Introduction

In recent years, income inequality and antitrust enforcement have been repeatedly linked in popular and policy discussions. Particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic shocked and dramatically reshaped daily lives across the world, concerns regarding economic inequality have surged.1See, e.g., Carmen Sanchez Cumming, Raksha Kopparam & Maryam Janani-Flores, The Economic State of the Union in 2022, Presented in 11 Charts, and What Policymakers Can Do to Make the Recovery More Equitable and Resilient, Wash. Ctr. Equitable Growth (March 1, 2022), https://perma.cc/T3ZS-CQEQ. Simultaneously, as the pandemic increased global reliance upon technological tools—already the topic of significant debate regarding appropriate antitrust enforcement—and catalyzed disruptions along all manner of supply chains, created various shortages, and drove price increases, the appropriate role of antitrust laws once again reemerged as a critical topic of discussion. It was perhaps inevitable that the two phenomena would be linked in policy discussions.

Indeed, the nature of a causal link between income or wealth inequality and antitrust is longstanding, though surprisingly underexamined. Since early in the twentieth century, the U.S. Government sought to examine the supposed “intimate relation” between income distribution and monopoly power.2Temp. Nat’l Econ. Comm., 76th Cong., Investigation of Concentration of Economic Power 1 (Comm. Print 1940) [hereinafter TNEC Concentration]. In the decades since, this intimate relation has been invoked repeatedly.

Today, again, arguments that antitrust enforcement might affect the distribution of income and wealth have reemerged. Literature examining the income distribution in the U.S. over the last century or so has demonstrated that since at least 1980, the distribution of income has become increasingly skewed. The “college premium”—“that is, the relative wage of college versus high-school educated workers”3Daron Acemoglu & David Autor, Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings 7 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 16082, 2010),

https://perma.cc/D4QY-J938..—has grown in recent decades, as have the share of income flowing to the top 1%, job polarization, and wage polarization.4Ramaa Vasudevan, The Rise of the Global Corporation and the Polarization of the Managerial Class in the U.S., 29 Rev. of Pol. Econ. 539, 539 (2017). The trend, then, has been toward an increasingly unequal income distribution.

At the same time, antitrust enforcement embraced and implemented the consumer welfare standard. This standard judges alleged violations of the antitrust law by one key metric: how the conduct affects consumer welfare. Critics of this standard contend that it has impaired the power of antitrust enforcers in undesirable ways; that it has caused a decrease in antitrust enforcement rigor.5A. Douglas Melamed, Antitrust Law and Its Critics, 83 Antitrust L.J. 269, 271–74 (2020). Some further argue that this decline in antitrust enforcement is contributing to inequality trends and concerns.6Id. at 280–82. And ramping up antitrust enforcement could help to reverse them.7Id. at 274–75.

Despite how vocal these arguments have become, the question of whether or how much increased antitrust enforcement might affect the distribution of income, or might impact recent observed trends, seems comparatively underexplored.

Regardless of how one evaluates the existence or a particular level of inequality, it is instructive to investigate any trend of increasing income inequality—especially when that trend leads to an increasingly polarized job market, with more extremes and a smaller center, and when there was never an explicit intent to create such a trend. During this time period, there has been much debate over how to generate more wealth across the economy—for example, what policies and approaches best spur growth—but not a specific desire to create more wealth for the top of the income distribution while simultaneously reducing wealth for the lower distributions.

For a functioning, healthy free market system to survive, there are many reasons to be wary of extreme levels of inequality.8Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality ix–xxiv (2012). Over several decades we might expect to see fluctuations in inequality, likely increasing and decreasing at different time periods. But a steady trend toward inequality, with no meaningful trend away from it, should provoke serious conversations regarding what is—and what is not—driving that trend. And, potentially, when the causes of that trend are better understood, as to how to reverse or slow it. We do indeed see many of these conversations happening today.

Both phenomena—rising income inequality and diminishing antitrust enforcement—are complex and nuanced. Properly understanding them and navigating a viable path forward demands a deeper understanding of the landscape of each and the interplay between the two. Antitrust commentaries to date fail to grapple with the specifics of what is happening in the income inequality space and how the two alleged trends might be related or reinforcing.

The goal of this Article is to understand better the capacity of antitrust law and policy to affect inequality trends and to begin the work of ascertaining its role in contributing to recent income inequality trends. It is generally agreed that individual antitrust cases have distributional effects. But the causal link between antitrust enforcement and inequality, writ large, remains underdeveloped and underexplored. There is a robust literature exploring trends in income distribution which would seem to provide ample ground for developing the relationship between inequality trends and antitrust enforcement.

Before diving into the analysis, there is a relevant distinction: antitrust’s role in affecting trends on personal income versus individual consumption. Antitrust might be relevant on the income side, in terms of correcting market failures that would put more capital into the hands of those in the mid to lower portions of the income distribution. Consider, for instance, if employers hold monopsony power and are paying anticompetitive wages and antitrust enforcement is able to correct that behavior.

Antitrust might also be relevant on the consumption side—in terms of making goods and services more affordable or accessible to those on the lower half of income the distribution. Antitrust’s consumer welfare standard aims to make “consumers” as a broad category better off. But it tends not to ask whether, when those consumers are better off, precisely how those benefits are distributed across consumers—whether to wealthier or less wealthy, equally or disproportionately in one direction or another. Equality effects, specifically, are a consequence about which antitrust has historically been agnostic. As will be explored, there are important scenarios in which benefits have important progressive effects. Thus, there is a question of whether steps can be deliberately taken to achieve progressive benefits and whether doing so can have an impact on the inequality trends we are observing.

This Article uses income inequality as a particular focus for several reasons. Income distribution is especially well-explored and scrupulously analyzed, meaning there is a particular story to follow and potential insights to glean that might be relevant from an antitrust perspective. Moreover, income is, for most people, a critical component of economic wellbeing and a contributor to consumption capacity.

There are three primary theories as to how monopoly power and concentration might be contributing to inequality trends. First, the monopoly overcharges story, perhaps the most direct storyline. Here, a reduction in output or increase in price harms consumers. Such a reduction in output or increase in price is allegedly more harmful to lower-income consumers, who are more sensitive to such fluctuations, and thereby contributes to wealth gap. Second, the shareholder returns story. Beneficiaries of monopoly overcharges tend to be those who are disproportionately higher-income, thereby contributing to wealth inequality. Third, the employer monopsony power story. Here, powerful employers can offer lower wages, and that these wages disproportionately affect those of lower income distribution.

These theories raise questions relating to issues such as the distribution of monopoly overcharges and rents across the economy and income distribution, and whether employer-side power has changed in recent years such that they might be deploying their market power in ways that contribute to observed trends. This Article considers these questions and more.

Part I summarizes the income inequality literature, to provide a more detailed basis upon which to analyze the potential effect of antitrust enforcement across the period examined. Part II describes general antitrust law and enforcement trends since 1890, setting the stage for a comparison of the trends in antitrust and those observed in income distribution. Part III explores the connection between these trends. Part IV deploys these insights to consider the redistributive power of antitrust law. The work is a first step toward a richer understanding of how antitrust law and policy might contribute to income inequality trends and, ultimately, of whether changes in law, policy, or priorities might better facilitate desired goals.

I. Income Inequality Trends

Over the last several decades, empirical work on income inequality has contributed to our understanding of existing trends and potential causes. Various factors, including technological developments, globalization, and societal and political rules and norms have been explored, and seem likely to have contributed in different magnitudes over time. But as Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz noted, there is also “a growing consensus among economists that it is hard to parse out cleanly and precisely the roles of different forces.”9Id. at 80; see also Anthony B. Atkinson, Thomas Piketty & Emmanuel Saez, Top Incomes in the Long Run of History, 49 J. Econ. Lit. 3, 56 (2011) (“[E]xplanations are likely to be multivariate and we are confronted with the task of seeking to separate different influences.”). Some have suggested that doing so might, largely, be unnecessary at this point.10Stiglitz, supra note 8, at 80 (“To me, much of this debate is beside the point.”).

But certainly, some amount of understanding of the roles different forces play is important when it comes adopting (or not adopting) specific policy and legal actions. Such efforts require identifying areas most likely to achieve the ends desired, and thus are worthy of focus. Tradeoffs will inevitably need to be made. We would be best served to begin from an informed position.

