Introduction

The dystopian novel is a powerful literary genre. It has given us such masterpieces as Nineteen Eighty-Four,1George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four: A Novel (1949). Brave New World,2Aldous Huxley, Brave New World (1932). Fahrenheit 451,3Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (1953). and Animal Farm.4George Orwell, Animal Farm: A Fairy Story (1945). Though these novels often shed light on some of the risks that contemporary society faces and the zeitgeist of the time when they were written, they almost always systematically overshoot the mark (whether intentionally or not) and severely underestimate the radical improvements commensurate with the technology (or other causes) that they fear. Nineteen Eighty-Four, for example, presciently saw in 1949 the coming ravages of communism, but it did not guess that markets would prevail, allowing us all to live freer and more comfortable lives than any preceding generation.5See, e.g., Matt Ridley, The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves 12 (2010) (noting that the present generation has access to more resources and opportunities than any previous generation). Fahrenheit 451 accurately feared that books would lose their monopoly as the foremost medium of communication, but it completely missed the unparalleled access to knowledge that today’s generations enjoy.6Obviously this has been enabled by the internet and the emergence of online knowledge sources, such as Google Search and Wikipedia, which have both expanded the extent of the world’s information and brought it—in usable form—into the palm of every consumer. And while Animal Farm portrayed a metaphorical world where increasing inequality is inexorably linked to totalitarianism and immiseration, global poverty has reached historic lows in the twenty-first century,7See, e.g., Max Roser, Global Economic Inequality, Our World in Data, https://perma.cc/9U92-VMWD (showing that the Gini coefficient of global inequality declined from 68.7 to 64.9 between 2003 and 2013). This data is sourced from Tomáš Hellebrandt & Paolo Mauro, The Future of Worldwide Income Distribution 13 (Peterson Inst. for Int’l Econ., Working Paper No. 15-7, 2015) (“Taking the global distribution of income as a whole, the Gini coefficient was 64.9 in 2013, down from 68.7 in 2003.”). and this is likely also true of global inequality.8World Bank, Summary of Chapter 1: Ending Global Poverty, World Bank (Sept. 19, 2018), https://perma.cc/A94M-VDGP (“In 2015, an estimated 736 million people were living below the international poverty line of $1.90 in 2011 purchasing power parity. This is down from 1.9 billion people in 1990. Over the course of a quarter-century, 1.1 billion people (on net) have escaped poverty and improved their standard of living.”). In short, for all their literary merit, dystopian novels appear to be terrible predictors of the quality of future human existence. The fact that popular depictions of the future often take the shape of dystopias is more likely reflective of the genre’s entertainment value than of society’s impending demise.9See, e.g., Devon Maloney, Why Is Science Fiction So Afraid of the Future?, The Verge (Nov. 6, 2017, 10:41 AM), https://perma.cc/T7FE-YDSP (“When tangible signs of humanity’s collapse are omnipresent, it can feel impossible to imagine humans surviving the next hundred years, let alone emerging into a utopic technological wonderland in the 26th century. This goes for consumers just as much as creators; truly imaginative futures like that of Valerian [and the City of a Thousand Planets], for example, bomb with audiences for being too far-flung without real critical purpose. They’re untethered and tone-deaf to the existential issues we’re facing in this very instant.” (emphasis omitted)); see also Joe Queenan, From Insurgent to Blade Runner: Why Is the Future on Film Always So Grim?, The Guardian (Mar. 19, 2015, 2:51 PM), https://perma.cc/A764-JEQU (“Why do films such as The Hunger Games and Elysium and Dredd always depict a world where everyone is miserable? . . . [M]aybe it’s because mature adults are envious of their grandchildren, and figure that if they themselves are not going to be around to enjoy the future, nobody else should enjoy it either. This isn’t very nice, but it’s exactly the way the middle-aged mind operates: après moi, le déluge, as Louis XVI’s granddad once put it.”).

But dystopias are not just a literary phenomenon; they are also a powerful force in policy circles. For example, in the early 1970s, the so-called Club of Rome published an influential report titled The Limits to Growth.10Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers & William W. Behrens III, The Limits to Growth (1972) (a report for The Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind). The report argued that absent rapid and far-reaching policy shifts, the planet was on a clear path to self-destruction:

If the present growth trends in world population, industrialization, pollution, food production, and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next one hundred years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.11Id. at 23.

Halfway through the authors’ 100-year timeline, however, available data suggests that their predictions were way off the mark. While the world’s economic growth has continued at a breakneck pace,12See GDP Per Capita, 1820 to 2018, Our World in Data, https://perma.cc/YP24-YNQM. extreme poverty,13See Max Roser & Esteban Ortiz-Ospina, Global Extreme Poverty, Our World in Data, https://perma.cc/5CDA-K75Z. famine,14See Joe Hasell & Max Roser, Famines, Our World in Data, https://perma.cc/8529-5AGD. and the depletion of natural resources15See Andrew McAfee, More from Less: The Surprising Story of How We Learned to Prosper Using Fewer Resources—and What Happens Next 1 (2019) (“For just about all human history our prosperity has been tightly coupled to our ability to take resources from the earth. So as we became more numerous and prosperous, we inevitably took more: more minerals, more fossil fuels, more land for crops, more trees, more water, and so on. But not anymore. In recent years, we’ve seen a different pattern emerge: the pattern of more from less.”). have all decreased tremendously.

For all its inaccurate and misguided predictions, dire tracts such as The Limits to Growth perhaps deserve some of the credit for the environmental movements that followed. But taken at face value, the dystopian future along with the attendant policy demands put forward by works like The Limits to Growth would have had cataclysmic consequences for, apparently, extremely limited gain. The policy incentive is to strongly claim impending doom. There’s no incentive to suggest “all is well,” and little incentive even to offer realistic, caveated predictions.

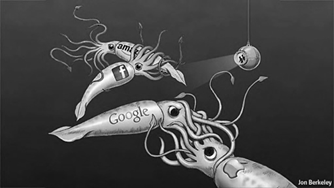

As we argue in this Article, antitrust scholarship and commentary is also afflicted by dystopian thinking. Today, antitrust pessimists have set their sights predominantly on the digital economy—“big tech” and “big data”—alleging a vast array of potential harms. Scholars have argued that the data created and employed by the digital economy produces network effects that inevitably lead to tipping and more concentrated markets.16See, e.g., Maurice E. Stucke & Allen P. Grunes, Debunking the Myths over Big Data and Antitrust, CPI Antitrust Chronicle, May 2015, at 2 (attempting to dispel the “myth[]” that competition can prosper in data-driven markets without far-reaching government intervention); see also Nathan Newman, Search, Antitrust, and the Economics of the Control of User Data, 31 Yale J. on Reg. 401, 453 (2014) (“The complex challenge of displacing a dominant incumbent such as Google in information-related markets should serve as a lesson that problems of network effects, technology lock-in, and the speed with which a dominant player can take control of a sector, all call for earlier intervention in technology markets. It would be better for regulators to maintain an open environment for innovation early, rather than depend on a post-facto, drawn-out court fight to displace a monopolist.”). In other words, firms will allegedly accumulate insurmountable data advantages and thus thwart competitors for extended periods of time. Some have gone so far as to argue that this threatens the very fabric of western democracy.17See, e.g., Tim Wu, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age 14 (2018) (“We have managed to recreate both the economics and politics of a century ago—the first Gilded Age—and remain in grave danger of repeating more of the signature errors of the twentieth century. As that era has taught us, extreme economic concentration yields gross inequality and material suffering, feeding an appetite for nationalistic and extremist leadership. Yet, as if blind to the greatest lessons of the last century, we are going down the same path. If we learned one thing from the Gilded Age, it should have been this: The road to fascism and dictatorship is paved with failures of economic policy to serve the needs of the general public.”); id. at 21 (“The most visible manifestations of the consolidation trend sit right in front of our faces: the centralization of the once open and competitive tech industries into just a handful of giants: Facebook, Amazon, Google, and Apple. The power that these companies wield seems to capture the sense of concern we have that the problems we face transcend the narrowly economic. Big tech is ubiquitous, seems to know too much about us, and seems to have too much power over what we see, hear, do, and even feel. It has reignited debates over who really rules, when the decisions of just a few people have great influence over everyone. Their power feels like ‘a kingly prerogative, inconsistent with our form of government’ in the words of Senator John Sherman, for whom the Sherman Act is named.”). Other commentators have voiced fears that companies may implement abusive privacy policies to shortchange consumers.18See, e.g., Tommaso Valletti, Chief Economist, Directorate-General for Competition, Keynote Address at CRA Annual Brussels Conference: Economic Developments in Competition Policy (Dec. 5, 2018). It has also been said that the widespread adoption of pricing algorithms will almost inevitably lead to rampant price discrimination and algorithmic collusion.19See Ariel Ezrachi & Maurice E. Stucke, Virtual Competition: The Promise and Perils of the Algorithm-Driven Economy 36–37 (2016) (“We note how Big Data and Big Analytics—in increasing the speed of communicating price changes, detecting any cheating or deviations, and punishing such deviations—can provide new and enhanced means to foster collusion.”). Indeed, “pollution” from data has even been likened to the environmental pollution that spawned The Limits to Growth: “If indeed ‘data are to this century what oil was to the last one,’ then—[it’s] argue[d]—data pollution is to our century what industrial pollution was to the last one.”20Omri Ben-Shahar, Data Pollution, 11 J. Legal Analysis 104, 106 (2019).

