Abstract. We are in an age of massive multidistrict litigation (“MDLs”). MDLs contain thousands, sometimes tens-of-thousands of individual cases, involving the laws of all states and territories, and are handled by a single judge. Around half of all federal court cases are consolidated within an MDL. These MDL-assigned judges necessarily have the power to create new rules of law and practice through the sheer number of decisions and opinions required to handle pretrial matters. These judges are also adopting ad hoc practices like “direct filing” to ease their administrative burdens in the initiation of cases within a single MDL.

The combination of these two things (the number of decisions required in MDLs and the adoption of direct filing) has led to a new phenomenon: judicial disregard for the “home court” designation of direct-file plaintiffs.

Over the past several years, dozens of decisions parroting language from a handful of decisions, which were written primarily by one or two judges, have created a new rule of jurisdiction: Although plaintiffs who do not directly file in MDLs can file in any appropriate court, await transfer to the MDL court for all pretrial matters, and be remanded back to their original chosen jurisdiction for trial, a direct-file plaintiff will only be remanded “back” to the state where the injury was sustained (typically defined as the place of implantation in the massive medical products MDLs). This rule applies regardless of whether the plaintiffs utilizing direct filing would have filed in that state of implantation originally but for the administrative convenience of direct filing. This is a new trend in MDLs that turns a “convenient” administrative short-cut into a practice that overrides a plaintiff’s choice of forum, potentially impacting substantive outcomes.

Attorneys that file in MDLs and desire to protect their home court of choice should forego direct filing and instead file in their chosen court, then move or wait for transfer into the MDL.

Introduction

Plaintiffs in tort cases typically have several choices to make in filing their suit: where to file, what claims to include, and what kind of damages to seek. In the product liability matters typically consolidated in a multidistrict litigation (“MDL”), federal rules allow a plaintiff to file in any of several potential venues.128 U.S.C. § 1391(b). While the parties, once engaged in the lawsuit, may argue about which state law should apply to the claims, it is the home state where the matter is filed that determines the choice-of-law rules to balance the competing interests and decide which interested state’s law to then apply.2See Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Elec. Mfg. Co., 313 U.S. 487, 496 (1941). Choice-of-law rules vary from state to state, so the ultimate rule of law to be applied in a case that is, say, filed in Texas and involves a Texas plaintiff injured by a product implanted in Oklahoma and manufactured in California by a company with a corporate home in Delaware, is not a foregone conclusion.3See Larry Kramer, Choice of Law in Complex Litigation, 71 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 547, 579 n.126 (1996). The only foregone conclusion is that the Texas court where the plaintiff chose to file her suit will use Texas choice-of-law rules to make that decision.4See Klaxon, 313 U.S. at 496 (holding that a federal court sitting in diversity applies the choice-of-law principles of the forum state to decide which state’s substantive law controls).

Or, rather, this was the foregone conclusion. Now there is a new and small, but steadily growing, group of cases that permits a judge to override or ignore a plaintiff’s choice of original filing jurisdiction and instead declare that the place of implantation determines the court that sets the choice-of-law rules for the dispute. In the above example, this would change the Texas-law-based claim into an Oklahoma-law-based claim.

This group of cases arises out of product liability MDLs, the massive, consolidated cases that make up around half of the entire federal caseload.5MDL Cases Continue to Dominate the Federal Caseload, Rules4MDLs (Mar. 19, 2020), https://perma.cc/B4JJ-QC9V (“[T]he concentration of federal civil cases in multidistrict litigation (MDLs) continues a five-year trend, hovering at nearly half of the total federal civil caseload when adjusted for social security and non-death penalty prisoner cases.”).. Following the growth of MDLs involving products—typically medical or consumer products—judges began to allow for “direct filing.” This is the practice of permitting plaintiffs to skip the step of filing in their chosen venue—which results in the case being transferred to the MDL court and consolidated with the MDL docket—and, instead, file directly in the MDL court, getting automatically added to the ongoing MDL itself. This is an ad hoc procedure that occurs outside of any rules of civil procedure but is frequently characterized as an administrative convenience.6See Andrew D. Bradt, The Shortest Distance: Direct Filing and Choice of Law in Multidistrict Litigation, 88 Notre Dame L. Rev. 759, 795–96 (2012); see also In re Heartland Payment Sys., Inc. Customer Data Sec. Breach Litig., No. 4:09-md-02046, 2011 WL 1232352, at *4 (S.D. Tex. Mar. 31, 2011) (quoting In re Vioxx Prods. Liab. Litig., 478 F. Supp. 2d 897, 904 (E.D. La. 2007)) (discussing benefits and drawbacks of direct filing).

In 2012, Professor Andrew Bradt identified problems arising out of this procedure, as it was then used, in his article, The Shortest Distance: Direct Filing and Choice of Law in Multidistrict Litigation.7Bradt, supra note 6, at 763–64. Bradt highlighted the problems that arise when matters from all over the country are directly filed into MDLs, which leaves choice-of-law issues in disarray.8See id. at 763–64. There is no obvious “home court” to send the directly filed cases “back” to once MDL proceedings are complete, and there is no obvious “home-state” law to apply to any individual legal issues.9See id. Bradt posited that the issue could be resolved by having direct-file plaintiffs designate a proper home venue.10Id. at 765. This would allow our Texan plaintiff in the above example to designate Texas as the court she would have filed in, but for the expedience of direct filing. Our Texan plaintiff does not intend to change her Texas case—and Texas counsel—in any way by directly filing in an MDL, and she states this plainly by designating the appropriate Texas district court as her proper home venue on the short form complaint. This solution appeared to preserve the efficiency benefits of direct filing while eliminating the choice-of-law confusion from the same system.

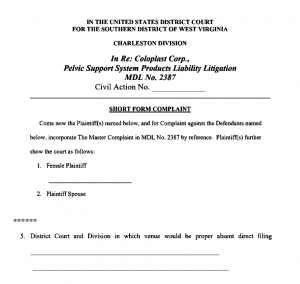

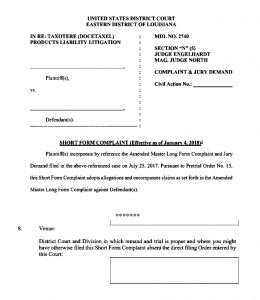

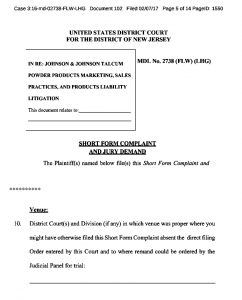

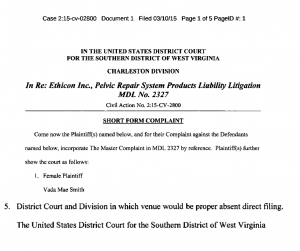

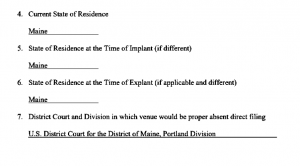

This was a simple and plausible solution to the problem created by direct filing. And since the publication of Bradt’s article, many MDLs have added a designation like that in their direct-file short forms.11See infra Part III. A new problem arises, however, from how MDL judges actually apply Bradt’s resolution. MDL decisions since the Bradt article demonstrate that, overwhelmingly, MDL judges ignore the proper home venue designation and simply declare the place of injury (substituting the place of implantation as the shorthand for the place of injury) as the “home” of the case, thus setting the choice-of-law rules.12See infra Part V. This practice disregards the plaintiff’s choice allowed by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which permit the filing of cases in any number of possible jurisdictions.

Consider a hypothetical MDL involving a New Jersey manufacturer of a medical product, which is sent to a district court in Ohio for all pretrial proceedings. Two Louisiana plaintiffs injured by the medical product want to file cases in the MDL. Plaintiff One opts for direct filing in the Ohio court, and designates New Jersey as the home jurisdiction, due to the defendants’ design, marketing, and manufacture of the product in New Jersey. Plaintiff Two opts to file in the District of New Jersey for the same reasons and then waits for her matter to be transferred to the Ohio court. The Ohio judge handles all pretrial matters within the MDL and ultimately remands all cases back to their home courts. Under this developing direct-filing “rule,” Plaintiff One will find herself in a Louisiana federal court, unlike Plaintiff Two, who will be duly remanded back to New Jersey. Although both Louisiana and New Jersey courts will possibly need to conduct a choice-of-law analysis, the starting point of that analysis is the conflict-of-law rules applied by the state in which the court sits. Plaintiff One ends up with a Louisiana-law-based choice-of-law analysis, while Plaintiff Two gets a New Jersey-law-based choice-of-law analysis. Direct filing, as an administrative shortcut, should not have this potentially substantive effect. To the extent that it does, parties and attorneys should be aware of this possibility and weigh the potential risks posed by direct filing. Additional risks involve whether counsel is even licensed to practice in the “surprise” remand jurisdiction.

