Introduction

The COVID-19 shutdowns highlighted the extraordinary scope of police powers that state governors and local officials can exercise and the lack of incentives to respect private property rights during emergencies. The states’ powers to impose large-scale shutdowns in the name of a public health emergency are well-established.1See Brian Angelo Lee, Emergency Takings, 114 Mich. L. Rev. 391, 399–400 (2015) (providing an overview of the contexts in which courts have recognized the emergency and public necessity doctrines for physical seizures and regulatory constraints on the use of property). But what state officials and judges broadly forgot in the process is that property rights place limits on the use of police powers to close businesses or strip them of economic viability without just compensation.2See Timothy M. Harris, The Coronavirus Pandemic Shutdown and Distributive Justice: Why Courts Should Refocus the Fifth Amendment Takings Analysis, 54 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 455, 457 (2021) (arguing that takings law is inadequate to compensate individuals and businesses impacted by COVID-19 shutdowns); see also Ilya Somin, Does the Takings Clause Require Compensation for Coronavirus Shutdowns?, Volokh Conspiracy (Mar. 20, 2020), https://perma.cc/XV6A-WYAA (arguing that while compensation for shutdowns is not likely to be legally required under the Takings Clause, there is a strong moral rationale for compensation).

The result has been an unbalanced equation. During the Trump presidency, state governors and local officials (especially in Democratic states and cities) stood to gain politically from exercising police powers in sweeping ways to show that they were leading the effort to slow down the spread of COVID-19.3See, e.g., Jack Brewster, 87% of the States that Reopened Voted for Trump in 2016, Forbes (May 5, 2020, 3:33 PM), https://perma.cc/B3K8-U4AX(discussing the stark partisan split in reopenings from shutdowns as 21 of the 24 states that reopened in May 2020 were states which voted for Trump, while Democratic-led states and cities remained shut down to mitigate the spread of the virus). At the same time, takings law offered little to no constraint in preventing supposedly “non-essential” business owners from bearing the costs of periodic state government-imposed shutdowns in the name of the greater good.4See, e.g., Friends of Danny DeVito v. Wolf, 227 A.3d 872, 877, 895–96 (Pa.), cert. denied, 141 S. Ct. 239 (2020)(holding that the shutdowns of non-life sustaining businesses were not takings of private property for public use); McCarthy v. Cuomo, No. 20-CV-2124, 2020 WL 3286530, at *5 (E.D.N.Y. June 18, 2020) (holding that the owner of a gentleman’s club was not denied all economically beneficial use of his property by COVID-19 shutdown orders because he had the option to continue food and drink operations via take-out or delivery services). The disconnect between the exercise of police powers and takings constraints has been even more stark because states and localities have imposed the burden of shutdowns, and largely left to the federal government the role of partly mitigating the impact of shutdowns through Paycheck Protection Program (“PPP”) loans and handouts.5See Harris, supra note 2, at 480–82.

State police powers form part of our forgotten federalism—the sphere of powers that are solely possessed by the states under our federal Constitution.6E.g., Jennifer Selin, How the Constitution’s Federalist Framework Is Being Tested by COVID-19, Brookings Inst. (June 8, 2020), https://perma.cc/4FNR-5DD5 (discussing how the pandemic responses have highlighted the role of state governments in addressing emergencies). The power to shut businesses down in the name of a public health emergency is clear.7See infra Section I.B (providing an overview of state police powers). However, the significance of the takings clause and in particular the just compensation provision is also clear as those clauses provide a check on federal and state encroachments on property rights.8See, e.g., Abraham Bell & Gideon Parchomovsky, Taking Compensation Private, 59 Stan. L. Rev. 871, 877–85 (2007) (making fairness-based, efficiency-based, and political-based justifications for takings compensation); Michael H. Schill, Intergovernmental Takings and Just Compensation: A Question of Federalism, 137 U. Pa. L. Rev. 829, 841–65 (1989) (making fairness and efficiency arguments for takings compensation); Christopher Serkin, Passive Takings: The State’s Affirmative Duty to Protect Property, 113 Mich. L. Rev. 345, 360–71 (2014) (making utilitarian-based and fairness-based justifications for takings compensation). The challenge is determining how these constitutional principles intersect (or ought to intersect) in the context of extraordinary government interventions.

The substantive due process Lochner v. New York9198 U.S. 45 (1905). era of courts broadly striking down regulations for encroaching on property rights is a distant memory as the administrative state’s role at both the federal and state level is virtually uncontested.10E.g., Robert Brauneis, “The Foundation of Our ‘Regulatory Takings’ Jurisprudence”: The Myth and Meaning of Justice Holmes’s Opinion in Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon, 106 Yale L.J. 613, 701 (1996) (arguing that Mahon recognized the limits of police powers and the need for regulatory takings compensation); Robert G. Dreher, Lingle’s Legacy: Untangling Substantive Due Process from Takings Doctrine, 30 Harv. Envtl. L. Rev. 371, 379–82 (2006) (discussing how the Supreme Court’s Lingle decision conclusively severed regulatory takings doctrine from due process analysis); William Michael Treanor, Jam for Justice Holmes: Reassessing the Significance of Mahon, 86 Geo. L.J. 813, 865–66 (1998) (discussing the role of substantive due process in the seminal Mahon case that recognized regulatory takings, but arguing that regulatory takings should be viewed separately from due process concerns following the end of the Lochner era). But the fact that federal and state governments have sweeping authority to regulate private property (especially in emergencies) does not mean that federal and state governments should not face takings compensation consequences for implementing regulations that deprive business owners of the use of their property.11Compare Kimball Laundry Co. v. United States, 338 U.S. 1, 3, 5–6 (1949) (holding that compensation may be due, including some measure of going-concern value when a laundry was temporarily appropriated), and United States v. Gen. Motors Corp., 323 U.S. 373, 380–83 (1945) (holding that compensation was due when property was temporarily appropriated as part of the war effort), with United States v. Cent. Eureka Mining Co., 357 U.S. 155, 169 (1958) (holding that government action closing a gold mine to appropriate labor was not a taking due in part to the exigencies of war), and United States v. Caltex (Phil.) Inc., 344 U.S. 149, 156 (1952) (holding that the private property destruction at issue during wartime did not trigger a compensable taking). The shutdowns were not as invasive as physical occupations of property by the state. But the economic effect of the prolonged loss of their livelihoods was nearly as sweeping for many businesses directly affected by the pandemic shutdowns and occupancy/operation restrictions.

This Article seeks to make the case for shutdown compensation within the existing framework of temporary, regulatory takings doctrines and raises both judicial and statutory reform proposals to expand the scope of economic liberty takings and other takings protections.12In an earlier work, I made the case for personal “liberty takings” to compensate pretrial detainees whose liberty is temporarily “taken” by the state yet are never ultimately convicted of a crime. See Jeffrey Manns, Liberty Takings: A Framework for Compensating Pretrial Detainees, 26 Cardozo L. Rev. 1947(2005). In this work, I explore the contours of “economic liberty takings” and seek to establish takings protections for businesses that face government-ordered shutdowns or other restrictions on their activities that strip businesses of their ability to function. Unlike many constitutional constructs that have been sheer creations of judges, takings protections are clearly enshrined in the texts of both federal and state constitutions.13U.S. Const. amend. V; e.g., Cal. Const. art. 1, § 19; see also Chi., Burlington & Quincy R.R. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U.S. 226, 241 (1897) (holding that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the Fifth Amendment’s just compensation requirement, thus making the takings clause binding on state governments). Numerous state constitutions expressly contain the just compensation requirement for takings. E.g., Cal. Const. art. 1, § 19(a); Conn. Const. art. 1, § 11; N.Y. Const. art. 1, § 7(a). But in practice, the contours of takings law have been almost exclusively crafted (if not stunted) by judges.14Timothy M. Mulvaney, Foreground Principles, 20 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 837, 840 (2013). I argue that the scope of temporary, regulatory takings doctrines lies in historical contexts unrelated to the sweeping economic impact of the COVID-19 shutdowns. The changed circumstances caused by the government-imposed shutdowns justify (1) revisiting these judicially constructed doctrines, and (2) considering both doctrinal reforms and statutory solutions that may shape governors’ use of their police powers.

Part I of this Article details the COVID-19 restrictions that occurred across the country. Part II then shows the limited potential for positioning economic liberty takings within the existing landscape of temporary, regulatory takings doctrines and explains how courts can build off existing doctrines to provide more expansive economic liberty takings protections. This expansion could occur by modifying the seminal Penn Central Transportation Co. v. New York City15438 U.S. 104 (1978). test for regulatory takings to place greater emphasis on the disruption of the investment-backed expectations of businesses and the economic fallout from regulations; relaxing the high bar Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency16535 U.S. 302 (2002). has set for temporary takings claims; and lowering the economic impact threshold for Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council17505 U.S. 1003 (1992). categorical takings. Part III shows the significance of these proposed reforms by highlighting the range of unsuccessful takings claims that occurred during the pandemic. Part IV makes the case for a complementary, statutory approach for claims that may not rise to the level of a temporary, regulatory taking by constructing a sliding scale of compensation based on the extent of the impact of regulations on businesses’ profitability. These proposals restore greater balance between the exercise of state police powers and the expectations of businesses, while preserving incentives for businesses to work within temporary, regulatory constraints to maintain their profitability.

