed . . . since 1890”).

B. State Anti-Lenity Statutes

State anti-lenity statutes—the phase three effort in this long, strange trip—came after these two other phases had begun in earnest. The precise origin of state anti-lenity statutes currently in place in a dozen states is murky. There are, however, glimpses that provide some insight, starting with mid-1800s codification efforts in Texas and, in particular, in New York.

1. Texas Codification in the Early 1850s

In 1854, less than a decade after it became a state, Texas began an effort to codify its criminal law and procedure.122See Joseph H. Pool, Bulk Revision of Texas Statutes, 39 Tex. L. Rev. 469, 470 (1961); see also Keith Carter, The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals, 11 Tex. L. Rev. 185, 185 (1933). The effort also included a code of civil law, which was not enacted. See id.; accord Pool, supra, at 470. The result of that effort is the Texas Penal Code of 1856, and a corresponding criminal procedural code, adopted effective January 1, 1857.123See Carter, supra note 122, at 185–86, 186 n.4. The Texas Penal Code included the following provision:

This Code, and every other law upon the subject of crime which may be enacted, shall be construed according to the plain import of the language in which it is written, without regard to the distinction usually made between the construction of penal laws and laws upon other subjects, and no person shall be punished for an offence which is not made penal by the plain import of the words of a law, upon the pretence that he has offended against its spirit.124Texas Penal Code tit. 1, art. 9 (1856). Although beyond the scope of this Article, the provision was amended at least twice within a few years after enactment. See Carter, supra note 122, at 187 (“The original article as adopted added the words, ‘upon the pretence that he has offended against its spirit’; but this clause was dropped in later revisions” [in Texas Penal Code Title 1, Ch. 1, Art. 9 (1879)]. In a further effort to restrict references to other laws it was provided in Article 4 that ‘When the definition of an offence made penal by the law of the state is merely defective, the rules of the common law shall apply and be resorted to, for the purpose of aiding in the interpretation of such penal enactment.’ But this seems to have been too great a restriction on the use of the common law to be satisfactory. In 1858 the article was changed to read: ‘The principles of the common law shall be the rule of construction when not in conflict with this code or the Code of Criminal Procedure or some other written statute of the State.’ In this form the article [as of 1933] has been retained.”).

The precise source of this text, and the rationale for it, is lost to time.125See Carter, supra note 122, at 186 n.124 (noting that “[t]he codes are said to have been mainly the work of James Willie,” who served as a Texas legislator and then as Texas Attorney General); id. at 186 (noting the early 1850s codification effort in Texas “was much influenced by the work of Edward Livingston,” who had crafted similar codes for Louisiana, although they were not enacted in Louisiana, and that “[t]he [Texas] codifiers acknowledged their indebtedness to Livingston, but failed to give detailed credit for their borrowings”); see also A. E. Wilkinson, Edward Livingston and the Penal Codes, 1 Tex. L. Rev. 25, 37–38, 38 n.13 (1923) (noting Willie supervised the publication of the codes, providing information about him and stating “[t]hese codes will remain a monument to [Willie’s] industry and fine legal capacity”). Although Nebraska enacted a nearly identical statute in 1873 that remains today,126See Neb. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 29-106 (West 2020) (requiring construction according to plain import of the language). no other state has a provision tracking this Texas statute. Texas courts construed this statute as negating the rule of lenity;127See, e.g., State v. Elliot, 34 Tex. 148, 150 (Tex. 1871) (after quoting this provision, noting that, in enacting it, “the law-making power wisely determined to reverse the rule” of lenity and stating that it and other statutory provisions “have greatly modified many of the harsh and reasonless special rules of the common law” and that the statute is “one of the most important modifications”); Murray v. State, 2 S.W. 757, 760–61 (Tex. Ct. App. 1886) (“We are aware that the rule of the common law which requires that penal statutes should be strictly construed is abrogated in this state, and that there is now no distinction recognized with us in construing statutes between those that are criminal or penal and those that are civil, but all are required to be construed alike liberally, with a view to carry out the intention of the legislature,” adding that “[a] general rule of construction is expressly provided” in this Texas Penal Code section), quoted with approval in Slack v. State, 136 S.W. 1073, 1078 (Tex. Crim. App. 1911). Nebraska courts, however, do not construe that state’s nearly identical statute as negating the rule of lenity.128See State v. Douglas, 388 N.W.2d 801, 803–04 (Neb. 1986) (quoting Neb. Rev. Stat. § 29-106 and stating “[i]t is a fundamental principle of statutory construction that a penal statute is to be strictly construed”). Although Texas retained this text for more than a century,129See, e.g., Vernon’s Tex. Penal Code tit. 1, ch. 1, art. 7 (1948); Vernon’s Tex. Penal Code tit. 1, ch. 1, art. 7 (1936); Tex. Penal Code tit. 1, ch. 1, art. 7 (1925); Tex. Penal Code tit. 1, ch. 1, art. 9 (1911); Tex. Penal Code tit. 1, ch. 1, art. 9 (1895). as discussed below, it repealed this provision in favor of a prototype anti-lenity statute effective in 1974.130See infra text accompanying notes 182–185.