Since the publication of Bradt’s article in 2012, the number of filed requests for consolidation before the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (“JPML”), and granted MDLs from the JPML, has remained largely constant.13See MDL Cases Continue to Dominate the Federal Caseload, supra note 5. In every year between 2012 and now, there have been around sixty to seventy pending separate product liability-based MDLs,14E.g., U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Calendar Year Statistics: January through December 2020, at 8 (2021), https://perma.cc/Q2TQ-5RS8 (noting that there were 61 pending products liability MDLs in 2020); U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Calendar Year Statistics of the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation: January through December 2012, at 12 (2013), https://perma.cc/JRB4-HEZW (noting that there were 72 pending products liability MDLs in 2012). and many of the judges overseeing these actions have opted for direct filing.15See U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Multidistrict Litigation Terminated Through September 30, 2020, at 2 (2020),https://perma.cc/Y6NW-2NW8. In a statistical analysis produced by the JPML, it was reported that 119,529 matters have been filed with the JPML and transferred pursuant to its rules, while slightly more—138,722 matters—have been directly filed into various MDLs since the practice started in 1968 through 2020. Id. Many judges permitting direct filing further allow individual plaintiffs to join the MDL by filing simple form petitions, in which a few questions establishing the plaintiff’s identity, product use, and injury are completed in a combination of check boxes and fill-in-the-blank questions.16See infra Part III. Also, since Bradt’s paper, many of these form petitions include a required home-state-forum designation, in which the plaintiff states the court that she would have filed her suit in, had direct filing into the MDL court not been an option.17See infra Figure 3.

This paper reviews published and unpublished opinions generated by MDL judges, as well as judges to whom individual suits have been remanded, in large product liability matters, handled since Bradt’s 2012 paper, to determine whether judges are honoring the plaintiffs’ choice of designated home court or ignoring the choices in favor of their own expectations about the proper applicable law. This review demonstrates that the overwhelming majority of these decisions ignore the home-state-forum designation and simply declare that the proper remand destination is the court where the implantation or exposure or contact with the challenged product occurred. The pace of these decisions has increased dramatically in the past year, due in part to both MDL-handling judges and remand-court judges applying identical, tersely drafted language from a handful of medical product liability cases.18See infra Part V.

This is a troubling development as the number of cited and citable cases that invalidate plaintiffs’ choice of home court forum grows. Bradt succeeded in one way, in that his proposal has been widely adopted in direct-filing cases and now short form complaints requiring the designation of a home state or “where you would have filed” question are practically industry standard.19See, e.g., McNew v. C.R. Bard, Inc., No. 19-CV-195, 2020 WL 759299, at *1 (N.D. Tex. Feb. 14, 2020) (“The short-form complaint included a field where plaintiffs could identify the district and division where venue would have been proper absent the MDL.”). But his “solution” to the choice-of-law problem has been rendered meaningless now that so many judges require that designation by a plaintiff, then ignore that designation and instead insist on looking to the place of injury, further defined as “place of implantation” or exposure or ingestion.20See infra Part V. Judges should not be faulted in making this declaration, as there are so many written (if unpublished) opinions declaring this to be the rule and no strong body of contrary case law suggesting that the plaintiff’s selection should control.21Id. But this newly developed body of law conflates the plaintiffs’ choice of home forum and the ultimate state law to be applied by skipping steps—steps that could impact what state applies to substantive issues. As another example, we return to Plaintiff One, from Louisiana, from the above hypothetical. Plaintiff One selects New Jersey, the home state of a major defendant, as the “place I would have filed but for direct filing” on her form. The MDL judge notes that Plaintiff One lives in and was injured in Louisiana, not New Jersey, and so instead applies Louisiana’s rule on statute of limitations when considering a motion to dismiss. However, if Plaintiff One had simply filed her suit in New Jersey, New Jersey’s choice-of-law rules would have applied to determine which state’s statute of limitations should apply to her claim. In fact, Plaintiff One designated New Jersey as her home state on her short form precisely because of New Jersey’s two-year limitations rule, anticipating that New Jersey law would arguably apply to limit the negligent acts of a New Jersey company. But she now is forced to argue why Louisiana’s choice-of-law rules should allow for the application of New Jersey’s statute of limitations in her case.

Part I of this paper provides an explanation of MDL practices and procedures, including how and why direct filings and short form complaints exist. Part II then looks at the historic cases exploring the conflict between a centralized MDL court and an individual plaintiff’s choice-of-law issues. Part III will address Bradt’s proposal and how it has been adopted and used by product liability MDL judges. Parts IV and V will then review the rulings on plaintiffs’ home-state selections in rulings from MDL judges and remand judges that implicate—or ignore—the plaintiffs’ home-state choice; Part IV will look at those decisions that refer to and apply the plaintiff’s designated choice and Part V will review those that disregard the stated choice or ignore it altogether in order to apply this new rule. Part VI concludes with an argument as to why the cases in Part V constitute a dangerous precedent that is building into a new rule under common law, such that attorneys evaluating where to file possible MDL cases should understand the risks to their clients. Part VI also concludes with new solutions that will either recognize the new rule expressly, so as to avoid setting traps for unwary plaintiffs and counsel, or, preferably, disregard this rule and instead ensure that plaintiffs’ home-state designations are indeed used as the starting point for all ensuing choice-of-law conflicts.

I. MDL and the Advent of Direct Filing

Federal MDL cases dominate the national federal civil litigation docket.22According to a statistical report released by the JPML, “[d]uring the twelve-month period ending September 30, 2019, 49,042 civil actions” were filed directly in or transferred into active MDLs. U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Statistical Analysis of Multidistrict Litigation Under 28 U.S.C. § 1407: Fiscal Year 2019, at 3 (2020), https://perma.cc/36N5-YKU3. While it is difficult to find statistics on the total federal cases filed within the same time period, there were 94,206 total civil suits filed under diversity jurisdiction in 2019 total. Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics 2019, U.S. Cts., https://perma.cc/GU3N-Z7KM. In 2019, cases filed into or transferred into an MDL accounted for forty-seven percent of pending civil cases, by one center’s analysis.23MDL Cases Continue to Dominate the Federal Caseload, supra note 5. Note that MDLs are distinct from class actions, which consolidate many cases into a single suit. An MDL is a consolidation, only for pretrial purposes, of many individual actions that nonetheless are filed individually and retain their individual character. Bradt,supra note 6, at 791–93 (“MDL’s primary difference from the class action is that the cases within it retain their individual identities. In other words, instead of the case being formally litigated by a representative on behalf of a group of absentee plaintiffs, the cases in an MDL keep their individual character . . . . [I]t is important to note the ways in which an MDL is different from a class action. Indeed, although MDL resembles in important ways a representative suit, it is not quite the same, because the cases retain their individual character. Unlike a class action, there are no absentee plaintiffs, and the cases are separately filed and prosecuted. And there will not be a single jury trial to decide the entirety of the case. As a result, the MDL has something of a hybrid character—not quite as aggregated as a class action, but consolidated to a significant degree.” (footnote omitted)). A large number of these MDLs involve product liability matters,24U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, Calendar Year Statistics: January Through December 2019 (2020), https://perma.cc/3FTC-P5EQ. and those product liability MDLs can involve thousands of individual cases asserting the same or similar claims against the same defendant.25For example, over 96,000 cases were filed into In re Roundup Products Liability Litigation, see Hannah Albarazi, Roundup MDL Judge Prods Monsanto to Settle Cases Earlier, Law360 (Aug. 18, 2021, 9:47 PM), https://perma.cc/TG6S-NVMJ, and over 250,000 were filed into the In re 3M Combat Arms Earplug Products Liability Litigation, see Carron Nicks, 3M Company’s Military Earplug Multi-District Litigation, Nat’l L. Rev. (Sept. 21, 2021), https://perma.cc/3HNM-SZWF.

For example, a new study is published that shows that a popular prescription medication has been linked to a deleterious side effect. Lawsuits begin to appear around the country, all of them raising similar product liability claims against the manufacturer. At some point, after some number of similar cases with similar claims have been filed, a plaintiff, defendant, or a group of either files for consolidation of these cases as an MDL by filing a short motion with the JPML. The motion will argue two things: (1) the group of matters should be consolidated, and (2) the consolidated matters should be handled by a specific judge or in a specific court.26See James M. Wood, The Judicial Coordination of Drug and Device Litigation: A Review and Critique, 54 Food & Drug L.J. 325, 332–35 (1999) (discussing common issues and locations in JPML filings). Location of the proposed MDL court is sometimes argued in motions, along with factors like access to airports and number of hotel rooms. See Andrew Barron, Abandoning Centrality: Multidistrict Litigation After COVID-19, Calif. L. Rev. Blog (Nov. 2020), https://perma.cc/UZJ4-GTV2. However, centrality of an MDL court (i.e., being in the geographic center of the country) seems to be diminishing in importance as a factor in selecting MDL courts. Id.