Some scholars have drawn explicit parallels between the emergence of the tech industry and famous dystopian novels. Professor Shoshana Zuboff, for instance, refers to today’s tech giants as “Big Other.”21See Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power 376 (2019) (“I now name the apparatus Big Other: it is the sensate, computational, connected puppet that renders, monitors, computes, and modifies human behavior. Big Other combines these functions of knowing and doing to achieve a pervasive and unprecedented means of behavioral modification. Surveillance capitalism’s economic logic is directed through Big Other’s vast capabilities to produce instrumentarian power, replacing the engineering of souls with the engineering of behavior.” (emphasis omitted)). In an article called “Only You Can Prevent Dystopia,” one New York Times columnist surmised:

The new year is here, and online, the forecast calls for several seasons of hell. Tech giants and the media have scarcely figured out all that went wrong during the last presidential election—viral misinformation, state-sponsored propaganda, bots aplenty, all of us cleaved into our own tribal reality bubbles—yet here we go again, headlong into another experiment in digitally mediated democracy.

I’ll be honest with you: I’m terrified . . . There’s a good chance the internet will help break the world this year, and I’m not confident we have the tools to stop it.22Farhad Manjoo, Only You Can Prevent Dystopia, N.Y. Times (Jan. 1, 2020), https://perma.cc/KN7U-XYHC.

Parallels between the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and the power of large digital platforms were also plain to see when Epic Games launched an antitrust suit against Apple and its App Store in August 2020.23Epic Games antitrust complaint starts with the following ominous sentences: “In 1984, the fledgling Apple computer company released the Macintosh—the first mass-market, consumer-friendly home computer. The product launch was announced with a breathtaking advertisement evoking George Orwell’s 1984 that cast Apple as a beneficial, revolutionary force breaking IBM’s monopoly over the computing technology market. Apple’s founder Steve Jobs introduced the first showing of the 1984 advertisement by explaining, ‘it appears IBM wants it all. Apple is perceived to be the only hope to offer IBM a run for its money . . . . Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?’ [ ] Fast forward to 2020, and Apple has become what it once railed against: the behemoth seeking to control markets, block competition, and stifle innovation. Apple is bigger, more powerful, more entrenched, and more pernicious than the monopolists of yesteryear. At a market cap of nearly $2 trillion, Apple’s size and reach far exceeds that of any technology monopolist in history.” Complaint at 1, Epic Games, Inc. vs. Apple, Inc., 4:20-cv-05640 (N.D. Cal. Aug. 13, 2020). Indeed, Epic Games released a short video clip parodying Apple’s famous “1984” ad (which upon its release was itself widely seen as a critique of the tech incumbents of the time).24Epic Games, Nineteen Eighty-Fortnite – #FreeFortnite, YouTube (Aug. 13, 2020), https://perma.cc/78SF-KY5X.

Similarly, a piece in the New Statesman, titled “Slouching Towards Dystopia: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism and the Death of Privacy,” concluded that: “Our lives and behaviour have been turned into profit for the Big Tech giants—and we meekly click ‘Accept.’ How did we sleepwalk into a world without privacy?”25John Naughton, Slouching Towards Dystopia: The Rise of Surveillance Capitalism and the Death of Privacy, New Statesman (Feb. 26, 2020), https://perma.cc/S67W-HXTC.

Finally, a piece published in the online magazine Gizmodo asked a number of experts whether we are “already living in a tech dystopia.”26Daniel Kolitz, Are We Already Living in a Tech Dystopia?, Gizmodo (Aug. 24, 2020, 8:00 AM), https://perma.cc/V3YZ-5C4B. Some of the responses were alarming, to say the least:

I’ve started thinking of some of our most promising tech, including machine learning, as like asbestos: . . . it’s really hard to account for, much less remove, once it’s in place; and it carries with it the possibility of deep injury both now and down the line.

. . . .

We live in a world saturated with technological surveillance, democracy-negating media, and technology companies that put themselves above the law while helping to spread hate and abuse all over the world.

Yet the most dystopian aspect of the current technology world may be that so many people actively promote these technologies as utopian.27Id. (quoting Professor Jonathan Zittrain and Professor David Golumbia).

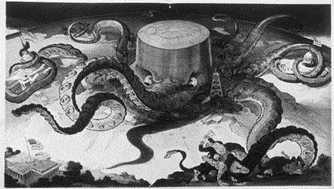

Antitrust pessimism is not a new phenomenon, and antitrust enforcers and scholars have long been fascinated with—and skeptical of—high tech markets. From early interventions against the champions of the Second Industrial Revolution (oil, railways, steel, etc.)28See United States v. U.S. Steel Corp., 251 U.S. 417 (1920); Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911); United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. 290 (1897). through the mid-twentieth century innovations such as telecommunications and early computing (most notably the RCA, IBM, and Bell Labs consent decrees in the US)29See, e.g., In re Int’l Bus. Mach. Corp., 618 F.2d 923 (2d Cir. 1980); see also Martin Watzinger, Thomas A. Fackler, Markus Nagler & Monika Schnitzer, How Antitrust Enforcement Can Spur Innovation: Bell Labs and the 1956 Consent Decree, 12 Am. Econ. J. Econ. Pol’y 328, 328–29 (2020). to today’s technology giants, each wave of innovation has been met with a rapid response from antitrust authorities, copious intervention-minded scholarship, and waves of pessimistic press coverage.30See Dirk Auer & Nicolas Petit, Two Systems of Belief About Monopoly: The Press vs. Antitrust, 39 Cato J. 99, 99 (2019). This is hardly surprising given that the adoption of antitrust statutes was in part a response to the emergence of those large corporations that came to dominate the Second Industrial Revolution (despite the numerous radical innovations that these firms introduced in the process).31See Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Origins of Antitrust: Rhetoric vs. Reality, Regulation, Fall 2019, at 26, 29-30. Especially for unilateral conduct issues, it has long been innovative firms that have drawn the lion’s share of cases, scholarly writings, and press coverage.

Underlying this pessimism is a pervasive assumption that new technologies will somehow undermine the competitiveness of markets, imperil innovation, and entrench dominant technology firms for decades to come. This is a form of antitrust dystopia. For its proponents, the future ushered in by digital platforms will be a bleak one—despite abundant evidence that information technology and competition in technology markets have played significant roles in the positive transformation of society.32See, e.g., Ridley, supra note 5, at 12; see generally Steven Pinker, Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress (2018). This tendency was highlighted by economist Ronald Coase:

[I]f an economist finds something—a business practice of one sort or another—that he does not understand, he looks for a monopoly explanation. And as in this field we are very ignorant, the number of ununderstandable practices tends to be rather large, and the reliance on a monopoly explanation, frequent.33R. H. Coase, Industrial Organization: A Proposal for Research, in 3 Policy Issues and Research Opportunities in Industrial Organization 59, 67 (Victor R. Fuchs ed., 1972).