As this Section develops, there has been considerable work documenting income inequality trends and attempting to distill causes. This Article argues, however, that one comparatively underdeveloped area is the impact of antitrust law and policy—what role it has played and what is its capacity to affect inequality (on a broad scale or on income inequality more specifically). While the literature to date reveals several factors that have contributed significantly (see below), the literature has yet to reveal the role of antitrust.

The debate regarding what is occurring, broadly, to drive inequality and how best to characterize the trends or their consequences, is largely outside the scope of this Article. The goal here is to compile foundational evidence relating to income inequality in one place, with a particular focus on the work that has been done with the highest potential relevance for antitrust policy.

A. Introduction to Early Income Inequality Literature and Findings

Today, one takes for granted the wealth of research into the existence, causes, and consequences of earnings inequality. The last few decades have witnessed an explosion of literature in this field. As Levy and Murnane noted in 1992, “within a decade, earnings inequality grew from a lightly studied branch of labor economics to a major research area.”11Frank Levy & Richard J. Murnane, U.S. Earnings Levels and Earnings Inequality: A Review of Recent Trends and Proposed Explanations, 30 J. Econ. Lit. 1333, 1334 (1992). They credit two particular observations with catalyzing this change: (1) diminishing middle class jobs, and (2) an increasing “skills mismatch” in the economy.12Id. at 1334–35. Scholars continue to explore these themes to this day.

The data reveal changing levels of income inequality and the share going to the top earners, both increasing and decreasing through most of the twentieth century.13Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, The Rise of Income and Wealth Inequality in America: Evidence from Distributional Macroeconomic Accounts, 34 J. Econ. Persps. 3, 10 (2020). As Goldin and Margo put it, the wage structure was on a “long-run roller coaster ride” from the 1940s through the late 1980s.14Claudia Goldin & Robert A. Margo, The Great Compression: The Wage Structure in the United States at Mid-Century, 107 Q.J. Econ. 1, 3 (1992) (“The wage structure . . . has been on a long-run roller coaster ride since 1940—with inequality falling precipitously during the 1940s, rising slightly in the 1950s and 1960s, and finally increasing sharply from the 1970s.”). Over the last few decades, however, the income inequality levels have been trending (fairly consistently) in an upward direction.15Saez & Zucman, supra note 13. The key findings from the literature conclude that: income inequality has increased fairly continuously since at least the 1980s (rapidly and then more slowly); this increase is not being driven by gender or racial factors; rather, it is primarily driven by trends among the top 1%, and even the top 0.1%, which is consistent with how these top earners affect longer term trends; and the “college premium” has increased significantly in recent years. A key result observed today is polarization in the workforce, both in terms of earnings and in terms of occupations.

The “beginning” in terms of research into U.S. income inequality trends is typically around 1913, which marks the start of the modern income tax era. Significant literature and popular discussion today focus upon the very top earners—the top 10 or even 1%. Even early studies of inequality focused upon the top decile due to historical limitations (prior to 1944 changes, only a small percentage had to file tax returns).

A report of the Temporary National Economic Committee (“TNEC”) published in 1940 represents one of the earliest publications addressing the concentration of income in the U.S.16See TNEC Concentration, supra note 2. That report examined the period between 1918 and 1937 and concluded that income inequality was lowest in 1920 and 1932 and highest in 1928 and 1929, with “no significant trend over the period as a whole.”17Id. at 16–17. The TNEC examined concentration of income for the highest 2% of earners (all that the data permitted), and divided that further into smaller and smaller subsets down to the highest 0.01%, five in total.18Id. at 16–23. The report noted that trends in the earlier and later years were very similar: the average total share of income received by the top 1% of earners was roughly 13% in the years 1918 to 1924 and in the years 1934 to 1937.19Id. Meanwhile, this share peaked in 1928 to 1929, at about 19%.20Id.

The report further found that the shares going to top earners declined more during periods of business depression and increased more during periods of business prosperity than the shares received by the more inclusive groups.21Id. at 35–36. This latter point—whether the very top income earners are more (or less) impacted by economy-wide experiences—will reemerge in later periods, as well. But the general consensus for this particular time period is that inequality trends were driven primarily (if not exclusively) by the country’s economic fate: with inequality increasing during economic boom years and decreasing during economic down years and war years.

The TNEC Report was commissioned to address “the intimate relation of the distribution of income to monopoly and the effectiveness of competition in general.”22TNEC Concentration, supra note 2, at 1. On the issue of monopoly and income trends, the report argued that “[i]t may be confidently stated that were it not for past and present monopoly in one form or other, the prevailing distribution of income would be considerably more equal.”23Id. at 2. In particular, it credited:

Rising land values; poorly organized markets; control of natural resources such as oil, copper, aluminum, and timber or of important stages in their fabrication; railroad development; strategic positions in the Nation’s financial markets; promotions of consolidations in industry; monopolistic practices and conditions in industries such as steel and tobacco; and the rapid expansion of new industries such as agricultural machinery, electrical appliances, motion pictures, chemicals, and radio—all these situations provided the basis for many of the large fortunes and in all of them strong elements of monopoly are found.24Id. at 1.

The report also concluded that incomes stemming from monopolistic conduct yield financial power used to further consolidate industry control and, “[i]n this way, the relationship between the concentration of income and industrial monopoly has tended to be interacting and cumulative.”25Id. Many of the arguments made today regarding income inequality and antitrust echo this same sentiment.26Note that because the data analyzed relate to top incomes, the report necessarily focuses upon the alleged relationship between those top incomes and monopoly concerns..

The report cautioned that, “[t]his is not to say that increasing the effectiveness of competition would yield equal incomes for all.”27Id. at 2. Rather, a “considerable degree of income inequality seems to be consistent with a high degree of competition and is probably an essential characteristic of a competitive economy.”28Id. at 2. Thus, the TNEC argued in favor of reducing monopoly practices to increase competition and income equality—but acknowledged that both monopoly and competitive outcomes are consistent with income inequality, perhaps even a significant amount. This important point is one with which the literature continues to struggle today. In discerning the distinctions between competition and monopoly, or between desirable and undesirable, market situations. While some situations fall clearly into one category or another, many others do not. And as this proposition makes clear, the distinction is important—both to how income inequality should be understood and to how, if at all, it should be addressed.

The notable income distribution event that followed this early period of stability29See Thomas Piketty & Emmanuel Saez, Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998, 118 Q.J. Econ. 1, 25 (2003) (“Top wage shares show a striking stability from 1927 to 1940.”). has been coined the Great Compression.30Goldin & Margo, supra note 14. This designation describes the period in the 1940s during which the wage structure narrowed considerably, and quickly. It also marks a period during which income inequality in the U.S. remained meaningfully below the levels seen in the preceding decades or those which followed—a period sometimes referred to as the Golden Age for income inequality.31Levy and Murnane, for instance, draw a parallel to Angus Maddison’s description of this period as the postwar “golden age” for productivity, arguing that the “onset of the Great Depression caused a break in trend as earnings inequality entered its own ‘golden age.’” Levy & Murnane, supra note 11, at 1340.

Goldin and Margo examined this period in depth to explore what was happening to wages and what was driving these changes. They note the wage structure narrowed significantly between 1940 and 1950, then began widening from 1950 to 1987 (the last year for which they had data).32Goldin & Margo, supra note 14, at 3, 8. They find that compression occurred in both the upper and the lower tails—perhaps explaining why the drop in inequality was so significant.33Id. at 27 (“The main finding is that wage compression in the upper range of the distribution (measured by the difference in the log of the wage at the ninetieth and fiftieth deciles) occurred during the war and continued long after wage controls ended, a finding from the clerical data as well (see Table VII). Compression in the lower portion of the distribution (from the tenth decile to the median) was generally strong in the prewar to war period but less strong in the war to postwar period, despite the continued rise of the minimum wage.”).