Finally, this Article offers a balanced approach to compensating businesses for economic liberty takings by focusing on declines in net profits. Courts have traditionally struggled to translate the logic of real-property-based physical-takings compensation to the temporary, regulatory takings business context.18Daniel L. Siegel & Robert Meltz, Temporary Takings: Settled Principles and Unresolved Questions, 11 Vt. J. Envtl. L. 479, 512 (2010). The concern is that using business losses or revenue declines as metrics for takings compensation may fuel moral hazard as these numbers are hard to verify and easy to inflate and may disincentivize mitigating damages.19See Christopher Serkin, The Meaning of Value: Assessing Just Compensation for Regulatory Takings, 99 Nw. U. L. Rev. 677, 707, 735–36 (2005). My solution is to offset the expansion of economic liberty takings eligibility with a limited compensation focus on a business’s declines in profits. Federal and state corporate tax filings provide a baseline for a business’s net profits. Using the previous year’s net profits (or a multi-year average) as a baseline for potential takings compensation would facilitate ease of administration, reward the honesty of companies in complying with tax law, and serve as a cap on damages. This approach would also incentivize businesses to mitigate damages as the limited scope of profit-based compensation would induce businesses proactively to take cost-savings measures in the face of potential takings.

I. Framing the Pandemic Shutdown Problem

This Part describes the challenge of managing a government response to the COVID-19 pandemic while respecting takings principles. Section A briefly sets up the nature of the problem. Section B introduces the police power justifications for pandemic restrictions. Section C uses New York, California, and Florida as examples of various approaches state governments used. Lastly, Section D develops a taxonomy of business restrictions based on severity.

A. The Unique Nature of the Pandemic Threat

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed one of the greatest challenges to national and global public health in the past century.20See Alfred Lubrano, The World Has Suffered Through Other Deadly Pandemics. But the Response to Coronavirus Is Unprecedented, Phila. Inquirer (Mar. 22, 2020), https://perma.cc/CQB6-MYGJ. The high transmission rate of the virus, coupled with the global movement of goods and people, has made this virus particularly difficult to contain as it continues to mutate and spread both regionally and globally.21E.g., Benjamin Laker, 6 Challenges Leaders Will Face During the Coronavirus Crisis, Forbes (Mar. 16, 2020, 4:30 PM), https://perma.cc/2CUT-Y8XT; Lubrano, surpa note 20.

The uncertain nature and duration of the COVID-19 virus distinguishes it from other emergencies that our country has faced in years past. Emergencies such as terrorist attacks and natural disasters have clear beginnings and ends,22Cf. Jeffrey Manns, Insuring Against Terror?, 112 Yale L.J. 2509, 2515–16 (2003) (explaining the challenges of insuring for terrorism and natural disasters, thereby suggesting that the event has a discrete beginning and end for an insurance payout). while the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic is in constant flux as mutations arise. The foreseeable durations of more conventional emergencies help to justify temporary government-mandated interventions that shut down businesses and public life as well as the absence of compensation for this type of short-duration, emergency shutdowns. For example, the length and impact of a hurricane can be measured with relative precision based on experiences with past hurricanes and meteorological data.23Eva Lipiec & Peter Folger, Cong. Rsch. Serv., IF10719, Forecasting Hurricanes: Role of the National Hurricane Center (2019). Temporary government shutdowns to deal with this type of threat of finite duration fall within well-established emergency exemptions from takings and rarely arouse controversy.24See discussion infra Section II.E. For this reason, most people and businesses voluntarily comply and accept broad, time-limited sacrifices for the public good in the case of conventional emergencies. In contrast, the nature and duration of the COVID-19 pandemic were far from clear.

The extraordinary nature of the COVID-19 pandemic led to similarly extraordinary government action. Starting in March of 2020, state governors and local officials began imposing periodic shutdowns of categories of businesses that bureaucrats deemed “non-essential” in an effort to contain the spread of COVID-19.25Xue Zhang & Mildred E. Warner, COVID-19 Policy Differences Across U.S. States: Shutdowns, Reopening, and Mask Mandates, 17 Int’l J. Env’t Rsch. & Pub. Health, Dec. 18, 2020, at 1–2. For nearly a year, the scope of this burden remained unclear because of the open-ended duration of the threat. Many of the states that lifted these regulations imposed a “second wave” of partial shutdowns during the summer of 2020 after renewed spikes in COVID-19 numbers that lasted into February 2021.26E.g., Bobby Welber, Stricter Bar, Restaurant COVID-19 Rules Announced for New York, Hudson Valley Post (July 16, 2020), https://perma.cc/7DBU-7TPE.

The subsequent waves of regulatory shutdowns may be more financially problematic for many businesses than the first wave due to the weakened balance sheets from the initial shutdowns. The danger of mutations leading to further large-scale shutdowns and restrictions raises the need to consider enhanced judicial or statutory frameworks for compensating businesses adversely affected by these extraordinary government interventions.27Holly Yan, Why a 2nd Shutdown over Coronavirus Might Be Worse Than the 1st—And How to Prevent It, CNN (June 25, 2020, 8:50 AM), https://perma.cc/3ENE-MSMW.

As importantly, states and localities had divergent approaches in terms of the scope of shutdowns. This fact left business owners on opposite sides of a county or state line in very different economic circumstances.28Sarah Mervosh & Jasmine C. Lee, See Which States Are Reopening and Which Are Still Shut Down, N.Y. Times (Apr. 24, 2020), https://perma.cc/5HU9-LAGP (discussing the orders in place around the country as of April 24, 2020). The result was windfalls for “essential” businesses and e-commerce, but financial disaster for “non-essential” small and large brick-and-mortar firms who faced crippling restrictions on their businesses.29See Susan Selasky, Food Retailers See ‘Eye-Popping Profits’ During Pandemic. But Frontline Workers Get Crumbs, Chi. Trib. (Dec. 8, 2020, 8:26 AM), https://perma.cc/3VAF-GTLX. Crafting regulations that give windfalls to one group by shutting down competing businesses appears to fit the classic contours of takings law. But the challenge has been situating takings claims within the broad deference states enjoy in exercising police powers.

B. The Basis and Scope of State Police Powers

An irony of the COVID-19 pandemic is that the spread of the virus poses both a national and international threat, yet the response has been centered at the state (and local) level.30Zhang & Warner, supra note 25, at 1–2. This fact has triggered a revival of interest in federalism and a focus on police powers vested in states by the Constitution and the Tenth Amendment. For the past century, most times that a crisis has occurred, people have looked to the federal government to “solve” the problem or at least mitigate the fallout through large-scale, short-term interventions or infusions of cash.31See, e.g., Eamonn K. Moran, Wall Street Meets Main Street: Understanding the Financial Crisis, 13 N.C. Banking Inst. 5, 77–94 (2009) (discussing how Wall Street and Main Street relied on Uncle Sam’s large-scale interventions to mitigate the effects of the financial crisis). But the COVID-19 crisis was different because efforts to contain the spread of the virus had to occur at the state and local level where person-to-person transmission was occurring. The federal government generally does not have the authority to regulate intra-state activity unless the intra-state activity falls within the scope of an implied power of the Constitution or under the Taxing and Spending Clause.32U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1. Therefore, crisis management resulted in state governors (and to a lesser extent local officials) being thrown into the spotlight in crafting virus containment plans as the federal government could not act within its powers. As a result, state and locally crafted plans were often inconsistent with one another and led to businesses of the same type receiving different treatments.

The police powers of the states are derived from the Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution, which permits state governments to regulate and restrict property for the public health, safety, and general welfare of its citizens.33Id. art. VI, cl. 2. The Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reinforces this provision by granting the states all powers, which are not delegated to the federal government.34Id. amend. X (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”). The U.S. Supreme Court has held that police powers granted to the states extend to all matters “affecting the public health or the public morals”35Stone v. Mississippi, 101 U.S. 814, 818 (1880) (considering lotteries). and that “[t]he states traditionally have had great latitude under their police powers to legislate as ‘to the protection of the lives, limbs, health, comfort, and quiet of all persons.’”36Metro. Life Ins. Co. v. Massachusetts, 471 U.S. 724, 756 (1985) (quoting Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36, 62 (1873)) (considering employment).