“The fear of the new—and the assumption that ‘ununderstandable practices’ emerge from anticompetitive impulses and generate anticompetitive effects—permeates not only much antitrust scholarship, but antitrust doctrine as well.”34Geoffrey A. Manne, Error Costs in Digital Markets, in The Global Antitrust Institute Report on the Digital Economy 33, 83 (Joshua D. Wright & Douglas H. Ginsburg eds., 2020) (footnote omitted). While much antitrust doctrine is capable of accommodating novel conduct and innovative business practices, antitrust law—like all common law-based legal regimes—is inherently backward looking: it primarily evaluates novel arrangements with reference to existing or prior structures, contracts, and practices, often responding to any deviations with “inhospitality.”35See Alan J. Meese, Price Theory, Competition, and the Rule of Reason, 2003 U. Ill. L. Rev. 77, 124 (2003) (describing the “inhospitality tradition of antitrust” as “extreme hostility toward any contractual restraint on the freedom of individuals or firms to engage in head-to-head rivalry”). For a discussion of the “inhospitality tradition” and its problematic consequences generally, see Oliver E. Williamson, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting 370–73 (1985), and Meese, supra. As a result, there is a built-in “nostalgia bias” throughout much of antitrust that casts a deeply skeptical eye upon novel conduct.

“The upshot is that antitrust scholarship often emphasizes the risks that new market realities create for competition, while idealizing the extent to which previous market realities led to procompetitive outcomes.”36Manne, supra note 34, at 83. Against this backdrop, our Article argues that the current wave of antitrust pessimism is premised on particularly questionable assumptions about competition in data-intensive markets.

Part I lays out the theory and identifies the sources and likely magnitude of both the dystopia and nostalgia biases. Having examined various expressions of these two biases, the Article argues that their exponents ultimately seek to apply a precautionary principle within the field of antitrust enforcement, made most evident in critics’ calls for authorities to shift the burden of proof in a subset of proceedings.

Part II discusses how these arguments play out in the context of digital markets. It argues that economic forces may undermine many of the ills that allegedly plague these markets—and thus the case for implementing a form of precautionary antitrust enforcement. For instance, because data is ultimately just information, it will prove exceedingly difficult for firms to hoard data for extended periods of time. Instead, a more plausible risk is that firms will underinvest in the generation of data. Likewise, the main challenge for digital economy firms is not so much to obtain data, but to create valuable goods and hire talented engineers to draw insights from the data these goods generate. Recent empirical findings suggest, for example, that data economy firms don’t benefit as much as often claimed from data network effects or increasing returns to scale.

Part III reconsiders the United States v. Microsoft Corp.3784 F. Supp. 2d 9 (D.D.C. 1999), aff’d in part and rev’d in part, 253 F.3d 34 (D.C. Cir. 2001). antitrust litigation—the most important precursor to today’s “big tech” antitrust enforcement efforts—and shows how it undermines, rather than supports, pessimistic antitrust thinking. It shows that many of the fears that were raised at the time didn’t transpire (for reasons unrelated to antitrust intervention). Rather, pessimists missed the emergence of key developments that greatly undermined Microsoft’s market position, and greatly overestimated Microsoft’s ability to thwart its competitors. Those circumstances—particularly revolving around the alleged “applications barrier to entry”—have uncanny analogues in the data markets of today. We thus explain how and why the Microsoft case should serve as a cautionary tale for current enforcers confronted with dystopian antitrust theories.

In short, the Article exposes a form of bias within the antitrust community. Unlike entrepreneurs, antitrust scholars and policy makers often lack the imagination to see how competition will emerge and enable entrants to overthrow seemingly untouchable incumbents. New technologies are particularly prone to this bias because there is a shorter history of competition to go on and thus less tangible evidence of attrition in these specific markets. The digital future is almost certainly far less bleak than many antitrust critics have suggested and yet the current swath of interventions aimed at reining in “big tech” presume. This does not mean that antitrust authorities should throw caution to the wind. Instead, policy makers should strive to maintain existing enforcement thresholds, which exclude interventions that are based solely on highly speculative theories of harm.

I. The Precautionary Principle and Antitrust

Much of the momentum to reform antitrust enforcement for the twenty-first century is firmly rooted in the precautionary principle. The precautionary principle can be thought of as a form of cost-benefit analysis that gives significantly more weight to potential harms than potential benefits. In its most extreme form, the precautionary principle might even give an infinite weight to potential harms, implying that no action should be taken unless it is certain that it will cause no harm at all, however large its countervailing benefits may be.38See Julian Morris, Rethinking Risk and the Precautionary Principle 1 (2000) (“Whilst there are many definitions of the precautionary principle (hereinafter, PP), it is worth distinguishing two broad classes: first, the Strong PP, which says basically, take no action unless you are certain that it will do no harm; and second, the Weak PP, which says that lack of full certainty is not a justification for preventing an action that might be harmful.”).

Precautionary reasoning is often, but not always, reserved for situations that involve an element of uncertainty rather than mere risk.39See Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Rupert Read, Raphael Douady, Joseph Norman & Yaneer Bar-Yam, The Precautionary Principle (with Application to the Genetic Modification of Organisms) 4 (NYU Sch. of Eng’g Working Paper Series, 2014) (“In some classes of complex systems, controlled experiments cannot evaluate all of the possible systemic consequences under real-world conditions. In these circumstances, efforts to provide assurance of the ‘lack of harm’ are insufficiently reliable. This runs counter to both the use of empirical approaches (including controlled experiments) to evaluate risks, and to the expectation that uncertainty can be eliminated by any means.”). As economist Frank Knight observed, risk describes situations where the outcome of an action is unknown, but where the probabilities and harms associated with that action are known.40Frank H. Knight, Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit 19–20 (1921) (“Uncertainty must be taken in a sense radically distinct from the familiar notion of Risk, from which it has never been properly separated. The term ‘risk,’ as loosely used in everyday speech and in economic discussion, really covers two things which, functionally at least, in their causal relations to the phenomena of economic organization, are categorically different . . . . The essential fact is that ‘risk’ means in some cases a quantity susceptible of measurement, while at other times it is something distinctly not of this character; and there are far-reaching and crucial differences in the bearings of the phenomenon depending on which of the two is really present and operating . . . . It will appear that a measurable uncertainty, or ‘risk’ proper, as we shall use the term, is so far different from an unmeasurable one that it is not in effect an uncertainty at all. We shall accordingly restrict the term ‘uncertainty’ to cases of the non-quantitative type.”). Risk thus lends itself to precise expected gain computations. Conversely, uncertainty is present when the payoffs or probabilities of an action are unknown.41Id. Precise expected gain calculations are thus impossible. The precautionary principle has often been cited as a method of dealing with uncertainty.42See, e.g., Cass R. Sunstein, The Paralyzing Principle, 25 Regulation, Winter 2002, at 32, 36 (“In a situation of uncertainty, when existing knowledge does not permit regulators to assign probabilities to outcomes, some argue that people should follow the ‘Maximin’ Principle: Choose the policy with the best worst-case outcome.”). Proponents of mild versions of the precautionary principle thus tend to circumscribe its application to situations of uncertainty, whereas proponents of stronger versions of the principle also urge authorities to apply it to situations of risk.43See, e.g., Taleb et al., supra note 39, at 1 (“Traditional decision-making strategies focus on the case where harm is localized and risk is easy to calculate from past data. Under these circumstances, cost-benefit analyses and mitigation techniques are appropriate. The potential harm from miscalculation is bounded. On the other hand, the possibility of irreversible and widespread damage raises different questions about the nature of decision making and what risks can be reasonably taken. This is the domain of the [precautionary principle].”).

The distinction between risk and uncertainty is critical. It is widely accepted that embracing localized risk (properly defined) is not just acceptable, but eminently desirable.44See id. Driving a car may increase a person’s risk of mortality compared to sitting at home, but the benefits probably outweigh the costs. More importantly, when only risk is involved, good and bad outcomes can and should be weighed against each other, accounting for both sides of the coin. There is thus no obvious reason to reject cost-benefit analysis as a basis for risky decision-making.