They identify several factors as likely motivators. While inequality was narrowing in the 1930s, this narrowing was far more modest and, they posit, driven largely by the minimum wages set by the National Industrial Recovery Act (“NIRA”).34Id. at 16. Their findings imply that “factors unique to the World War II period [] explain much of the initial compression.”35Id. This included governmental wartime policies, like the National War Labor Board (“NWLB”).36Id. at 23–28. The war likely also contributed to an increased demand for less-skilled manufacturing labor—although the data indicates this demand increased from the 1940s through the early 1960s, well after the war had ended.37Id. at 28 (“The upper tail of the distribution, even in relatively high wage and nonwar related industries, also narrowed considerably during the war. This fact, in combination with the relative stability in the wage structure from 1949 to 1959, bolsters the notion that market forces increased the demand for less-skilled manufacturing workers on a continuing basis from the 1940s to the early 1960s and served to keep in place a wage structure that was initially necessitated by the wartime economy and mandated by the command economy.”).

During this time, the college premium dropped significantly: between 1940 and 1950 the premium to college over high school graduation experienced a thirteen percentage point decline.38Goldin & Margo, supra note 14, at 6–8. It began rising again during the 1950s; but remained below the 1940 level in 1960.39Id. at 8. Meanwhile, supply of college-educated workers increased significantly heading into the 1950s, as many veterans took advantage of the GI Bill provision for college attendance.40Id. at 30–31. While demand for educated workers was increasing into the 1960s, it took some time for the college premium to rebound.41Id. at 29 (“[W]age compression in the 1940s between the lesser and more educated groups is, perhaps, no mystery. Relative demand stayed virtually constant, while relative supply increased. In the 1950s the supply of college-educated workers continued to increase faster than that of less-educated workers, while the growth in the relative demand for the more educated greatly exceeded that for the less educated. These demand effects continued into the 1960s, and the wage compression of the 1940s eventually began to unravel.”).

Goldin and Margo conclude:

The Great Compression, as we have called it, was primarily the result of a particular confluence of short-run events affecting the demand for labor and of institutional changes brought about by the war and the command economy that accompanied it. . . . compression was observed at the industry level during the period from the mid-1940s to the early 1950s, and compression occurred in both the upper and lower tails of the distribution.42Id.at 32.

This compression period is critical to the income inequality story. It marks a period of rapid, striking reduction in income inequality not observed before or since.43See, e.g., Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 33 (“The pattern of top shares over the century is striking: most of the decline from 1927 to 1960 took place during the four years of World War II. The extent of that decline is large, especially for very high wages.”); Levy & Murnane, supra note 11, at 1340 (“By the early 1950s, the trend of rapidly declining inequality had ended and the economy began a period of almost three decades in which inequality rose slightly.”). Income inequality remained fairly stable for the next few decades, then began climbing.

B. Recent Trends: The Increasing College Premium and Wage and Job Polarization

Since the Great Compression, much has changed.

One notable change is the college premium, or “the relative wage of college versus high-school educated workers.”44Acemoglu & Autor, supra note 3, at . The college premium had decreased during the 1940s before beginning to rise again in the 1950s, as noted above. Data following the college premium into the 2000s further reveals that the college premium dipped again during the 1970s. By the end of the 1970s, the premium was about where it had been in 1964. The college premium then began a consistent upward trajectory for the next several decades.45Id. at 7, fig. 1. By 2008, it had reached a “high water mark,” of sixty-eight log points, implying “that earnings of the average college graduate in 2008 exceeded those of the average high school graduate by 97 percent.”46Id. at 7.

The reversal of the college premium trend is largely attributable to a deceleration of relative supply, which has never entirely recovered. A confluence of factors caused this.47Id. at 8. The Vietnam War increased college attendance through the 1960s and 1970s artificially, as males could defer military service—and thus the draft—by enrolling. The comparatively larger Baby Boomer generation meant that enrollment was especially high, at a time when female enrollment also began to increase. When the war ended, however, enrollment dropped dramatically, particularly among males. The decreasing college premium in 1970s likely also contributed to this drop, as the drop in relative earnings likely rendered college less desirable.48Id. Recall the college premium is different from the return to college, so a drop in the college premium might very well mean that deferring working for several years and investing in additional education made less economic sense or was otherwise less feasible.

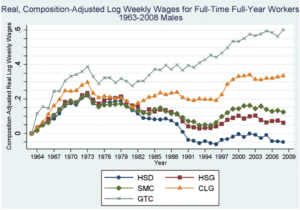

At the same time, changes were emerging in real wages across different education levels. Acemoglu and Autor first presented a breakdown of composition adjusted log weekly wages for full time, full year workers from 1963 through 2008, broken down into five education levels: (1) high school dropout (“HSD”); (2) high school graduate (“HSG”); (3) some college (“SMC”); (4) college graduate (“CLG”); and (5) greater than college (“GTC”).49Id. at figs. 4a & 4b. This graph reveals that the 1973 oil shock impacted all earners—with wage levels experiencing a quick drop, then stagnation, which they note was fairly consistent across genders and education groups. After the stagnation period, a period of increasing inequality across education groups began. This deviation was particularly striking among males, as shown in their graph reprinted below:

Figure 1:50Acemoglu & Autor, supra note 3, at fig. 4a (“Source: March CPS data for earnings years 1963-2008. . . . The real log wage for each education group is the weighted average of the relevant composition adjusted cells using a fixed set of weights equal to the average employment share of each group.”). Acemoglu and Autor also provide a graph for females, with the same breakdown through this period. While the early trends are the same, the disparity across education levels by the end of the sample is less pronounced among females, and all female educational levels saw real wage increases, albeit very modest ones for the lowest educational levels. Id. at fig. 4b.

Acemoglu and Autor focus on three variables regarding earnings evolution that had not previously been uncovered. First, much of the increase in the “college premium” in recent decades in fact derives from increased compensation to the “greater than college” cohort, that is, those with graduate level work. Second, a “major proximate cause of the growing college/high school earnings gap is not steeply rising college wages but rapidly declining wages for the less educated—especially less educated males.”51Id. at 10. They note that it is possible this is somewhat misleading, given it presents only wages and not other compensation, some of which has increased over the period, such as healthcare and leave (like vacation, parental, and sick time); though they expect increases in other compensation are unlikely to entirely offset their findings.52Id. at 10–11. Third, the gaps between some college, high school graduate, and high school dropout workers grew in the 1980s but apparently stabilized thereafter.

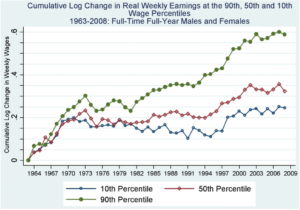

Acemoglu and Autor also tracked the evolution of real log weekly wages for full time, full year workers at the 10th, 50th, and 90th percentiles of the income earnings distribution from 1963 to 2008. This presentation again reveals a drop and stagnation into the 1980s. While the 90th percentile begins increasing the distance between the 10th and 50th in the 1970s, the meaningful separation occurs in later periods (as the college premium likewise grows).

Figure 2:53Id. at fig. 7a (“Source: March CPS data for earnings years 1963-2008. For each year, the 10th, median and 90thpercentiles of log weekly wages are calculated for full-time, full-year workers.”).

The Acemoglu and Autor work tracks and identifies the wage polarization occurring over the last several decades. Those with higher educational and income levels saw their real wages rise (and this rise occurred at a faster pace) while, at the same time, those with lower educational and income levels experienced real wage stagnation or even decreases.

A study by Song et al. tracks U.S. firms between 1978 and 2012, constructing a matched employer-employee data set, to demonstrate that “virtually all of the rise in earnings dispersion between workers is accounted for by increasing dispersion in average wages paid by the employers of these individuals.”54Jae Song, David J. Price, Faith Guvenen, Nicholas Bloom & Till von Wachter, Firming Up Inequality 1 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 21199, May 2015), https://perma.cc/C6ED-LV9W. This study finds “pay differences within employers have remained virtually unchanged, a finding that is robust across industries, geographical regions, and firm size groups.”55Id. The authors conclude that “this fact of stable inequality within firms should inform our understanding of the great increase in inequality within the United States over the last three decades.”56Id. at 30.