“When [a] state faces a major public health threat,” such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the state’s police powers “are at a maximum.”37Legacy Church, Inc. v. Kunkel, 455 F. Supp. 3d 1100, 1146 (D.N.M. 2020). In Gibbons v. Ogden,3822 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824). the Supreme Court described state police powers as the ability to control “[i]nspection laws, quarantine laws, health laws of every description as well as laws for regulating the internal commerce of a State.”39Id. at 203 (holding that the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause included the power to regulate navigation). In Jacobson v. Massachusetts,40197 U.S. 11 (1905). the Supreme Court upheld the validity of a state law requiring vaccinations for smallpox.41Id. at 39 (holding that it could require adults fit for vaccination to receive the vaccine). Justice Harlan held that “although this court has refrained from any attempt to define the limits of [police powers], . . . it has distinctly recognized the authority of a State to enact quarantine laws and health laws of every description.”42Id. at 25 (internal quotation marks omitted). Courts have framed this holding as a two-pronged test which upholds “emergency public health measure[s] . . . unless (1) there is no real or substantial relation to public health, or (2) the measures are ‘beyond all question’ a ‘plain, palpable invasion of rights secured by fundamental law.’”43Cross Culture Christian Ctr. v. Newsom, 455 F. Supp. 3d 758, 766 (E.D. Cal. 2020) (quoting Jacobson, 197 U.S. at 31).

At the same time, Jacobson held that states cannot exercise police powers in “an arbitrary, unreasonable manner.”44Jacobson, 197 U.S. at 28. Embedded in every exercise of police power is the tension between protecting public welfare and respecting individual rights, and state officials have continuously struggled to balance these interests.45See Lawrence O. Gostin, The Future of Public Health Law, 12 Am. J.L. & Med. 461, 462–63 (1986). Police power is tempered by the need to respect religious liberty, private property, civil rights, and patient-privacy rights.46Jorge E. Galva, Christopher Atchison & Samuel Levey, Public Health Strategy and the Police Powers of the State, 120 Pub. Health Rep., 2005 Supp. 1, at 20, 21–24 (2005); see also Gostin, supra note 45, at 469–71 (discussing the ways in which compulsory state actions directed towards persons with infectious diseases are subject to higher levels of judicial scrutiny, especially when they interfere with fundamental liberties). However, outside of these basic limitations, states continue to assert broad police powers, especially in the wake of 9/11. Shortly after 9/11, the Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities drafted the Model State Emergency Health Powers Act (“MSEHPA”),47Ctr. for L. & the Pub.’s Health at Georgetown & Johns Hopkins Univ., Model State Emergency Health Powers Act: A Draft For Discussion (2001), https://perma.cc/J73L-L5AZ. legislation that seeks to codify and delineate the specific police powers that state governors possess, including the power to appropriate, control, decontaminate, condemn and destroy property in emergencies without compensation, and involuntarily quarantine people without notice.48Id. arts. V, VI. While many scholars at the time were eager to reshape the landscape of police powers and increase government authority in light of 9/11, other scholars and policy makers have been critical of MSEHPA, noting its overly broad grant of state authority, which lacks judicial oversight and infringes upon civil liberties. CompareGalva, supra note 46 at 24–26 (arguing that police powers should be redesigned to allow for greater levels of state authority in response to public health emergencies, while still respecting individual rights), and Warren Kaplan, Massachusetts Disease Control Law in the 21st Century: Running in Place?, 87 Mass. L. Rev. 84, 93–95 (2002)(discussing ways in which state police power may be utilized more swiftly in response to bioterrorism attacks post-9/11), with Fazal R. Khan, Ensuring Government Accountability During Public Health Emergencies, 4 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 319, 321–22 (2010) (arguing that “the gravest threat to civil liberties during a [public health emergency] stems from federal powers [created post-9/11], not putative state powers under the MSEHPA”). Forty states have incorporated MSEHPA in whole or part into state law, a point which recognizes most states’ broad embrace of police powers.49Joseph Mishel, The Model State Emergency Health Powers Act: Balancing Public Safety and Civil Liberties 6 (Oct. 10, 2019) (unpublished comment) (on file with Seton Hall University Law School Student Scholarship).

C. The Use of Police Powers to Shut Down and Restrict Businesses

States have leveraged emergency police powers to impose sweeping shutdown orders in an effort to contain the transmission of COVID-19. Most states have created different mandates and regulations for businesses that state governors deemed “essential” and “non-essential.” Essential businesses typically include public and private businesses, such as grocery stores, health care providers, utilities, banks, essential manufacturing, and gas stations.50See, e.g., N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.6 (Mar. 18, 2020), https://perma.cc/N59K-TERL (implementing “in-person restrictions” for all businesses except those which are deemed essential). “Non-essential” typically includes businesses and places of public accommodation geared towards recreation and entertainment, like gyms, theaters, salons, dine-in restaurants, sporting/concert venues, and shopping malls.51See id. (inferring that “essential” businesses create a category of “non-essential” businesses). “Essential” businesses have been allowed to remain fully or close to fully operational throughout the periodic shutdowns. “Non-essential” businesses have been affected to various degrees, sometimes having to completely cease operations, and at other times facing limits on occupancy or operations based on the extent of COVID-19 spread or the degree of intensive-care-unit-bed availability in the region.

To highlight the potential range of takings claims, the following discussion lays out the types of shutdown orders issued by state governors in California, New York, and Florida. California and New York are Democratic states that took the lead in championing COVID-19-related restrictions, while Florida serves as an example of the strikingly different approaches that Republican-led states took towards pandemic shutdowns.

1. New York

As the initial U.S. epicenter of COVID-19, New York implemented some of the most draconian executive orders that highlighted the tension between the use of police powers and potential takings. On March 16, 2020, Governor Andrew Cuomo issued Executive Order 202.3,52N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.3 (Mar. 16, 2020), https://perma.cc/SC8V-4T7X. ordering that gatherings and events of more than 500 people “be cancelled or postponed.”53Id. Restaurants and bars were to cease dine-in operations and offer take-out and delivery only.54Id. Video and casino gaming centers as well as gyms, fitness centers, and movie theaters were ordered to cease operations.55Id. On March 18, Governor Cuomo required places of “public amusement” to close completely and for shopping malls to close all indoor common areas to the public.56N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.5 (Mar. 18, 2020), https://perma.cc/HEP8-ZQKH. A similar order compelled businesses and organizations designated as “non-essential” to limit their in-person work force to 50% by March 20.57N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.6, supra note 50. Businesses deemed “essential,” such as supermarkets and big box stores with grocery sections, were exempted from in-person restrictions and benefited from the closure of competitors.58See id. Subsequent executive orders banned in-person work forces for non-essential businesses and expanded the scope of non-essential businesses to include barbershops and nail salons.59N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.7 (Mar. 19, 2020), https://perma.cc/LUV4-KA7J; see also N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.8 (Mar. 20, 2020), https://perma.cc/7ETK-ZN3W.

New York began easing the COVID restrictions in May 2020. On May 14, New York lifted in-person workforce restrictions for Phase One businesses in construction, agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting retail in certain geographic regions.60N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.31 (May 14, 2020), https://perma.cc/S9DY-XFAC. By May 29, Phase Two industries, like professional services, real estate, retail, and barbershops, were allowed to operate in-person.61N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.35 (May 29, 2020), https://perma.cc/MT23-RCDS. On June 12, Phase Three industries in eligible sectors, such as food services and personal care, were allowed in-person operations.62N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.41 (June 13, 2020), https://perma.cc/WC6Y-YUC8. On June 26, in-person restrictions were lifted for Phase Four industries like higher education, film and music production, and low-risk arts and entertainment, including professional sports games without fans.63N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.45 (June 26, 2020), https://perma.cc/J7GY-UYEP. Gatherings of fifty or fewer people were allowed as well.64Id. On July 10, malls were allowed to open at 25% capacity. When the second surge of COVID-19 began in the fall, New York first initiated “micro-cluster” shutdowns in neighborhoods of New York City, and from November 2020 through January 2021 reinstated many of the more draconian Phase I COVID restrictions, which were phased out in February 2021 as the contagion rate receded.