MDL is governed by a single federal statute, which establishes the JPML.2728 U.S.C. § 1407. The JPML is authorized by 28 U.S.C. section 1407, which creates the panel and authorizes it to review cases for potential consolidation.28Id. The JPML consists of a group of district court judges from across all districts that meets quarterly and determines whether to grant requests for consolidation. The JPML can consolidate matters that have common issues of fact.29Id. § 1407(a); see also Wood, supra note 26, at 332–33. As the Southern District of Ohio explained in its website Introduction for In re Davol, Inc./C.R. Bard, Inc., Polypropylene Hernia Mesh Products Liability Litigation:

This Multidistrict Litigation (“MDL”) was created by Order of the United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation (“JPML”) on August 2, 2018. In its August 2, 2018 Order, the JPML found that the actions in this MDL “involve common questions of fact, and that centralization in the Southern District of Ohio will serve the convenience of the parties and witnesses and promote the just and efficient conduct of this litigation.” The JPML continued that, “[a]ll of the actions share common factual questions arising out of allegations that defects in defendants’ polypropylene hernia mesh products can lead to complications when implanted in patients, including adhesions, damage to organs, inflammatory and allergic responses, foreign body.”

Introduction – MDL 2846, U.S. Dist. Ct. S. Dist. of Ohio, https://perma.cc/FR4X-6SSW. They can decide to transfer the related matters to any district court, although they often look for courts that are convenient to the parties and have a willing judge who is able to handle the matter. The matters can only be consolidated for pretrial matters; once the issues are ready for trial, there is no further MDL jurisdiction over the matter.30See Lexecon Inc. v. U.S. Dist. Ct. for Dist. of Ariz., No. 95-70380, 1995 WL 432395, at *2 (9th Cir. July 21, 1995) (Kozinski, J., dissenting) (“Section 1407(a) authorizes the Multidistrict Panel to transfer cases for pretrial proceedings; after those proceedings are completed, and before trial, ‘[e]ach action so transferred shall be remanded by the panel.’ It’s hard to imagine a clearer statutory command . . . .” (emphasis omitted)). This limitation is significant: The MDL judge has no jurisdiction beyond pretrial proceedings. Once matters are through discovery and motion practice and are considered ready for trial, they must be remanded for trial.3128 U.S.C. § 1407(a) (“Each action so transferred shall be remanded by the panel at or before the conclusion of such pretrial proceedings to the district from which it was transferred unless it shall have been previously terminated . . . .” (emphasis added)).

If the JPML decides to grant consolidation of the MDL and finds a willing and acceptable judge, the matters already before the JPML will then be transferred to that MDL court. This takes a few days. The formation of an MDL will often trigger a wave of new cases being filed, as now it appears the subject of the MDL might allow for a viable claim.32David Goguen, Multidistrict Litigation (MDL) for Product Liability Cases, Nolo, https://perma.cc/RH4F-HDA6(“On the other hand, publicity surrounding an MDL can prompt new plaintiffs to file lawsuits; not a good thing for defendants.”). The cases transferred to the MDL court in the aftermath of the MDL formation are called “tag-along cases” and will be granted a “Conditional Transfer Order” to move the cases from their home court to the MDL court.33“A case may be transferred to a transferee court subsequent to a Transfer Order in a Conditional Transfer Order. The CTO is ‘conditional’ for seven days; at the expiration of that time, absent any objection, the CTO is made final and the case is transferred to a proceeding.” Catherine R. Borden, Emery G. Lee III & Margaret S. Williams, Centripetal Forces: Multidistrict Litigation and Its Parts, 75 La. L. Rev. 425, 431 (2014); see also Transfer Order at 1–2, In re Taxotere (Docetaxel) Prods. Liab. Litig., MDL No. 2740 (J.P.M.L. Sep. 30, 2020).

At this point, there are no formal rules directing how the transferee judge now in-charge of the MDL must handle all pretrial proceedings.34The lack of formal rules is another way MDLs are distinct from class action procedures, which are more formally regulated. See Bradt, supra note 6, at 791–92 (noting that due process concerns common to class actions “may be even more pronounced [in MDLs] since the MDL structure has fewer formal procedural protections than the class action”). There are, however, typical practices and recommendations from the Federal Judicial Center on how best to manage massive MDL dockets.35See Manual For Complex Litigation (Fourth) (2004) [hereinafter Manual for Complex Litigation]; Margaret S. Williams, Jason A. Cantone & Emery G. Lee III, Fed. Jud. Ctr. & Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Plaintiff Fact Sheets in Multidistrict Litigation Proceedings: A Guide for Transferee Judges (2019). For example, an MDL judge will typically request that the plaintiffs provide a suggested group of candidates to act as the “Plaintiffs Steering Committee (“PSC”),” which will serve as the liaison between the court and the hundreds or thousands of individual attorneys.36See David F. Herr, Multidistrict Litigation Manual § 9:15 (2019); John T. McDermott, The Transferee Judge—The Unsung Hero of Multidistrict Litigation, 35 Mont. L. Rev. 15, 16–19 (1974). The PSC is often divided into topical committees like “Law and Briefing,” “Discovery and Experts,” “Settlement,” and so forth.37See, e.g., Pretrial Order No. 7 at 1–2, In re Xarelto (Rivaroxaban) Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:14-md-02592 (E.D. La. Feb. 9, 2015) (appointing the PSC). There is typically a requirement to buy in to the PSC if appointed. See Manual for Complex Litigation, supra note 35, §§ 14.211, .14.215. This is called the “Common Benefit Fund.” See id. § 14.211. The PSC members also typically track the time they spend on PSC-related matters and submit statements of work to the court or Special Master, or a PSC committee designated to handle billing. And if the MDL resolves successfully, the hours billed will be repaid in keeping with what is available. See Pretrial Order No. 8 at 1–4, In re Xarelto, No. 2:14-md-02592 (E.D. La. Feb. 13, 2015) (“Establishing Standards and Procedure for Counsel Seeking Reimbursement for Common Benefits and Fees”); see also Manual for Complex Litigation, supra note 35, §§ 14.122, 14.211, 14.215–.216, 22.61. The judge also may decide, initially or at a later date, to appoint a special master for any purpose. Special masters and claims administrators have been used to track PSC billing submissions in the Taxotere MDL,38Pretrial Order No. 20 at 2, In re Taxotere, No. 2:16-md-02740 (E.D. La. Feb. 24, 2017) (“Appointment Kenneth W. DeJean as Special Master”). or direct settlement allocations in the Deepwater Horizon MDL.39Order at 1, In re Oil Spill by the Oil Rig “Deepwater Horizon” in the Gulf of Mex., on Apr. 20, 2010, No. 2:10-md-02179 (E.D. La. May 20, 2020) (“Approving Motion for Approval of Final Distribution of the Punitive Damages Portion of the Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. and Transocean Ltd. Settlement Agreements”)..

Particularly in the case of product liability MDLs, such as the big medical device and drug cases, the MDL judge may then call for the submission of a master petition. This is a “mega” petition that combines the commonly asserted causes of action.40See, e.g., Master Long Form Complaint, In re Davol Inc./C.R. Bard, Inc., Polypropylene Hernia Mesh Devices Liab. Litig., No. 2:18-md-02846 (S.D. Ohio Dec. 4, 2018). If there is a master petition, there usually is a “short form complaint” also used, which allows plaintiffs to adopt the master petition without re-asserting all of the separate paragraphs by simply completing and filing a brief worksheet with salient individual facts (name, address, place of injury, date of injury, etc.).41For example, the “Master Short Form Complaint” in the 3M Earplugs MDL is available online as a fillable form. Master Short Form Complaint and Jury Trial Demand, https://perma.cc/98HG-W2NM; cf. Pretrial Order No. 17: Order Governing Adoption of Master Complaint and Short Form Complaint for Filed Cases, In re 3M Combat Arms Earplug Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 3:19-md-02885 (N.D. Fla. Oct. 16, 2019) (adopting the master short form complaint for the 3M Earplugs MDL). This is achievable in the product liability cases where causes of action largely are identical across thousands of plaintiffs. While this is often treated as “standard practice,” however, there is in fact no true “standard” for MDLs, and every judge can determine on their own whether or not to require a master petition and short form complaints. In fact, there is legal argument against the practice,42Some MDL judges call Master Petitions administrative devices and do not consider them a valid pleading that can be targeted in motion practice. E.g., In re Vioxx Prods. Liab. Litig., 239 F.R.D. 450, 454 (E.D. La. 2006); In re Nuvaring Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 4:08MD1964, 2009 WL 2425391, at *2 (E.D. Mo. Aug. 6, 2009). This issue has been targeted by groups seeking to formalize MDL practice rules, as discussed here:

FRCP 7 does not formally recognize or regulate master complaints or answers despite their widespread use in MDL proceedings. In the absence of formal FRCP acknowledgement, some courts have declined to treat master complaints/answers as pleadings. This is particularly troublesome when it comes to deciding pretrial motions under, for example, FRCPs 8, 9, and 12. These rules apply specifically to pleadings, and MDL litigants are denied some of the traditional protections of the FRCP when courts decline to recognize master complaints/answers as pleadings. Consequently, FRCP 7 should be amended to formally recognize master complaints and answers as pleadings.