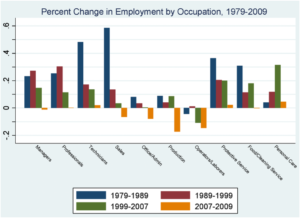

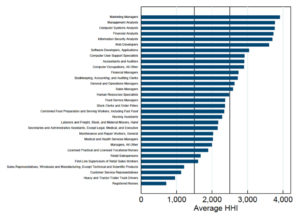

In addition to the increasing college premium and wage polarization, the literature also reveals “job polarization,” or “the simultaneous growth of the share of employment in high-skill, high-wage occupations and low-skill, low-wage occupations.”57Acemoglu & Autor, supra note 3, at 16 (emphasis omitted). This phenomenon has contributed to concerns about the declining middle class in America.58Id. at 68; see Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik & Rakesh Kochhar, Trends in Income and Wealth Inequality, Pew Rsch. Ctr. (Jan. 9, 2020), https://perma.cc/6PZ3-3VCM. Job polarization increasingly pushes workers toward either end of the education-wage spectrum, offering fewer options in the center space.59Acemoglu & Autor, supra note 3, at 22, 26. Note, the literature sometimes refers to “skill” level as, essentially, a proxy for education. This Article prefers to use the “education” level nomenclature, as this more accurately describes the phenomenon. For instance, a chef or artisan may be very highly skilled but not hold any college degrees. See id.

Acemoglu and Autor study this trend and present a graph depicting growth across ten broad occupation categories from 1979 to 2009.60Id. at fig. 12. They note that these ten occupational categories fit neatly into three groups. From left to right in the graph below, these are: First, highly educated, highly paid occupations, comprised of managers, professionals, and technicians. Between twenty-five and sixty percent of workers in these categories held at least a four-year college degree in 1979. Second, middle-educated, middle-paid occupations, comprised of sales, office and administrative support, production (including craft and repair), and operators and laborers (including fabricators). And third, service occupations, which the Census Bureau defines as jobs that entail helping or caring for others. Most workers in these categories have no post-secondary education and their hourly wages are lower than those of the other seven categories, on average.61Id. at 17–19, fig. 12.

Figure 13a demonstrates that occupations in the first and third categories saw growth across, essentially, the entire period studied. In fact, nearly all the decreases in employment are clustered within the occupations at the center of the graph—that is, the “middle” education/pay occupations. Most striking is the effect of the 2008 Recession, represented by the fourth bar in each of the four-bar clusters in the figure below. During this difficult economic period, the highly educated, highly paid occupations saw no absolute decline in employment. And the service occupations saw modestly positive employment growth (faring better than the highly educated, highly paid occupations). The middle-sector occupations were clearly the hardest hit: these occupations saw absolute declines in employment between seven and seventeen percent.62Id. at 18, figs. 12 & 13a.

Figure 3:63Id. at fig. 12 (“May/ORG CPA files for earnings years 1979-2009. The data include all persons ages 16-64 who reported having worked last year, excluding those employed by the military and in agricultural occupations. Occupations are first converted from their respective scheme into 326 occupation groups consistent over the given time period. All non-military, non-agriculture occupations are assigned to one of ten broad occupations presented in the figure.”).

Research to understand this phenomenon—why workers are being increasingly funneled away from traditionally middle-class roles—reveals the importance of the distinction between routine and nonroutine tasks in the modern economy.64Id. at 20–22. This research breaks occupations into categories based upon whether they are comprised mainly of cognitive or noncognitive and routine or nonroutine tasks. By and large, routine tasks (be it cognitive or noncognitive) dominate the middle-class jobs experiencing the largest employment declines. Meanwhile, the higher and lower end occupations tend to revolve around nonroutine cognitive or noncognitive tasks.

Two observations regarding how technological developments affect these occupations differently lead to the proposition that technology has a skill-bias effect in the modern economy, known as skill-biased technical change.65See, e.g., David H. Autor, Frank Levy & Richard J. Murnane, The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration, 118 Q.J. Econ.1279, 1279 (2003) (“A wealth of quantitative and case-study documents a striking correlation between the adoption of computer-based technologies and the increased use of college-educated labor within detailed industries, within firms, and across plants within industries. This robust correlation is frequently interpreted as evidence of skill-biased technical change.”); Giovanni L. Violante, Skill-Biased Technical Change, in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics 1–6 (Steven Durlauf & Lawrence Blume eds., Palgrave Macmillan 2d ed. 2008) (“Skill-biased Technical Change is a shift in the production technology that favors skilled over unskilled labor by increasing its relative productivity and, therefore, its relative demand.”); Colin Caines, Florian Hoffmann & Gueorgui Kambourov, Complex-Task Biased Technological Change and the Labor Market, 25 Rev. Econ. Dynamics 298 (2017). First, routine tasks—those which can (fairly) easily be broken down into a discrete set of repeating instructions—are more susceptible to substitution from technologies. Consider assembly lines or software programs (like Excel). Second, and relatedly, certain nonroutine cognitive tasks are complemented by technology. Consider legal research that previously required manually searching hard copies of legal precedent; advances to move case opinions to searchable digital databases have not necessarily made lawyers obsolete, but made them more efficient, and so more valuable.66Autor et al., supra note 65, at 1280 (“The simple observations that undergird our analysis are (1) that computer capital substitutes for workers in carrying out a limited and well-defined set of cognitive and manual activities, those that can be accomplished by following explicit rules (what we term ‘routine tasks’); and (2) that computer capital complements workers in carrying out problem-solving and complex communication activities (‘nonroutine’ tasks).”).

Moreover, as technology further supplements routine tasks, the importance of social skills in the workplace grows. Research demonstrates this characteristic has an impact distinct from skill level, and that workers are increasingly rewarded for demonstrating higher levels of social aptitude.67David J. Deming, The Growing Importance of Social Skills in the Labor Market, 132 Q.J. Econ. 1593, 1625 (2017) (“This shows that relatively higher returns to skill in social skill-intensive occupations are not simply a proxy for job complexity or overall skill requirements. . . . I find that the labor input of routine tasks has continued to decline, and that nonroutine analytical (math) task inputs stopped growing and even declined modestly after 2000. However, social skill task inputs grew by 24% from 1980 to 2012, compared to only about 11% for nonroutine analytical tasks. Moreover, while nonroutine analytical task inputs have declined since 2000, social skills task inputs held steady (growing by about 2%) through the 20000s. Not surprisingly, the decline in routine tasks mirrors the growing importance of social skills between 1980 and 2012.”). This has likewise affected the labor force, changing the composition of roles and the characteristics employers demand.68See John Maynard Keynes, Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren, in Essays in Persuasion (1932) (“We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come—namely, technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour. But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment. All this means in the long run that mankind is solving its economic problem.”).

C. Top Income Earners

Much of the recent research and scholarship has focused upon fluctuations in the share of earnings going to top earners—particularly within the ninetieth and ninety-ninth percentiles.69See Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 11–12. Those at the very top of the income distribution have tended to have an outsized impact upon income distribution for as long as there is data tracking it. The data reveal insights regarding how top earnings shares have fluctuated over the decades, the kinds of events that have most impacted these shares, and who these top earners are.

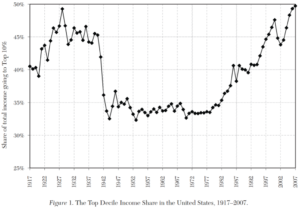

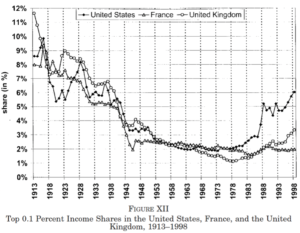

Piketty and Saez’s influential 2003 article first compiled a homogenous series of shares of total income for upper fractiles covering most of the twentieth century.70Id. at 2. Their research demonstrates changes in both the shares going to the top decile of earners and the composition of income—each of which is relevant to the antitrust inquiry.

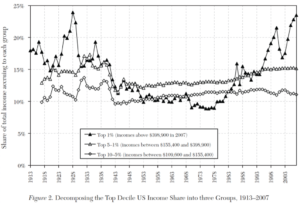

First, they measure how the share of income captured by the top decile has changed over time. As shown below in their Figure 1,71This graph updates Piketty and Saez’s original from the 2003 paper to include data through 2007. Atkinson et. al, supra note 9, at 6 fig. 1. the share hovered within the forty percent range for most of the 1920s and 1930s, before dropping precipitously in the early 1940s. The share then remained in the thirty percent range until the 1970s, when it began increasing again. Piketty and Saez note, in particular, that “the evidence suggests that the twentieth century decline in inequality took place in a very specific and brief time interval.”72Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 11. Similar to Goldin and Margo, they further posit that this “highly specific timing . . . strongly suggests that shocks to capital owners between 1914 and 1945 (depression and wars) played a key role” in the striking drop observed in the early period.73Id. at 12.