Real questions—and ensuing policy debates—arise in situations of uncertainty.45Although the line between risk and uncertainty is blurry. Indeed, there is no such thing as absolute scientific certainty, because scientific statements must, by definition, be falsifiable. For a discussion of science and falsification, see Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery 312–16 (1959). See also Hilary Putnam, The ‘Corroboration’ of Theories, in The Philosophy of Science 126–27 (Richard Boyd, Philip Gasper & J.D. Trout eds., 1991) (arguing that theories should not automatically be rejected because they have not been falsified in particular instances). Uncertainty gives rise to two interrelated policy questions. First, how should decisionmakers account for hypothetical costs and benefits (although the latter side of the equation is often ignored by critics)? Second, who should bear the burden of proving which outcomes are plausible or most likely?

Undergirding these two questions is a fear that uncertainty may conceal harmful, fat-tailed outcomes (i.e., low probability/high impact events, sometimes referred to as “Black Swans”).46See Nassim Nicholas Taleb, The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable xviii (2007). For instance, the seemingly never-ending policy debates surrounding the use of genetically modified organisms for human consumption have this characteristic. On one side of the debate, commentators cite significant possible risks, while proponents point towards a veritable cornucopia of potential upsides.47See, e.g., Taleb et al., supra note 39; Mark Spitznagel & Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Another ‘Too Big to Fail’ System in G.M.O.s, N.Y. Times (July 13, 2015), https://perma.cc/AJ88-NWJP. But see Ronald Bailey, GMO Alarmist Nassim Taleb Backs Out of Debate. I Refute Him Anyway, Reason (Feb. 19, 2016, 1:30 PM), https://perma.cc/39VB-FFR4. Whatever one’s views on this matter, the key challenge for policy makers clearly lies in weighing harms (and benefits) that are often hypothetical against tangible upsides (and drawbacks).

In order to address these questions, policy makers and scholars have put forward various iterations of the precautionary principle.48See, e.g., Cass R. Sunstein, Beyond the Precautionary Principle, 151 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1003, 1014 (2003). At one end of the spectrum, proponents argue that the precautionary principle should preclude any activity that is not proven to be safe (though, taken literally, this command is impossible), and that parties undertaking an activity should have the burden of proving its safety.49Id. (describing the “Prohibitory Precautionary Principle”). On the other side, proponents argue that absence of scientific uncertainty is not sufficient to preclude regulation and that the burden of proving potential risks should fall upon those who seek to impose precautionary measures.50Id. (describing the “Nonpreclusion Precautionary Principle”).

The goal of this Article is certainly not to provide an exhaustive survey of these various embodiments of the precautionary principle, and much less to argue in favor of one, or none of them. Instead, we wish to point out that precautionary principle-type reasoning has increasingly permeated antitrust policy discourse.51See, e.g., Aurelien Portueuse, The Rise of Precautionary Antitrust: An Illustration with the EU Google Android Decision, Competition Pol’y Int’l (Nov. 17, 2019), https://perma.cc/TE97-4NJ5 (“To a non-negligible extent, the Google Android decision illustrates the coming to the fore of a form of precautionary antitrust whereby, even without proven consumer harm, competition authorities are not barred from ex ante intervention to protect what can be seen as irreversible damage—an ‘effective competitive structure’—enabling competitors to emerge and compete.” (footnote omitted)).

This is best evidenced by two phenomena, which we refer to as “Antitrust Dystopia” and “Antitrust Nostalgia.” Antitrust Dystopia is the pessimistic tendency for competition scholars and enforcers to assert that novel business conduct will cause technological advances to have unprecedented, anticompetitive consequences. This is almost always grounded in the belief that “this time is different”—that, despite the benign or positive consequences of previous, similar technological advances, this time those advances will have dire, adverse consequences absent enforcement to stave off abuse.

Complementary to Antitrust Dystopia is Antitrust Nostalgia: the biased assumption—often built into antitrust doctrine itself—that change is bad. Antitrust Nostalgia holds that because a business practice has seemingly benefited competition before, changing it will harm competition going forward. Thus, antitrust enforcement is often skeptical of, and triggered by, various deviations from status quo conduct and relationships (i.e., “non-standard” business arrangements) when, to a first approximation (and at the very least in digital marketplaces), change is the hallmark of competition itself.52See Thomas M. Jorde & David J. Teece, Antitrust Policy and Innovation: Taking Account of Performance Competition and Competitor Cooperation, 147 J. Inst’l & Theoretical Econ. 118, 122 (1991) (“At minimum, we would propose that when the promotion of static consumer welfare and innovation are in conflict, the courts and administrative agencies should favor innovation. Adopting dynamic competition and innovation as the goal of antitrust would, in our view, serve consumer welfare over time more assuredly than would the current focus on short-run consumer welfare.”).

The following Sections illustrate these two tendencies. Section A discusses Antitrust Dystopia. Section B focuses on Antitrust Nostalgia. Both Sections draw from evidence within scholarship that calls for heightened antitrust enforcement in the digital sphere, particularly against firms that have access to large datasets of personal information concerning their users. We show that dystopia and nostalgia biases cause proponents to resort to precautionary reasoning; however, there is currently no evidence to warrant this precautionary approach. Indeed, while there is undoubtedly some level of uncertainty at play in digital markets, there is no evidence to suggest that the uncertainty could give rise to the type of fat-tailed situations where precautionary reasoning is arguably appropriate.

A. Dystopia

Recent antitrust scholarship and commentary has routinely voiced dystopian concerns, leading to several recurring tropes. One such trope is the oft-repeated mantra that the digital future will be bleak if governments do not act now. Similarly, it is often said that the emergence of large digital platforms poses threats to democracy that must, at least in part, be addressed through government intervention. Finally, critics often claim that the consolidation of digital markets will significantly slow innovation. Undergirding all of these is the claimed condition of fundamental uncertainty: reasoning from past experience is unavailing because this time will be different.

1. This Time is Different

As both the dystopia and nostalgia tendencies show, antitrust scholarship relating to digital competition often seems fearful of change. Scholars readily assume that new business realities complicate the task of antitrust authorities. Novel market features are often seen as a threat rather than an opportunity for authorities, consumers, and innovative rivals. The report on digital competition ordered by the European Commission neatly illustrates this view:

Despite the many benefits that digital innovation has brought, much of the enthusiasm and idealism that were so characteristic of the early years of the Internet has given way to concerns and scepticism.53Jacques Crémer, Yves-Alexandre De Montjoye & Heike Schweitzer, Competition Policy For The Digital Era 12 (2019) (emphasis added).

. . . .

Digitisation is profoundly changing our economies, societies, access to information, and ways of life. It has brought welcome innovation, new products and new services, and has become an integral part of our daily lives. However, there is increasing anxiety about its ubiquity, political and societal impact and, more relevant to our focus, about the concentration of power by a few very large digital firms.54Id. at 125 (emphasis added).

From a more technical and economic standpoint, commentators routinely conclude that digital markets display several features that arguably increase the likelihood of anticompetitive outcomes. They often ignore or minimize how these same features also benefit consumers, however, instead asserting that this time negative effects will predominate.

In a European Union committee report tasked with analyzing the competitive functioning of the digital economy, several prominent scholars concluded that:

The cost of production of digital services is much less than proportional to the number of customers served. While this aspect is not novel as such (bigger factories or retailers are often more efficient than smaller ones), the digital world pushes it to the extreme and this can result in a significant competitive advantage for incumbents.55Id. at 2 (emphasis added).