2. California

On March 19, 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom issued Executive Order N-33-20 directing all residents to stay home.65Cal. Exec. Order No. N-33-20 (Mar. 19, 2020), https://perma.cc/SXQ7-GCS4. The order exempted what the governor deemed to be “essential” critical infrastructure sectors, which encompassed thirteen sectors, ranging from health care to energy to critical manufacturing.66See Essential Workface, COVID19.CA.GOV (Sept. 22, 2021, 12:47 PM), https://perma.cc/QR34-XAT6 (noting the thirteen sectors of exempted workers); see also Guidance on the Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce: Ensuring Community and National Resilience in COVID-19 Response, Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Sec. Agency (Mar. 28, 2020) [hereinafter Guidance on the Essential Infrastructure Workforce], https://perma.cc/6U5S-9GBG. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency guidance is referenced by the California Executive Order N-33-20. See Cal. Exec. Order No. N-33-20, supra note 65. On May 7, Sonia Angell, the State Public Health Officer of the California Department of Public Health, issued SHO Order 5-7-2020,67Order of the State Public Health Officer (May 7, 2020), https://perma.cc/YWV3-SJ89. which outlined Stage 2 reopening procedures, with counties that showed progress being permitted to move through Stage 2 more quickly than the State as a whole.68Id.; see also Cal. Exec. Order N-60-20 (May 4, 2020), https://perma.cc/KYF3-YEKB (authorizing the phased reopening plans). Stage 2 included the limited capacity reopening of some “lower risk” workplaces such as retail, manufacturing, offices, outdoor museums, childcare, and some personal services with certain modifications and guidance.69Resilience Roadmap, COVID19.CA.GOV (June 4, 2020, 10:15 AM), https://perma.cc/PP2F-JPMM; see also Industry Guidance to Reduce Risk, COVID19.CA.GOV (July 1, 2020, 6:19 PM), https://perma.cc/8ZUU-P2AC. Some parts of the state entered into the Stage 3 reopening of “higher risk” workplaces, but this process ground to a halt first in July 2020 and then more comprehensively in November 2020, as California experienced surges in COVID-19 cases. The California Department of Public Health contains a watch list70County Data Monitoring, Cal. Dep’t Pub. Health, https://perma.cc/T24W-7FHE. of counties with coronavirus cases on the rise, and Governor Newsom announced on July 13, 2020, that virtually every major county in California had to close a range of businesses including gyms, movie theaters, salons, family entertainment centers, zoos, card rooms, and museums.71Dustin Gardiner, Erin Allday & Tatiana Sanchez, Newsom Orders All California Counties to Close Indoor Restaurants, Bars, S.F. Chron. (July 13, 2020, 8:55 PM), https://perma.cc/M59D-2MYM. Furthermore, all California restaurants and bars had to close indoor dining services.72Id.

These rules were relaxed in the fall of 2020 but in the face of an uptick in cases, Governor Newsom instituted a curfew for most of the populated parts of the state starting on November 21.73See Press Release, Off. of Governor Gavin Newsom, State Issues Limited Stay at Home Order to Slow Spread of COVID-19 (Nov. 19, 2020), https://perma.cc/3VKF-KUL2. That approach was escalated into a regional stay-at-home order that applied to virtually all of the state from December 5, 2020 through January 25, 2021, which prohibited private gatherings and reinstated widespread shutdowns and occupancy restrictions of businesses except for critical infrastructure and retail.74See Cal. Pub. Health Officer Order (Dec. 3, 2020), https://perma.cc/J2U7-6UQZ (tying widespread business closures in regions of California to intensive care unit bed availability); see also Blueprint for a Safer Economy, COVID19.CA.GOV (Jan. 25, 2021, 6:21 PM), https://perma.cc/59KL-6L46 (announcing end to regional stay at home order). In February 2021, California began a phased lifting of most of its shutdown restrictions.

3. Florida

Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis took a different approach to the shutdowns and initiated shutdown measures at a slower pace than other states. Starting on March 17, 2020, the Governor ordered restaurants to operate at 50% dine-in capacity, and bars and nightclubs to suspend the sale of alcoholic beverages within thirty days of the order.75Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-68 (Mar. 17, 2020), https://perma.cc/525Y-CMHK. Three days later, Governor DeSantis suspended the sale of alcohol on vendor premises, halted all dine-in operations at restaurants, and closed all gyms and fitness centers.76Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-71 (Mar. 20, 2020), https://perma.cc/MY25-E2NG. On April 1, Governor DeSantis issued Executive Order 20-91,77Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-91 (Apr. 1, 2020), https://perma.cc/U6BY-XNZY. ordering residents to stay home unless to obtain or provide essential services or conduct essential activities, referencing the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (“CISA”) guidance on essential workers.78Id.

On May 15, 2020, Executive Order 20-12379Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-123 (May 14, 2020), https://perma.cc/7RNY-4QWA. initiated Phase 1 of the state recovery plan, permitting restaurants to operate dine-in services at 50% capacity, and allowing in-store retail establishments, museums, libraries, and gyms to operate at up to 50% of building occupancy.80Id. Effective June 5, Governor DeSantis issued Executive Order 20-139,81Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-139 (June 3, 2020), https://perma.cc/ZW8L-AJJ7. announcing the transition to Phase 2 for all Florida counties except Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach. Phase 2 allowed for full outdoor dining capacity and 50% indoor dining capacity for restaurants and bars.82Id. Gyms, retail establishments, museums, and libraries could now operate at full capacity, and amusement parks could reopen subject to approval from the county. Organized youth activities and professional sports games could operate with caution as well. Concert venues and theaters were to remain at 50% capacity.83Id.; see also Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-123, supra note 79 (authorizing professional sports to resume training); Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-131 (May 22, 2020), https://perma.cc/CU88-Z67T (authorizing youth activities). By mid-summer, Florida lifted virtually all restrictions on the state level, while some localities retained occupancy limits on a range of “non-essential” businesses. In contrast to California and New York, Florida’s governor resisted the reinstatement of shutdowns during subsequent COVID surges during the fall of 2020 and instead relied on businesses implementing safeguards against transmission.84See Phillip Valys, Some South Florida Restaurants Close Dining Rooms to Wait out Coronavirus, S. Fla. Sun Sent. (July 2, 2020, 7:53 PM), https://perma.cc/X7GY-4Q94.

4. Essential v. Non-Essential Businesses

In all three of these states, clear distinctions were made between businesses that governors deemed “essential” and “non-essential.” With the exception of New York—which had its own framework—the other states broadly relied on the CISA guidance document, which delineates sixteen industry sectors that the federal government considers “essential critical infrastructure.”85See Guidance on the Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce, supra note 66. Combined with the Empire State Development’s guidance on the matter, “essential” businesses generally include:

| * health care operations; |

| * infrastructure (energy, water, waste, transportation, communications); |

| * infrastructure-related and life-sustaining manufacturing; |

| * life-sustaining retail (e.g., grocery stories, pharmacies, gas stations); |

| * financial services; |

| * defense; |

| * life-sustaining community services (e.g., homeless shelter, food banks); and |

| * infrastructure-related construction.86Guidance for Determining Whether a Business Enterprise Is Subject to a Workforce Reduction Under Recent Executive Orders, Empire State Dev. (June 29, 2020, 10:25 AM) [hereinafter Guidance Under Recent Executive Orders], https://perma.cc/4HM4-LL68; Guidance on the Essential Infrastructure Workforce, supra note 66. |

These essential businesses were allowed to operate at close to normal, if not full, capacities throughout the shutdowns.87Id.; see also Cal. Exec. Order No. N-33-20, supra note 65; Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-91, supra note 77.

In contrast, non-essential businesses were forced to close partially or fully and faced significant constraints amidst gradual reopenings.88See, e.g., Resilience Roadmap, supra note 69 (outlining California’s limited return to work after stay-at-home order). Looking at each state’s reopening plans reveals the types of businesses that were allowed to reopen first and each state’s stages for reopening (see Figure 1).89Each state created its own reopening plan. See Re-open Fla. Task Force, Plan for Florida’s Recovery: Safe. Smart. Step-by-Step. (2020), https://perma.cc/ZTH4-VJ95(Florida’s reopening plan); Reopening New York, N.Y. Forward, https://perma.cc/T4M6-YFNZ (New York’s reopening plan); Resilience Roadmap, supra note 69 (California’s reopening plan).

Figure 1: State-by-State Comparison of COVID-19 Reopenings

| Phase | New York | California | Florida |

| One | Construction, agriculture, fishing, and hunting retail | Preopening county COVID progress metrics | Restaurants, gyms, museums, barbershops, and retail at 50% |

| Two | Professional services, real estate, retail, and barbershops | Curbside retail, offices, outdoor museums, childcare, limited dining and personal services | Full outdoor dining and 50% indoor dining; theaters at 50%; and everything else at full capacity |

| Three | Food services and personal care | Hair & nail salons, gyms, movie theaters, sporting events | Everything at full capacity |

| Four | Schools, film and music, low-risk arts and entertainment (was partly implemented as of 2/2021 with 10% audiences allowed for entertainment events and partial school reopenings) | Concert venues, sporting events with live audience (was put on hold 2/2021) | N/A |