Hannah R. Anderson & Andrew G. Jackson, The Case for MDL Reform: Addressing the Flaws in a Critical System,Minn. St. Bar Ass’n: Bench & Bar of Minn., https://perma.cc/5L9W-8DR9.. and some judges require every plaintiff to file an individual and complete petition, like in the Zostavax MDL.43See In re Zostavax (Zoster Vaccine Live) Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:18-md-02848, 2019 WL 2137427, at *1 (E.D. Pa. May 2, 2019). In fact, in the Zostavax MDL, the judge dismissed multiple claims after the judge criticized the plaintiffs’ identical petitions, copied from an original filing, and determined these petitions did not adequately allege each individual case: “Each of the 173 complaints is full of boilerplate language unrelated to the individual case and is the antithesis of how a proper federal complaint should be drafted. The one-size-fits-all approach of plaintiffs’ counsel produced allegations that are absurd on their face as to every plaintiff.”44Id. However, Zostavax is unusual in this regard, and many MDLs are allowing the filing of standardized short form complaints.

Another preliminary issue that goes hand-in-glove with the question of a master petition is whether to allow for direct filing. Once an MDL is formed, cases will be transferred into the MDL court from the courts where they first originate. Practically, this occurs either automatically via the court clerk noting a designated “related case” on the civil cover sheet or through one of the parties notifying the JPML of a “tag-along” case and requesting transfer into the MDL. However, many MDL courts opt for allowing direct filing (i.e., permitting plaintiffs to file directly into the MDL court as a first step). This is procedurally awkward, because typically the plaintiffs do not have personal jurisdiction in the MDL court, and there is an argument that MDL judges cannot properly assert jurisdiction over direct-filed cases.45Direct-filed cases are filed under the court’s section 1331 diversity jurisdiction, given the broad tort-liability based nature of these kinds of claims. Bradt, supra note 6, at 795–96. Regardless, direct filing is a commonly used mechanism. For example, in the Xarelto MDL46In re Xarelto (Rivaroxaban) Prods. Liab. Litig., 65 F. Supp. 3d 1402 (J.P.M.L. 2016). from the Eastern District of Louisiana, the court order on direct filing declared:

In order to eliminate delays associated with the transfer to this Court of cases filed in or removed to other federal district courts and to promote judicial efficiency, any plaintiff whose case would be subject to transfer to MDL No. 2592 may file his or her complaint against all Defendants directly in MDL No. 2592 in the Eastern District of Louisiana.47Pre-Trial Order No. 9 at 1, In re Xarelto, No. 2:14-md-02592 (E.D. La. Mar. 24, 2015).

There are also often agreed-upon shortcuts in service of defendants as well, such as an emailed copy to counsel or a dedicated email address, or a mailed copy to a specific legal liaison.48This presents additional administrative issues for lawyers filing in new states in which they are not licensed, such as creating a temporary or limited CM/ECF license for MDL lawyers. See, e.g., Obtaining a CM/ECF Filing Login and Password, U.S. Dist. Ct. N. Dist. of Ga., https://perma.cc/HJ4M-QGQU (explaining that there is a special proceeding for attorneys to file in the MDL and providing a link to request CM/ECF access in the Ethicon Herniamesh MDL proceeding before Judge Richard Story).

As Bradt points out in The Shortest Distance, there are numerous reasons why the administrative short-cut of direct filing into an MDL is beneficial.49Bradt, supra note 6, at 796. From the plaintiff practitioners’ standpoint, this skips the delay caused by waiting for transfer and permits access to the PSC and their guidance, immediate participation in potential bellwether plaintiff pools,50The Federal Judicial Center has an informative pocket guide on the selection of bellwethers. Melissa J. Whitney, Fed. Jud. Ctr. & Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Bellwether Trials in MDL Proceedings: A Guide for Transferee Judges (2019). Recall that the governing statute allows the MDL transferee court to handle all pretrial proceedings. Id. at 1. Once it is time for trial, the MDL transferee court no longer has jurisdiction over the individual suits. Id. at 3. However, it is an established practice that the MDL judge holds a few “test case[s],” termed “bellwether trial[s].” Id. Once a few bellwether trials are complete, the idea is that both sides will be able to determine the value, if any, of the case and may be able to extrapolate a general, MDL-wide settlement. See id. at 3–4.

The MDL transferee judge may ask for Lexecon waivers—waivers of venue and personal jurisdiction objections by defendants. See id. at 11–15. These waivers, named after a Supreme Court decision holding that an MDL court has no statutory authority to try cases that did not originate in the transferee judge’s district, allow the transferee judge to hold a trial for transferred-in cases. See id. at 11. If the defendants agree to a Lexecon waiver, then potentially any case within the MDL is eligible to be a bellwether-trial case. See id. at 12–13 (quoting Case Management Order No. 11, In re Bard IVC Filters Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:15-md-02641 (D. Ariz. May 5, 2016)). If, however, the defendants refuse to waive their venue and jurisdiction objections, then the only potential bellwether cases are those that arose in the district where the transferee judge sits—or can sit by agreement. For instance, in the Taxotere MDL proceedings in the Eastern District of Louisiana, the defendants would not waive their Lexecon objections and thus the bellwether pool consisted of residents within the Eastern District of Louisiana, as well as residents of other districts in Louisiana and Mississippi that the Taxotere MDL judge could travel to and hold trials in by agreements with the judges in those districts. See Case Management Order No. 8 at 1–2, In re Taxotere (Docetaxel) Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:16-md-02740 (E.D. La. Oct. 11, 2017).

Another issue is how many bellwether plaintiffs should be tried or worked up for potential trial. There are a great number of systems for this. Some judges tell each side to select some number of bellwether pool plaintiffs, and those plaintiffs are then each worked up and individually deposed, with individual expert witnesses and so forth. Whitney, supra note 50, at 28. Then there is a trial selection, which can involve allowing “strikes” by each party of a certain number of bellwether pool members until only a few are left or a random selection by the court itself, or anything else. Id. The entire bellwether pool can also be randomly selected, and there can be separate pools of potential trial plaintiffs for each planned trial, or a row of trials planned for a single pool of plaintiffs. Id. There are no limits to the MDL courts’ options here. See Manual for Complex Litigation, supra note 35, § 20.132. and access to online document repositories and plaintiff fact sheet databases, as well as other time-sensitive issues.51See Manual for Complex Litigation, supra note 35,§ 20.313. This also avoids confusion and litigation at the home-court level that can occur prior to transfer—some courts are extremely efficient at assigning cases, setting up initial scheduling conferences, and ordering disclosures, meetings with magistrates, and so forth, such that even a brief waiting period in the home court prior to transfer can create a series of expectations that may then travel with that case into the MDL.52From The Shortest Distance:

Ultimately, direct filing creates numerous efficiencies for all parties. The JPML is not burdened with transferring cases to and from home districts. Home district judges and clerks’ offices need not undertake administrative burdens associated with cases destined for transfer and which will likely not return. The MDL court retains complete control over a greater portion of the overall pool of cases for trial and facilitation of global settlement, which is likely why MDL judges encourage the practice. These benefits extend to the parties as well, particularly defendants and firms representing a significant number of plaintiffs. Lodging all of the cases in a single court in the first instance more seamlessly aggregates the litigation.

Bradt, supra note 6, at 796. This reasoning is reflected by the decision in Interstate Service Provider, Inc. v. Jordan, in which a court declined to stay proceedings despite a pending motion to transfer to an MDL: “The orders, pretrial proceedings, and jurisdiction of a transferor court are unaffected when a party petitions the JPML for transfer and consolidation.” No. 4:21-cv-267, 2021 WL 2355384, at *2 (E.D. Tex. June 9, 2021) (citing R. Proc. U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig. 2.1(d); Morales v. Am. Home Prods. Corp., 214 F. Supp. 2d 723, 725 (S.D. Tex. 2002)). Similarly, in Rivers v. Walt Disney Co., the court notes: “In other words, a district judge should not automatically stay discovery, postpone rulings on pending motions, or generally suspend further rulings upon a parties’ motion to the MDL Panel for transfer and consolidation.” 980 F. Supp. 1358, 1360 (C.D. Cal. 1997). Direct filing would have avoided these outcomes. Where the direct-file option is available, it tends to become the favored procedure.53See U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., supra note 22, at 3.