The economic phenomenon just described is commonly referred to as “increasing returns to scale.”56See, e.g., Hal R. Varian, Microeconomic Analysis 16 (3d ed. 1992) (“[W]hen output increases by more than the scale of the inputs, we say the technology exhibits increasing returns to scale.”). The European Commission’s report on digital competition further noted the following about these increasing returns:

[T]he specificities of many digital markets have arguably changed the balance of error cost and implementation costs, such that some modifications of the established tests, including the allocation of the burden of proof and the definition of the standard of proof, may be called for. In particular, in the context of highly concentrated markets characterised by strong network effects and subsequently high barriers to entry (a setting where impediments to entry which will not be easily corrected by markets), one may want to err on the side of disallowing types of conduct that are potentially anticompetitive, and to impose the burden of proof for showing pro-competitiveness on the incumbent. This may be even more true where platforms display a tendency to expand their dominant positions in ever more neighbouring markets, growing into digital ecosystems which become ever more difficult for users to leave. In such cases, there may, for example, be a presumption in favour of a duty to ensure interoperability.57Crémer et al., supra note 53, at 51 (emphasis added).

And Margrethe Vestager, the current head of DG Competition (the European Union’s main antitrust authority), made similar claims in a recent speech:

It’s not just that digitisation has made economies of scale more important than before. It’s also that the huge amount of data that some platforms have, and the huge networks behind them, can give them an edge that smaller rivals can’t match.58Margrethe Vestager, European Comm’n, Speech on Competition and the Digital Economy at OECD/G7 Conference in Paris (June 3, 2019) (emphasis added).

But while these increasing returns can cause markets to become more concentrated, they also imply that it is often more efficient to have a single firm serve the entire market.59See, e.g., W. Brian Arthur, Increasing Returns and the New World of Business, 74 Harv. Bus. Rev. 100, 106 (1996) (“In Marshall’s world, antitrust regulation is well understood. Allowing a single player to control, say, more than 35% of the silver market is tantamount to allowing monopoly pricing, and the government rightly steps in. In the increasing-returns world, things are more complicated. There are arguments in favor of allowing a product or company in the web of technology to dominate a market, as well as arguments against.”). For instance, to a first approximation, network effects, which are one potential source of increasing returns, imply that it is more valuable—not just to the platform, but to the users themselves—for all users to be present on the same network or platform.60Id. In other words, fragmentation—de-concentration—may be more of a problem than monopoly in markets that exhibit network effects and increasing returns to scale.61See Volker Nocke, Martin Peitz & Konrad Stahl, Platform Ownership, 5 J. Eur. Econ. Ass’n 1130, 1133 (2007). Given this, it is far from clear that antitrust authorities should try to prevent consolidation in markets that exhibit such characteristics, nor is it self-evident that these markets somehow produce less consumer surplus than markets that do not exhibit such increasing returns.62Whether or not they feature increasing returns to scale, recent research suggests that digital markets produce significant value for consumers. See, e.g., Erik Brynjolfsson, Avinash Collis & Felix Eggers, Using Massive Online Choice Experiments to Measure Changes in Well-Being, 116 Proc. Nat’l Acad. Scis. 7250, 7250 (2019) (“Our overall analyses reveal that digital goods have created large gains in well-being that are not reflected in conventional measures of GDP and productivity.”). Unfortunately, however, would-be antitrust reformers routinely overlook these important counterarguments or assume that they are meritless.

The idea that “this time is different” has also led scholars to argue that some industries deserve special protection against competitive disruption. A report published by the University of Chicago’s Stigler Center, for instance, argues that:

Digital Platforms are devastating the newspaper industry: Newspapers are a collateral damage of the digital platform revolution. Craigslist destroyed the lucrative newspaper classified ads, and Google and Facebook dramatically reduced the revenues newspapers could get from traditional advertising. Local newspapers have been hit particularly hard: At least 1800 newspapers closed in the United States since 2004, leaving more than 50% of US counties without a daily local paper. Every technological revolution destroys pre-existing business models. Creative destruction is the essence of a vibrant economy. In this respect, there is nothing new and nothing worrisome about this process. Yet, a vibrant, free, and plural media industry is necessary for a true democracy. The newspapers of yesteryear played an essential function in a democratic system.63Luigi Zingales & Filippo Maria Lancieri, Policy Brief, in George J. Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms: Final Report 6, 10 (2019) [hereinafter Stigler Center Report, Policy Brief] (emphasis added).

In this case, it is not that the market dynamics that are presumed to play out differently, but that the consequences in this market or for this industry will be uniquely dire.

The upshot is that antitrust scholarship often emphasizes the unique risks that new market realities create for competition, while idealizing the extent to which previous market realities led to procompetitive outcomes. The critics who mobilize these sentiments generally call for the introduction of precautionary measures to keep anticompetitive concerns at bay. As argued below, however, there is little reason to believe that such measures are necessary, or that they would even be beneficial.

2. The Future is Bleak

Building on the “this time is different” sentiment is the first big dystopian trope: that our digital future will be miserable if governments do not act now. This is well illustrated by a quote from Tim Wu’s The Curse of Bigness, in which he discusses the rise of “big tech”:

We have managed to recreate both the economics and politics of a century ago—the first Gilded Age—and remain in grave danger of repeating more of the signature errors of the twentieth century. As that era has taught us, extreme economic concentration yields gross inequality and material suffering, feeding an appetite for nationalistic and extremist leadership. Yet, as if blind to the greatest lessons of the last century, we are going down the same path. If we learned one thing from the Gilded Age, it should have been this: The road to fascism and dictatorship is paved with failures of economic policy to serve the needs of the general public.64Wu, supra note 17, at 14 (emphasis added).

The Stigler Center Report offers another example. The report cautions governments against the severe economic and social consequences that digital industries will purportedly give rise to, offering its suggested brand of state intervention as a necessary corrective: “[T]his report is offered in the spirit of ensuring a future of continued technological and economic progress and social well-being as we move further forward into the Digital Age.”65Market Structure and Antitrust Subcommittee, Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, Report, in George J. Stigler Center for the Study of the Economy and the State, Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms: Final Report 23, 28 (2019) [hereinafter Stigler Center Report, Antitrust Subcommittee].

Along similar lines, some scholars have suggested the digital world is not living up to its full potential. This is perhaps best illustrated by a passage written by economist Jason Furman and his co-authors, in a report commissioned by the UK Treasury:

Digital technology is providing substantial benefits to consumers and the economy. But digital markets are still not living up to their potential. A set of powerful economic factors have acted both to limit competition in the market at any point in time and also to limit sequential competition for the market in which new companies would overthrow the currently dominant ones. This means that consumers are missing out on the full benefits and innovations competition can bring.66Digital Competition Expert Panel, Unlocking Digital Competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel 17 (2019) (emphasis added). Digital Competition Expert Panel Chair Jason Furman also chaired the Council of Economic Advisers under the Obama Administration.

The view that governments must act now was also echoed by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission:

Important for Governments to act now, responding to current problems and anticipating future issues

We are at a critical time in the development of digital platforms and their impact on society. Digital platforms have fundamentally changed the way we interact with news, with each other, and with governments and business. It is also clear that the markets in which digital platforms and news media businesses operate will continue to evolve. It is very important that governments recognise the role digital platforms perform in our individual and collective lives, be responsive to emerging issues, and be proactive in anticipating challenges and problems.67Australian Competition & Consumer Commission, Digital Platforms Inquiry: Final Report 27 (2019).

In short, there is a long strand of antitrust scholarship that concludes governments must act immediately in the digital sphere or face the prospect of severe economic and social consequences. But while it is manifestly true that the future brings new risks and uncertainties and that the present is far from perfect, these critics often ignore the flipside of the same coin: things could also be worse today and, more importantly, there is no guarantee that the contemplated government interventions will lead to welfare improvements going forward.68In doing so, these commentators thus fall prey to the “Nirvana fallacy.” See Harold Demsetz, Information and Efficiency: Another Viewpoint, 12 J.L. & Econ. 1 (1969) (“[T]hose who adopt the nirvana viewpoint seek to discover discrepancies between the ideal and the real and if discrepancies are found, they deduce that the real is inefficient.”).

3. Our Democracy Is at Stake

Tightly linked to these first two tropes is the oft-repeated claim that, if left unchecked, the rise of large digital platforms may threaten the very fabric of western democracies. For instance, Columbia Professor Tim Wu—and now member of President Biden’s National Economic Council—has argued that big tech firms currently exert too much control over our daily lives:

Big tech is ubiquitous, seems to know too much about us, and seems to have too much power over what we see, hear, do, and even feel. It has reignited debates over who really rules, when the decisions of just a few people have great influence over everyone. Their power feels like “a kingly prerogative, inconsistent with our form of government” in the words of Senator John Sherman, for whom the Sherman Act is named.69Wu, supra note 17, at 21 (emphasis added).