Figure 4:74Atkinson et al., supra note 9, at 6 fig. 1.

Piketty and Saez further break down the top decile into three components: the top 10–5% (P90–95), the top 5–1% (P95–99), and the top 1% (P99–100). This breakdown reveals that the top one percent “underwent enormous fluctuations over the twentieth century.”75Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 12. The top 0.01%, for instance, experienced “huge fluctuations”: from earning 400 times the average in 1915, down to 50 times the average in 1970, and back up 250 times the average by 1998.76Id.at 13. This breakdown suggests that the very top percentile of earners has an outsized impact. This revelation seems consistent with the TNEC Report’s early observation that examining smaller and higher fractions of earners among the top two percent showed more fluctuation with market events among the higher, smaller brackets.

Figure 5:77Atkinson et al., supra note 9, at 7 fig. 2.

Second, Piketty and Saez find the “income composition pattern has changed drastically between 1929 and 1998.”78Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 17. Earlier in the century, the top earners were “overwhelmingly rentiers deriving most of their income from wealth holdings (mainly in the form of dividends).”79Id. But by the end of the century, even the very top earners’ incomes derived in large part from wage and entrepreneurial income.80See id. at 15 tbl. III. Notably, they conclude the secular decline in capital is “entirely due to dividends.”81Id. at 19. Shares of interest, rent and royalties remained largely stable during the period examined, while the dividend share began around forty percent in the 1920s, and plummeted to less than ten percent by the 1990s.82Id.; see also Atkinson et al., supra note 9, at 7 fig. 2. This decline in capital income was critical to the reduction of top income shares before 1950.83Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 31. Those in the highest echelons were most sensitive to these capital reductions, as Figure 2 evidences.84See Atkinson et al, supra note 9, at 5 (“[T]he fall in the top percentile share is primarily a capital income phenomenon: top income shares fall because of a reduction in top wealth concentration.”).

As a result of these phenomena—increasing income share among top percentile earners in recent years, and an increasing portion of income derived from wages—top earners have been capturing a higher share of wage income in recent decades, as well. Piketty and Saez find that “wage inequality, measured by top fractile wage shares, starts to increase in the early 1970s.”85Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 31.

Wages continue to play a larger role in top incomes than it did prior to World War II. Indeed, a study by Bakija, Cole, and Heim demonstrates that salary and business income accounts for approximately 63% of the increase in the share of national income captured by the top 0.1% of earners between 1971–1980 and 2001–2010.86Jon Bakija, Adam Cole & Bradley T. Heim, Jobs and Income Growth of Top Earners and the Causes of Changing Income Inequality: Evidence from U.S. Tax Return Data 2–3 (Apr. 2012) (unpublished manuscript). These authors conclude that “theories to explain the rising top income shares . . . must largely be about compensation for labor.”87Id. at 3. The next subsection explores this notion further. Note, however, data also indicate that capital incomes have increased significantly for top earners in recent years.88See, e.g., Atkinson et al., supra note 9, at 53. Thus, it seems that capital incomes may also be intertwined in a particular way with recently observed trends.

Finally, the trends among the top earners continue to impact disparately those in the very highest percentiles. In recent years, the increases in income shares among top earners have been captured almost entirely by the top one percent, with modest or no gains flowing to the remaining nine percent.89See, e.g., id. at 7 fig. 2.

The literature also tracks the occupations comprising the top tier of earners. Here again, there are observed changes to which occupations command the top positions within this space. Before turning to a more comprehensive review of top income earners, it first might be interesting to trace the occupations of billionaires, alone, throughout the twentieth century. Delong’s analysis begins in the early 1900s, approximately the “peak of the relative frequency of billionaires.”90J. Bradford DeLong, Robber Barons: Honest Broker/Hoisted from 1998, Grasping Reality, (Jan. 1, 1998), https://perma.cc/R8X5-JTES. In 1900, most billionaires’ fortunes derived from railroads: of the twenty-two billionaires at the time, nine were related to railroad construction and operation, while five were related to finance, which at the time, “meant almost exclusively railroad finance.”91Id. By 1918, however, the industries producing billionaires had begun to diversify, and included photography, retail, chemicals, tobacco, farm equipment, automobiles, food processing, oil, and steel.

Into the mid–twentieth century, the number of billionaires grew more slowly, led primarily by aluminum and oil. From 1980 until nearly the close of the century, this growth has increased, adding new prominent categories. For the first time, a significant portion of billionaire fortunes were inherited, owing largely to the stock market boom at the end of the century. And a new “leading sector” DeLong describes as potentially comparable to the railroads of yore would combine electronics, software, entertainment, and telecommunications fortunes, accounting for a quarter or more of billionaires’ fortunes in 1996.92Id. This narrow focus upon the industries in which billionaires’ fortunes have been made in America over twentieth century demonstrates a developing basis of wealth, which mirrored the economy in many ways, in terms of both stock market movements and growing (or declining) industries.

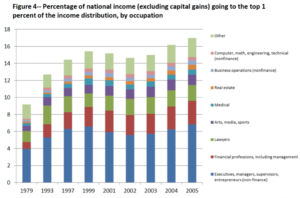

Occupations among the top income earners in the modern era, excluding capital gains, merit closer scrutiny.93The story is very similar when capital gains are included. Bakija et al., supra note 86, at 17–18, 35–36 tbls. 2 & 2a. Executives, managers, and supervisors in non-finance industries represented over 30% of taxpayers in the top one percent between 1979 and 2005, though this category decreased from 36% at the beginning of the period to 31% by the end. Notably, salaried executives within this category decreased from 21% at the start to about 11% at the end of this period.94Id. at 17–18, 35 tbl. 2. Bakija et. al note that this change, which coincides with an increase in executives of closely held businesses, is consistent with their observation that the Tax Reform Act of 1986 encouraged transitions from C-corporation to S-corporation status. Id. at 18. Financial professions (including management) nearly doubled their position within the top one percent, growing from under 8% to almost 14% during this period.95Id. at 18, 35 tbl. 2. Other occupations remained more stable over the period, including: medical (15.7% in 2005), lawyers (8.4% in 2005), computer, math, engineering, technical (non-finance) (4.6% in 2005), and real estate (3.2% in 2005).96Id. at 35 tbl. 2.

The role of executives, managers, and supervisors (non-finance) and financial professionals including management is even more outsized when honing in on the top 0.1% of the income distribution. Here, executives, managers, and supervisors (non-finance) accounted for just over 48% in 1979 and 42.5% in 2005.97Id. at 37 tbl. 3. Salaried, non-finance executives in the top 0.1% fell from 32% to 14% during this period. Id. Financial professions including management increased from 11% of the top 0.1% in 1979 to 18% in 2005.98Id. Meanwhile, the other occupations mentioned hold the following positions in the top 0.1% in 2005: medical (5.9%), lawyers (7.3%), computer, math, engineering, technical (non-finance) (2.9%), and real estate (3.7%).99Bakija et al., supra note 86, at 37 tbl. 3.

Thus, executives, managers, and supervisors (non-finance) and financial professionals including managers have played an important role in the top one percent over the last several decades. Notably, while the shares earners within the top one percent for each category moved in conflicting directions (decreasing versus increasing, respectively), both categories saw their share of national income captured by its members increase substantially over this period. For executives, managers, and supervisors (non-finance) in the top one percent, their share of national income rose from 3.7% in 1979 to 6.4% in 2005; and the share of national income going to financial professionals in the top one percent increased from 0.8 to 2.8% during this period.100Id. at 19–20, 41 tbl. 6. These increases were so marked, in fact, that Bakija, Cole and Haim estimate that “these two occupation groups alone explain a majority of the increase in the income share of the top 1%, explaining 60% of the increase between 1979 and 2005, and 61% of the increase between 1993 and 2005.”101Id. at 20.

The occupations comprising the top income earners is perhaps not surprising given the earlier discussion of labor market trends—away from routine tasks toward non-routine tasks requiring a higher social adeptness.

Figure 6:102Id. at 56 fig. 4.