D. The Spectrum of Businesses Affected by the Shutdowns

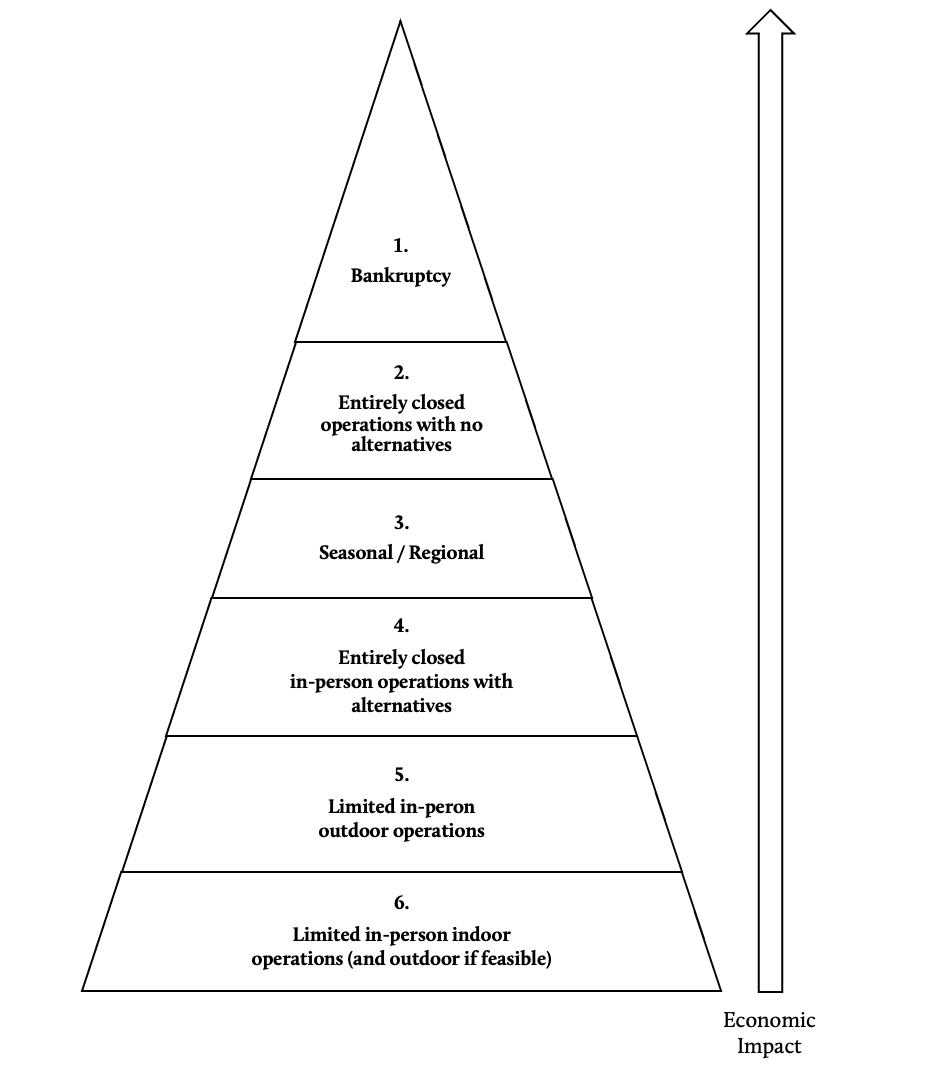

Businesses faced different treatment from state governments depending on the nature of the business and a range of economic consequences from the shutdowns. The impacts can be categorized across a spectrum based on the extent of shutdown restrictions, the availability of alternatives, and the economic toll. The following categorization in Figure 2 is not exhaustive yet provides examples of the types of business impacts that may fall along a potential takings’ spectrum.

Figure 2: COVID-19 Business Restrictions Based on Economic Impact

Category One businesses include those that have filed for bankruptcy as a result of the shutdowns, which may result in Chapter 11 reorganizations or Chapter 7 liquidations.90See generally Bankruptcy: What Happens When Public Companies Go Bankrupt, U.S. Sec. & Exch. Comm’n (Feb. 3, 2009), https://perma.cc/F6C7-28E9 (discussing the different avenues of corporate bankruptcy). Chapter 11 bankruptcy filings increased by 48% in May 2020 compared to May 2019, and from April to May alone, bankruptcy filings increased by 30%.91Pandemic Continues to Force Businesses to Explore Bankruptcy, Epiq Angle: Blog (July 1, 2020), https://perma.cc/KJ7W-8Q7G. Some of the sectors with the highest number of bankruptcy filings included restaurants, hospitality, entertainment, and retail, all of which faced shutdowns during the initial stages of the state responses.92Id. Examples of companies that have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy include: CMX, J.C. Penney, Neiman Marcus, Brooks Brothers, J.Crew, Muji, Apex Parks Group, California Resources, and Chesapeake Energy.93Peg Brickley & Kosaku Narioka, Pandemic Forces Japan’s Muji to Put U.S. Stores into Bankruptcy, Wall St. J. (July 10, 2020, 6:09 PM), https://perma.cc/6TAH-R3NV; Rebecca Elliott, Fracking Trailblazer Chesapeake Energy Files for Bankruptcy, Wall. St. J. (June 28, 2020, 6:01 PM), https://perma.cc/2C37-LKT3; Alexander Gladstone, California Resources, State’s Largest Driller, Files for Bankruptcy, Wall. St. J. (July 15, 2020, 10:33 PM), https://perma.cc/LJA2-MTHS; Suzanne Kapner & Andrew Scurria, J.C. Penney, Pinched by Coronavirus, Files for Bankruptcy, Wall. St. J. (May 15, 2020, 8:30 PM), https://perma.cc/8EXE-GXMJ;Becky Yerak, Amusement-Park Operator Apex Files for Bankruptcy, Wall. St. J. (Apr. 9, 2020, 3:26 PM), https://perma.cc/772U-EU7X; Retail Industry Turns to Bankruptcy Due to COVID-19, Epiq Angle: Blog (June 10, 2020), https://perma.cc/PG4D-AZDC; Pandemic Continues to Force Businesses to Explore Bankruptcy, supra note 91.

As businesses deal with the aftermath of periodic shutdowns in response to COVID-19 surges, experts expect the number of bankruptcy filings to continue increasing as economic consequences have lingered long after reopenings.94See Katy Stech Ferek, U.S. Business Bankruptcies Rose 48% in May, Wall. St. J. (June 4, 2020, 6:14 PM), https://perma.cc/C3BC-H4AR. While bankruptcy may lead to reorganizations rather than wind ups, the economic impact of bankruptcy represent one of the most clear examples of businesses (and their investors and employees) bearing the burden from shutdowns of select segments of the economy for the public good. Some of the affected businesses may have been teetering on the edge of bankruptcy prior to the shutdowns.95See, e.g., Kapner & Scurria, supra note 93(discussing J.C. Penney’s failure to adapt to e-commerce market prior to the pandemic). Others such as the bankrupt Garden Fresh Restaurants buffet chain may be market victims of COVID-19 as their business models may have foundered due to contagion concerns even in the absence of shutdowns.96Jonathan Maze, The Owner of Souplantation and Sweet Tomatoes Files for Chapter 7 Bankruptcy, Rest. Bus. (May 15, 2020), https://perma.cc/5NUF-XH69. But the case for economic liberty takings compensation may be at its peak in the context of bankruptcies induced by regulations.

Category Two businesses were prohibited from operating in-person, and during shutdowns have no alternative means of making revenue. This category includes businesses such as:

| * nail salons; |

| * barbershops; |

| * tattoo parlors; |

| * day care centers; |

| * theaters; |

| * malls/brick-and-mortar retail; |

| * casinos; |

| * smoke/bar lounges & nightclubs; |

| * zoos & museums; |

| * gyms; |

| * live arts; |

| * non-essential categories of manufacturing; |

| * recreational sports; and |

| * places of public amusement.97See, e.g., Scott Patterson, As Amusement Parks Reopen, Will Americans Ride Roller Coasters in a Pandemic?, Wall. St. J. (June 2, 2020, 5:30 AM), https://perma.cc/Z95V-8YAW (“We’re not a restaurant that can still do carryout. We went from being open to 100% shuttered.” (quoting an amusement park CFO)). |

The nature of the business models for these firms means they are effectively unable to generate any revenue under shutdowns, making them some of the strongest candidates for takings claims. For example, a barbershop or beauty salon could begin selling beauty supplies on the street outside of their business or attempt online sales.98See Margot Roosevelt, Will Small-Business Owners Go to Jail for Breaking Coronavirus Rules? We’ll Find out, L.A. Times (May 29, 2020, 11:01 AM), https://perma.cc/8MXV-AYGM (noting that street sales for one L.A. beauty salon could not cover shutdown loss, only half of previous sales). But the nature of their (typically) small scale and cost structure means that it would be difficult for these businesses to make this transition in a profitable way.99Id.

In a survey of over 600 beauty professionals, 96% of respondents said they became effectively unemployed for months due to the spring 2020 shutdowns.100Alena Maschke, ‘Many of Us Have Run Out of Money:’ With Reopening Months Away, the Beauty Industry Struggles to Survive, Long Beach Bus. J. (May 9, 2020), https://perma.cc/YHL9-QEDV. The top two industries that had the highest rates of government shutdowns in April 2020, when closure rates were the highest across all sectors, were (1) health and beauty, and (2) arts and entertainment, with 89% and 79% closures respectively.101Report: How Many Local Businesses Have Had to Close Due to COVID-19?, Womply, https://perma.cc/5MMU-WLYX (charting business closure rates by business category). With the average small business only holding a cash buffer of twenty-seven days, it is no surprise that these business sectors had the highest permanent closure rates during the pandemic.102See Diana Farrell & Chris Wheat, Cash is King: Flows, Balances, and Buffer Days: Evidence from 600,000 Small Businesses, JP Morgan Chase Inst. 14 (2016); see generally Ruth Simon, Amara Omeokwe & Gwynn Guilford, Small Businesses Brace for Prolonged Crisis, Short on Cash and Customers, Wall St. J. (July 22, 2020, 11:52 AM), https://perma.cc/7HJY-MZSZ.