2. New York Codification Efforts in the Mid-1800s

Although the Texas effort in the early 1850s was not broadly followed, the same cannot be said about the New York codification effort David Dudley Field II led at about this same time. Field championed state law reform through the codification of procedure and substantive law.131See, e.g., 1 Speeches, Arguments and Miscellaneous Papers of David Dudley Field 219 (A.P. Sprague ed., 1884) (containing letters, papers, codes, and addresses by Field on these topics from approximately forty years, beginning with a December 26, 1839, letter from Field to New York State Senator Gulian C. Verplank noting judicial reform would be would be the most important issue the legislature would consider in its next session). The effort initially focused on procedural codes, with the New York Commission on Practice and Pleadings submitting criminal and procedural codes to the New York Legislature in 1849.132See David Dudley Field, Introduction to the Completed Civil Code, in Field, supra note 131, at 324; see generally N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Report of a Code of Criminal Procedure (1849); N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Report of a Code of Civil Procedure (1849). Three substantive codes, sometimes referred to as the “codification of the common law,”133See David Dudley Field, Law Reform Tract No. 3: Codification of the Common Law, in Field, supra note 131, at 307–09; see generally Field, supra note 131 (starting with an 1847 essay, “What Shall Be Done With The Practice Of The Courts,” advocating codification of procedural rules, followed by various commission reports addressing codes of procedure from the late 1840s, and then reports and codes of common substantive law from 1852 to 1879). followed the procedural codes: (1) a political code (addressing state government “and the political rights and duties of its citizens”); (2) a civil code; and (3) a penal code.134See Field, Law Reform Tract No. 3, supra note 133, at 307–09 (setting forth this approach); David Dudley Field, First Report of the [New York] Code Commission, in Field, supra note 131, 309–14 (using this same approach); David Dudley Field, Second Report of the [New York] Code Commission, in Field, supra note 131, 315–16 (referencing political and penal codes); David Dudley Field, Final Report of the [New York] Code Commission, in Field, supra note 131, at 317 (“This body of substantive law [as distinguished from “[t]he Codes of Civil and Criminal Procedure”], the Legislature, by the Act of 1857, declared should be contained in the three codes—Political, Civil, and Penal—and to them the Commissioners of the Code have ever since devoted themselves.”); Field, Law Reform Tract No. 3, supra note 133, at 307, 308, 309 & n.* (proposing an act establishing a New York Commission to draft such codifications of the common law, which was then enacted in April 1857).

The New York Code Commission worked from 1857 to 1865 in developing these substantive codes.135See Field, Final Report, supra note 134, at 317. The Political Code (completed in 1859) and the Civil Code (completed in 1865) each contained “phase two” provisions, stating that statutes in derogation of the common law should not be strictly construed.136See N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Report of a Political Code § 1124 (1859) (“The rule that statutes in derogation of the common law are to be strictly construed, has no application to this Code.”); N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Report of a Civil Code § 2032 (1865) (“The rule that statutes in derogation of the common law are to be strictly construed has no application to this Code.”). A March 1864 draft of New York Penal Code, however, contained what would become the prototype state anti-lenity statute:

The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this Code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.137N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Draft of a Penal Code for the State of New York§ 10 (1864), quoted in Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.25. This March 1864 draft was circulated “for the purpose of obtaining suggestions which may aid the [Code] Commissioners in completing and perfecting the Code, for submission to the Legislature.” N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Draft of a Penal Code for the State of New York Preliminary Note (1864).