The Stigler Center Report reached a similar conclusion:

This concentration of economic, media, data, and political power is potentially dangerous for our democracies . . . . To make matters worse, as more of our lives move online, the more commanding these companies will become. We are currently placing the ability to shape our democracies into the hands of a couple of unaccountable individuals. It is clear that something has to be done.70Stigler Center Report, Policy Brief, supra note 63, at 11 (emphasis added).

The Stigler Center Report also claims that Google and Facebook are in a unique position to thwart the democratic forces:

Digital platforms are uniquely powerful political actors: Google and Facebook may be the most powerful political agents of our time. They congregate five key characteristics that normally enable the capture of politicians and that hinder effective democratic oversight[.]

. . . .

In sum, Google and Facebook have the power of ExxonMobil, the New York Times, JPMorgan Chase, the NRA, and Boeing combined. Furthermore, all this combined power rests in the hands of just three people.71Id. at 9–10 (emphasis added).

Finally, Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) Chair Lina Khan famously argued that the way Amazon operates its retail platform excludes rivals, thus increasing economic concentration and threatening media freedom:

The political risks associated with Amazon’s market dominance also implicate some of the major concerns that animate antitrust laws. For instance, the risk that Amazon may retaliate against books that it disfavors— either to impose greater pressure on publishers or for other political reasons— raises concerns about media freedom.72Lina M. Khan, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 Yale L.J. 710, 767 (2017).

Even specific elements of these platforms’ behaviors are sometimes said to imperil our polity: “Digital platform self-preferencing threatens the American Dream. When digital platforms pick the winners and losers of our economy, we lose the American promise of upward mobility based on merit.”73Competition in Digital Technology Markets: Examining Self-Preferencing by Digital Platforms, Hearing Before the S. Judiciary Comm. Subcomm. on Antitrust, Competition Pol’y and Consumer Rts., 116th Cong. (Mar. 10, 2020) (testimony of Sally Hubbard, Dir. of Enforcement Strategy, Open Mkts Inst.) (emphasis added).

To summarize, critics routinely conclude that the advent of “big tech” today jeopardizes individual freedoms because the high levels of economic concentration that these markets exhibit allegedly translates inexorably into greater political power.74See, e.g., Luigi Zingales, Towards a Political Theory of the Firm, 31 J. Econ. Persps. 113, 124 (2017) (“Thus, in a fragmented and competitive economy, firms find it difficult to exert this power. In contrast, firms that achieve some market power can lobby (in the broader sense of the term) in a way that ordinary market participants cannot. Their market power gives them a comparative advantage at the influence game: the greater their market power, the more effective they are at obtaining what they want from the political system. Moreover, the more effective they are at obtaining what they want from the political system, the greater their market power will be, because they can block competitors and entrench themselves.”). Contra Kevin B. Grier, Michael C. Munger & Brian E. Roberts, The Industrial Organization of Corporate Political Participation, 53 So. Econ. J. 727, 737 (1991) (“Our results indicate that both sides are right, over some range of concentration. The relation between political activity and concentration is a polynomial of degree 2, rising and then falling, achieving a peak at a four-firm concentration ratio slightly below 0.5.”); Geoffrey Manne & Alec Stapp, Does Political Power Follow Economic Power?, Truth on the Market (Dec. 30, 2019), https://perma.cc/74JY-KPHN (“If we look at the lobbying expenditures of the top 50 companies in the US by market capitalization, we see an extremely weak (at best) relationship between firm size and political power (as proxied by lobbying expenditures)[.]”). What these critics miss (aside from the tenuousness of the asserted causal relationship between economic concentration and political power) is that the type of heavy-handed intervention against big tech firms that many of these critics prescribe may pose equal if not greater threats to individual freedoms.75For instance, regulating speech on social media may ultimately lead to dangerous government censorship. See, e.g., Niam Yaraghi, Regulating Free Speech on Social Media Is Dangerous And Futile, Brookings Inst. (Sept. 21, 2018), https://perma.cc/3DWN-FFBC; see also Geoffrey A. Manne, Dirk Auer & Samuel Bowman, Why ASEAN Competition Laws Should Not Emulate European Competition Policy, Sing. Econ. Rev. (forthcoming 2021) (“Endorsing the European approach to antitrust, in a naïve attempt to bring high-profile cases against large internet platforms, would prioritize political expediency over the rule of law. It would open the floodgates of antitrust litigation and facilitate deleterious tendencies, such as non-economic decision-making, rent-seeking, regulatory capture, and politically motivated enforcement.”). In other words, even if protecting individuals from the influence of powerful entities was a valid goal of antitrust policy, it is not clear that increased government intervention would achieve this end rather than the opposite.

4. Innovation Will Dwindle

Another recurring theme in Antitrust Dystopia is the idea that big tech firms will cause innovation to slow down if governments do not intervene. The intuition is that, because of their powerful market positions, big tech firms can either capture the profits of their rivals (by using their bottleneck positions to squeeze them) or snuff out budding competitors through so-called killer acquisitions. This, in turn, is said to reduce both rivals’ and incumbents’ incentives to innovate: the former because their expected profits from innovation are reduced, and the latter because they no longer need to innovate in order to best their competition.

These fears are perhaps best encapsulated by economist Hal Singer’s comments during the 2019 FTC hearings, as well as the paper on which these claims are based76See Kevin Caves & Hal Singer, When the Econometrician Shrugged: Identifying and Plugging Gaps in the Consumer-Welfare Standard, 26 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 395, 416 (2018) (“[I]nnovation harms could be addressed outside antitrust pursuant to a nondiscrimination standard . . . . Like a rule-of-reason case under antitrust, the complainant would bear the burden to show that the differential treatment violated the nondiscrimination standard, assuming it could meet certain evidentiary criteria.”).:

Dominant tech platforms can also exploit the vast amounts of user data made available only to them by monitoring what their users do both on and off their platforms and then appropriating the best performing ideas, functionality, and nonpatentable products pioneered by independent providers. If these practices are left unchecked, the resulting competitive landscape could become so inhospitable that independents might throw in the towel, leading to less innovation at the platform’s edges.77Competition and Consumer Protection in the 21st Century, FTC Hearing #3 Day 3: Multi-Sided Platforms, Labor Markets, and Potential Competition Before the FTC (2018) (statement of Hal Singer, Managing Dir., Econ One) (emphasis added).

On a more dramatic note, in a piece promoting the Stigler Center Report, Professor Luigi Zingales referred to big tech firms as “robber barons” that levy a tax on innovation:

[B]y positioning themselves as a mandatory bottleneck between new entrants and customers, digital platforms play the role of the traditional robber barons, who exploited their position of gatekeepers to extract a fee from all travelers. Not only does this fee represent a tax on innovation, it also reduces the value new entrants can fetch alone and thus the price at which they would be acquired.78Luigi Zingales, “The Digital Robber Barons Kill Innovation”: The Stigler Center’s Report Enters the Senate, ProMarket (Sept. 25, 2019), https://perma.cc/KHF4-8KVU (emphasis added).

Merger enforcement in particular has become a key area of focus for these critics, who accuse large firms of buying startups to kill off future competition.79See, e.g., Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer & Song Ma, Killer Acquisitions, 129 J. Pol. Econ. 649, 649 (2021) (“This paper argues incumbent firms may acquire innovative targets solely to discontinue the target’s innovation projects and preempt future competition.”). With this in mind, some scholars have called on authorities to implement far-reaching measures that would allegedly protect innovation from the depredations of “big tech.” For instance, a report ordered by the European Commission concluded that digital mergers should be much more heavily scrutinized:

Where network effects and strong economies of scale and scope lead to a growing degree of concentration, competition law must be careful to ensure that strong and entrenched positions remain exposed to competitive challenges. The test proposed here would imply a heightened degree of control of acquisitions of small start-ups by dominant platforms and/or ecosystems, as they would be analysed as a possible defensive strategy against partial user defection from the ecosystem as a whole. Where an acquisition plausibly is part of such a strategy, the burden of proof is on the notifying parties to show that the adverse effects on competition are offset by merger-specific efficiencies.80Crémer et al., supra note 53, at 124 (emphasis added).