Category Three businesses include seasonal and regional businesses in which the bulk of revenue is generated in a place or time of year that may be particularly exposed to a multi-month shutdown or occupancy/operations limits. Examples include:

| * tourism; |

| * hotels; |

| * recreation/amusement parks; |

| * summer camps & programs; and |

| * hunting & sport retail.103See, e.g., Charity L. Scott & Liam Pleven, Summer Businesses Fear Coronavirus Lockdowns Means a Lost Season, Wall St. J. (Apr. 18, 2020, 12:00 AM), https://perma.cc/EGR9-THDT. |

Because they often have low-margin, high-volume revenue models, businesses like amusement parks, ice cream parlors, restaurants, and tourism-related businesses are in jeopardy, if they are forced to shut down or operate at limited capacities.104See id. For these businesses, even being permitted to operate at limited capacity may not necessarily justify the costs of actually opening.105One restaurant owner exclaimed, “You can’t make money at 50% full. So, there’s a lot of challenges.” Id. For example, many amusement park companies earn the bulk of their income during the summer months due to both climate and school vacations facilitating family travel.106Id. (discussing how cold climate seasonal and regional businesses faced ruinous economic consequences from spring and summer shutdowns). States and regions that have major tourism industries experienced the seasonal effects of shutdowns even more.107See Kim Mackrael, Coronavirus Hits Hawaii’s Tourism-Dependent Workforce Hard, Wall St. J. (May 4, 2020, 5:30 AM), https://perma.cc/8HMP-UF3G (noting the importance of tourism in Hawaii’s economy). Hawaii’s shutdowns, for instance, are projected to lead to roughly 25% of its businesses closing permanently with impacts on restaurants, hotels, and other related businesses, such as shops and tour operators.108Id.; see also Fred Bever, Maine’s Seasonal Businesses Feeling Economic Effects of the Coronavirus, NPR (May 16, 2020, 7:01 AM), https://perma.cc/DN52-86BG (describing tourism communities in Maine facing similar crises despite low infection rates).

Businesses that are regionally based, such as those concentrated in downtown districts, tourism hotspots, and college towns, share parallel shutdown consequences with seasonal businesses.109E.g., Justin Baer, College Town Economies Suffer as Students Avoid Bars, Football Tailgating, Wall St. J. (Sept. 21, 2020, 7:00 AM), https://perma.cc/AZ6R-VJX7(discussing how Virginia Tech’s local economy continued to struggle after students returned due to social distancing preferences and precautions). Service sector businesses, such as law and accounting firms located in downtown areas, still flourished throughout the shutdowns because most employees could work from home.110E.g., Andrew Maloney, After Profits Soared in 2020, Firms optimistic About Revenue Uptick This Year, Am. Law. (Feb. 1, 2021, 4:39 PM), https://perma.cc/E4SK-K3G7 (noting that across 130 major firms net income was up 9.9% during the pandemic due to reduced discretionary and travel spending costs compared to 3.9% growth in 2019). But businesses that cater to downtown firms, such as restaurants, retail, and sundry shops, lost their customer bases due to the shutdowns and could not easily transplant their businesses elsewhere.111E.g., Jamie Goldberg, Downtown Portland Businesses, Derailed by Pandemic, Say Protests Present a New Challenge, Oregonian (Aug. 2, 2020, 8:39 AM), https://perma.cc/EC2Z-C6X9(discussing how one downtown Seattle pizzeria recalls daily sales as low as $18.75, attributing the losses to absent office workers and tourists). Most American downtowns had foot traffic plunge by 75% during the shutdowns from April 2020 through August 2020, and the hangover effect of shutdowns left downtown businesses facing economic challenges even after they were able to partly reopen.112E.g., id. (discussing how foot traffic in downtown Portland declined by over 75% during the summer of 2020); cf. Carmen Ang, Pandemic Recovery: Have North American Downtowns Bounced Back?, Visual Capitalist (Nov. 3, 2021), https://perma.cc/V53P-WRAF (comparing reductions in downtown office traffic across American metropolitan areas). For example, hotels in downtown Portland have seen an approximately 75% decline in occupancy after reopening compared to the prior year, and downtown stores faced similar revenue shortfalls because of continued restrictions on adjacent businesses.113Goldberg, supra note 111.

Category Four businesses include those that were forced to shut down in-person operations yet had alternative ways of making some revenue. Examples of these businesses include:

| * restaurants with take-out / fast food restaurants; |

| * online fitness classes; |

| * virtual arts and entertainment; |

| * retail with online business; and |

| * office-based professional services.114See, e.g., Jaewon Kang, Whole Foods CEO John Mackey Says Many People Are Done with Grocery Stores, Wall St. J. (Sept. 11, 2020, 10:06 AM), https://perma.cc/8EU4-5PB6 (noting how consumer spending habits have shifted online for purchasing groceries). |

The most fruitful example for this category would be sit-down restaurants once they were allowed to resume take-out operations. For retail, the types of businesses that would fall under this category would be those that operate both online and in-person. For most retail stores, online sales constitute only a small portion of their overall sales, and as a result, by July 15, 2020, only 69% of retailers had made their rent payment for the month.115Aisha Al-Muslim & Soma Biswas, Retail Carnage Deepens as Pandemic’s Impact Exceeds Forecasts, Wall St. J. (July 22, 2020, 5:30 AM), https://perma.cc/L4JG-R88P. Both the restaurant and retail industries suggest that even though alternative methods of sales are possible, they may not make up for the lost revenue from in-person sales due to the shutdowns.

Category Five includes businesses that were later allowed limited outdoor operations in May and June 2020, like restaurants, youth programs, recreational sports, and fitness classes. Towards the end of May, restaurants, many of which could now offer limited outdoor dining, were experiencing a 24–37% dip in daily revenue when compared to 2019.116Data Dashboard: How Coronavirus/COVID-19 Is Impacting Local Business Revenue Across the U.S., Womply [hereinafter Data Dashboard, Business Revenue], https://perma.cc/BXX6-4HYV (comparing multiple industries in each state: Average Revenue Last Week vs. Same Week In 2019). In terms of youth sports programs, an April 2020 poll conducted by the Aspen Institute’s Project Play initiative revealed that 38% of local sports leaders expected to lose up to 50% of their revenue over the next year.117Jay Cohen, Youth Sports Coalition Seeks Federal Aid Due to Coronavirus Pandemic, Associated Press (May 24, 2020), https://perma.cc/VH2T-56TK. Two-thirds of youth summer camps closed for the 2020 summer season.118Megan Leonhardt, Coronavirus Forced 62% of Summer Camps to Close This Year and Early Estimates Predict the Industry Will Take a $16 Billion Revenue Hit, Make It (July 3, 2020, 9:30 AM), https://perma.cc/LV72-VDBU. Around 27% of these closed camps offered some form of virtual camp, generating some revenue, but not enough to make up for normal earnings.119See id.

Category Six businesses include those that were later allowed indoor operations, usually at limited capacities of 25% to 50%. Many businesses like restaurants, barbershops, salons, casinos, and gyms fell into this category as states eased restrictions.120See, e.g., Fla. Exec. Order No. 20-139, supra note 81 (reopening bars and restaurants to 50% capacity). These changes resulted in the reversal of fortune for many businesses. For example, in June 2020, restaurants with outdoor or limited indoor dining experienced a 20% dip in daily revenue from a year earlier—a significant improvement from the 66% decrease back in late March 2020 when restaurants fell into Category Five of take-out and delivery only.121Data Dashboard, Business Revenue, supra note 116. Health and beauty businesses that were allowed to reopen earlier in 2020 enjoyed an increase in daily revenue due to pent-up demand.122Cf. Jeffry Bartash, U.S. Retail Sales Jump 7.5% in June, but Fresh Coronavirus Outbreak Poses New Hurdle, MarketWatch (July 16, 2020, 9:27 AM), https://perma.cc/3V54-KB6E (discussing the positive impact that pent-up consumer demand had on retail sales in June 2020). In contrast, when Maryland reopened its casinos at 50% capacity in June 2020, revenue had declined by 27% from the previous year.123Amy Kawata, Coronavirus Impact: Report Shows Significant Drop in Casino Revenue Despite Reopening, CBS Balt. (July 7, 2020, 3:54 PM), https://perma.cc/CJ6H-YFBB.