But why? What prompted the use of this text that sought to negate the rule of lenity? There is no clear answer. There are, however, some hints, both in the specific text used as well as in the commentary associated with the New York codification effort.

Although not identical, the text used is remarkably similar to how Wiltberger characterized the rule of lenity:

| Wiltberger | 1864 Draft New York Penal Code |

| “The rule that penal laws are to be construed strictly, is perhaps not . . .”138United States v. Wiltberger, 18 U.S. 76, 95 (1820). | “The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no . . .”139N.Y. Comm’rs on Practice and Pleadings, Draft of a Penal Code for the State of New York §10 (1864), quoted in Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.25. |

Adding the phrases “of the common law,” and using “penal statutes” (as opposed to “penal laws”) in the Draft New York Penal Code section is unsurprising, given that the codification effort sought to displace the common law in favor of a penal code.140Hall, supra note 19, at 753. And the code section, compared to Wiltberger, transposes “construed strictly” to “strictly construed.”141Id. at 753 n.25. But in other respects, the text is identical, including the oddly placed comma (or, perhaps, a comma missing after “The rule” at the beginning of the sentence). This textual similarity between Wiltberger and the Draft New York Penal Code section can be read to suggest that the codification effort was to negate the rule of lenity recognized in Wiltberger.

Additional insight comes from the limited, then-contemporaneous commentary contained in the New York Code Commission’s February 1865 “Introduction to the Completed Civil Code.”142Field, Introduction to the Completed Civil Code, supra note 132, at 323. This Introduction to the Civil Code had no reason to address the rule of lenity or the anti-lenity provision, which were applicable only to the Penal Code. The Introduction did, however, note the debate about the wisdom of codification of the law by the legislature, described as the “department of the government which alone has the prerogative of making and promulgating the laws, and law not so promulgated.”143Id. at 325. In noting, but dismissing, an objection that it was impossible for a code to anticipate all cases, the Introduction advocates for the supremacy of legislative enactment of a penal code when compared to the case-based common law:

There are certain departments of the law, of which we may affirm with perfect confidence, either that we have provided for every possible case, or that, when a new case arises, it is better that it should be provided for by new legislation, than by judicial decision. Thus, in respect to the Penal Code, it may be affirmed that every act for which punishment may be inflicted ought to be designated beforehand; that no man ought to be punished for an act not thus designated, and that if any act should be committed, for which society has prescribed no punishment, it may go for once unpunished, and a new law be made against other like acts in the future.144Id. at 327.

Rejecting an argument that codified law could not adapt to the future, the Introduction first negates the premise for the argument: “to say that a law is expansive, elastic, or accommodating, is as much as to say that it is no law at all.”145Id. at 331.

The Introduction then squarely addressed the argument “that it is better to let the Judges make the law as they go along, than to have the lawgiver make it beforehand.”146Id. The Introduction “affirmed with confidence, that a code, upon the theory on which this is framed, not only adapts itself to the present wants of society better than the existing common law, but that it contains within itself, in a greater degree, the elements of future progress.”147Id. at 333–34. The Introduction condemned the judiciary for being “unable, or, if able, unwilling, to make necessary amendments of the law” and being responsible for a “disjointed and comparatively inaccessible” common law.148Field, Introduction to the Completed Civil Code, supra note 132, at 334. Codification of the law, the Introduction added, would provide the legislature and the public a single, accessible, and condensed source of law, providing ready analysis to identify and fix any perceived defects or changes needed.149See id. The anti-strict-construction concept included in the proposed codes (here, the “phase two” Civil Code prohibition against strictly construing statutes in derogation of the common law) would prohibit courts from negating legislative enactments.150See id.; see also supra note 136 (quoting Civil and Political Code provisions).

Far more pointedly, the Introduction advocated a clear preference for codified law, not the common law, as the best vehicle for law reform and improvement:

In almost every instance where an improvement has been made in the laws, it has come from the Legislature. Had society been left to the discipline of the common law, whether it be called flexible or inflexible, the most cruel and bloody of criminal systems would still have shamed us; feudal tenures with all their burdensome incidents would have remained; land would have been inalienable without livery of seizin, and wives would have had only the rights which a barbarous age conceded them. . . . So far as the choice lies between law to be made by the Legislature and law to be made by the judiciary, there cannot be a doubt that, whatever may be the determination elsewhere, the people of this State prefer that theirs shall be made by those whom they elect as legislators, rather than by those whose function it is, according to the theory of the Constitution, to administer the laws as they find them. Hence, the idea of a code has taken such hold of our people that they have made provision for it by their organic law.151Field, Introduction to the Completed Civil Code, supra note 132, at 335, 337–38.