Judge Eldon Fallon of the Eastern District of Louisiana, who has built a reputation of experience with large MDLs, has also written about the benefits of the direct filing.54See Eldon E. Fallon, Jeremy T. Grabill & Robert Pitard Wynne, Bellwether Trials in Multidistrict Litigation, 82 Tul. L. Rev. 2323, 2355–60 (2008). In his 2008 article about the possibilities of direct filing, he and his co-authors observe:

[T]he transferee court permits plaintiffs who do not reside in the judicial district encompassing the transferee court to file cases directly into the MDL. This procedure obviates the expense and delay inherent with plaintiffs having to file their cases in local federal courts around the country after the creation of an MDL and then waiting for the MDL Panel to transfer the “tag-along” cases to the transferee court. In addition, it eliminates the judicial inefficiency that results from two separate clerk’s offices having to docket and maintain the same case and three separate courts (the transferor court, the MDL Panel, and the transferee court) having to preside over the same matter.55Id. at 2355–56 (footnotes omitted).

Direct filing of course is problematic, as it means that a court is granting itself jurisdiction over a diversity tort matter that could not have been brought before it, without first obtaining transfer jurisdiction through the JPML. In the C.R. BardHernia Mesh MDL56In re Davol, Inc./C.R. Bard, Inc., Polypropylene Hernia Mesh Prods. Liab. Litig., 316 F. Supp. 3d 1380 (J.P.M.L. 2018). before the Southern District of Ohio, the defendant company is based in New Jersey and plaintiffs are located all over the country, such that an Oregon plaintiff could sue a New Jersey defendant alleging Oregon state-law-based claims, yet file in Ohio.57Master Long Form Complaint at 2–3, In re C.R. Bard Hernia Mesh, No. 2:18-md-02846 (S.D. Ohio Dec. 4, 2018). This is an administrative shortcut that also violates a fundamental rule of procedure: Article III courts have limited jurisdiction, and this is an expansion of that jurisdiction.58This is not the first expansion of jurisdiction undertaken by MDL judges. For a brief time, MDL judges would also hold trials for individual cases—often test cases or bellwether trials—despite not having trial jurisdiction over the matters tried. This was stopped by the Supreme Court decision in Lexecon Inc. v. Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach. 523 U.S. 26, 34–36 (1998). The Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the text of section 1407(a), which states that the cases “shall be remanded,” does not admit of any judicial discretion to then try the matters consolidated in the MDL. Id. at 35 (quoting 28 U.S.C. § 1407(a)). Hence the term Lexecon waiver, which parties can agree to if they want a case tried by the MDL judge despite that judge’s lack of personal jurisdiction over the parties. A more typical practice is now to select bellwether trial plaintiffs from those plaintiffs over whom the court can exercise jurisdiction. See, e.g., Case Management Order No. 3 at 1, In re Taxotere (Docetaxel) Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:16-md-02740 (E.D. La. July 21, 2017) (stating that the original set of bellwether plaintiffs were all from the Eastern District of Louisiana). Of course, it is also merely a shortcut, in that the JPML was inevitably going to transfer pretrial handling of the case to that MDL court, and the MDL court cannot assert jurisdiction over the ultimate trial of the decision from cases arising in outside jurisdictions. But the ZostavaxMDL-handling judge, who, for example, has resisted efforts to allow short form complaints and direct filing into the MDL he is handling,59See In re Zostavax (Zoster Vaccine Live) Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:18-md-02848, 2019 WL 2137427, at *1 (E.D. Pa. May 2, 2019). is certainly not legally wrong. Moreover, they have avoided the direct-filing home-state issues explored below entirely, by instead having plaintiffs select a home-state venue through the traditional method of physically filing there and going through the formal steps of being transferred to the MDL court after filing at home.60See James M. Beck, MDL Direct Filing & Personal Jurisdiction, Drug & Device L. (Oct. 16, 2017), https://perma.cc/2UF9-DPZA. James Beck reports at length on the problems inherent in allowing direct filing to develop entirely outside of the rules of civil procedure and concludes that the practice is inherently unfair to defendants. Id.(“[W]e believe that there is no constitutional basis for personal jurisdiction in direct-filed MDL cases, and defendants should not do plaintiffs any favors by voluntarily agreeing to such procedures.”).

In any event, the numbers do not lie: Where direct filing is available, plaintiffs overwhelmingly choose to file directly.61See U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., supra note 22, at 5. And we currently operate in a world where tens of thousands of directly filed cases are handled by MDL judges up to the point of remand and trial.62See id. Now that we are in the world of direct filing, the next step is to look at where these “homeless” cases go upon remand. In fact, the word “remand” is a difficult one to use here, as it effectively requires a return of a case.63“The act or an instance of sending something (such as a case, claim, or person) back for further action.” Remand, Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). The direct-filed case has only ever existed as a case filed in the MDL court; truly there is no “returning” that case.

This issue has been discussed in theory, but the actual practice has been extremely limited until recently, as MDLs are a relatively recent development in jurisprudence and almost all of the large product liability MDLs resolve through settlement. There are now, however, enough mega-MDLs advancing to the point where decisions are regularly being made about what state law should apply to a case directly filed in the “wrong” jurisdiction. Part II will discuss the issue of applying state law to a case transferred due to MDLs, which should, in theory, provide guidance on how directly filed cases should also be handled when choice-of-law issues arise, while later sections of this Article will turn to what has actually been happening.

II. The MDL Choice-of-Law Problem

The question of where to send direct-filed cases once they are ready for trial arises out of a solution for another, possibly more significant issue: The question of which law to apply in MDL cases involving multiple jurisdictions. It hardly needs to be said that states each handle tort claims in different ways, from statutes of limitations, to the allowance of punitive damages, to considerations of joint-and-several liability, mitigation, express warranty liability, and so on. As summarized by Professor Larry Kramer, “different states with legitimate interests have made different judgments about how to handle tort problems. Different outcomes are thus both expected and acceptable.”64Kramer, supra note 3, at 579. How then to reconcile these natural differences in a centralized lawsuit in a single location?

The 1941 Supreme Court decision in Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co.65313 U.S. 487 (1941). set the stage for the choice-of-law problem now faced by MDL courts.66See id. at 496. Klaxon was not itself an MDL case but rather involved a breach of contract, filed in a Delaware federal court, between a New York corporation and a Delaware corporation, under a contract made in New York.67Id. at 494. New York had a rule mandating the addition of prejudgment interest on an award.68Id. at 495. Delaware apparently did not.69Seeid. at 496. The jury deciding the case was not asked to determine whether prejudgment interest should be awarded as the New York party presumed it would, and the Delaware party presumed it would not.70See id. at 494–95.

The Supreme Court held that a federal court, sitting in diversity, must follow the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it is sitting.71Klaxon, 313 U.S. at 486–87. A federal court in Delaware, hearing a case under 28 U.S.C. section 1331, must apply Delaware choice-of-law rules. As a result, there would be no prejudgment interest for poor Stentor Electric (a lesson in the danger of making assumptions about the choice-of-law analysis that will be echoed further below). As Bradt expressed in The Shortest Distance, “states’ choice-of-law rules represent a state’s substantive decision on the scope of its law, and diversity jurisdiction does not warrant departure from those rules.”72Bradt, supranote 6, at 780; see also Kramer, supra note 3, at 571.

This remained the consistent policy of the Supreme Court, as expressed years later in Van Dusen v. Barrack,73376 U.S. 612 (1964). which involved a multi-state plane crash with two different procedural rules on how to bring wrongful death cases.74Id. at 613–14. The defendants sought to transfer all matters to a single court, which raised the concern that cases properly filed in one state would be considered improperly filed under the wrongful death rules when filed in another state, and thus subject to dismissal due to the change in venue.75Id. at 614. The Court dispelled that concern in its ruling, declaring that the transfer of a case to a new jurisdiction for purposes of aggregation was a “housekeeping measure” and could not change the law that was intended originally to apply to the case.76Id. at 636, 639 (“[W]here the defendants seek transfer, the transferee district court must be obligated to apply the state law that would have been applied if there had been no change of venue.”). The Van Dusen opinion is notable for its recognition of “plaintiff’s venue privilege.”77Id. at 633–35. It noted that because “§ 1404(a) operates on the premise that the plaintiff has properly exercised his venue privilege,” plaintiffs should then be allowed “to retain whatever advantages may flow from the state laws of the forum they have initially selected.”78Id. at 633–34; see alsoAntony L. Ryan, Principles of Forum Selection, 103 W. Va. L. Rev. 167, 197 (2000).