Along similar lines, the Stigler Center Report cautions that so-called “kill zone” mergers may entrench dominant incumbents and harm innovation:

While investment in innovation will continue, the type of innovation that will be funded will be broadly determined by the incumbent and its strategies. Disruptive innovation in markets that are characterized by high concentration levels and network effects is likely to be reduced compared to a competitive market. One of the few sources of entry in digital platforms comes from rival platforms that enter each other’s markets, as these large firms are more able to overcome entry barriers of all kinds.81Stigler Center Report, Antitrust Subcommittee, supra note 65, at 76 (emphasis added).

To be clear, this Article’s claim is not that digital platforms can never slow down innovation. The effect that market concentration and firm size have on innovation is ambiguous in theory and a hotly contested empirical question.82For an overview of this question, see Dirk Auer, Structuralist Innovation: A Shaky Legal Presumption in Need of an Overhaul, CPI Antitrust Chron., Dec. 2018, https://perma.cc/8VY8-69TJ. See also Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright, Introduction, in Competition Policy and Patent Law Under Uncertainty: Regulating Innovation 1 (Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright eds., 2011) (“[T]he ratio of what is known to unknown with respect to the relationship between innovation, competition, and regulatory policy is staggeringly low. In addition to this uncertainty concerning the relationships between regulation, innovation, and economic growth, the process of innovation itself is not well understood.”); Richard J. Gilbert, Competition and Innovation, UC Berkeley Competition Pol’y Ctr. 8 (Jan. 17, 2007), https://perma.cc/HDX6-Q7JQ (“Economic theory supports neither the view that market power generally threatens innovation by lowering the return to innovative efforts nor the Schumpeterian view that concentrated markets generally promote innovation by providing a stable platform to fund R&D and by making it easier for the firm to capture its benefits.”). The above critics do not merely argue that large digital platforms sometimes slow down innovation, however. Instead, they posit that this effect is so systematic and severe that it is necessary to impose precautionary measures—for instance, shifting the burden of proof in merger cases—whatever the cost.

To make matters worse, the evidence these critics cite to support their claims is highly conjectural. Economists Kevin Caves and Hal Singer, for example, put forward only weak anecdotal evidence to support their call for tougher antitrust enforcement against digital platforms, as they even acknowledge: “The empirical evidence that edge innovation has been diminished by dominant tech platforms is partially anecdotal and not dispositive . . . .”83Caves & Singer, supra note 76, at 402.

Likewise, Professors Giulio Federico, Fiona Scott Morton and Carl Shapiro dismiss a large strand of economic literature concerning the link between competition and innovation by claiming that its authors did not specifically address the effect of mergers.84Giulio Federico, Fiona Scott Morton & Carl Shapiro, Antitrust and Innovation: Welcoming and Protecting Disruption, 20 Innovation Pol’y and the Econ. 125, 136 (2020) (“[T]he models used in this literature generally do not analyze the effects of mergers, but instead look at exogenous variations in the intensity of product market competition. The authors of the cited papers often do not assert that their analysis applies to the antitrust analysis of mergers.”). While this may be a useful caveat, it does nothing to support their own view that increased product market competition systematically boosts innovation. Indeed, the approach taken by Giulio Federico and his coauthors (like most of the relevant economic literature) is myopically committed to a model of innovation that ties innovation to market structure, and (unlike the literature it criticizes) even assumes that the relationship is unidirectional: changes in market structure affect incentives to innovate, but not the other way around. But the reality is far more complicated:

To summarize, the basic framework employed in discussions about innovation, technology policy, and competition policy is often remarkably naïve, highly incomplete, and burdened by a myopic focus on market structure as the key determinant of innovation. Indeed, it is common to find a debate about innovation policy among economists collapsing into a rather narrow discussion of the relative virtues of competition and monopoly, as if they were the main determinants of innovation. Clearly, much more is at work.85J. Gregory Sidak & David J. Teece, Dynamic Competition in Antitrust Law, 5 J. Competition L. & Econ. 581, 589 (2009).

Again, our argument is not that these authors’ claims about competition and innovation are necessarily wrong—only that they put forward little to no theoretical or empirical evidence to support their dire claims of curtailed innovation absent far-reaching precautionary measures.

B. Nostalgia

The antitrust literature surrounding digital competition is also beset by a strong and often-problematic sense of nostalgia. Scholars (and certain aspects of antitrust doctrine) are skeptical or fearful of change, even though change is a hallmark of digital industries where disruption has been the norm for decades.86See, e.g., Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail xvi (1997). This nostalgia can take several forms.

For a start, although it has no direct bearing on the development or interpretation of the law itself, nostalgic antitrust scholars have devoted extraordinary attention to dissecting and reinterpreting the historical origins of early US antitrust legislation (largely the Sherman Act). This sort of “meta-nostalgia” is consistent with a resurgent effort on the part of some activists and scholars to reinvigorate the populist sentiments of the late nineteenth century and progressive sentiments of the early twentieth century more broadly—including what some hold to be the apotheosis of those movements: the 1890 Sherman Act and the 1914 Clayton and FTC Acts. Although borne out of this broader political movement, such writing is more pointedly employed in an attempt to discredit subsequent judicial interpretations of antitrust law and the general common-law-like approach to antitrust jurisprudence.

Bearing more directly on the antitrust enterprise, nostalgic scholars tend to assume that markets were less problematic in the past, and that new business realities fundamentally alter the optimal balance of antitrust enforcement. This is nothing new, for as early as 1942 Joseph Schumpeter spoke dismissively of scholars advocating a view that “involves the creation of an entirely imaginary golden age of perfect competition that at some time somehow metamorphosed itself into the monopolistic age[.]”87Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy 81 (1942).

But the problem is exacerbated in digital markets where change often takes the form of technological or business process innovation, both of which policy should generally encourage. “The critical point here is that innovation is closely related to antitrust error. The argument is simple. Because innovation involves new products and business practices, courts and economists’ initial understanding of these practices will skew initial likelihoods that innovation is anticompetitive and the proper subject of antitrust scrutiny.”88See Geoffrey A. Manne & Joshua D. Wright, Innovation and The Limits of Antitrust, 6 J. Competition L. & Econ. 153, 167 (2010). We simply do not know enough—especially about the relationship between firm structure, market structure, and innovation—to view change with the skepticism that some scholars do.89See, e.g., Caves & Singer, supra note 76.

Nevertheless, a host of scholars, regulators, politicians, and, of course, competitors tend to confront novel business structures and practices as if they undermine presumptively efficient markets, thus counseling enforcement to thwart these practices—precisely the tendency to condemn “ununderstandable practices” decried by Ronald Coase.90Coase, supra note 33, at 67.

Many further argue in favor of more aggressive interventions in digital markets in order to “restore” markets to the presumptively preferable state that existed before allegedly anticompetitive conduct occurred. In the past, antitrust enforcers mostly relied on cease-and-desist orders and deterrent sanctions (such as fines, treble damages for victims, and criminal prosecution) to police anticompetitive conduct.91See, e.g., A. Douglas Melamed, Afterword: The Purposes of Antitrust Remedies, 76 Antitrust L.J. 359, 364 (2009) (drawing a typology of antitrust remedies and suggesting that restorative remedies lie at the outer bounds of antitrust enforcement, or at the very least that authorities should impose such remedies with great caution). Such sanctions are mostly forward-looking (with the partial exception of damages awarded to victims of anticompetitive conduct). Authorities intended only to prevent anticompetitive harm from occurring in the future, whether by putting an end to a given practice or by deterring other firms from adopting a similar course of conduct. Today, however, many scholars consider these intervention methods to be insufficient in the realm of digital competition. They urge antitrust authorities to go one step further and impose remedies that “restore” markets to the presumptively efficient state that existed before the challenged conduct occurred. The underlying assumption is that the state of competition before an infringement took place is necessarily better than that which exists in the aftermath of a firm’s conduct, and that the differences that exist between both states are caused by this conduct.