Further examination of the dispersion of incomes reveals that inequality is increasing not only across occupations, but withinoccupations, as well.103See id. at 8 (“There is abundant evidence from the labor economics literature that increases in earnings inequality have been ‘fractal’ in nature – almost regardless of how you define a group, including by occupation, earnings inequality has been increasing within that group.”). Bakija, Cole, and Haim’s 2012 analysis, for example, reveals “a large amount of divergence in the incomes of people within the same profession,” and very different income growth rates across professions, even restricting consideration to the top one percent of income earners.104Id. at 23; see also id. at 22 (“The key lessons of these tables are: (1) real income growth was high in almost all top-earning professions in all three income groupings; (2) despite that, there was substantial heterogeneity in income growth rates across professions; (3) there is substantial heterogeneity across occupations in the apparent degree of sensitivity of income to the business cycle and asset prices; and (4) there was major divergence over time between the incomes of the highest paid people within each profession and others in that profession, even when we restrict our attention to people in the top one percent of the national income distribution.”). They posit that both these factors “suggest that the causes of rising top income shares cannot just, or even primarily, be things that are changing in similar ways over time for everyone within the top one percent, such as federal marginal income tax rates.”105Bakija et al., supra note 86, at 24. This argument, again, has important implications for the antitrust connection—which would seem to be a factor that changes in (at least fairly) similar ways across time and across top income earners.

A significant share of executive pay, today, derives from stock options—most of which are treated as wage and salary compensation on tax returns when exercised.106Id. at 3–4. It was not always the case that a large portion of executive compensation came in the form of stock options. Indeed, it was not until the second half of the twentieth century that stock compensation began to take its modern role in executive compensation.107See, e.g., Carola Frydman & Raven E. Saks, Historical Trends in Executive Compensation 1936-2003, at 2 (January 18, 2007), https://perma.cc/Y439-3GKW. (“[T]he use of executive stock options . . . have risen as a fraction of average compensation every decade from the 1950s to the present.”). The role of stock options, and its connection to alleged monopoly profits cycle, is another point of interest for the antitrust discussion later on.

D. Conclusions and Proposed Causes

The literature examining the trends discussed thus far leads to three conclusions.108Additional literature from recent years includes: Boas Bamberger, Christian Homburg & Dominik M. Wielgos, Wage Inequality: Its Impact on Customer Satisfaction and Firm Performance, 85 J. Mktg. 24 (2021); Daron Acemoglu & Pascual Restrepo, Robots and Jobs: Evidence from U.S. Labor Markets, 128 J. Pol. Econ. 2188 (2020); John M. Amis, Johanna Mair & Kamal A. Munir, The Organizational Reproduction of Inequality, 14 Acad. Mgmt. Annals 195 (2020); David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson & John Van Reenen, The Fall of the Labor Share and the Rise of Superstar Firms, 135 Q.J. Econ. 645 (2020); David H. Autor, Work of the Past, Work of the Future, 109 Am. Econ. Ass’n. Papers & Procs. 1 (2019); Anne S. Tsui, Georges Enderle & Kaifeng Jiang, Income Inequality in the United States: Reflections on the Role of Corporations, 43 Acad. Mgmt. Rev. 156 (2018); Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez & Gabriel Zucman, Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for the United States, 133 Q.J. Econ. 553 (2018). First, the very top earners have had an outsized impact upon the distribution of income for as long as the data permits examination. Changes to the income shares being appropriated by the top 1%, even the top 0.1%, have tended to dictate whether the overall distribution is more or less skewed. Second, the composition of income has changed over the period observed: wage income is more important now than it was at the start of the period; while capital income began as an important indicator, it dropped following the Great Depression and World War II, before seeing a resurgence in recent years. Third, the trend of the very top earners increasing their share of the national income has continued to increase in recent decades, for so long as the data permits observation.

Simultaneously, there appears to have been a “carving out” of the traditionally middle-class occupations and wages. Thus, not only are the very top earners increasing their share; but the rest of the distribution is increasingly being funneled into either higher-education, higher-income jobs or lower-education, lower-income ones. This has led to polarization in both wages and jobs.

This literature also reveals potential explanations for the observed outcomes. For instance, unique factors present and following World War II are largely attributed with catalyzing the Great Compression, and with maintaining a more modest share of income being captured by the very top earners in the years that followed.109Frydman & Saks, supra note 107, at 16. These factors included governmental wartime policies, like the National War Labor Board (“NWLB”), and market forces, like the increased demand for (comparatively) lower-skilled manufacturing roles.110Id. at 23–28; see also Claudia Goldin & Lawrence F. Katz, The Returns to Skill in the United States Across the Twentieth Century, at 26 (Nat’l Bureau of Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 7126, 1999), https://perma.cc/8T5C-5K6M (“The two largest and most persistent periods of wage structure narrowing (the late 1910s and the 1940s) were also ones of world war, inflation, tight labor markets, strong demand for manual workers, rising union strength, and substantial government intervention in the labor market. Both episodes strongly suggest the importance of labor market institutions and the role of wars in the erosion of customary wage differentials.”). Moreover, the Great Compression tightened “both the upper and lower tails of the distribution.”111Goldin & Margo, supra note 14, at 32. The power of this time period in constricting inequality in income distribution derived not only from a significant dip in the share of income flowing to the top income earners, but also from a rising minimum wage which “continued to pull up the bottom of the wage distribution.”112Id. This fact bears important policy implications for current attempts to equalize income distribution.

Scholars have explored the evolution of U.S. tax policy since the Great Depression or World War II eras to the present. This work consistently finds that tax policy does, in fact, play a role in the distribution of incomes, particularly of the very top earners.113See, e.g., Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez & Stefanie Stantcheva, Optimal Taxation of Top Labor Incomes: A Tale of Three Elasticities, 6 Am. Econ. J.: Econ. Pol’y 230, 246 fig. 1 (2014); Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 24 (“We are not the first to propose progressive taxation as an explanation for the decrease in top shares of income and wealth. Lampman [1962] did as well, and Kuznets [1955] explicitly mentioned this mechanism as well as the shocks incurred by capital owners during the 1913 to 1948 period, before presenting his inverted U-shaped curve theory based on technological change.”); see also Frydman & Saks, supra note 107, at 2 (“The widespread adoption of restricted stock options directly after the passage of the 1950 Revenue Act suggests that compensation arrangements were highly responsive to tax policy.”). Indeed, work examining income distribution over the twentieth century predicted that “the decline in income tax progressivity since the 1980s . . . might again produce in a few decades levels of wealth concentration similar to those at the beginning of the century.”114Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 24. While tax policy, and income tax policy in particular, is not a complete explanatory factor, it does appear to be a powerful one.115Id. at 14 (“[T]he pattern of top income shares cannot be explained fully by the pattern of top income tax rates.”).

Additional factors frequently cited as contributing to trends in income distribution, especially relating to job and wage polarization, include skill-biased technical change, and globalization and offshoring.116See generally Autor et al., supra note 11, at 1338; David H. Autor, David Dorn & Gordon H. Hanson, The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States, 103 Am. Econ. Rev. 2121 (2013) (“In our main specification, import competition explains one-quarter of the contemporaneous aggregate decline in US manufacturing employment.”). Still other work identifies a “particularly important role for financial market asset prices, shifting of income between the corporate and personal tax bases, and possibly corporate governance and entrepreneurship, in explaining the dramatic rise in top income shares.”117Bakija et al., supra note 86, at 27; see also Frydman & Saks, supra note 107, at 3 (“Thus, a number of other factors also have influenced changes in the compensation arrangements of top officers over time. Among other explanations, corporate governance, social norms, the market for corporate control, and the labor market for executives, may have contributed to the evolution of executive compensation.”). Bakija et al. also discuss the importance of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which reduced the top personal tax rate below the top corporate rate. They note that this “created an incentive to change one’s business to a pass-through-entity such as an S-corporation, the income of which is taxed only once at the personal level. This has important implications for the income inequality and taxable income elasticity literatures, because it suggests that part of the difference in top incomes before and after 1986 does not reflect the creation of new income, but rather income that was previously not reported in the data (which is derived from personal income tax returns) and now is.” Bakija et al., supra note 86, at 9. Though they note that income shares going to the top 0.1% continue to increase even restricting review to later periods. As Goldin and Katz explain, wage structure and its compression last century “was larger in magnitude, more drawn out in time, and more complicated in its reasons than has previously been thought. Similarly, the widening of the wage structure and the increase in the returns to education in the post–1970s period . . . have been shown to be abundantly complex.”118Goldin & Katz, supra note 110, at 27.