Klaxon and Van Dusen pre-date the passage of the MDL statute in 196879See Overview of Panel, U.S. Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., https://perma.cc/X9LH-U3G9 (“The United States Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, known informally as the MDL Panel, was created by an Act of Congress in 1968—28 U.S.C. §1407.”). but their holdings have been carried forward and applied in the MDL context. The Supreme Court explained in Ferens v. John Deere Co.80494 U.S. 516 (1990). that in standard, non-MDL cases a transfer of forum “does not change the law applicable to a diversity case.”81Id. at 523. The Supreme Court has explained that section 1404(a), which authorizes transfers for the convenience of parties and witnesses, is “a housekeeping measure that should not alter the state law governing a case under Erie.”82Id. at 526; accord Van Dusen, 376 U.S. at 639 (“[W]here the defendants seek transfer, the transferee district court must be obligated to apply the state law that would have been applied if there had been no change of venue.”). The question then arises, what happens in the MDL context? Bradt describes this as a booming area of litigation; the boom has continued at least to hold steady—if not expand—accounting for a huge percentage of cases heard in federal court every year.83See Bradt, supra note 6, at 762; see also Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics 2020, U.S. Cts., https://perma.cc/A87V-CYAA (noting that in 2020, “[p]ersonal injury/product liability filings surged 97 percent (up 45,523 cases) as cases involving other personal injury/product liability climbed by 55,121 filings (up 548 percent). Most were part of multidistrict litigation filed in the Northern District of Florida that alleged injuries sustained while using 3M Combat Arms earplugs”). And of those, a massive majority are the classic products liability MDLs that generate the thousands of billboard, radio and television—and now social media—ads that are encountered everywhere.84A Reuters Legal article reported that “[l]awyers and referral services have from January to May spent $67 million on mass tort TV advertising, up 6.6% from the same time last year, when law firms aired fewer spots that cost more money, according to data analyzed by X Ante.” Nate Raymond, Mass Tort TV Advertising Jumps Amid Coronavirus Pandemic, Reuters Legal (July 6, 2020, 11:06 AM), https://perma.cc/L5NG-UMAE.

Under 28 U.S.C. section 1407, MDL courts possess limited authority to rule on pretrial motions and handle pretrial matters like discovery. This often means MDL judges oversee and rule on motions probing the adequacy of the claims under various state laws—which may mean they are resolving state-law-based-claims for a state in which they do not sit. The choice of law for these pretrial motions depends on whether they involve federal or state law.

When analyzing questions of federal law, the transferee court should apply the law of the circuit in which it is located. When considering questions of state law, however, the transferee court must apply the state law that would have applied to the individual cases had they not been transferred for consolidation.85In re Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) Implants Prods. Liab. Litig., 97 F.3d 1050, 1055 (8th Cir. 1996) (citation omitted).

In cases based on diversity jurisdiction, which comprise the bulk of massive MDLs consolidated for product liability claims, the applicable choice-of-law rules are those of the states where the actions were originally filed.86In re Air Disaster at Ramstein Air Base, Ger., on 8/29/90, 81 F.3d 570, 576 (5th Cir.) (“Where a transferee court presides over several diversity actions consolidated under the multidistrict rules, the choice of law rules of each jurisdiction in which the transferred actions were originally filed must be applied.”), amended by Perez v. Lockheed Corp., 88 F.3d 340 (5th Cir. 1996); see also Carlson v. Bos. Sci. Corp., No. 2:13-cv-05475, 2015 WL 1956354, at *2 (S.D. W. Va. Apr. 29, 2015); In re Digitek Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:08-md-01968, 2010 WL 2102330, at *7 (S.D. W. Va. May 25, 2010); In re Air Crash Disaster near Chi., Ill. on May 25, 1979, 644 F.2d 594, 610 (7th Cir. 1981). Of course, this rule assumes that these actions were filed in a home court and then transferred elsewhere.

In accord with the Supreme Court’s view of section 1404(a), transfers caused by the JPML are similarly treated as simply “a change of courtrooms.”87Van Dusen, 376 U.S. at 639 (“A change of venue under § 1404(a) generally should be, with respect to state law, but a change of courtrooms.”). The location of the MDL court itself is an “accident of bureaucratic convenience” that is not intended to “elevate the law of the MDL forum.”88Wahl v. Gen. Elec. Co., 786 F.3d 491, 496 (6th Cir. 2015); see also id. at 498 (“If plaintiffs could avail themselves of the law of the MDL-court forum, every plaintiff in an MDL case would be able to choose the law of a state that is not an appropriate venue.”). We should not change our usual choice-of-law practices solely for mass litigation, as summarized by Kramer:

Because choice of law is part of the process of defining the parties’ rights, it should not change simply because, as a matter of administrative convenience and efficiency, we have combined many claims in one proceeding; whatever choice-of-law rules we use to define substantive rights should be the same for ordinary and complex cases.89Kramer, supra note 3, at 549.

The Federal Judicial Center, which provides information and assistance to MDL judges, notes that this leaves MDL courts handling numerous cases that would not otherwise fall within its jurisdiction, and thus handling cases from states with varying substantive and procedural laws:

Differences in the substantive law governing liability and damages may substantially affect discovery, trial, and settlement. In dispersed, multistate defective products litigation, choice of law issues may be especially problematic because a wide range of state laws may apply, and the state in which the action is pending may not have a significant relationship with many of the plaintiffs, with the defendants, or with the activities that are subject to the litigation. 90Barbara J. Rothstein & Catherine R. Borden, Fed. Jud. Ctr. & Jud. Panel on Multidistrict Litig., Managing Multidistrict Litigation in Products Liability Cases: A Pocket Guide for Transferee Judges 30 (2011). The pocket guide for transferee judges in products liability cases goes on to suggest ways to handle the potentially overwhelming task of analyzing up to 50 states’ laws: If the choice of law and subsequent analysis show little relevant difference in the governing law, or that the law of only a few jurisdictions applies, you might address these differences by creating subclasses or by other appropriate grouping of claims. When different state laws apply, you might ask the parties to research the feasibility of organizing cases based on the similarity of the applicable laws. If the cases are consolidated for pretrial purposes, lead counsel can file “core” briefs on dispositive motions based on the most widely applicable or otherwise most significant state substantive law. Variations in state laws can be addressed separately through supplemental briefs, which can be prepared by lawyers whose clients assert that a different law applies to some or all of their cases. Alternatively, you may rule on a motion in cases under one state’s law and issue an order to show cause why the ruling should not apply to the other cases. Id. (footnote omitted).

This was echoed by the judge handling the Valsartan MDL:91In re Valsartan, Losartan, & Irbesartan Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 1:19-md-02875, 2021 WL 307486 (D.N.J. Jan. 29, 2021).

It is nearly an unassailable conclusion that the laws of the fifty states with respect to some of the causes of actions will conflict and affect the outcome of the case. Even a cursory review of the law confirms this conclusion. For instance, under New York’s law for negligent misrepresentation a plaintiff is required to show either privity of contract between the parties or a relationship approaching privity, while Texas does not require such a showing.92Id. at *8 (first citingParrott v. Coopers & Lybrand, L.L.P., 741 N.E.2d 506, 508 (N.Y. 2000) (stating that in a claim of negligent misrepresentation a plaintiff must show “either actual privity of contract between the parties or a relationship so close as to approach that of privity”); and then citing Averitt v. PriceWaterhouseCoopers L.L.P., 89 S.W.3d 330, 335 (Tex. App. 2002) (stating that privity is not required to hold an accountant liable to a third party arising from the accountant’s misrepresentations)).

In her article on courts’ ability to handle complex conflicts-of-law issues, Professor Katherine Florey suggests that courts are best equipped to handle “little” conflicts of law, where they do not need to analyze far-reaching questions of social values and policy.93See Katherine Florey, Big Conflicts Little Conflicts, 47 Ariz. St. L.J. 683, 688–89, 754(2015). MDLs, at least legally, are often fairly straightforward tort cases: There is the use of X medical device; there is Y injury allegedly caused by that medical device; there are damages as a result. Big policy-level questions are typically not implicated. The only complicating factor artificially overlaid onto this basic tort claim premise is the procedural transfer and consolidation of nationwide suits into one forum. This is not to understate the complexity, given the potential for over fifty individual jurisdictions to be involved in a single MDL, but the issue is more the “fiendishly difficult problems of administration”:94Id. at 688.