These nostalgic inclinations are based on premises that are far from self-evident, however. In fact, as explained below, the error-cost framework that heavily influenced antitrust enforcement in the US (and to a lesser extent in the EU) is designed, among other things, to avoid the social costs that might stem from overly “nostalgic” enforcement. This makes it particularly ironic that nostalgic advocates for more aggressive intervention base their arguments in large measure on a rejection of the error-cost framework.

1. Progressive and Populist Nostalgia Aimed at Furthering a Broader “Democratization” Movement

The current resurgence of activist antitrust—variously labeled “populist antitrust,” “neo-Brandeisian antitrust,” or “hipster antitrust”—rests in considerable part (as its monikers suggest) on a deeply nostalgic sentiment. The hearkening back to activists’ preferred political and legal historical eras is part of a broader movement in both the academy92See Jedediah Britton-Purdy, David Singh Grewal, Amy Kapczynski & K. Sabeel Rahman, Building a Law-and-Political-Economy Framework: Beyond the Twentieth-Century Synthesis, 129 Yale L.J. 1784, 1826 (2020) (“Finally, regrounding law and policy analysis in a broad conception of equality will require scholars to articulate substantive notions of what a commitment to equality should mean in different domains of law . . . . This means reengaging with lines of argument . . . [aimed at destabilizing] welfarism and its questionable metaethical underpinnings . . . from liberal theorists concerned with the autonomy-degrading aspects of welfarism to Marxian-inspired accounts of need.”). and in political discourse93See, e.g., Gerald Berk, Monopoly and Its Discontents, Am. Prospect (Oct. 9, 2019), https://perma.cc/B8FE-E4F4 (“Democrats of all stripes speak the language of anti-monopoly now, whether they acknowledge it or not. Some, like Warren, speak it in a pure form. Others combine anti-monopoly inquiry with rival forms of analysis, which look incompatible at first glance. Sanders’s plan for rural America combines anti-monopoly and class analysis to explain how corporate monopolies turned independent farmers into an impoverished proletariat through an oppressive subcontracting system. His solution is antitrust and price supports, not public ownership. Neoliberal corporatists Hillary Clinton, Mark Warner, and Amy Klobuchar, who once saw government regulation as the primary obstacle to technological innovation and entrepreneurship, now place tech monopolies atop their list.”). to (re-)build a “more genuine democracy that also takes seriously questions of economic power and racial subordination; . . . the displacement of concentrated corporate power and rooting of new forms of worker power; [and] . . . the challenges posed by emerging forms of power and control arising from new technologies . . . .”94Britton-Purdy et al., supra note 92, at 1834–35. “This [antitrust] moment is part of a larger one in which settled orthodoxies in many other areas of law and policy, particularly those that shape economic life, have been ruptured and new constructive projects have begun.”95Sanjukta Paul, Reconsidering Judicial Supremacy in Antitrust, 131 Yale L.J. (forthcoming) (manuscript at 2). “A necessary, though not sufficient, condition of [democratizing the economy] is to right the balance of law-making power, in antitrust law, in favor of the democratic branches of government.”96Id. at 56.

The antitrust prong of this “democratization” movement is focused on reviving what proponents see as the “true” antitrust tradition, which was illegitimately subverted by the neoliberalism of the late twentieth century. “Antitrust laws historically sought to protect consumers and small suppliers from noncompetitive pricing, preserve open markets to all comers, and disperse economic and political power. The Reagan administration—with no input from Congress—rewrote antitrust to focus on the concept of neoclassical economic efficiency.”97Lina Khan & Sandeep Vaheesan, Market Power and Inequality: The Antitrust Counterrevolution and Its Discontents, 11 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 235, 236 (2017).

A significant part of this effort is a continual hearkening back to the origins of early US antitrust legislation, particularly the legislative history surrounding the enactment of the Sherman Act.98See, e.g., Peter C. Carstensen, Antitrust Law and the Paradigm of Industrial Organization, 16 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 487, 488 (1983); John J. Flynn, The Reagan Administration’s Antitrust Policy, “Original Intent” and the Legislative History of the Sherman Act, 33 Antitrust Bull. 259, 263–64 (1988); Robert H. Lande, Wealth Transfers as the Original and Primary Concern of Antitrust: The Efficiency Interpretation Challenged, 34 Hastings L.J. 65, 82–83 (1982); Paul, supra note 95, at 27–39; see generally David Millon, The Sherman Act and the Balance of Power, 61 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1219 (1988). Recent scholarship has sought to justify what amounts to a sea change in antitrust law by suggesting that such a shift would merely reinstate the original intent behind federal antitrust legislation. In particular, this approach would supplant, and rescind, the judicially directed contours of antitrust law over the past 100 years with a “claimed” more fulsome and direct congressional mandate:

The legislative record shows that Congress . . . . made the affirmative purpose of the legislation quite clear. That purpose was to respond to the recent rise of concentrated corporate power by means of an overall decision rule that would disperse economic coordination rights rather than further concentrate them. Thus, Congress already set specific normative criteria for allocating economic coordination rights under the Sherman Act; it did not leave it to the courts to do so.99Paul, supra note 95, at 4. See also Sandeep Vaheesan, The Evolving Populisms of Antitrust, 93 Neb. L. Rev. 370, 374 (2014) (“[C]onsumer protection would be true to the legislative intent of Congress in enacting the antitrust laws—preventing unjustified wealth transfers from consumers to producers.”).

Interestingly, a significant number of scholars who advocate substantial precautionary antitrust reform are nevertheless deeply critical of these nostalgia-infused arguments. Professor Herbert Hovenkamp, for example, offers a strong critique of progressive antitrust, concluding that:

Not only have progressives been expansionist in antitrust policy, they also pursued policies that did not fit well into any coherent vision of the economy, often in ways that hindered rather than furthered competitiveness and economic growth—all while injuring the very interest groups the policies were designed to protect.

. . . .

[A]lthough the progressive state’s expanded ideas about the role of regulation may be justified, these views should not spill into antitrust policy. Rather, the country is best served by a more-or-less neoclassical antitrust policy with consumer welfare, or output maximization, as its guiding principle. Not only is such a policy consistent with overall economic growth, it is also more likely to provide resistance against special-interest capture, which is a particular vulnerability of the progressive state.100Herbert Hovenkamp, Progressive Antitrust, 2018 U. Ill. L. Rev. 71, 76.

Indeed, although these progressive movement activists are surely the most nostalgic of all, their revivalist approach does not factor in any significant way into the central discussion of this Article. While some of these writers do also engage with the substantive debate over the proper antitrust treatment of data and digital platforms (and thus some of this work is discussed below), the effort to justify their preferred outcomes with an originalist appeal to nineteenth century legislative intent is simply irrelevant to the contemporary discussion. The broader political movement of which it is a part may be worth taking seriously, but as a matter of political science, not of antitrust law and economics. It is worth mentioning, but not worthy of further consideration here.

2. Much Antitrust Doctrine is Inherently Backward-Looking

The application of longstanding antitrust doctrine to digital platform technologies is often difficult:

[C]ompetition law instruments, such as market shares or concentration ratios, used for traditional markets in order to assess dominance cannot be easily used when it comes to platforms because of the multiplicity of services they offer simultaneously to different groups of consumers. It also means that market power indicators based on a comparison of price and cost . . . cannot be used on each side of the platform to assess its market power. It finally means that the characterization of an abusive practice of a platform may be either different or more complex than in the case of traditional markets.101Frederic Jenny, Competition Law and Digital Ecosystems: Learning to Walk Before We Run 4 (Jan. 20, 2021) (unpublished manuscript), https://perma.cc/SKY4-26W4.

But the disconnect is made even more stark because much antitrust doctrine is inherently backward-looking. Antitrust Nostalgia is not simply a function of overly precautionary scholars advocating against change; it is also embedded within much antitrust process and doctrine.