While many culprits have been identified in this literature, one conspicuously absent from rigorous review (so far) is antitrustlaw and policy. The corpus of work empirically examining the income distribution trends largely omits discussion of this particular suspect.119Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 24 n.28 (DeLong “points out the potential role of antitrust law,” but does not further investigate this theory). Some work discusses more broadly the roles of regulation (or deregulation), labor market institutions (including unions), as well as societal pressures to constrain excess, particularly in times of economic hardship, which places downward pressure on the highest wages—pressure which seems to have dissipated from previous peaks around the World Wars and the Great Depression.120See, e.g., Piketty & Saez, supra note 29, at 34 (“We think that this pattern of evolution of inequality is additional indirect evidence that nonmarket mechanisms such as labor market institutions and social norms regarding inequality may play a role in the setting of compensation at the top. The Great Depression and World War II have without doubt had a profound effect on labor market institutions and more generally on social norms regarding inequality.”);Stiglitz, supra note 8, at 198–99 (discussing deregulation and inequality). But none of this work (yet) grapples directly and meaningfully with the role of antitrust law and enforcement, specifically.

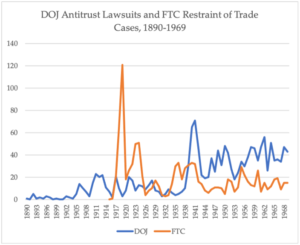

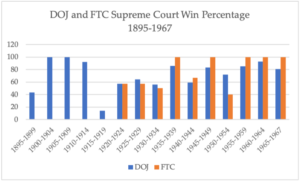

II. Antitrust Trends

There is a simple, but popularly persuasive, story that critics of modern antitrust offer regarding antitrust and income inequality: income inequality has skyrocketed since the 1980s, following the Court’s formal adoption of the consumer welfare standard; this standard weakened antitrust enforcement and, in doing so, contributed to the rising inequality trend observed since. The next Section more closely analyzes this argument and the means by which modern antitrust policy is alleged to facilitate income inequality growth. Understanding the history of antitrust law and policy both before and after the 1980s creates a fuller picture upon which to base a comparison of the two phenomena.

A. Adoption of the Sherman Act and Early Enforcement Efforts

In 1890, Congress passed the inaugural federal antitrust legislation, the Sherman Act, laying the foundation for the United States’ federal antitrust regime.121Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7. The Sherman Act’s broad language proscribes “[e]very contract, combination . . . or conspiracy[] in restraint of trade,” as well as monopolization, attempted monopolization, and conspiracies to monopolize.122Id. Its sweeping mandates left significant work for the courts in deciphering and rendering workable the Act’s prohibitions.123See, e.g., Elyse Dorsey, Antitrust in Retrograde: The Consumer Welfare Standard, Socio-Political Goals, and the Future of Enforcement, in The Global Antitrust Institute Report on the Digital Economy 109, 115–16 (Joshua D. Wright & Douglas H. Ginsburg eds., 2020 ed.).

As courts struggled for the first several decades in this herculean task, many scoured the legislative history of the Act for any valuable insights that might be gleaned.124See, e.g., Temp. Nat’l Econ. Comm., 76th Cong., Investigation of Concentration of Economic Power, Monograph No. 16, Antitrust in Action 10 (Comm. Print 1940) [hereinafter TNEC Antitrust in Action] (“A great deal has been said about the purpose of Congress in passing the act.”); see also Douglas H. Ginsburg, Bork’s “Legislative Intent” and the Courts, 79 Antitrust L.J. 941 (2014) (identifying numerous interpretations proferred). The task continues to this day, with any agreement or final resolution continuing to evade discovery. Despite the apparent futility of this effort, some scholars today continue to rely upon legislative history to argue that antitrust should further not only economic goals, but socio-political ones, as well.125See, e.g., Lina Khan & Sandeep Vaheesan, Market Power and Inequality: The Antitrust Counterrevolution and Its Discontents, 11 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 235, 270, 277–79 (2017) (“The congressmen and senators involved in the debates preceding the passage of the principal antitrust laws voiced a number of concerns, including the protection of consumers and suppliers from firms with market power, the defense of small businesses from the predatory tactics of large rivals, and the preservation of democracy. Efficiency was not on Congress’s radar in 1890 or 1914.”); Sandeep Vaheesan, The Profound Nonsense of Consumer Welfare Antitrust, 64 Antitrust Bull. 479, 480 (2019) (“The drafters of these landmark statutes sought to restrict corporate power over consumers, workers, suppliers, and rivals.”). Others contend that Congress’s intent in passing the Act was to promote economic efficiency or consumer welfare alone.126See, e.g., Robert H. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox 61–66 (1978) (“The legislative history of the Sherman Act, the oldest and most basic of the antitrust statutes, displays the clear and exclusive policy intention of promoting consumer welfare.”); Robert H. Lande, Wealth Transfers as the Original and Primary Concern of Antitrust: The Efficiency Interpretation Challenged, 34 Hastings L.J. 65, 68 (1982) (“Congress passed the antitrust laws to further economic objectives, but primarily objectives of a distributive rather than of an efficiency nature.”). Still others identify protecting special interest groups representing small businesses as the true driving force behind the Act’s passage—this type of rent-seeking behavior by interested stakeholders is an important undercurrent coursing through antitrust history, which will be examined further below.127See, e.g., Herbert Hovenkamp, Enterprise and American Law, 1836-1937, at 246–47 (1991) (“[T]here is equally good evidence that Congress’s rhetoric does not fully account for its true motives, which were to protect various special interest groups representing small business. For example, Senator John Sherman himself may have been the cat’s-paw of the independent oil producers and refiners, who wanted protection from both Standard Oil Company and the railroads. Among the most aggressive lobbying organizations were several associations of salesmen and independent distributors, whose positions in the American economy were threatened by larger, vertically integrated firms.”); Thomas J. DiLorenzo, The Origins of Antitrust: Rhetoric vs. Reality, 13 Regul. 26, 27 (1990) (“[T]he Sherman Act was never intended to protect competition. It was a blatantly protectionist act designed to shield smaller and less efficient businesses from their larger competitors.”). And others yet observe that the legislative history has been meticulously combed, to little avail, and that today’s efforts and discussions should focus instead upon the lived experiences of applying the Act over the last 130 years.128See, e.g., TNEC Antitrust in Action, supra note 124, at 10–11 (“In a search for intent the record has been thumbed through with meticulous care and to little purpose.”); Dorsey, supra note 123, at 114 (“Perhaps more important—and certainly more informative—than the intent of the 1890 (and later) congressmen and language that, by definition, did not make it into the statutes, is the courts’ practical history of enforcing the laws as enacted.”).

Throughout the twentieth century, the Sherman Act’s primary provisions—sections 1 and 2—remained largely unchanged. Some have argued that “[o]ne of the most significant changes in antitrust enforcement of the Gilded Age” derived not from “new legislation, but from a change in the approach taken to the enforcement of existing law when [Theodore] Roosevelt became president” suddenly in 1901 after President McKinley’s assassination.129Richard B. Baker, Carola Frydman & Eric Hilt, Political Discretion and Antitrust Policy: Evidence from the Assassination of President McKinley 4 (Nat’l Bureau Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 25,237, 2018), https://perma.cc/PPP4-D4BQ; see also Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets 160 (2019). Nonetheless, additional legislation was subsequently adopted, which contributed to the developing regulatory landscape. Notably, in 1914, Congress passed the Clayton Act,13015 U.S.C. §§ 12–27 (as amended). primarily addressing mergers,131Sections 3, addressing exclusive dealing, and 8, addressing interlocking directorates and officers, were also important additions. and the Federal Trade Commission Act,13215 U.S.C. §§ 41–58 (as amended). establishing the Commission (or the FTC), its jurisdiction, and other legal authorities. Congress passed the Robinson-Patman Act in 1936, outlawing certain price discrimination in the sale of commodity products.13315 U.S.C. § 13. The Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 closed a loophole in existing legislation, prohibiting asset purchases (not just stock), and further intended to both permit challenges to vertical mergers and strengthen horizontal merger enforcement.134Celler-Kefauver Act, Pub. L. No. 81-899 (1950). In 1976, Congress passed the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act,13515 U.S.C. § 18a. promulgating the modern pre-merger notification system which prevents parties from consummating certain mergers without first notifying the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) and U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and allowing for statutorily prescribed review process.