It is fair to say that choice-of-law issues represent one of the most serious obstacles—if not the most serious—to consolidating cases, even where joinder might otherwise serve the interests of efficiency and justice. Choice-of-lawproblems have played a significant role in rolling back the national mass-tort class action, and threaten to do the same in undermining the usefulness of MDL. Further, even when choice-of-law issues do not interfere with aggregation, they pose fiendishly difficult problems of administration for judges, who sometimes stretch choice-of-law doctrine almost to the breaking point to avoid the unmanageable complexity that might otherwise result.95Id. at 687–88 (emphasis omitted) (footnotes omitted).

Florey critically reviewed a choice-of-law struggle in a multi-state airplane crash suit involving potential punitive damages.96Id. at 739–40. She concluded that the court could be faulted “for engaging in somewhat slipshod reasoning and failing to apply the relevant methodologies carefully” in determining the applicable law to a determination of whether punitive damages were available.97Id. at 740–41. Kramer also casts doubt on the abilities of courts to handle complex, multi-state analyses in complex cases. Kramer, supra note 3, at 552 (“Under Klaxon Co. v. Stentor Electric Manufacturing Co., a federal court has no power to innovate and must apply the choice-of-law rules of the state in which it sits. Where claims have been transferred from other districts—at least where the transfer is based on 28 U.S.C. § 1404 or § 1407, as is usually the case—Van Dusen v. Barrack further constrains the court by requiring it to apply the whole law of the transferor court, including its choice-of-law rules. This being so, it is remarkable how often courts adjudicating mass actions nevertheless find that one law applies to all the claims or to each issue. The most revealing examples are in MDLs under 28 U.S.C. § 1407.”). Conversely, the judge handling the Valsartan MDL considered the required fifty-two-jurisdiction analysis “laborious” but straightforward and necessary:

The short-form complaints directly filed in this MDL contained designations of venue that spanned the fifty states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. Therefore, because of this stipulation and order, for the actions directly filed in this MDL, we must conduct a choice of law analysis for each of the fifty states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. This is so . . . because the individual actions, whether transferred to or directly filed in the MDL, span all fifty states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico. . . . While this choice of law analysis may seem like a particularly laborious task, the answer is quite simple—the law of each plaintiffs’ home state should be applied.

In re Valsartan, Losartan, & Irbesartan Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 1:19-md-02875, 2021 WL 307486, at *8 (D.N.J. Jan. 29, 2021).

Regardless, why was an MDL court determining whether punitive damages were available? Because the defendants and plaintiffs were from various states that did and did not allow punitive damages awards. Had the plaintiffs been able to designate their choice of jurisdiction upon entry to the MDL—signaled either by a designation on a short form complaint or by filing in that jurisdiction and awaiting transfer from it—the criticized multi-state analysis could have been foreclosed entirely. MDL courts, arguably, should not ever need to make damages-related determinations, but realistically, MDL courts often establish discovery parameters and settlement protocols that require state-law-specific information, such as whether punitive damages are awardable, or resolve other individual-case-level issues before remand.98See, e.g., In re Bos. Sci. Corp., Pelvic Repair Sys. Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:12-md-2326, 2015 WL 1637722, at *1 (S.D. W. Va. Apr. 13, 2015) (“In an effort to efficiently and effectively manage this massive MDL, I decided to conduct pretrial discovery and motions practice on an individualized basis so that once a case is trial-ready (that is, after the court has ruled on all Daubert motions, summary judgment motions, and motions in limine, among other things), it can then be promptly transferred or remanded to the appropriate district for trial.”). MDL courts also often hear preliminary motions to dismiss that will turn on state-law analysis.99See, e.g., In re JUUL Labs, Inc., Mktg. Sales Prac. & Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 3:19-md-02913, 2021 WL 3112460, at *1, *8–11 (N.D. Cal. July 22, 2021) (conducting a multi-state analysis when addressing motions to dismiss individual plaintiffs).

The MDL court gives a home to cases from across the nation for streamlining purposes; it does not change the inherent nature of those individual cases as being individual cases filed in specific home jurisdictions. That is an important distinction between MDLs and class actions—the individual MDL plaintiff remains the master of their case throughout, despite being bodily lifted from, for example, Louisiana, and deposited in Ohio for pretrial purposes.100For a detailed discussion of the plaintiff’s choice of forum and the “master of the case” concept, see Ryan, supra note 78, at 168–69. The proceedings in Ohio did not arise under Ohio products liability law and Louisiana choice-of-law rules should still be applied to the claim.

This is well illustrated in Crespo v. Merck & Co.,101No. 13-cv-2388, 2020 WL 5369045 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 8, 2020). in which a case was filed in New Jersey and then transferred by action of the JPML to the Eastern District of New York for consolidation with an MDL. Considering a motion for summary judgment in the individual suit, the judge noted that, despite the case currently being in a New York courtroom, this was a New Jersey case, and thus he would apply New Jersey choice-of-law rules.102Id. at *2 (“Because this action was filed in New Jersey, I apply New Jersey’s choice-of-law rules.”). The court then noted the two jurisdictions with potential interest in the action: “New Jersey is the state in which plaintiffs filed this action, and the state in which defendants are incorporated, have their principal place of business, and made decisions regarding the labeling and marketing of Propecia. Florida is the state in which Mr. Crespo was prescribed, purchased, and took Propecia.”103Id. Although Florida was the place of injury and place of the plaintiff’s residence, Florida was not the home state, as the matter was originally filed in New Jersey and thus the judge applied New Jersey’s choice-of-law rules.104Id. at *5. Applying those rules, the New York MDL judge found that New Jersey’s interests in the plaintiff’s express warranty claims trumped the interests of Florida, and thus New Jersey’s statute of limitations for that claim would apply, barring the claim as untimely.105Id. The same analysis applies in other cases where there is no direct filing. See, e.g., In re Davol, Inc./C.R. Bard, Inc., Polypropylene Hernia Mesh Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:18-md-02846, 2020 WL 5223363, at *6 (S.D. Ohio Sept. 1, 2020) (“Because Plaintiff filed his original complaint in the United States District Court for the District of Utah before this case was transferred to this Court, the parties and this Court agree that Utah choice-of-law principles determine the substantive law applicable to Plaintiff’s claims. ‘Utah uses the “significant relationship” standard for choice of law issues in tort claims.’” (quoting Bulletproof Techs., Inc. v. Navitaire, Inc., No. 2:03-cv-00428, 2005 WL 2265701, at *7 (D. Utah Aug. 29, 2005))). Note that, under the “rule” adopted by many MDL judges with regard to direct-filed cases, this case would have been analyzed as a Florida case, using Florida choice-of-law rules, if it had been directly filed into the MDL and treated like the Sanchezdirect-filed cases. See discussion infra Part V.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit was extremely clear on this issue in Sutherland v. DCC Litigation Facility, Inc. (In re Dow Corning Corp.),106778 F.3d 545 (6th Cir. 2015). which expressly carried forward the reasoning of Van Dusen and Ferens into the MDL context:

There is no question that if this were a diversity case whose venue was transferred pursuant to the multidistrict litigation statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1407, or general change-of-venue statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1404, the district court would be bound to apply North Carolina’s choice of law rules. In Van Dusen v. Barrack and Ferens v. John Deere Company, the Supreme Court made clear that normally the appropriate state’s choice of law rule attaches when and where the plaintiff files her complaint and then travels with the case.107Id. at 549–50; see also In re Bendectin Litig., 857 F.2d 290, 305 (6th Cir. 1988).

District judges presiding over MDLs have appeared to embrace the same conclusion the Sixth Circuit reached in In re Dow Corning—when presiding over an MDL:

[T]he choice-of-law principles that the transferor court will apply are those of the [s]tate where the transferor court sits, and not, for example, the choice-of-law principles of Ohio, where the MDL court sits. This is because: (1) “[i]n diversity cases [a court must] apply the choice-of-law rules . . . of the forum state;” and (2) “[i]n MDL cases, the forum state is typically the state in which the action was initially filed before being transferred to the MDL court.”108In re Welding Fume Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 1:03-cv-17000, 2010 WL 7699456, at *12 (N.D. Ohio June 4, 2010) (first quoting Centra, Inc. v. Estrin, 538 F.3d 402, 409 (6th Cir. 2008); and then quoting In re Welding Fume Prods. Liab. Litig., 245 F.R.D. 279, 295 n.90 (N.D. Ohio 2007)); see also id. (“Given that a case remanded by this MDL Court to a transferor court was originally filed in either that transferor court, or in a State court within that federal district before removal, it is the choice-of-law principles of the State where the transferor court sits that will apply.”). This reasoning also appears in the Eighth Circuit’s decision in In re Bair Hugger Forced Air Warming Devices Products Liability Litigation: [S]ince Petitta filed his federal complaint directly in the District of Minnesota, where the MDL is located, and his case was never transferred between federal venues. But he filed in the District of Minnesota only because the MDL court’s standing order directed him to do so. If not for that order, he would have filed in the Southern District of Texas, his case would have been transferred to the MDL in the District of Minnesota, and our precedent would guide us to apply Texas law. 999 F.3d 534, 538–39 (8th Cir. 2021).