These are just examples of the kinds of businesses that may fall into each Category in Figure 2.124States have categorized businesses in various ways, but there are general similarities, such as the reopening of outdoor and indoor operations at limited capacities. See, e.g., Tom Wolf, Industry Operation Guidance, SCRIBD (May 28, 2020, 9:00 AM), https://perma.cc/7KXS-GEF2; Guidance Under Recent Executive Orders, supra note 86; What’s Closed Under the State or Local Health Orders?, Santa Clara Cnty. Pub. Health (July 17, 2020), https://perma.cc/8RF9-87E7. With each reopening phase, some of these businesses will shift down the spectrum as they are allowed to resume various levels of operations. Some businesses will also fall into multiple Categories based on the extent of restrictions for different parts of their operations.

II. An Overview of Existing Temporary, Regulatory Takings Law

This Part provides an overview of the existing temporary and regulatory takings doctrines. Section A lays out the tension between takings and the police power. Section B discusses the origins of regulatory takings. Section C outlines current takings doctrine, and Section D addresses some limitations of the doctrine when regulatory takings may not apply. Section E notes recognized exceptions to regulatory takings, such as emergency takings. Finally, Section F critiques the reluctance of courts to address the relationship between takings and state police power.

A. The Tension Between Police Powers and Takings Protections

While the efficacy of shutdowns in slowing down the spread of the virus has been a matter of public debate, courts have clearly established the legality of police power-based shutdowns.125See infra Section II.E. The question is whether state governments are obligated to compensate business owners for shutdowns that impose burdens on segments of the business world for the good of the many. The purpose of having shutdowns recognized as temporary, regulatory takings is not to question the exercise of state police powers, but rather to incentivize state governments to internalize some of the economic costs that shutdowns impose.126See, e.g., Roger Hanshaw, Paying for a Pandemic: “Just Compensation” and the Exercise of Police Powers for Public Safety, Nat. Res. & Env’t, Winter 2021, at 38, 39–40. That way government actors will have reasons to develop a more thoughtful approach to shutdowns (and future exogenous shocks requiring state intervention) that minimizes the economic impact.

State governors have effectively imposed unfunded mandates on businesses.127See, e.g., N.Y. Exec. Order No. 202.6, supra note 50; Cal. Exec. Order No. N-33-20, supra note 65. State legislatures have been largely powerless to temper the shutdowns, and the affected businesses have been left with no substantive legal recourse.128This has lead states like Pennsylvania to pass constitutional amendments through referendum to allow legislatures to limit their governor’s use of emergency powers. See Marc Levy & Michael Rubinkam, Pennsylvania Voters Impose New Limits on Governor’s Powers, Associated Press (May 19, 2021), https://perma.cc/T6SQ-GT9Z. Governors simply face no meaningful oversight or accountability for these exercises of their police powers except for the distant prospect of future elections. The hope is that once shutdowns are recognized as economic liberty takings, states will be forced to internalize the economic consequences of shutdowns. This accountability will foster more carefully tailored uses of police power during the pandemic and future emergency situations that recognize the need for state action but also respect private property rights.

B. The Origins of Regulatory Takings

Under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment, the government may take private property “for public use” through a regulation or through the exercise of eminent domain, so long as it pays “just compensation.”129U.S. Const. amend. V. Similar takings provision exist in state constitutions. E.g., Cal. Const. art. 1, § 19(a); Conn. Const. art. 1, § 11; N.Y. Const. art. 1, § 7(a). The just compensation requirement seeks to prevent the government from forcing select groups from bearing burdens for the public good.130See Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419, 435–36 (1982); Armstrong v. United States, 364 U.S. 40, 49 (1960). Regulatory takings temper state police powers by mandating just compensation if a regulation goes “too far” in restricting property rights.131See Pa. Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 U.S. 393, 415 (1922). “The basic understanding of the Fifth Amendment makes clear that it is designed not to limit the government interference with property rights per se, but rather to secure compensation in the event of otherwise proper interference amounting to a taking.”132First Eng. Evangelical Lutheran Church v. Cnty. of Los Angeles, 482 U.S. 304, 315 (1987) (emphasis omitted). Therefore, properly framed takings claims in response to shutdowns would not allege that a state exceeded police powers, but rather that the state needs to internalize the costs of shutting down economic activity by paying just compensation to affected businesses.

Broad deference to state executive power may be needed in emergencies, but there must be a point at which the exercise of executive power triggers a temporary, regulatory taking and just compensation for affected property owners. Most state governors (and mayors) enjoy four-year terms and in the case of governors, enjoy virtually unfettered authority in exercising police powers.133See, e.g., Md. Code Ann., Pub. Safety § 14-3A-02 (West 2021); N.J. Stat. Ann. § 38A:3-6.1 (West 2021); N.Y. Exec. Law § 28 (McKinney 2021). This fact means governors are exercising emergency police powers without any accountability from the legislature, and accountability to the people in the form of reelection is often a distant prospect years away.134The notable exception is California Governor Gavin Newsom who faced a recall election, largely driven by a backlash to the state’s COVID response. See Sarah Abruzzese, Gavin Newsom and the Coronavirus-Driven Recall Effort, U.S. News & World Rep. (Feb. 19, 2021), https://perma.cc/AXN2-EYE2. The takings doctrine is designed to ensure balance occurs in the exercise of police powers for public purposes by incentivizing state governors (and local officials) to factor the costs of their actions into how they structure government interventions.135Under physical takings, the government must go to court to seize the property at issue; while under regulatory takings, the government is free to issue regulation and the affected property-owner must go to court to claim the takings. Frederic Bloom & Christopher Serkin, Suing Courts, 79 U. Chi. L. Rev. 553, 605 (2012) (“[I]nverse-condemnation actions amount to a kind of eminent domain proceeding in reverse; . . . they ask if property has been taken and the government should thus be forced to pay.”).

Courts have often conflated the question of the permissible scope of state police powers with the issue of regulatory takings compensation.136See, e.g., Mahon, 260 U.S. at 401–02; Mugler v. Kansas, 123 U.S. 623, 668–69 (1887). In 1887, the Supreme Court in Mugler v. Kansas,137123 U.S. 623 (1887). held that a statute which prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcohol did not constitute a compensable taking because the legislation was a valid exercise of state police power enacted for health and safety purposes.138Id. at 661, 668–69, 671. The court distinguished an exercise of state police power from a taking, explaining that the former seeks to abate a public nuisance, while the latter takes property away completely and involves a physical taking of property.139Id. at 669. This distinction was problematic in restricting takings to physical appropriations of property.140See Shai Stern, Taking Emergencies Seriously, 51 Urb. Law. 1, 13–15 (2021).

Pennsylvania Coal Co. v. Mahon141260 U.S. 393 (1922). corrected this problem by introducing the concept of regulatory takings. The Supreme Court recognized a regulatory taking in a case in which a state regulation barred an owner from mining his own mineral claim, the government’s justification being to protect others’ surface-level buildings.142Id. at 414–15. “[W]hile property may be regulated to a certain extent [under a valid exercise of state police powers], if regulation goes too far it will be recognized as a taking.”143Id. at 415. Two factors should be considered when determining if a regulation goes too far: (1) the extent of the diminution of the property value, and (2) the public interest underpinning the regulation.144See id. at 413–14.

After Mahon, the focus in regulatory takings has been on whether the extent of property value reduction triggers just compensation.145See, e.g., Tahoe-Sierra Pres. Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Reg’l Plan. Agency, 535 U.S. 302, 326 (2002). Four years later, the Supreme Court in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co.146272 U.S. 365 (1926).signaled how high the bar would be for regulatory takings when the introduction of a zoning ordinance that diminished property values by 75% was not recognized as a taking.147Id. at 384, 397. The ensuing century of regulatory takings cases have continued to set a high threshold for takings claims, even as the reach of the administrative state has dramatically expanded.148See, e.g., Murr v. Wisconsin, 137 S. Ct. 1933, 1949–50 (2017).

C. Current Regulatory Takings Doctrine

Regulatory takings have evolved over time into three judicially constructed categories: permanent physical intrusions, total per se takings, and the catch-all, ad hoc balancing test for partial takings.149See Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419, 426–27, 433–34 (1982). Most regulatory takings regulations are analyzed under the ad hoc balancing test for partial takings established by Penn Central.150Penn Cent. Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978). But courts first look to see whether the regulation is governed by one of the two categorical takings categories: (1) a forced, permanent, and physical appropriation of property, or (2) a regulation that deprives a property of all economically viable uses.151See, e.g., Cedar Point Nursery v. Hassid, 141 S. Ct. 2063, 2071–72 (2021). Courts have generally not regarded temporary takings as falling within either of these two categorical takings categories and analyzed temporary takings claims under the partial takings Penn Central test.152See id. at 2072.