This Introduction makes plain that the New York effort in the mid-1800s included a strong preference for codification of the law by legislative enactments, not the common law identified in judicial decisions. It also reflects a profound concern about changes in the law coming from judicial decisions (based on the proposition that courts are to apply the law as they find it), preferring instead the legislative process of codification and amendment. And the Introduction advocates that the codification effort should prevent courts from negating legislation. Although it is unknown whether this rationale in New York prompted the state anti-lenity statutes enacted in other states, the anti-lenity text in this draft 1864 New York Penal Code would become the prototype anti-lenity statute.

3. State Anti-Lenity Enactments in the 1800s

Despite this New York codification effort, including the development of what would become the prototype state anti-lenity statute, Oregon was the first state to enact an anti-lenity statute using this text. In 1864, Oregon enacted a Criminal Code that included the following anti-lenity statute:

The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code, but all its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.152Or. Crim. Code tit. 2, ch. 14, § 787 (1864).

This enactment is substantively identical, including the oddly placed comma, to the anti-lenity provision in the March 1864 New York Draft Penal Code.153The differences, when compared to the draft 1864 New York Penal Code, are that New York capitalized “Code” and broke the provision into two sentences (meaning the “but” is removed and “All” is capitalized). Compare id. with Hall, supra note 19, at 753 n.25. Nearly identical state anti-lenity enactments followed in California (1872);154See Cal. Penal Code § 4 (1872) (“The rule of the common law, that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this Code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). Dakota Territory (1875 in a different form,155See Dakota Terr. Code of Crim. Proc. Tit. 11, ch. 13, § 602 (1875) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this Code. This Code establishes the law of this territory respecting the subjects to which it relates, and its provisions and all proceedings under it are to be liberally construed with a view a view to promote its objects, and in furtherance of justice.”). and then nearly identically in 1877);156See Dakota Terr. Penal Code, ch. 1, § 10 (1877) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). Utah Territory (1876);157See Utah Terr. Comp. Laws tit. 21, § 4 (1876) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed has no application to this code; all its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). New York (1881);158See N.Y. Penal Code, ch. 676, § 11 (1881) (“The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this Code or any of the provisions thereof, but all such provisions must be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to promote justice and effect the objects of the law.”). Minnesota (1889);159See Minn. Penal Code § 9 (1889) (“The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this code or any of the provisions thereof, but all such provisions must be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to promote justice and effect the objects of the law.”). The Minnesota enactment was part of a criminal codification that “consisted largely of adaptations of New York’s 1881 Penal Code.” Bradford Colbert & Frances Kern, A Brief History of the Development of Minnesota’s Criminal Law, 39 WM. Mitchell L. Rev. 1441, 1445 (2013). Arizona Territory (1887);160See Ariz. Terr. Penal Code § 5 (1887) (“The rule of the common law, that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its object and to promote justice.”). Oklahoma (1890);161See Okla. Stat., ch. 25, art. 1, § 10 (1890) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). Montana (1895);162See Mont. Pol. Code § 4 (1895) (“The rule of the common law, that statutes in derogation thereof are to be strictly construed, has no application to this Code. The Code establishes the law of this State respecting the subjects to which it relates, and its provisions and all proceedings under it are to be liberally construed, with a view to effect its objects and promote justice.”). Montana’s 1895 codification originated with the New York Field Codes. See Angelica Gonzalez, Comment, The Rule of Lenity in the State of Montana: Is There Lenity?, 79 Mont. L. Rev. 205, 209 & n.31 (2018) (citing Andrew P. Morriss, “This State Will Soon Have Plenty of Laws”—Lessons from One Hundred Years of Codification in Montana, 56 Mont. L. Rev. 359, 366 (1995)). North Dakota (1895)163See N.D. Penal Code, ch. 1, § 10 (1895) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and to promote justice.”). and South Dakota (1903).164See S.D. Penal Code, ch. 1, § 10 (1903) (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. All its provisions are to be construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects and promote justice.”); Id. at ch. 15, § 636 (“The rule of the common law that penal statutes are to be strictly construed, has no application to this code. This code establishes the law of this state respecting the subjects to which it relates, and its provision and all its proceedings under it are to be liberally construed according to the fair import of their terms, with a view to effect its objects, and in furtherance of justice.”). By 1903, there were ten states or territories with nearly identical anti-lenity statutes. Although the reasons for the enactment of these provisions is lost to time, some information is available for more recent state anti-lenity legislation.