This principle was applied in the earlier-decided Guidant Corp. Implantable Defibrillators MDL.109See In re Guidant Corp. Implantable Defibrillators Prods. Liab. Litig., 489 F. Supp. 2d 932, 934–35 (D. Minn. 2007) (applying the choice-of-law rules of the transferor forum in a case transferred by the MDL Panel and selected as the first bellwether trial). In that case, the plaintiff filed in California and was transferred via a JPML order to the MDL court in Minnesota.110Id. at 934. The plaintiff then adopted the master complaint and argued that Minnesota’s choice-of-law rules should apply, as though the case had originated in Minnesota.111Id. at 935. The court disagreed and applied the rule from Van Dusen, holding instead that because the plaintiff filed in California, California’s choice-of-law rules apply.112Id. at 936. Subsequent transfer to Minnesota and adoption of a master complaint filed in Minnesota did not erase or undo the original California filing.113Id.

Per Wahl v. General Electric Co.,114786 F.3d 491 (6th Cir. 2015). this application of the home-state’s choice-of-law rules includes both procedural rules, like statutes of limitations, and substantive rules, such as the availability of punitive damages.115See id. at 495–96 (citing Ferens v. John Deere Co., 494 U.S. 516, 531 (1990)) (emphasizing the Supreme Court’s application of the Van Dusen choice-of-law rule to the question of substantive law). The MDL judge must turn to the law of the true home state of an individual suit that is consolidated within the MDL for all purposes.116See id. at 496–97. Other courts agree with this analysis, applying the home-state rules across all types of procedural and substantive issues, like statutes of limitations, how to file suit on behalf of a deceased party, and the applicability of punitive damages.117See, e.g., Sanchez v. Bos. Sci. Corp., No. 2:12-cv-05762, 2014 WL 202787, at *4 (S.D. W. Va. Jan. 17, 2014) (“I will follow the better-reasoned authority that applies the choice-of-law rules of the originating jurisdiction . . . . Therefore, California choice-of-law rules will govern the selection of the statute of limitations.”); In re Bos. Sci. Corp., Pelvic Repair Sys. Prods. Liab. Litig., No. 2:12-md-2326, 2015 WL 1637722, at *4 (S.D. W. Va. Apr. 13, 2015) (applying home forum of Virginia’s choice-of-law analysis to questions of punitive damages).

Numerous judges handling MDL cases across the country agree that it is the originating court’s conflict-of-laws standards that are applied to each individual consolidated case.118E.g., In re Conagra Peanut Butter Prods. Liab. Litig., 251 F.R.D. 689, 693 (N.D. Ga. 2008) (“[A]ll states in which the transferor court of an individual action sits are considered forum states, and an independent choice of law determination is necessary for the states of all transferor courts.”).. This leads to complex choice-of-law decisions that have to be repeated for each individual plaintiff from a different state.119See, e.g., In re Takata Airbag Prods. Liab. Litig., 193 F. Supp. 3d 1324, 1333 (S.D. Fla. 2016) (“Accordingly, Florida’s choice of law rules apply to Birdsall’s claims because his claims were filed directly in the Southern District of Florida. Alabama’s choice of law rules apply to Pardue’s claims because her case was transferred into the MDL from the Northern District of Alabama. And Pennsylvania’s choice of law rules apply to Vukadinovic’s claims because his case was transferred into the MDL from the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.”). But it also makes sense: The MDL statute provides limited jurisdiction over individual MDL cases in order to address large, unified issues, not individualized state law inquiries. Where an individualized state law inquiry is required—say, how a deceased plaintiff should be represented in the MDL—the location of the MDL should not play a role in the outcome of that decision, nor was the MDL itself created to answer that type of question. The MDL court is not the home of any case, but rather a holding place where common issues are addressed without changing the outcome of individual issues.

While this is almost universally accepted as true, there are a few outlier decisions that apply the state-law rules of an MDL court’s own state (without even mentioning the underlying choice-of-law decision being made) to individual suits consolidated within the MDL. Byers v. Lincoln Electric Co.120607 F. Supp. 2d 840 (N.D. Ohio. 2009). is cited in Wahl as standing for the proposition—which Wahl disagrees with—that an MDL plaintiff’s case is governed by the law where the MDL is filed.121Wahl, 786 F.3d at 496. But that conclusion overstates the ruling in Byers: The Byerscase was specifically filed in Ohio, where two of the defendants were located, and Byers himself sought the application of Ohio law.122Byers, 607 F. Supp. 2d at 843, 846.. This was not a larger announcement of a new legal practice, but rather more of a coincidence that an Ohio MDL court handled an Ohio choice-of-law decision and ultimately applied Ohio law, as the parties all seemed to desire.

The Vioxx MDL123In re Vioxx Prods. Liab. Litig., 478 F. Supp. 2d 897 (E.D. La. 2007). opinion is more significant, particularly given that a highly experienced and sought-after MDL judge, Judge Fallon from the Eastern District of Louisiana, appeared to create a new rule that deviated significantly from the MDL norm—and applied that norm specifically to direct-filed cases.124See id. at 904 n.2. The Vioxx decision, although not expressly cited by the later-discussed cases that appear to create a new rule for direct-filed cases only, may in fact be the progenitor for the disparate treatment of direct-filed versus transferred cases further explored in Part V below.

In Vioxx, Judge Fallon went to great lengths to draw a distinction between cases transferred from their home courts to the MDL and cases filed directly in the MDL through the direct-file mechanism.125See id. at 903.. The former, he agrees, should have their home-state choice-of-law apply.126See id. The latter, however, he insists, have availed themselves of Louisiana choice-of-law rules.127Id. at 903–04.. This part of the ruling, however, has not been adopted by any other judge to date.128However, Judge Fallon continues to apply his Vioxx rule in other MDLs. See In re Xarelto (Rivaroxaban) Prods. Liab. Litig., MDL No. 2592, Civil No. 15-cv-03913, 2021 WL 2853069, at *10 (E.D. La. July 8, 2021) (“Unlike the majority of cases in an MDL, which are filed in, or removed to, federal courts across the country and transferred to the MDL court by the Judicial Panel on Multidistrict Litigation, the present case was directly filed into the MDL by two citizens of Louisiana and one citizen of Illinois. For this reason, Louisiana choice-of-law analysis applies to this case.” See In re Vioxx Prods. Liab. Litig., 478 F. Supp. 2d 897, 904 (E.D. La. 2007). (footnote omitted)).

As a highly influential figure in the MDL world, single-handedly presiding over thirteen percent of all nationwide MDL cases from 2015 to 2019,129Ronald C. Porter, Lex Machina, Product Liability Litigation Report 10 (Rachel Bailey & Jason Maples eds., 2020). Judge Fallon’s decision in Vioxx to treat direct-filed cases as arising in the MDL court where they were directly filed could easily have shifted the treatment of all direct-filed cases, notwithstanding the other decisions that treated them differently.

In fact, Judge Fallon followed his 2007 decision with a 2008 law review article, in which he further advocates for the treatment of direct-filed cases as cases arising “in” the state of the MDL court:

A case filed directly into the MDL, whether by a citizen of the state in which the MDL sits or by a citizen of another jurisdiction, vests the transferee court with complete authority over every aspect of that case. This is because the transferee court is no longer cognizable as the transferee court under 28 U.S.C. § 1407, but is technically the forum court. Therefore, by filing cases directly into the MDL, plaintiffs, in effect, waive their Lexecon objections, thereby subjecting their cases to trial within the MDL.130Fallon et al., supra note 54, at 2356–57 (footnote omitted).

Judge Fallon is plainly correct that there is no procedural mechanism in the JPML rules or the codes of civil procedure that permits the direct filing of cases in an MDL court that could not otherwise entertain jurisdiction over the case. He resolves the issue by allowing direct filing in the MDLs under his management but then treating those cases as having been filed in Louisiana and thus arising under Louisiana state law. This makes intuitive sense, as for example a VioxxMDL case filed in the Eastern District of Louisiana, asserting state-law-based product liability claims, is clearly a diversity action that must be subject to the state laws of the state where the court sits. But it does not work in practice, as that case was filed by a non-Louisiana plaintiff against a non-Louisiana defendant and involved an injury occurring outside Louisiana such that, had the action been filed originally in a Louisiana state court, that court would have dismissed for lack of jurisdiction.