1. Categorical Takings

The two types of categorical takings are (a) permanent, physical appropriations of property, and (b) regulations that deprive property of all economically viable uses.

a. Permanent, Physical Appropriation or Intrusion

Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp.,153458 U.S. 419 (1982). established that a forced, permanent, and physical appropriation of property is a categorical taking.154See id. at 426. In Loretto, the Supreme Court held that a state law that authorized cable companies to install cables on property without the property owner’s consent are takings “without regard to the public interest that it may serve.”155Id. at 424–26. A challenge in analyzing this categorical takings category is determining what constitutes a permanent physical intrusion. Following Loretto, “permanent” was framed as meaning continuous as opposed to temporary and limited.156The Court clarified this notion of fixed by distinguishing Loretto from Kaiser Aetna v. United States and Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins, the latter involving physical invasions that were temporary and limited in nature, and hence not a permanent total taking. See Pruneyard, 447 U.S. 74, 83 (1980) (concluding that the California Constitution’s protection of free speech and petition was not a taking against private shopping center owners when those rights were exercised on shopping center grounds); Kaiser Aetna, 444 U.S. 164, 180 (1979) (holding that the Hawaiian government’s navigational servitude requiring petitioners to grant public access to a previously private pond was a compensable taking). However, this definition became muddled after the Supreme Court’s decision in Nollan v. California Coastal Commission,157See 483 U.S. 825 (1987). in which the Supreme Court held that a state imposition of a beach access easement on a landowner’s property constituted a permanent physical occupation requiring compensation.158Id. at 832, 841–42 (holding the California Coastal Commission’s permit grant, which was conditioned on appellants’ allowance of an easement along their beach for public use, was a permanent, physical taking). Nollan blurred the line between permanent and temporary physical invasions. Nollan also led lower courts to develop inconsistent definitions of “permanent,” with some defining it to mean a “substantial” burden on property and others focusing on the idea of a “fixed” burden on property owners.159See Lynn E. Blais, The Total Takings Myth, 86 Fordham L. Rev. 47, 69–71 (2017) (arguing that the total takings doctrine, which includes physical invasions, is incoherent in a way that makes it difficult for lower courts to apply). This “shadow Loretto doctrine” from the lower courts highlights the potential elasticity of the Loretto doctrine in addressing regulatory burdens on property.160Id. at 68–69. While Loretto and Nollan raise questions about the scope of regulatory burdens, the Lucas categorical takings test and Penn Central test for partial takings matter far more for understanding temporary, regulatory takings.

b. Deprivation of All Economically Viable Uses

The second category of per se categorical takings consists of regulations that deprive property owners of all economically viable uses of their property. Lucas established that a regulation is a compensable taking if it “denies all economically beneficial or productive use of land.”161Id. at 1015; see also id. at 1031–32 (holding that a South Carolina statute which prohibited Lucas from building any habitable structures on his land was a categorical compensable taking). The Court equated a regulation that deprives a property owner of all economically viable uses of their property to a “physical appropriation,” which should be treated like a permanent physical invasion.162Id. at 1017–18. In Lucas, the purchaser of coastal property lots faced a regulation that barred development on the land, which effectively denied all economically viable uses of the land.163Id. at 1008–09. While this categorical taking opens the door to regulatory takings claims, the Supreme Court to date has had a mixed record in how broadly to interpret this categorical taking. On the one hand in Palazzolo v. Rhode Island,164Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 U.S. 606 (2001). the Supreme Court found that a regulation that leads to a 94% reduction in property value does not amount to aLucas categorical taking.165Id. at 615–16, 631. But on the other hand, the Court expanded on Lucas in Horne v. Department of Agriculture,166576 U.S. 351 (2015). by holding that the physical appropriation of personalproperty—in that case, a marketing order requiring raisin growers to give a percentage of their crops to the federal government—constituted a per se taking.167Id. at 355–58, 370.

Rather than reducing the complexity and volume of litigation, both Lucas and Horne represent bright-line rules that are ill-defined around the edges and have resulted in little success for plaintiffs.168See Blais, supra note 159, at 82–85. Multiple studies have shown that after Lucas, the number of takings claims decreased and have experienced little success in federal and state courts. See, e.g., James E. Krier & Stewart E. Sterk, An Empirical Study of Implicit Takings, 58 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 35, 60 (2016) (finding that for total takings cases from 1979 to 2012, the success rate of such claims dropped from 64.3% to 25.8% after the Lucas ruling in 1992); Stewart E. Sterk, The Federalist Dimension of Regulatory Takings Jurisprudence, 114 Yale L.J. 203, 232 (2004) (explaining that even with per se takings issues, the Court provides relatively little guidance to lower courts since Lucas requires courts to take into account background principles of property law, which vary by state). The limited applicability of Lucas bright-line rules raises the significance of the third category of regulatory takings, which utilizes a multi-factor balancing test.169See Blais, supra note 159, at 84–86, 88.

2. Partial Takings and the Penn Central Balancing Test

If a regulatory takings claim does not meet the criteria for a categorical taking, then it falls under the third category of partial takings, established by Penn Central.170Penn Cent. Transp. Co. v. New York City, 438 U.S. 104, 124 (1978); see also Serkin, supra note 8, at 350–51. In Penn Central, New York City passed a historic preservation ordinance that prohibited Penn Central from building a tower over Grand Central Station.171See Penn Cent., 438 U.S. at 112–18. Penn Central argued that this ordinance was a taking because it substantially reduced the economic value of their property and unfairly singled them out with a unique burden in the name of the public interest.172Id. at 119. In rejecting Penn Central’s claims, the Supreme Court applied a multi-factor balancing test for determining whether a government regulation constitutes a taking.173Id. at 124. The Penn Central test requires courts to assess: (1) the character of the government action, (2) the regulation’s economic effect on the landowner, and (3) the extent to which the regulation interferes with the landowner’s reasonable investment-backed expectations.174Id.

a. The Character of the Government Action

The first prong of Penn Central holds that regulations are more likely to be treated as a taking if they constitute a forced and permanent physical invasion of property, the taking of a core property right, or if the property owner in question is unfairly burdened relative to others.175See id. at 124–25. In contrast, courts are less likely to find a takings claim if the purpose of the regulation is to protect the community or if there is an average reciprocity of advantage (i.e., the burden in one regulatory context is offset by other burdens facing other parties).176See id. at 124–26.Penn Central itself serves as a cautionary tale in how far courts will go in deferring to government action. The Supreme Court held that Penn Central was not unfairly singled out because over 200 buildings were also restricted by the ordinance (in a city of one million structures), which weighed in favor of denying a taking.177Penn Cent., 438 U.S. at 131–32, 134.

b. The Economic Impact of the Regulation

The second prong of Penn Central holds that regulations are more likely to be takings if they destroy most or all economically viable uses of property that are not justified by a strong public interest.178Id. at 127–28. Regulations are likely not a taking if they leave the owner with viable economic use of their property or a reasonable return on their investments.179Lucas v. S.C. Coastal Council, 505 U.S. 1003, 1016–18, 1016 n.7 (1992). In Penn Central, the Supreme Court found that because the ordinance prohibited additional construction on Penn Central’s property, the regulation did not affect the present value or use of the property as a train station.180Penn Cent., 438 U.S. at 135–36.

Courts have often been leery of finding regulatory takings because of the difficulties of quantifying the economic impact of regulations.181Murr v. Wisconsin, 137 S. Ct. 1933, 1943 (2017) (listing the economic impact as one of the “complex” factors to consider in assessing regulatory takings). The concern is that non-regulated industries do not have set rates of return on their capital that can serve as benchmarks of economic impact and instead require case by case analysis of the impact of regulation on a given business.182See id. at 1949–50 (holding that “the ultimate question [of] whether a regulation has gone too far . . . cannot be solved by any simple test”). Thus, courts traditionally look to evidence of business losses or revenue declines due to regulations.183See, e.g., Rose Acre Farms, Inc. v. United States, 373 F.3d 1177, 1185 (Fed. Cir. 2004). The challenges of applying these lenses for compensation is that they may fuel moral hazard as these numbers are hard to verify and easy to inflate and may disincentivize business efforts to mitigate damages. While the economic impact of regulations may be clear, courts may be reluctant to open up the doors to a pandora’s box of regulatory takings compensation calculations.

What is clear is that a high degree of economic impact is required in order to establish a regulatory taking. As the Supreme Court in Lingle v. Chevron U.S.A. Inc.184544 U.S. 528 (2005). framed the issue, the economic impact from regulations must be so severe that it is “functionally equivalent” to a direct appropriation.185Id. at 539. The U.S. Court of Federal Claims, which handles most takings claims against the federal government and repeatedly utilizes the comparable sales approach, generally looks for a diminution of value “well in excess of 85 percent.”186William C. Means, Jr., The Economic Value of Conserved Land: Examining Whether Conservation Easements Represent a Sufficient Source of Land Value to Influence the Outcome of Regulatory Takings Claims, 69 Ohio St. L.J. 743, 773 (2008) (quoting Walcek v. United States, 49 Fed. Cl. 248, 271 (2001)).

c. The Interference “[W]ith [D]istinct [I]nvestment [B]acked [E]xpectations”