Early antitrust decisions reflect the difficulty of conceptualizing the Sherman Act’s broad mandates and identifying a consistent, coherent set of priorities. For instance, the courts issued decisions finding that the Act should protect “small dealers and worthy men,”136United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. 290, 323–24 (1897). and “put an end to great aggregations of capital because of the helplessness of the individual before them.”137United States v. Aluminum Co. of Am., 148 F.2d 416, 428 (2d Cir. 1945). But these decisions simultaneously acknowledged that higher prices to consumers—perhaps the most individualistic group—might result from the positions taken, without delving into why these worthy individuals should be imposed upon.138See, e.g., Utah Pie Co. v. Cont’l Baking Co., 386 U.S. 685, 703 (1967) (reversing a ruling that would have facilitated lower prices); Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 344 (1962) (explaining “higher costs and prices might result”); Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. at 323–24 (finding a “[m]ere reduction in the price of the commodity dealt” was not a sufficient consideration). Other court decisions similarly displayed convoluted analysis, such as in United States v. Aluminum Company of America,139148 F.2d 416 (2d Cir. 1945). where the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit specifically found that the “successful competitor, having been urged to compete, cannot be turned upon when he wins,” but then condemned the defendant expanding its capacity to meet consumer demand.140Id. at 430; see also United States v. U.S. Steel Corp., 251 U.S. 417, 451 (1920) (“The Corporation is undoubtedly of impressive size and it takes an effort of resolution not to be affected by it or to exaggerate its influence. But we must adhere to the law and the law does not make mere size an offence or the existence of unexerted power an offence. It, we repeat, requires overt acts and trusts to its prohibition of them and its power to repress or punish them. It does not compel competition, nor require all that is possible.”); United States v. Grinnell Corp., 384 U.S. 563, 570–71 (1966). In United States v. Topco Associates, Inc.,141405 U.S. 596 (1972). the Supreme Court condemned a joint venture of small and mid-sized regional supermarket operators which allowed the members to offer private label products they could not offer on their own, and which positioned them to better compete with the larger chains while lowering prices to consumers.142Id. at 608–11.

As Professor Hovenkamp notes, within the first seven years of its existence, lower courts found labor unions to have violated the Sherman Act in a dozen cases.143Hovenkamp, supra note 127, at 229 (“[A]lthough economists and many statesmen had substantial doubts about the effectiveness of the Sherman Act against industrial combinations and trusts, from the start the new statute was perceived to be a powerful union-busting device.”). This seems difficult to reconcile with an intent to protect “small dealers and worthy men.”144United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166 U.S. 290, 323–24 (1897). Congressmen, in fact, debated the proper statutory treatment of unions and organized labor—as they did many other concerns—while they considered the draft legislation. Senator John Sherman proposed an amendment, which was adopted by a Senate voice vote but later struck out (along with several other amendments) by the Judiciary Committee.145Hovenkamp, supra note 127, at 229. Yet again, there is not complete agreement as to the implications of the considered and rejected labor amendment to the original statute.146See id. at 229 (citing 21 Cong. Rec. 2611-2612, 2728-2731 (1890); Alpheus T. Mason, Organized Labor and the Law 122–27 (1925); Joseph A. Joyce, A Treatise on Monopolies and Unlawful Combinations or Restraints 175 (1911); James A. Emery, Labor Organizations and the Sherman Law, 20 J. Pol. Econ. 599, 604–06 (1912); Edward Berman, Labor and the Sherman Act 11–51 (1930)).

Antitrust decisions were, early on, typically marked by formalistic thinking and deep skepticism of novel conduct. The courts frequently, and often summarily, condemned mergers between firms with very small market shares and nearly all vertical arrangements.147See, e.g., United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270, 278–79 (1966); United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 323–24 (1963); Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 346 (1962); Herbert Hovenkamp, Progressive Antitrust, 2018 U. Ill. L. Rev. 71, 84 (2018) (“Antitrust policy from the New Deal through the early 1970s became an economically irrational war on vertical integration of all types.”). These decisions earned antitrust enforcement in the mid–twentieth century the title of the “inhospitality tradition.”148See Elyse Dorsey, Anything You Can Do, I Can Do Better—Except in Big Tech?: Antitrust’s New Inhospitality Tradition, 68 Kan. L. Rev. 975, 979–85 (2020).

B. Mid–Twentieth Century: The Antitrust Revolution

Antitrust was at an inflection point by the mid–twentieth century. Criticisms of its numerous failures, inconsistencies, and incoherencies resounded widely and loudly. Antitrust courts would soon chart a clearer path, the development of which was decades in the making.

By many accounts, antitrust law in the mid–twentieth century was in crisis.149See, e.g., Bork, supra note 126, at 3–11. Tension had been building almost since the inception of the Sherman Act. By 1932, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s chief antitrust advisor Milton Handler decried the entirety of Supreme Court antitrust jurisprudence as “singularly free of enlightenment,” noting that “[c]onflicting theories, divergent explanations of the facts and opposing contentions form an impenetrable jungle of words,” and concluding that to “reconcile the rationes decidendi of the opinions is an impossibility.”150Milton Handler, Industrial Mergers and the Anti-Trust Laws, 32 Colum. L. Rev. 179, 182–83 (1932). Justice Potter Stewart, reviewing this corpus of caselaw some three decades later came to largely the same conclusion, criticizing that the “sole consistency that I can find is that in litigation under § 7, the Government always wins.”151Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. at 301 (Stewart, J., dissenting).

The criticisms of antitrust were relentless, and struck at the core of the doctrine. These criticisms called into question what antitrust law truly sought to accomplish, as well as its capacity to do so. A vigorous debate marshaling esteemed experts of many various viewpoints followed, ultimately ushering antitrust into the modern age.

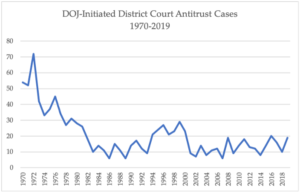

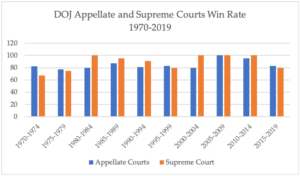

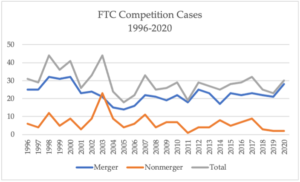

Recently, however, some commentators have argued that the mid-twentieth century, from about the 1940s to the end of the 1970s, represents a “golden era of antitrust action.”152Maurice E. Stucke & Ariel Ezrachi, The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the U.S. Antitrust Movement, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Dec. 15, 2017) https://perma.cc/5SYB-5LMX; see also The Consumer Welfare Standard in Antitrust: Outdated or a Harbor in a Sea of Doubt: Hearing Before the Subcomm. on Antitrust, Competition & Consumer Rights of the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 115th Cong. 8 (2017) (statement of Barry C. Lynn, Executive Director, Open Markets Institute), https://perma.cc/8B88-TL7Z (“This philosophy and practice of antimonopoly proved to be a phenomenal political and economic success. Through the heart of the 20th Century, America was at one and the same time the most free, the most prosperous, and the most powerful nation on earth.”). These proponents paint a rosy picture of antitrust law and policy during this time, arguing that it directly and meaningfully contributed to the lower levels of income inequality observed during this period.153Matt Stoller, The Return of Monopoly, The New Republic (July 12, 2017), https://perma.cc/MTJ7-B2D4. (“The anti-monopoly principle that [Thurman] Arnold and [Justice] Brandeis established—the idea that economic power should be decentralized and spread into many hands—became the basis of a new social contract. . . . America entered a golden age of egalitarian prosperity . . . .”); Anti-Monopoly Basics: Democracy & Monopoly, Open Mkts. Inst., https://perma.cc/B39U-YWWB(“This anti-monopoly system [from the 1930s to the 1980s] had a profound effect on the American economy and, crucially, on American democracy.”); see also Dorsey, supra note 123, at 141–43 (discussing these arguments).