4. State Anti-Lenity Legislation in the 1900s

State anti-lenity legislation efforts continued in the twentieth century: (1) four states (Michigan,165See Mich. Penal Code § 17115-2 (1931) (“The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed shall not apply to this act or any of the provisions thereof. All provisions of this act shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to promote justice and to effect the objects of the law.”). Delaware,166See Del. Crim. Code, ch. 2, § 203 (1973) (“The general rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this Criminal Code, but the provisions herein must be construed according to the fair import of their terms to promote justice and effect the purposes of the law, as stated in section 201 of this Criminal Code.”). New Hampshire,167See N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. Tit. 62, ch. 625, § 625:3 (1973) (“The rule that penal statutes are to be strictly construed does not apply to this code. All provisions of this code shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms and to promote justice.”). and Texas168See Tex. Penal Code Ann., tit. 1, ch. 1, § 1.05(a) (West 1973) (“The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this code. The provisions of this code shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms, to promote justice and effect the objectives of the code.”). Although beyond the scope of this Article, by 1978 the country of Liberia had adopted this same anti-lenity statute. See Penal Code of Liber., tit. 26, pt. 1, ch.1, § 1.2 (“The rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this title, but the provisions herein shall be construed according to the fair import of their terms and when the language is susceptible of differing constructions it shall be interpreted to further the general purposes stated in Section 1.1 and the special purposes of the particular provisions involved.”). The statute was a product of the Liberian Codification Project, which began in 1952. See Liber. Code of Laws Revised, vol. 1, xiii (1973) (Forward by James A. A. Pierre, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of Liberia). Guam also adopted a statute that, although using different text, incorporates an anti-lenity directive. See 1 Guam Code Ann., ch. 7, § 700 (2018) (“Use of Common Law Rules of Construction”) (“Unless a different intent appears in law, or in applicable court decisions, or in this Code, the common law rules of construction shall apply to the interpretation of this Code and to all other laws of Guam; provided, that, common law rules that statutes in derogation of the common law, and penal statutes shall be strictly construed shall not apply.”).

a. Enactments

No relevant legislative history was located for Michigan’s anti-lenity statute enacted in 1931. The Delaware enactment was part of a recodification effort undertaken following the promulgation of the Model Penal Code in 1962.169See Del. Crim. Code, pg. iii (1973) (introductory comment). This legislative history for Delaware’s enactment was made possible only with the able, prompt, and incredibly thorough information provided by Galen Wilson, Senior Law Librarian & Self-Help Center Coordinator, State Law Library, Wilmington, DE; John F. Brady, Esq., Law Librarian, Sussex County Law Library, Georgetown, DE, and Sara Zimmerman, Delaware Legislative Librarian & Research Analyst. Within a very short time, Mr. Wilson responded to a “cold” email inquiry by the author by providing information, including much of the information cited here, and an introduction to Ms. Zimmerman, and Mr. Brady called the author with additional information and background (including correcting an error about the date for Delaware’s efforts discussed here). Ms. Zimmerman, again in lightning speed, provided the relevant excerpt from the 1967 Governor’s Committee for Revision of the Criminal Code. Their doing so was above and beyond the call of duty and is much appreciated by the author. By late 1967, a criminal code revision committee submitted a draft Delaware Criminal Code to that state’s legislature.170Id. at iv. That draft included a prototype anti-lenity statute, which was then enacted.171See Del. Crim. Code § 6 (Governor’s Comm. for Revision of the Crim. L., Proposed Code 1967) (“Principles of construction”) (“The general rule that a penal statute is to be strictly construed does not apply to this Criminal Code, but the provisions herein must be construed according to the fair import of their terms to promote justice and effect the purposes of the law, as stated in section 5 of this Criminal Code.”). The Committee’s commentary for the provision stated: