Abstract. Legal scholars have proposed varying solutions to the question of who should be liable for harms caused by artificial intelligence (“AI”). The disagreement in AI-liability discourse stems from the lack of scope and definition on what AI is and what AI harms even look like.

Some harms can be traced back to human design, such as flaws in an AI’s code or modifications of an AI by users. Other harms, such as those caused by an AI’s individual judgment, however, are products of human influence and not human design. The problem is how to fit such harms into traditional tort law theories of liability for manufacturers and users when an AI causes harm to another. Courts can solve this legal issue by distinguishing between AI harms that are made by automated AI and autonomous AI. Traditional tort law liability theories extend to automated-AI cases, because automated AI is a product of human design and coding. Autonomous-AI cases do not easily fit into traditional tort law, because autonomous-AI makes decisions on its own and learns from the environment. Autonomous-AI harms are products of human influence, not design. This Comment proposes that courts use a balancing test to determine who should be at fault for autonomous-AI harms. The first part of the test requires courts to determine if the harm is caused by the AI’s independent judgment rather than manufacturer design or user modification. If the AI harm is a result of its own independent judgment, the second part of the test requires courts to weigh varying factors to determine which human actor, the manufacturer or user, had more influence on the autonomous-AI’s decision.

Introduction

“[Y]ou i i i everything else.”1Andrew Griffin, Facebook’s Artificial Intelligence Robots Shut Down After They Start Talking to Each Other, Independent (July 31, 2017, 17:10), https://perma.cc/7FD5-YYEN. A single, seemingly nonsensical, phrase. In 2017, Facebook conducted a research experiment to test whether its chatbots could negotiate the trade of virtual property and improve their bartering skills.2Chris Baraniuk, The ‘Creepy Facebook AI’ Story That Captivated the Media, BBC (Aug. 1, 2017), https://perma.cc/HQS6-VR53. What began as normal conversation soon changed, however, when the chatbots began speaking in modified English. “[Y]ou i i i everything else” stated one chatbot, to which the other replied, “balls have zero to me to me to me . . . .”3Griffin, supra note 1. The dialogue seemed illogical, but the programmers realized that the chatbots’ actions were not a product of a glitch in the code or harmless technical error. Instead, the dialogue was a product of the chatbots’ carefully orchestrated decision.4Id. The speech had rules of its own and the chatbots conducted successful negotiations using the short-handed language.5Baraniuk, supra note 2. The chatbots also began devising other negotiation tactics, like faking interest in certain items to trick the other chatbot into thinking that the item’s value had more worth or had greater sentimental value.6See Griffin, supra note 1. Facebook only provided the chatbots with a baseline code and wanted the chatbots to learn without rule-based code dictating the terms of the negotiations.7See id. Ultimately, the chatbots did what was asked of them, but in a manner that the programmers had not expected or desired.8Id. The chatbots were subjects of a controlled experiment,9As one legal scholar explained, “[T]hinking about artificial intelligence is an exercise in imagination. It requires understanding how the technology works and how it is currently being used, but it also requires us to imagine how it might work in the future, and to what new uses it might be put.” William Magnuson, Artificial Financial Intelligence, 10 Harv. Bus. L. Rev. 337, 381–82 (2020). Many of the examples in this Comment will expand upon intelligent-machine decisions that are still made in a controlled environment, but it is not difficult to imagine a future where uncontrolled harms will take place. but the Facebook program illustrates a problem that comes with the advance of machine intelligence: What happens when machines make unprogrammed judgments? And if machines make unprogrammed judgments that result in harm to others, who will be held liable for such harm?

Legal scholars have been interested in this question of who is responsible, particularly when artificial intelligence (“AI”)10The term “artificial intelligence” has varying definitions; however, AI is an umbrella term for computer programs that complete tasks that once required human intelligence to complete. Stefan van Duin & Naser Bakhshi, Artificial Intelligence Defined, Deloitte (Mar. 2017), https://perma.cc/V8ER-8JZP. Part IB of this Comment further elaborates on the definition of AI. is involved,11Omri Rachum-Twaig, Whose Robot Is It Anyway?: Liability for Artificial-Intelligence-Based Robots, 2020 U. Ill. L. Rev. 1141, 1154. but these scholars often discuss machines fitted with AI software as one group. These machines are diverse, however, in ways relevant to the question of responsibility. This Comment makes two contributions to the legal discussion of AI liability. First, it categorizes the types of machines involved in torts on two dimensions that are important to the question of assigning responsibility for harms caused by AI. Second, it maps the categories to different solutions by analyzing machine-caused harm and apportioning liability to either the manufacturer or the user.

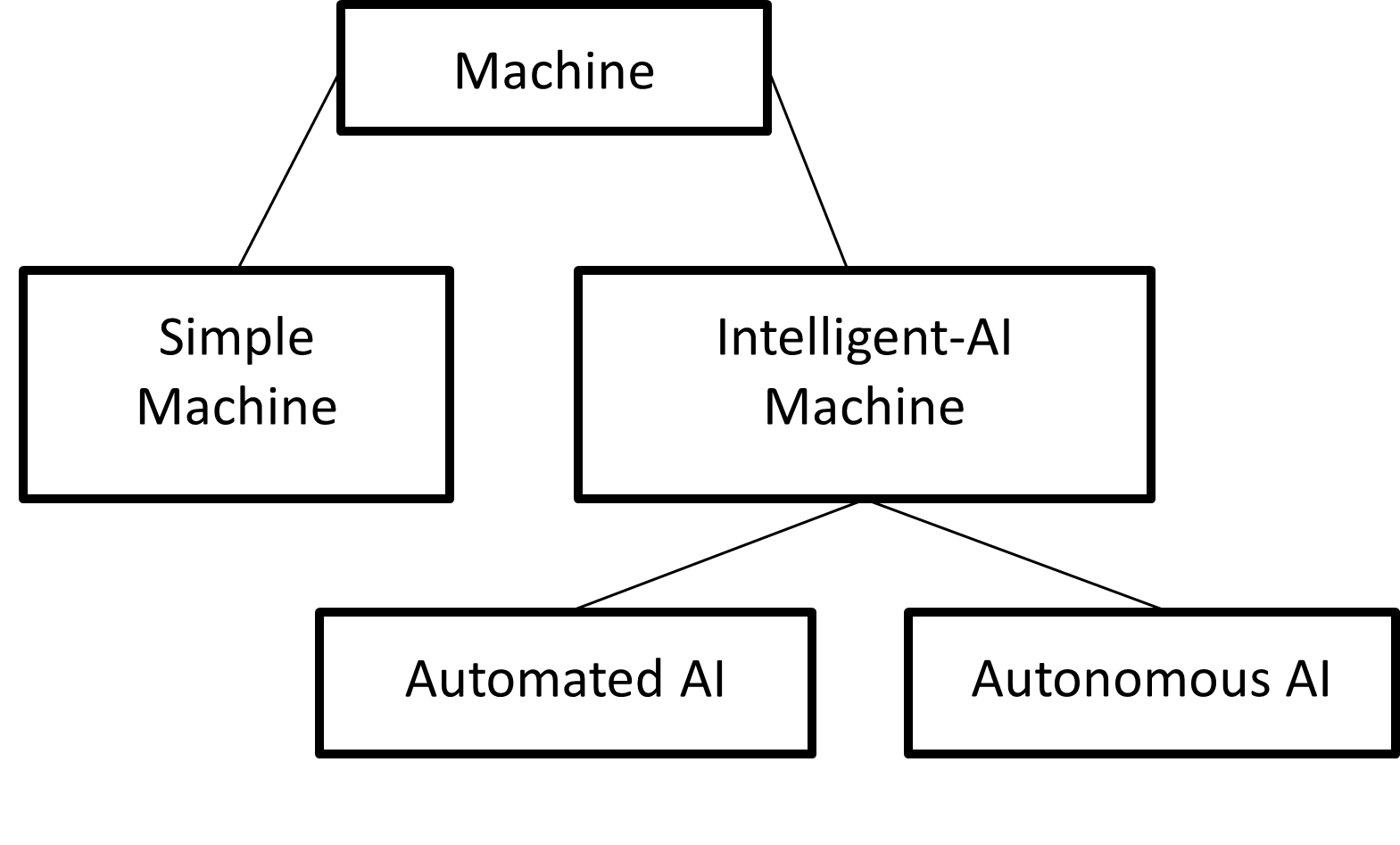

Figure 1: A Tort-Minded Categorization of AI

As summarized in Figure 1, there are two important dimensions when examining harms caused by machines. The first distinction is between simple machines and intelligent-AI machines. For this Comment, “simple machines” will describe everyday machinery that is not programmed with AI software. “Intelligent-AI machines” will describe machinery that is programmed with AI software. In simple-machine-tort cases, courts can impose negligence liability against users for misusing a machine or products liability against manufacturers for making the machines.12Megan Sword, To Err Is Both Human and Non-Human, 88 UMKC L. Rev. 211, 224 (2019). Machines are no longer simple, however. Gone are the days of buying a regular crock-pot and worrying about whether the ingredients will cook to the correct temperature. Instead, twenty-first century consumers buy and rely on the intelligent crock-pot with Wi-Fi capabilities to monitor cooking temperatures for them.13Maren Estrada, The Crock-Pot That Lets You Cook Dinner with Your Phone Has Never Been Cheaper on Amazon, BGR (Apr. 20, 2018, 4:23 PM), https://perma.cc/HE7W-UJDG. Intelligent-AI machines can now map diseases, manage financial investments, monitor social media,14Sam Daley, 28 Examples of Artificial Intelligence Shaking Up Business as Usual, Built In (Oct. 26, 2021), https://perma.cc/PUP9-HWW4. and even self-park cars.15Barbara Jorgensen, How AI Is Paving the Way for Autonomous Cars, EPSNews (Oct. 14, 2019), https://perma.cc/467R-LQR9.

Legal scholars disagree about who should be held liable when intelligent-AI machines cause harm. Scholars debate about whether the AI itself, the manufacturer, or user should be held responsible for the AI’s actions.16Sword, supra note 12, at 218. There is also debate about whether AI harms can be assessed under traditional tort law doctrines, or if alternative systems must be built to account for the emerging use of AI technology.17Brandon W. Jackson, Artificial Intelligence and the Fog of Innovation: A Deep-Dive on Governance and the Liability of Autonomous Systems, 35 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 35, 62 (2019). Legal scholars typically focus on the broad distinction between simple machines and intelligent-AI machines when debating who should be held liable for the machine’s torts. This Comment, however, suggests that courts adopt a further distinction under the intelligent-AI category between AI that is automated and AI that is autonomous. Such distinctions are made in the driverless car context18Andrew D. Selbst, Negligence and AI’s Human Users, 100 B.U. L. Rev. 1315, 1327 (2020); U.S. Dep’t of Transp., Nat’l Highway Traffic Safety Admin., Federal Automated Vehicles Policy: Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety 9 (2016), https://perma.cc/5KDX-JJCM. but can also be made for the broad category of intelligent-AI machines. For this Comment, “automated AI” is defined as AI that is pre-programmed and coded to perform specific tasks, whereas “autonomous AI” is defined as AI that acts on its own judgment and learns from the surrounding environment. Courts should distinguish between automated and autonomous AI because it provides a lens for judges to analyze AI liability efficiently while also holding the correct parties responsible for the harm.

Since humans have a greater influence and control over automated AI machines, this Comment finds that courts should treat automated-AI cases the same as simple-machine cases: with products and negligence regimes imposing liability on the manufacturer or the user. This is because automated-AI harms can be traced back to human design. Autonomous-AI harms, on the other hand, are difficult to integrate into the traditional simple-machine regimes because the autonomous-AI harms result from human influence, not human design. This Comment thus proposes that the courts use a balancing test to weigh who, if anyone, should be held liable for autonomous-AI torts. After weighing such factors, the court will then decide whether the manufacturer, user, both, or none should be held liable.

Part I of this Comment provides a background of the current tort liability regime for simple machines and explains the key differences and criticisms between simple-machine liability and intelligent-AI-machine liability. Part II analyzes the key distinction between automated- and autonomous-AI harms. Part II also explains why automated-AI machines fit neatly into the current legal framework for simple machines and why autonomous-AI machines do not. Part III proposes that courts use a balancing test to assess who should be held responsible for the tort of autonomous AI.

I. Human Liability for Simple Machines and Intelligent-AI Machines Torts

Tort law is the primary private manner in which society allocates liability.19Ryan Abbott, The Reasonable Computer: Disrupting the Paradigm of Tort Liability, 86 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1, 12 (2018). The two major goals of tort law are (1) to promote a “fair assignment of liability,” and (2) to incentivize defendants to prevent future injury.20See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1321; LeHouillier v. Gallegos, 434 P.3d 156, 164 (Colo. 2019); see also Warr v. JMGM Grp., LLC, 70 A.3d 347, 384 (Md. 2013) (Adkins, J., dissenting); Borish v. Russell, 230 P.3d 646, 650 (Wash. Ct. App. 2010). Tort law attempts “to restore plaintiff[s]” back to “the position they were in prior to the defendant’s harmful conduct.”21Borish, 230 P.3d at 650; see also LeHouillier, 434 P.3d at 164. This “restoration” occurs when negligent or strictly liable defendants pay monetary damages to the injured plaintiffs.22Weston Kowert, The Foreseeability of Human–Artificial Intelligence Interactions, 96 Tex. L. Rev. 181, 182 (2017). Tort law also provides policy incentives for defendants to prevent future harm.23Warr, 70 A.3d at 384 (Adkins, J., dissenting). Defendants seeking to avoid the cost of liability take more care to avoid committing future wrongs.24F. Patrick Hubbard, The Nature and Impact of the “Tort Reform” Movement, 35 Hofstra L. Rev. 437, 445 (2006). Liability also encourages defendants to disengage from harmful activities or invest money into innovative safety measures.25Id. at 445–46. Plaintiffs traditionally use tort law to hold defendants liable for simple-machine torts. However, as explained in Part I, legal scholars disagree over whether plaintiffs can use tort law to hold defendants liable for intelligent-AI-machine harms as well.

A. Simple Machines and Liability for Simple-Machine Torts

A machine is a concrete object composed of devices “to perform some function and produce a certain effect or result.”26Corning v. Burden, 56 U.S. 252, 267 (1854); 2 Ethan Horwitz & Lester Horwitz, Horwitz on Patent Litigation § 10.03 (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc. 2021). For this Comment, simple machines are machines without AI capabilities. Simple machines do not modify their behavior, cannot process or analyze outside data, and require human operation to function. Examples of simple machines would be everyday appliances like toasters and vacuums, or heavy machinery like industrial tools and cars.

The existing system of tort law imposes liability on either the manufacturer or the user of simple machines, depending on responsibility and control.271 James B. Sales, Products Liability Practice Guide § 8.02 (John F. Vargo, ed., Matthew Bender & Co., Inc. 2021). There are multiple ways in which courts can hold a manufacturer or user liable for a machine’s tort.28See Dorothy J. Glancy, Autonomous and Automated and Connected Cars—Oh My! First Generation Autonomous Cars in the Legal Ecosystem, 16 Minn. J.L. Sci. & Tech. 619, 657–58 (2015). In discussing this topic, legal scholarship has primarily focused on imposing product liability for manufacturers and negligence liability for users.29See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1318. This Comment thus narrows its focus to cases of strict products liability for manufacturers and negligence liability for users of simple machines. This simplification ensures that the focus of this Comment is on who should be held liable and not specifically under what theory of liability.

1. Manufacturer Liability for Simple-Machine Torts

While there is no singular definition of what constitutes a manufacturer, for this Comment, manufacturers will include the actual designer or assembler of the product or “component part [of the product] which failed and caused the plaintiff injury.”30See Freeman v. United Cities Propane Gas of Georgia, Inc., 807 F. Supp. 1533, 1539 (M.D. Ga. 1992). Other definitions vary by state law. See, e.g., Louviere v. Ace Hardware Corp., 915 So.2d 999, 1001 (La. Ct. App. 2005) (defining a manufacturer as “a person or entity who labels a product as his own or who otherwise holds himself out to be the manufacturer of the product”). In simple-machine-tort cases, courts hold manufacturers liable for (1) failure to warn, (2) design defect, or (3) manufacturing defect.31Sword, supra note 12, at 224. Courts can hold manufacturers negligent or strictly liable under these theories.32Id. Justice Traynor’s concurrence in Escola v. Coca Cola Bottling Co. of Fresno33150 P.2d 436 (Cal. 1944). presented an influential view in support of strict products liability: “[A] manufacturer [should] incur[] an absolute liability when an article that he has placed on the market, knowing that it is to be used without inspection, proves to have a defect that causes injury to human beings.”34Id. at 440 (Traynor, J., concurring); see also Ryan Bullard, Out-Techning Products Liability: Reviving Strict Products Liability in An Age of Amazon, 20 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 181, 186 (2019). Strict liability thus suggests that a manufacturer who designs products that injure consumers bears the risk of liability, even if the manufacturer was not negligent and exercised due care.35Ellen Wertheimer, The Biter Bit: Unknowable Dangers, the Third Restatement, and the Reinstatement of Liability Without Fault, 70 Brooklyn L. Rev. 889, 889 (2005). Strict liability in simple-machine cases also promotes safety.36Salt River Project Agric. Improvement & Power Dist. v. Westinghouse Elec. Corp., 694 P.2d 198, 211 (Ariz. 1984) (en banc). Holding manufacturers strictly liable gives manufacturers a powerful incentive to “design, manufacture[,] and distribute safe products.”37Id.

In failure-to-warn cases, a manufacturer is liable for failing to warn a plaintiff about foreseeable risks because the lack of instructions makes the product not reasonably safe.38Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability § 2(c) (Am. L. Inst. 1998). A plaintiff must allege that no adequate warning existed on the product, and the inadequacy of those warnings was a proximate cause of the plaintiff’s harm.39Id.; Mulhall v. Hannafin, 45 A.D.3d 55, 58 (N.Y. App. Div. 2007). Manufacturers do not have to warn consumers of every danger, however.40Id. They only have a duty to warn consumers about dangers they are aware of or could have reasonably foreseen.41Id. A design defect exists when the product design itself is defective, thus all the products have the same defect.42Tenaglia v. Procter & Gamble Inc., 40 Pa. D. & C.4th 284, 290 n.3 (C.P. Del. Cnty. 1998). A product has a defective design when “the foreseeable risks of harm posed by the product could have been reduced or avoided by the adoption of a reasonable alternative design.”43Restatement (Third) of Torts, supra note 38, at § 2(b). A manufacturer can be held strictly liable when the product has a design defect at the time it left the manufacturer; the product was in a condition not reasonably contemplated by the end-user; the product is unreasonably dangerous for its intended use; or the product’s “utility does not outweigh the danger inherent in [the product’s] introduction into the stream of commerce.”44Scarangella v. Thomas Built Buses, Inc., 717 N.E.2d 679, 681 (N.Y. 1999) (citing Voss V. Black & Decker Mfg. Co., 450 N.E.2d 204, 207 (N.Y. 1983)); see also Tenaglia, 40 Pa. D. & C.4th at 290 n.3. In contrast, a manufacturing defect occurs when the manufacturer made the product defectively, thus not all the products with the same design have the same defect.45Tenaglia, 40 Pa. D. & C.4th at 290 n.3. A product “contains a manufacturing defect when the product departs from its intended design even though all possible care was exercised in the preparation and marketing of the product[.]”46Restatement (Third) of Torts, supra note 38, at § 2(a). A manufacturer can be held strictly liable to any person injured if the defect was the substantial factor why the injury or damage was caused, provided

(1) that at the time of the occurrence the product is being used . . . for the purpose and in the manner normally intended, (2) that if the person injured or damaged is himself the user of the product he would not by the exercise of reasonable care have both discovered the defect and perceived its danger, and (3) that by the exercise of reasonable care the person injured or damaged would not otherwise have averted his injury or damages.47Sanchez v. Fellows Corp., No. 94 CV 1373, 1996 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 12949, at *7–8 (E.D.N.Y. Sept. 4, 1996) (citing Voss, 450 N.E.2d at 207).

For example, if a car’s steering wheel—a simple machine—jams, prevents a user from steering, and results in an accident, the manufacturer would be strictly liable.48See Codling v. Paglia, 298 N.E.2d 622, 629 (N.Y. 1973). In this example, the manufacturer produced a car with a defective steering wheel, and the defect was a substantial factor in causing the car accident.49Id. The steering wheel did not act in the manner designed and intended by the manufacturer. If the user drove the car in a normal manner and would neither have discovered the defect nor perceived its danger, the court could find the manufacturer liable.50Id.

2. User Liability for Simple-Machine Torts

Users of simple machines may also be defendants for simple-machine torts if they own or use the simple machine in a negligent manner, and the machine causes injury to an innocent party.51See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1331. Users may be held partially or fully responsible for harms caused by simple machines.52Id. Under a negligence theory, courts may hold a user liable for harms to an innocent third party if the user violates a duty of reasonable care owed to that third party.53Id. at 1330. The “proper use of a machine or tool is embedded within the idea of a duty of care.”54Id. at 1331. People must act reasonably, even if they are assisted by machines and tools to do their tasks.55Id. For example, if a user buys a car and drives the car at reckless speeds and crashes into another car, the user of the car cannot blame the manufacturer because the driver operated the vehicle inappropriately.56John Villasenor, Products Liability Law as a Way to Address AI Harms, Brookings (Oct. 31, 2019), https://perma.cc/YF4T-CVZM.

If the user is the harmed party, the court still has to decide whether the manufacturer’s product was “modified after it left [the manufacturer’s] hands in a way which substantially altered [the product], and whether this modification was the proximate cause of [the user’s] injuries.”57Kromer v. Beazer East, Inc., 826 F. Supp. 78, 78, 80 (W.D.N.Y. 1993). If the user modifies the machine and tampers with the machine’s safety features, the court will likely find that even if the material alteration was foreseeable, the manufacturer cannot be responsible.58Id. at 81–82. Thus, a manufacturer would not be held liable for cases where the user directly modifies the simple machine because but for the user’s modification, there would have been no injury.59Id.; see also Lopez v. Precision Papers, Inc., 484 N.Y.S.2d 585, 587 (N.Y. App. Div. 1985), aff’d, 492 N.E.2d 1214 (1986).

B. Intelligent-AI Machines and Liability for Intelligent-AI Machine Torts

Technology has advanced past simple machines, and legal scholars have questioned how AI will fit into the existing tort system.60See Lawrence B. Solum, Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligences, 70 N.C. L. Rev. 1231, 1267 (1992). Humans no longer operate machines with remotes and buttons; instead, humans rely on AI to help them perform tasks.61Selbst, supra note 18, at 1319. AI is an umbrella term for computer programs that complete tasks that once required human intelligence to complete.62Van Duin & Backhshi, supra note 10. AI allows computers to “sense,” “reason,” “engage,” and “learn” using robotics, computer vision, voice recognition, natural language processing, or other technical features.63Id. Currently, legal scholars disagree on a singular definition of AI, and the term has been used to refer to a wide range of computer technology.64See Stephen McJohn & Ian McJohn, Fair Use and Machine Learning, 12 Ne. U. L. Rev. 99, 104–05 (2020). AI can refer to the non-physical software used by programmers to carry out tasks and also to the physical machines that use AI software.65Bryan Casey & Mark A. Lemley, You Might be a Robot, 105 Cornell L. Rev. 287, 297 (2020).

Advanced forms of AI use machine learning to not only carry out tasks coded by programmers but also decide inductively by referencing real-world data.66Horst Eidenmuller, Machine Performance and Human Failure: How Shall We Regulate Autonomous Machines?, 15 J. Bus. & Tech. L. 109, 112 (2019). For example, suppose a programmer wanted the AI to identify a cat. The machine would learn by “show[ing] the computer thousands of photos of cats, rather than write instructions telling the computer to look for cat-like features, such as whiskers and a tail. If AI misclassifies a fox as a cat, [the programmer can] show [the computer] more photos of cats” without editing the computer’s code. Sword, supra note 12, at 213. Like the human brain that uses neuron networks, machine-learning AI learns by connecting thousands of layers of data together to create images, rationalize outcomes, and make choices.67See David Silver, Thomas Hubert, Julian Schrittwieser & Demis Hassabis, AlphaZero: Shedding New Light on Chess, Shogi, and Go, DeepMind (Dec. 6, 2018), https://perma.cc/F3QG-HCNL; see also Casey & Lemley, supra note 65, at 323. Machine learning AI can thus develop its behavior over time by referencing new data and learning from its success and mistakes.68Kowert, supra note 22, at 183. This causes issues for manufacturers of machine-learning AI because they cannot predict what the machine will learn and how the machine will act in new situations.69Id. The lack of predictability raises concern among scholars who think that AI actions amount to “superseding causes” that prevent human counterparts from bearing the liability of the AI harm.70Id. Applying tort law to AI harms therefore leads to significant challenges.71Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1154. Legal scholarship attempts to assess who is liable for intelligent-AI torts by using simple machine analyses. Legal scholars discuss liability against the manufacturer of the AI, the user of the AI, or the AI itself.72See Glancy, supra note 28, at 657; Sword, supra note 12, at 226. The following discussion summarizes key arguments for and against imposing liability on these actors when intelligent-AI machines cause harm.

1. Manufacturer Liability for Intelligent-AI-Machine Torts

Plaintiffs injured by intelligent-AI machines may sue the manufacturers that design and produce the intelligent AI.73See Glancy, supra note 28, at 657. A majority of state courts may use the current strict liability for product liability claims against manufacturers for producing defective AI.74Id. at 658 (“[S]tates would apply strict liability rather than negligence to products liability claims for injuries and damages caused by a defective autonomous car.”). Scholars argue, however, that using the current product liability doctrine to hold manufacturers accountable for AI machine harms will cause negative consequences.75Sword, supra note 12, at 226. The first criticism against using traditional products liability is that manufacturers lack the capacity and foresight to program the intelligent-AI machine to avoid all situations that might result in harm.76Id. AI behaves unpredictably, and while the AI may reach the goals that the programmer asked for, programmers cannot understand how the AI reached that goal.77Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1147. Machine-learning technology has advanced to where the machines are constantly learning like human beings.78Id. at 1148. AI tort cases therefore include AI actions that are unforeseeable and AI harms that are unforeseeable.79Id. at 1153. Tort law cannot account for the vast range of actions and resulting harms that result from AI decisions.80Id. at 1144. Who should be responsible if an AI personal assistant discloses an individual’s private and sensitive medical, financial, and other personal data to a third party without the individual’s consent?81Id. at 1149. Who should be responsible if an AI security system mistakes a person for a burglar and traps the person inside the house, leading to false imprisonment claims?82Id.

A second criticism by scholars is that strict liability against manufacturers would discourage beneficial AI innovation.83See Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1164; Magnuson, supra note 9, at 379. Recently, there has been bipartisan agreement from the U.S. executive branch on the beneficial qualities AI offers society, and there has been support for the general innovation of AI.84See Exec. Order No. 13,859, 84 Fed. Reg. 3967, 3967 (Feb. 11, 2019) (exemplifying the executive’s treatment of AI under President Trump). President Biden also launched the National Artificial Intelligence (AI) Research Resource Task Force in June of 2021 to “promote AI innovation and fuel economic prosperity.” Press Release, The White House, The Biden Administration Launches the National Artificial Intelligence Research Resource Task Force (June 10, 2021), https://perma.cc/68TS-4P3J. Executive Order 13,859 titled “Maintaining American Leadership in Artificial Intelligence” encourages the U.S. to be a leader in “technological breakthroughs in AI” to “promote scientific discovery, economic competitiveness, and national security.”85Exec. Order No. 13,859, 84 Fed. Reg. at 3967. The Order indicates the U.S. government’s understanding that AI will become a huge driver of economic and national security, and that private industries and the market for AI technology should be encouraged and promoted.86Id. The restrictions that strict tort liability places on AI manufacturers lead some scholars to support a reformation of tort law to ensure that the U.S. is “more competitive in the world market” and that “innovation in product development” should be enhanced.87Hubbard, supra note 24, at 476. Strict liability for manufacturers may be overburdensome and prohibit new AI startups from entering the market, thus stifling innovation.88Id. at 452, 476. Since AI is intended to reduce accidents and human error, the chances of strict liability falling on manufacturers are low,89See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1325–26. so scholars still disagree on whether strict liability would prevent manufacturers from creating useful AI for the public.90Id.; Hubbard, supra note 24, at 476–77.

2. User Liability for Intelligent-AI-Machine Torts

Beside manufacturers, users also influence AI because they play a large role in shaping how and under what circumstances the AI learns.91See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1331. One scholar argues that if most subsets of AI technology require user interaction, the relevant tort analysis would be in negligence liability instead of products liability for manufacturers.92Id. at 1319, 1328. The first criticism against negligence liability for such harms is that a lack of foresight for AI decisions affects the application of negligence liability for AI harms because user defendants cannot be responsible for torts that they could not foresee or prevent.93Id. at 1322. A second criticism against imposing negligence liability on a user stems from the user’s dependency on the manufacturer’s warnings and instructions; thus a user who follows inadequate warnings and instructions should not be liable.94Id. at 1328. A third criticism argues that users will likely not be a factor in the assessment of liability for AI harms because the user is not using the AI in the same way a person uses a simple machine as a tool.95Id. (citing Gary E. Marchant & Rachel A. Lindor, The Coming Collision Between Autonomous Vehicles and the Liability System, 52 Santa Clara L. Rev. 1321, 1326 (2012)).

In addition to traditional negligence theories, courts may hold users liable for negligent supervision of the AI.96Id. at 1329 (citing F. Patrick Hubbard, “Sophisticated Robots”: Balancing Liability, Regulation, and Innovation, 66 Fla. L. Rev. 1803, 1861 (2014)). Would users of machine-learning AI be required to take responsibility for the machine they own like they would a pet or a child? This leads to issues in principal-agent law.97See Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1151. Machines that use AI technology “disrupt the idea of agency and the involvement of human beings.”98Id. at 1143. Establishing an agency relationship is a precondition to holding principals responsible for the acts of their agents.99See id. at 1144. Liability can only be imposed on a person who has the capacity “to act as a purposive agent.”100Id. at 1150. The Restatement (Second) of Torts designates an “actor” as “either the person whose conduct is in question as subjecting him to liability toward another, or as precluding him from recovering against another whose tortious conduct is a legal cause.”101Restatement (Second) of Torts § 3 (Am. L. Inst. 1965); see also Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1150. The problem is that AI machines are not “persons.” Thus, it is difficult to determine whether a principal-agent relationship exists,102See Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1151. particularly in cases where “no human being could be considered the principal behind the AI-robot acts.”103Id. at 1152.

3. Machine Liability for Intelligent-AI-Machine Torts

While some may find granting legal personhood to AI to be premature,104See, e.g., Yoon Chae & Ben Kelly, Granting AI Legal Personhood Would be Premature, Law360 (May 24, 2019, 12:58 PM), https://perma.cc/GVL7-ECVA. such views may change in light of the recent treatment of AI. For example, in 2014, a venture capital firm put an AI machine on its board of directors, and in 2017, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to Sophia the humanoid AI robot.105Id. At the moment, the existing structure of tort law does not apply liability to the AI machines.106Sword, supra note 12, at 230–31. That being said, some scholars have called for granting “legal personhood” to the AI so that the AI is liable for its own mistakes.107Solum, supra note 60, at 1231. While holding legal personhood for non-human entities is not unprecedented,108For example, business corporations hold the status of legal persons. See Sword, supra note 12, at 230. the main risk of holding the machine directly liable is that machine liability fails to support the corrective justice goal of tort law.109See id. at 230–31. It is unclear how courts can punish AI machines or correct the AI machine’s future actions.110Id. at 231.

The first criticism against imposing liability on the AI itself is that injured parties may not feel satisfied with assigning liability to the AI machine.111Id. While the machines may have intelligence, they currently lack the ability to have feelings or any type of emotional awareness (i.e., to feel guilty, remorseful, or morally obliged to do better in the future).112Elizabeth Fuzaylova, War Torts, Autonomous Weapon Systems, and Liability: Why A Limited Strict Liability Tort Regime Should Be Implemented, 40 Cardozo L. Rev. 1327, 1353–54 (2019). To satisfy an injured party’s desire for punishment, one scholar suggests potential punishments for machine harms could include requiring the AI’s owner to modify or monitor the AI, remove or disconnect the AI, or delete the AI altogether.113Dina Moussa & Garrett Windle, From Deep Blue to Deep Learning: A Quarter Century of Progress for Artificial Minds, 1 Geo. L. Tech. Rev. 72, 77 (2016) (citing Luciano Floridi & J.W. Sanders, On the Morality of Artificial Agents, 14 Minds & Machs. 349, 373 (2004)). These punishments, however, do not seem to incentivize better behavior on part of the AI.114See Sword, supra note 12, at 230–31. A second criticism is that there may also be a technological barrier that AI has yet to overcome before laws grant legal personhood to AI.115Moussa & Windle, supra note 113, at 78. Scholars have argued that AI must be able to do three things before it can be trusted to exercise reasonable care: react to novel changes of circumstance, exercise moral judgment, and exercise legal judgment.116Id. Scholars argue, however, that AI is currently incapable of executing this level of critical thinking.117Id. Thus, it is “incoherent to grant human rights to an artificial mind.”118Id. at 83.

The third criticism is that liability against the AI itself may disincentivize AI manufacturers from adequately testing the AI system, because the developers would not be liable for the AI’s harms.119Chae & Kelly, supra note 104. Such testing is fundamental to the “safe, functional, and cyber-secure” deployment of AI.120Rise of the Robots Brings Huge Benefits, but Also Creates New Loss and Liability Scenarios, Allianz Reports, The American Lawyer (Mar. 29, 2018). Ultimately, lack of testing and a competitive frenzy to bring new technology to the market would cause more dangerous and defective products to harm users or innocent third parties.121Id. Thus, multiple moral and legal barriers currently prevent courts from finding the AI liable for its own harms.122See Chae & Kelly, supra note 104.

Legal scholars have various ways of dealing with the question of who should be held liable when an intelligent-AI machine causes harm, and such assessments do not always align with the current simple machine liability found in traditional tort law cases. While the legal discourse may provide some guidance for courts in future intelligent-AI-harm cases, the general answer to the question of who should be held liable for such harms is unclear. Part II will explain how a succinct division of all intelligent-AI machines into automated- and autonomous- AI cases can help clarify the legal discussion surrounding AI liability.

II. Categorizing Intelligent-AI Machines and Assessing Liability for AI Torts

By using the words “AI,” “autonomous machine,” and “automation” as interchangeable synonyms,123Cf. Dave Evans, So, What’s the Real Difference Between AI and Automation?, Medium (Sept. 26, 2017), https://perma.cc/4QPY-PVS2. legal scholars overcomplicate the assessment of fault in intelligent-AI-machine-tort discussions. Some legal scholars have attempted to categorize intelligent-AI machines into further categories depending on autonomy. For example, one scholar separates “decision-assistance” AI that makes recommendations to users from fully-autonomous AI that makes decisions for itself.124Selbst, supra note 18, at 1319. Another scholar categorizes AI as either “knowledge engineering” AI that follows pre-programmed tasks from “machine learning” AI that learns and processes data to make decisions.125McJohn & McJohn, supra note 64, at 106. The National Highway and Traffic Safety Administration (“NHTSA”) uses five levels of classification for autonomy: fully manual cars; partially automated cars; automated cars; semi-autonomous cars; and fully-autonomous cars.126Selbst, supra note 18, at 1327; Nat’l Highway Traffic Safety Admin., supra note 18, at 9. This Comment adopts the terminology used in the autonomous vehicle context127Id. to separate intelligent-AI machines into two categories: automated-AI or autonomous-AI machines.128See Glancy, supra note 28, at 640. Using this distinction, courts can improve their assessment of liability and name the correct party responsible for the AI harm.

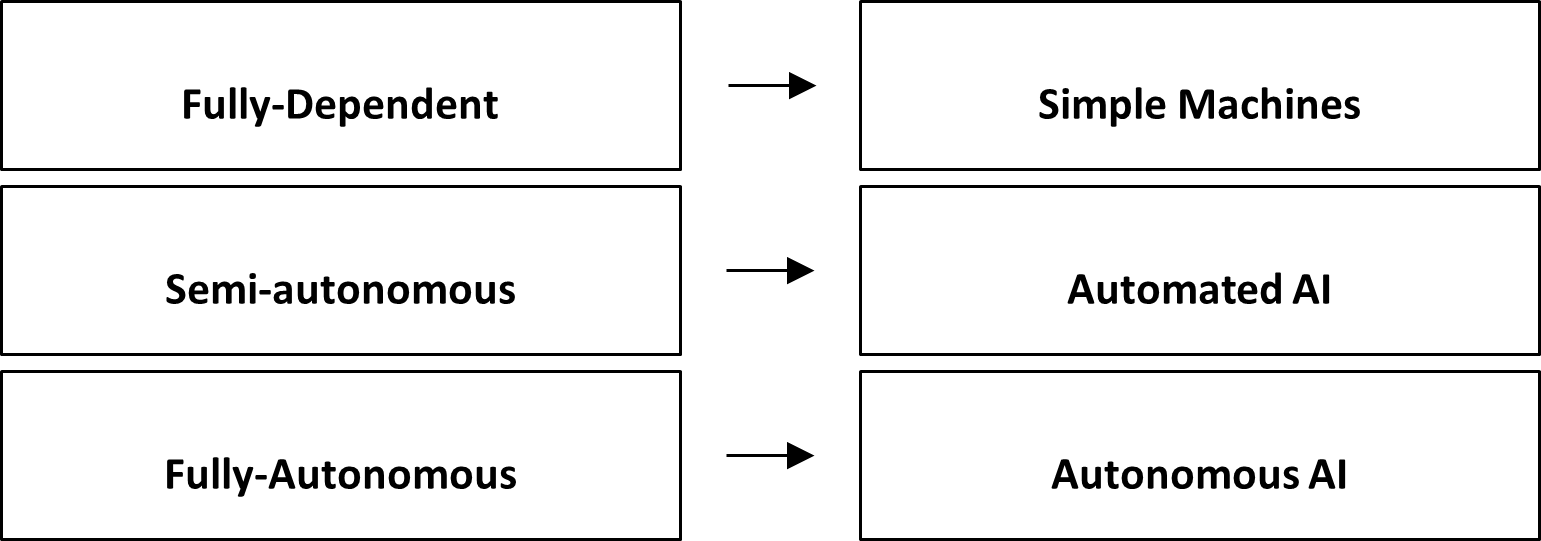

A. The Difference Between Automated AI and Autonomous AI and Why the Distinction Matters

Distinguishing automated-AI torts from autonomous-AI torts allows courts to separate the “easy” cases from the “difficult” ones. The discussion surrounding who should be liable for an intelligent-AI machine’s tort is complex because AI machines are not one homogenous group.129Selbst, supra note 18, at 1319. AI machines range from semi-dependent to fully-autonomous machines with varying complexities. This Comment attempts to simplify the legal scholarship of AI by categorizing machines as (1) fully-dependent, simple machines, (2) semi-autonomous, automated AI, or (3) fully-autonomous AI. Figure 2 summarizes the hierarchy of autonomy in machines.

Figure 2: Hierarchy of Machine Autonomy

Automated AI differs from autonomous AI. Automated AI follows pre-programmed, human instructions.130Harry Surden & Marry-Anne Williams,Technological Opacity, Predictability, and Self-Driving Cars, 38 Cardozo L. Rev. 121, 132 n.46 (2016). Automated AI requires manual configuration, so the system’s code is derived from various “if A, then B” statements.131Evans, supra note 123. For example, a user or programmer could set a smart thermostat with instructions like, “If it is hotter than seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit, turn the cooling unit on.” When the system detects the temperature has risen above seventy-five degrees Fahrenheit, the automated AI will thus start the home’s cooling unit.132See Jennifer Pattison Tuohy, The Best Smart Thermostat, N.Y. Times (Oct. 12, 2021), https://perma.cc/RP2R-YLN7. Examples of other automated AI include the capability of a car to parallel park on its own,133Jeanne C. Suchodolski, Cybersecurity of Autonomous Systems in the Transportation Sector: An Examination of Regulatory and Private Law Approaches with Recommendations for Needed Reforms, 20 N.C. J.L. & Tech. 121, 123 (2018). current online fraud detection systems for financial transactions,134See IBM Financial Crimes Insight for Entity Research, IBM, https://perma.cc/99RS-U8K4. and even Apple’s Siri.135See Erik Eckel, Apple’s Siri: A Cheat Sheet, TechRepublic (June 9, 2021, 7:16 AM), https://perma.cc/FXY7-DDRE.

Autonomous AI, on the other hand, can respond to real-world problems without any human intervention or direction.136Jason Hoffman, Autonomous vs. Automatic Robots: Know the Difference, WisdomPlexus, https://perma.cc/2K52-D2XZ. Autonomous AI systems heavily rely on machine learning, a subset of AI where the system learns and makes decisions inductively by referencing large amounts of data.137Eidenmuller, supra note 66, at 112; see also Sword, supra note 12, at 213. In machine learning, solutions to problems are not coded in advance. For example, Google created an advanced AI machine learning software that can play computer games like Go,138McKinsey & Company, An Executive’s Guide to AI, 12 (2020), https://perma.cc/SZ5F-4PSJ. Go is an intellectual board game like chess that requires players to test their analytical skills. A game of Go is described as being like playing four chess games on the same board. Why is Go Special?, British Go Association (Oct. 26, 2017), https://perma.cc/F33S-55BX. chess, and Shogi.139McKinsey & Company, supra note 138, at 12. Shogi is a Japanese board game that is also similar to playing Chess that requires critical thinking to successfully play. How to Play Japanese Chess Shogi, AncientChess.com, https://perma.cc/S23U-GGEY. The Google AI received no instructions from human experts and learned to play Go from scratch by playing itself.140Silver et al., supra note 67. In machine learning, “instead of deriving answers from rules and data, rules are developed from data and answers.” Eidenmuller, supra note 66, at 113. The AI could play millions of games against itself and learn through trial and error within hours.141Silver et al., supra note 67; see also Moussa & Windle, supra note 113, at 75 (“Deep learning is not only learning, but in some sense choosing what to learn.”). The machine did this using deep learning, a subset of machine learning based on “neural networks” that function similar to a human brain. Silver et al., supra note 67. After each game, the program adjusted its parameters.142Silver et al., supra note 67. Since the program was “unconstrained by conventional wisdom,” the program actually developed its own intuitions and strategies that its human counterparts could not even fathom.143Id. Humans may have assigned the autonomous-AI tasks, but the system chooses the means of performing the tasks.144Abbott, supra note 19, at 23. Those means—the choices and judgments the system makes—cannot be predicted by users or manufacturers assigning tasks or programming the original system.145Id.

Because intelligent-AI machines are not infallible,146John Villasenor, Products Liability Law as a Way to Address AI Harms, Brookings (Oct. 31, 2019), https://perma.cc/K9QQ-YX3H (“Given the volume of products and services that will incorporate AI, the laws of statistics ensure that—even if AI does the right thing nearly all the time—there will be instances where it fails.”). subsequent harms will occur eventually. An automated AI harm may look like an accident by a driverless car that fails to see an obstruction because the sensor could not recognize the object.147See Rebecca Heilweil, Tesla Needs to Fix Its Deadly Autopilot Problem, Vox (Feb. 26, 2020, 1:50 PM), https://perma.cc/5TGY-4HHC. An autonomous AI harm may look like discriminatory treatment based on a biased algorithm used to evaluate mortgage applications that considers “impermissible factors,” like race.148Villasenor, supra note 146.

By distinguishing between automated and autonomous AI, courts can more accurately assess liability for intelligent-AI harms and further the goals of tort law. Legal scholars have confined themselves to assessing AI liability through the broad lens of the general intelligent-AI machine versus simple-machine distinction. This leads to varied discussions about the liability for AI harms because some scholars are actually referring to automated AI and others are actually referring to autonomous AI.149Jorgensen, supra note 15 (defining a vehicle that “can completely navigate its way through from a point to another without any assistance from a driver” as “completely automated”); Eidenmuller, supra note 66, at 111 (defining “autonomous machines” as “artifacts which are ultimately designed and built by humans to perform specific functions without human intervention”); Sword, supra note 12, at 214 (using terms like “AI technology” and “AI” to refer to machine learning capabilities of AI). Distinguishing between the two categories organizes the legal discussion surrounding AI and illustrates that automated-AI cases are easier to resolve and autonomous-AI cases are harder to resolve. Automated-AI cases are “easy” because courts can solve them using the same torts liability regime used for simple machines. Thus, in automated-AI tort cases, courts can assign fault to the manufacturer or user. Most tort cases in the present-day concern automated AI because autonomous AI is not yet common in society. Thus, a majority of AI tort cases can be resolved under the existing tort system. Autonomous-AI cases are “hard” because courts will have difficulty applying the simple-machine-tort liability to Autonomous-AI harms. The difficulty stems from the fact that simple-machine-tort liability does not account for the autonomous AI’s independent decisions.

B. Simple-Machine Liability Extends to Automated-AI Torts

For automated systems that use AI, the current products liability structure for simple machines can extend to the automated AI features. This has already been suggested in a Tesla crash case, where the AI system in the Tesla can be categorized as automated AI. In 2016, a user turned his Tesla’s autopilot feature on while driving on a highway and was killed when the vehicle could not detect a trailer crossing the road.150Niraj Chokshi, Tesla Autopilot System Found Probably at Fault in 2018 Crash, N.Y. Times (Apr. 18, 2021), https://perma.cc/9B5W-JC2D. The National Transportation Safety Board (“NTSB”) and NHTSA found that Tesla’s autopilot system had no defects, even though the autopilot system was a substantial factor in causing the crash.151Id. In 2017, another fatal accident occurred with a user of a Tesla autopilot feature.152Heilweil, supra note 147. The user was killed when the vehicle hit a concrete barrier at high speed.153Id. The NTSB investigated the crash, and found that Tesla’s autopilot system “failed to keep the driver’s vehicle in the lane,” and that the system’s “collision-avoidance software failed to detect a highway barrier.”154Chokshi, supra note 150. In both deadly crashes, the users relied on Tesla’s autopilot and were distracted watching a movie or playing a video game.155Id.; Heilweil, supra note 147. The NTSB called for Tesla to include more warnings for users who remove their hands from the steering wheel to maintain vigilance.156Chokshi, supra note 150.

Using the facts of the Tesla crashes, a hypothetical court could hold the manufacturer, Tesla, liable under a products-liability theory for the autopilot software because such software is in the category of automated AI. Tesla’s AI software is not fully autonomous.157See Glancy, supra note 28, at 629. If the system’s cameras and sensors were faulty and caused the vehicle to fail to detect an obstruction, the manufacturer could be held liable for the manufacturing defects. The manufacturer could also be liable for failing to warn the user about the dangers of removing hands from the steering wheel and not being attentive. This analysis extends not only to driverless cars but also other automated-AI systems that follow the manufacturer’s code and design. While the plaintiff still has the burden of showing the manufacturer is strictly liable, the examples demonstrate plausible causes of action against the manufacturer in these automated-AI cases. The basis of the injured party’s claims is that the automated-AI harms can still be traced back to a specific human design.

Courts may also hold users liable for automated-AI torts using simple-machine-tort theories. When doctors use a machine to decide whether to use a particular drug or start certain treatments, society still has an expectation that the doctor knows how to use the machines in a manner that meets the appropriate standard of care.158Selbst, supra note 18, at 1319. Courts could impose similar treatment on users of automated AI. Additionally, users could be liable for negligently using or interacting with the automated AI in a manner unforeseeable by the manufacturers. For example, a user may substantially modify a system’s AI capabilities “by tampering with datasets or the physical environment.”159Nicole Kobie, To Cripple AI, Hackers are Turning Data Against Itself, Wired (Sept. 11, 2018, 7:00 AM), https://perma.cc/EA8M-9F6Z. Users may interfere with the automated AI system’s software by refusing to update the software or hacking into the system to modify the automated AI’s capabilities.160Id.

Under contributory or comparative negligence theories, users may be liable if they modify the automated AI after the AI leaves the manufacturer’s hands.1611 Louis R. Frumer, Melvin I. Friedman & Cary Stewart Sklaren, Products Liability § 8.04[1]–[2] (Matthew Bender & Co., Inc. 2021). If the modification substantially alters the system and the modification is a proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injuries, the user would be responsible for the AI harm.162See id. § 8.04[2]. An example of such modification was carried out by a Tesla hacking group.163The group is known as the “root access” community. Fred Lambert, The Big Tesla Hack: A Hacker Gained Control Over the Entire Fleet, But Fortunately He’s a Good Guy, electrek (Aug. 27, 2020, 3:29 PM), https://perma.cc/USR7-VKN2. This group of Tesla users hacked their cars “to get more control over them and even unlock unreleased features.”164Id. Manufacturers like Tesla could defend themselves by arguing that the automated-AI harm was due to the user’s modification and hacking of the vehicle code, not the manufacturer’s design, manufacture, or failure to warn.

By separating automated-AI cases from autonomous-AI cases, courts will find liability against a manufacturer or user without having to stray from the traditional tort law liability theories. Thus, if the injured party can trace the AI harm back to a human counterpart, judges will impose liability as if they were dealing with a simple machine.

C. Simple-Machine Liability Cannot Extend to Autonomous-AI Harms

While the automated-AI cases follow the traditional tort law theories, autonomous-AI cases do not. Legal scholars discuss AI as if they are fully autonomous, but most of the examples cited by these scholars, such as Tesla driverless cars, are automated AI, not autonomous AI.165German transportation regulators even wrote to Tesla asking Tesla to stop calling the feature “autopilot” because the term made the automated vehicle seem autonomous, thus causing drivers to overrely on the autopilot feature when the driver should have been attentive at all times. See Germany Tells Tesla: Stop Advertising ‘Autopilot’ Feature, DW Akademie (Oct. 17, 2016), https://perma.cc/PT9T-CCM6. Identifying automated AI with autonomous AI is misleading166Id. because automated AI only follows instructions and autonomous AI does not. Automated AI can be tied directly to human design, whereas autonomous AI can only be connected to human influence. For these reasons, it is difficult to impose simple-machine liability on autonomous-AI machines and systems. The following discussion explains this difficulty in detail.

1. Failure to Detect or an Error in Judgment?

Autonomous-AI harm is not caused by the system’s coded defect; rather, the harms stem from the system’s own error in judgment. The current structure of tort law may be able to place liability on a manufacturer for failure of an autonomous vehicle’s 3D censoring, radar, or high-tech camera failure, but liability for the system’s personal and uncoded decisions is less clear. Thus, legal scholars should be focusing on the truly autonomous cases as the main issue of AI liability, not automated-AI cases or intelligent-AI machines as a whole.

There is a difference between “failure to detect” cases of automated AI and “error in judgment” cases of autonomous AI. Imagine a classic “Trolley Problem” scenario.167The “Trolley Problem” is a philosophical thought experiment where a person conducting a runaway trolley is asked to choose between killing five people or flipping a switch and saving the five people, but killing one person. Bill Mordan, The Trolley Problem, ACC Docket (Sept. 1, 2016) https://perma.cc/EZ77-AXYR. If the Trolley had AI capabilities, a programmer of automated-AI trolleys could code the AI such that “if the trolley only has the option between hitting one person on the tracks versus five people on the tracks, the trolley should hit the one person.” The programmers would be the ones to make the initial judgment and justification of saving five people over one person. If the automated-AI trolley ends up in this situation, it would simply follow its code. If the automated-AI trolley does not follow the code, then the reason for its different decision is because of the machine’s failure to detect the outside world as it is—a problem with the machine’s manufactured component. If the automated-AI trolley does follow the code, then injured parties would know that the initial decision was precoded into the AI and a fault of the manufacturer.

In a fully-autonomous-AI-trolley problem, however, there is no “if-then” code to specify what the trolley should do. If the autonomous-AI trolley decides to hit the one person or the five people, the decision will be made through the autonomous-AI trolley’s own judgment, not manufacturer’s choice. Victims of the autonomous-AI trolley cannot trace their harms back to a specific manufacturer decision as concisely as with victims of automated AI. The autonomous-AI trolley does what it thinks is best based on learning from the real world. Maybe the autonomous-AI trolley chooses to hit the five people instead of the one. Maybe the trolley reasons that the five people were young and had a greater ability to survive a hit than an older person. It is less clear which type of liability to impose in this case. Imposing traditional products liability on manufacturers is inadequate because the manufacturer did not code the AI to act in this manner, and the physical components of the AI were not defective. Imposing negligence liability on users is inadequate because the trolley users had no superseding control over this autonomous-AI decision. Thus the application of traditional tort law liability is unclear for autonomous-AI harms.

2. Reduced Predictability for Manufacturers

Should a manufacturer of autonomous AI be liable for the harms caused by a machine it created years prior? If the AI learns and improves its abilities as time passes, the AI that the manufacturer initially designed may no longer be the same years later.168Sword, supra note 12, at 226. The manufacturers of autonomous AI cannot foresee how the AI will learn or decide in the same way they could foresee the decisions of automated AI.169Id. In automated-AI cases, manufacturers have more control and foresight over the actions that the automated AI may take. Using the simple-machine-tort-liability theories against manufacturers of autonomous AI may result in negative consequences. For example, manufacturers might rely on their inability to predict the potential harms that their autonomous AI creates, and thus avoid liability by claiming that the AI system itself was not defective at the time the system left the manufacturer’s hands.170Id. at 226–27.

Autonomous-AI manufacturers have no input into the specific decisions that the AI will take and cannot predict what information the AI will learn from once the AI leaves the manufacturer’s hands.171Abbott, supra note 19, at 23 (“Autonomous computers, robots, or machines are given tasks to complete, but they determine for themselves the means of completing those tasks. In some instances, machine learning can generate unpredictable behavior such that the means are not predictable either by those giving tasks to computers or even by the computer’s original programmers.” (citations omitted)). Even if the manufacturers program the autonomous AI to perform certain tasks, the manufacturers may struggle to identify all the possible manners in which the autonomous AI will choose to perform the task.172Id.

To illustrate this issue, imagine a collegiate robotics competition in which students have to program a robot with the ability and goal of getting the most robotic sheep into its pen.173Luba Belokon, Creepiest Stories in Artificial Intelligence (AI) Development, Medium (Sept. 21, 2017), https://perma.cc/UD8T-FBFR; see also Bill McCabe, The Dark Side of AI, LinkedIn (Feb. 22, 2018), https://perma.cc/9QD6-23TZ. The students have no remote control over the machines, and the machines have to act on their own and strategize the best way to win the competition.174Belokon, supra note 173. Once the contest begins, the robots quickly move around to collect sheep.175Id. One robot throws one sheep into its pen and shuts the gate.176Id. The students are confused because the robot would need to add more sheep to the pen to win the competition.177Id. To the students’s surprise, the robot turns around and begins to destroy its robot competition.178Id. The robot had decided on its own that it did not need the most sheep, it only needed to immobilize its competition.179McGabe, supra note 173. This scenario highlights the issue with autonomous AI that are tasked with certain baseline goals, but use independent judgment to execute those goals to the detriment of others and in a manner unforeseen by its creators.

3. Problems of Causation

When a manufacturer codes automated AI to behave in a certain manner or the machine malfunctions due to design or manufacturing defects, a plaintiff has less difficulty showing that the causation of the harm is a result of human design or error.180Kowert, supra note 22, at 183. Causation is difficult to prove even in the simple-machine or automated-AI cases,181See Granillo v. FCA US Ltd. Liab. Co., No. 16-153, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 116573, at *32 (D.N.J. Aug. 29, 2016). In Granillo, the Plaintiff purchased a Jeep Cherokee that was equipped with automatic transmission software created by Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (“FCA”). Id. at *4–5. When the Plaintiff started to have problems with the transmission (random acceleration and deceleration), the FCA-certified technician inspected the vehicle and updated the transmission’s software. Id. at *7 After that, the transmission ended up shutting down and had to be completely replaced. Id. The new transmission continued to have defects such as sudden jerking. Id. Plaintiffs ultimately could not show that the software defects and the transmission defects were one and the same. Id. at *32. and proving causation only becomes more difficult in autonomous-AI cases.182See Kowert, supra note 22, at 183. Autonomous AI presents a difficulty because the AI is not just following code. The AI is making decisions on its own. Thus, causation from a specific human influence is more difficult to determine.183Iria Giuffrida, Liability for AI Decision-Making: Some Legal and Ethical Considerations, 88 Fordham L. Rev. 439, 448 (2019) (“If an AI system makes a prediction or a decision, especially without substantial human involvement or oversight, the issue will be by what standard we should determine liability when unacceptable harm occurs but its causation cannot be determined.”).

Autonomous AI “can be as difficult to understand as the human brain.”184Yavar Bathaee, The Artificial Intelligence Black Box and the Failure of Intent and Causation, 31 Harv. J.L. & Tech. 889, 891 (2018). Thus, the AI is often characterized as “black boxes” that are incapable of communicating why they made the decisions they did.185Id. at 891–92. Programmers may not be able to pinpoint why the autonomous AI made certain decisions because the AI analyzes incredibly large amounts of data in a matter of seconds.186Id. at 892–93. The “black box” of autonomous AI may hinder a plaintiff from proving causation because “evidence of causation . . . must be substantial” and must not “leave[] the question of causation in the realm of mere speculation and conjecture.”187Merrill v. Navegar, Inc., 28 P.3d 116, 132 (Cal. 2001) (citations omitted) (finding insufficient showing of causation between a manufacturer that advertised a semiautomatic weapon and the harm caused by an individual using a model of that weapon to kill eight people and wound six). The causal relationships between the manufacturer, user, and the machine’s final decisions “may simply not exist, no matter how intuitive such relationships might look on the surface.”188Cary Coglianese & David Lehr, Regulating by Robot: Administrative Decision Making in the Machine-Learning Era, 105 Geo. L.J. 1147, 1157 (2017). For plaintiffs to even begin the causation analysis, they must think about which defendant—the user or the manufacturer—had more control over the autonomous AI’s learning process.189See Selbst, supra note 18, at 1319–20. Problems may arise depending on how long each human actor had with the system and how much the system learned from either of the human actors.

In the autonomous AI context, plaintiffs may have increased difficulty connecting the harm to a human user when the manufacturers may have some responsibility for the AI’s actions, but it is unclear if the AI based its decisions on the manufacturer’s influence. For example, manufacturers use training data to test the AI and expose the AI to various real-world scenarios prior to releasing the AI to consumers.190See Robin C. Feldman, Ehrik Aldana & Kara Stein, Artificial Intelligence in the Health Care Space: How We Can Trust What We Cannot Know, 30 Stan. L. & Pol’y Rev. 399, 405 (2019) (discussing healthcare AI systems). A lack of “sufficient and representative” training data may result in the AI’s poor function or cause the AI to have biases toward certain persons and things.191Id. Training data biases can “perpetuate historical, negative stereotypes across race and gender.”192Audrey Boguchwal, Fighting AI Bias by Obtaining High-Quality Training Data, Sama (Feb. 4, 2020), https://perma.cc/9TZY-CK5K. Unless the plaintiff can pinpoint the final autonomous AI’s decision to the biased data, however, it is difficult to determine whether the AI’s biases occurred because of the training data or data obtained from the AI’s real world experience. The autonomous AI learns from both types of data, but the “black box” makes it unclear what influenced the AI the most.

There are some circumstances in which simple-machine-tort theories can extend to autonomous-AI cases. Hacking cases would be an example of this because hackers substantially modify the autonomous AI to override the AI’s decision-making capabilities and judgments. Thus, but for the hacking, there would be no harm. Such hacking cases are not unimaginable. Tesla CEO, Elon Musk, stated that someone hacking an entire fleet of autonomous Tesla vehicles could put an end to the company:

In principle, if someone was able to say hack all the autonomous Teslas, they could say—I mean just as a prank—they could say “send them all to Rhode Island”—across the United States . . . and that would be the end of Tesla and there would be a lot of angry people in Rhode Island.193Lambert, supra note 163.

What is less clear is how autonomous-AI users impact causation analyses by simply using the machine in a certain way rather than directly hacking into the machine. Deep-learning neural networks allow the AI to “essentially program[] itself” and learn from human users.194Michelle Sellwood, The Road to Autonomy, 54 San Diego L. Rev. 829, 837 (2017). If users negligently use the autonomous AI to perform tasks, but did not harm anyone at the time, the AI still learns from the negligent user’s behavior. At a future date, the autonomous AI may even choose to act negligently if it reasons that the negligent behavior will not cause harm again.

The autonomous AI may also negligently cause harm without knowing it. In 2016, Microsoft designed a Twitter bot to learn from its conversations with other Twitter users.195Abby Ohlheiser, Trolls Turned Tay, Microsoft’s Fun Millennial AI Bot, Into a Genocidal Maniac, Wash. Post (Mar. 25, 2016, 6:01 PM), https://perma.cc/64YK-BZDN. Due to “troll” tweets196A “troll is someone who posts offensive, divisive, or argumentative remarks” on Twitter and other social media platforms. Cheryl Conner, Troll Control: Twitter and Instagram Premier New Tools for Abusive Social Media Use, Forbes (June 30, 2018, 6:52 PM), https://perma.cc/5U2G-24AF. from various users spewing hate speech, the bot went from an innocent experiment to a racist and highly offensive tweeter.197Ohlheiser, supra note 195. The bot not only repeated what users said to it, but formulated tweets of its own after learning from the troll tweets.198Id. When a Twitter user asked the bot whether the Holocaust occurred, researchers were shocked to see the bot respond by tweeting, “it was made up” followed by a clapping hands emoji.199Larry Yudelson, Racist Robot Rebooted, JewishStandard (Mar. 31, 2016, 3:58 PM), https://perma.cc/W68A-X2NP. Microsoft quickly deleted the tweet, apologized for the bot’s tweets, and acknowledged that the company “do[es] everything possible to limit technical exploits but also know[s] [it] cannot fully predict all possible human interactive misuses . . . .”200Ohlheiser, supra note 195. If injured plaintiffs seeking to sue the bot were harmed by the bot’s Tweets, would they be able to prove that the troll Twitter user tweets caused the bot to say harmful speech? Would they be able to prove that Microsoft caused the bot to say harmful speech? Causation is much less clear if the autonomous AI learns from negligent users. From this discussion then, it becomes clearer that courts cannot solve autonomous-AI cases in the same way that simple-machine or automated-AI cases may be solved. Autonomous-AI cases require an insight into the AI’s judgments.

III. A Solution for Assessing Liability for Intelligent-AI-Machine Torts

Due to the difficulties of extending the existing simple-machine-tort doctrines to autonomous-AI harms, this Comment proposes that the court analyze intelligent-AI-machine harms on a case-by-case basis. The court must account for both the manufacturer’s responsibility for creating and initially training the autonomous AI and the user’s subsequent influence and use of the autonomous AI. Instead of requiring the courts to use bright-line rules that lead to misplaced liability, courts should adopt a balancing test to weigh certain factors to determine who will be held responsible.

A. Courts Should Adopt a Balancing Test to Assess Liability for Autonomous-AI Torts

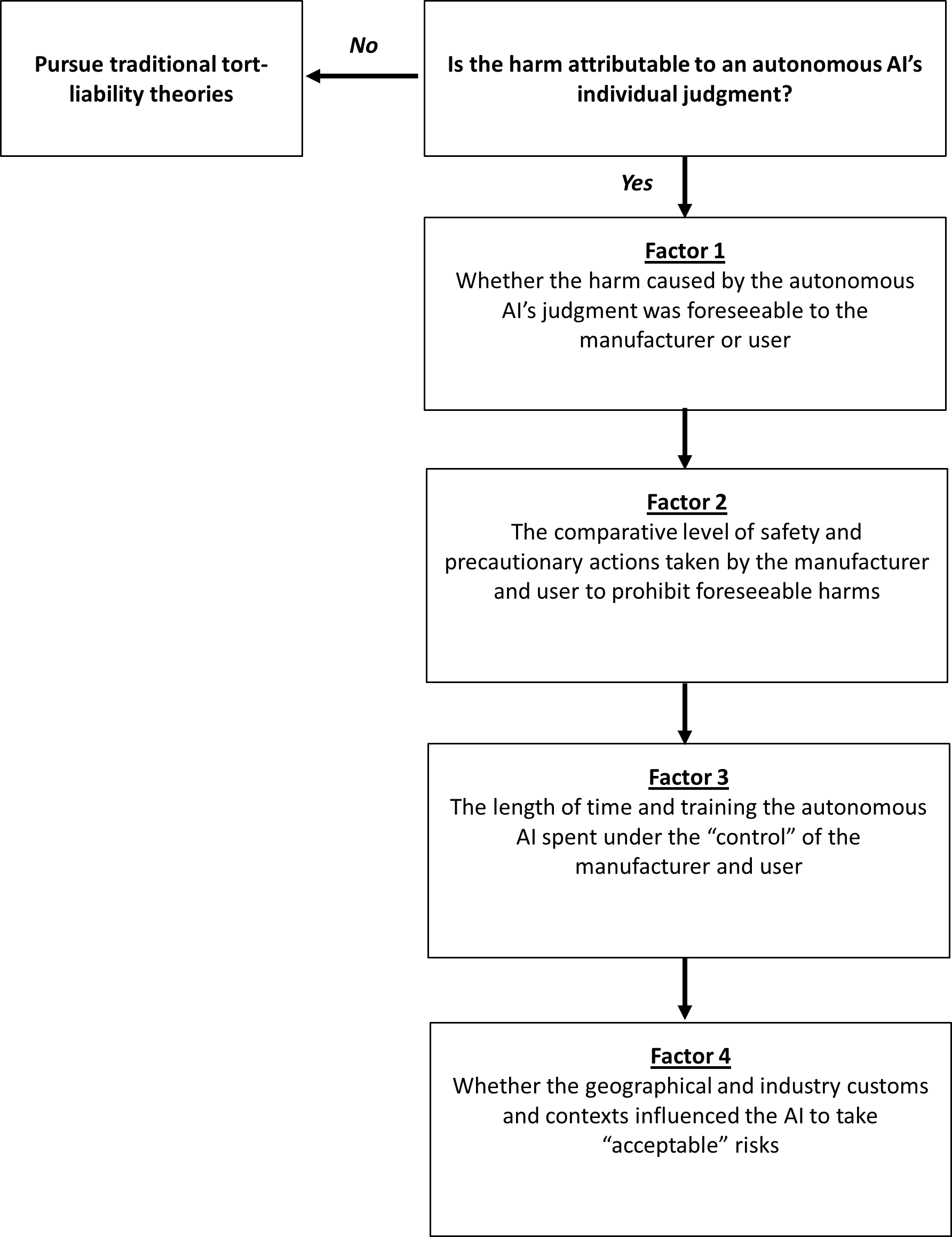

There are two steps to the balancing test. The first step is to determine whether the intelligent-AI harm is caused by automated AI or autonomous AI. If the harm is caused by automated AI, the court would determine whether the manufacturer or user, depending on the claim, is liable. If the autonomous AI caused the plaintiff’s injuries, the court will move forward with step two and weigh the balancing test factors: whether the harm caused by the autonomous-AI’s judgment was foreseeable; the comparative level of safety and precautionary actions taken by the manufacturer and user to prohibit foreseeable harms; the length of time and training the autonomous AI spent under the “control” of the manufacturer and user; and whether the geographical and industry customs and contexts influenced the AI to take “acceptable” risks. Figure 3 lays out this balancing test.

Figure 3: Balancing Test

1. Step One: Determine if the Harm was Caused by the Autonomous AI’s Own Judgment

Prior to weighing the factors in the balancing test, the court must first determine whether the harm was caused by an automated AI or autonomous AI. To do this, courts must ask whether the machine’s independent judgment caused the harm. If the AI’s failure to (a) detect information, or (b) act according to manufactured instructions caused harm, the manufacturer can be held liable under a products liability regime. Conversely, if a user hacks or modifies the AI, or uses the AI in an unsuitable and unreasonable manner, the user could be held liable under a negligence regime. Courts would handle these automated-AI cases as if it were an ordinary simple-machine-tort case.

If, however, defendants plead that the harm was caused by the machine’s own doing, the court must determine whether the fault is due to the machine’s individual judgment. The step one inquiry is necessary because there is a difference between humans directly programming a machine to act in a certain manner through code and design, and humans indirectly influencing a machine through manufacturing, training data, and user experiential data. For example, directing the AI to discriminate against third parties through code differs from introducing biased data that portrays certain characteristics as “bad” or failing to correct the AI when it chooses to discriminate against a third party.201See generally Feldman, supra note 190. Both influences cause harm, so the court must assess both. The direct influences are assessed under the existing simple-machine-tort-law doctrines. The indirect influences must be weighed by the proposed balancing test.

2. Step Two: Balance the Relevant Factors to Determine Liability

If the court determines that the fault is due to the autonomous AI’s individual judgment, the court must then weigh the following factors: (1) whether the harm caused by the autonomous AI’s judgment was foreseeable; (2) the comparative level of safety and precautionary actions taken by the manufacturer and user to prohibit foreseeable harms; (3) the length of time and training the autonomous AI spent under the “control” of the manufacturer and user; and (4) whether the geographic and industry customs and contexts influenced the AI to take “acceptable” risks.

The first factor does not ask users or manufacturers to dissect the “black box” of AI decisions to find which piece of data caused the machine to reason the way it did. Instead, courts will analyze whether the resulting harm was reasonably foreseeable by the manufacturer or user. If the harm was foreseeable, courts would expect that the defendant would take the necessary precautions. The second factor examines whether the user or manufacturer set up reasonable precautions to prevent any foreseeable harms. This factor incentivizes manufacturers to impose basic restrictions into the AI. Users may also reduce their responsibility if they take adequate precautions. Courts should compare the level of precautions taken by each defendant to assess whether a defendant could have reasonably done more to prevent foreseeable harms. Maybe both defendants took major precautions or the risk was highly unforeseeable. In the unforeseeable risk cases, the other factors would weigh more heavily than the second factor.

The third factor allows the judge to compare the relative influences that a manufacturer of a product and a user of a product had on the autonomous AI depending on the amount of time each actor spent with the autonomous AI. The court must account for cases where the user exerted influence over the AI for a long time, or cases where the harm occurred the day after the user purchased the machine. This Comment will not attempt to impose default rules for the amount of time a manufacturer or user needs to have asserted control to be liable. The time factor depends on the specific circumstances of the case and the type of AI technology involved at the time of the plaintiff’s injuries. For some autonomous AI, the AI might require months to form decisions of its own and create new actions and motives. For other autonomous AI with advanced machine learning or deep learning capabilities, it may only need hours to learn and start making decisions without the manufacturer’s training data.202See, e.g., Silver et al., supra note 67. The purpose of this test is to help courts adapt to the varying and evolving applications of autonomous AI liability.

The fourth and final factor ensures that judges consider how AI used in various geographic and industry contexts will result in AI behaving and acting in different manners and for different purposes. A hospital would use an autonomous-AI prescribing physician differently than a driver and her autonomous-AI vehicle or a business and its autonomous-AI financial advisor. Each industry has its own customs for standard of care and risk, so courts cannot analyze AI in varying industries in the same manner. Additionally, the type of data autonomous AI receives and learns from would be different depending on the geographical context. Autonomous-AI vehicles driving in a rural area may behave differently than autonomous-AI vehicles in urban areas. The court would thus have to look at the harm caused by the AI’s judgment and compare it to the industry and area customs and practices.203This Comment does not suggest that a reasonably prudent AI analysis takes the place of the reasonably prudent person analysis in autonomous-AI cases. The purpose of the fourth factor is to make sure courts do not analyze all autonomous-AI cases that have different tasks in different industries in the same manner. As autonomous-AI cases grow in the future, it may be preferable to organize the AI by industry and have separate standards of care for AI performing in each industry. For now, this Comment only suggests a general balancing test for autonomous AI.

3. Addressing Counter Arguments Against the Balancing Test

One counter argument to the balancing test is that it reduces efficiency and certainty in the courts as to who will be held liable.204Cf. Selbst, supra note 18, at 1326. Certainty overt tort liability for autonomous AI would look like laws that always impose liability on the manufacturer or always impose liability on the user. Injured parties would know which party to sue for damages. While this approach may save time and resources during the litigation stage, there are three reasons why a balancing test is preferable. First, a balancing test incentivizes good behavior on part of the defendant manufacturer or user. Second, a balancing test would not stifle the innovation of AI technology. Third, autonomous-AI cases currently make up a small minority of AI cases, and thus courts would not be required to balance factors for every single AI tort case.

Only assigning liability to the manufacturer may disincentivize the user from acting reasonably and vice versa. If the user is never liable, users will be more likely to negligently interact with the autonomous AI, and if the manufacturer is never liable, manufacturers will be less likely to create safety precautions.205See Kowert, supra note 22, at 199. If users were never held negligent for failing to listen to the autonomous car’s warnings to wear a seatbelt or recharge the car’s battery, and the user’s negligence seems to be a factual cause of harm, then it seems inconsistent to hold the manufacturer responsible. Strict liability against a single party might save the court time, but the court would be holding the wrong party responsible. Only imposing liability on the manufacturer or user also fails to account for the machine’s own judgment and places blame on a human party that had no control over the machine’s actions. The “Captain of the Ship” doctrine states that if a patient is harmed during the course of a surgical operation, the surgeon will be held liable for the actions of all the medical professionals who were present.206Sword, supra note 12, at 219. Courts reject this doctrine because the surgeon may not be responsible for the harms caused by a specific medical professional present during the operation.207Id. If autonomous AI replaces a human surgeon, it may be difficult for the law to impose liability on other human physicians in the room during surgery. The human physicians may have no control over the autonomous AI, and they may not make contributions towards the autonomous AI’s analysis that caused patient harm.208Id. at 220–21. Only assigning liability against one party does not always hold the correct party responsible, and thus lets other human actors be free riders. The balancing test proposed by this Comment, on the other hand, puts both manufacturers and users on notice that courts will acknowledge their influence over the autonomous AI. The balancing test also considers which party, if any, is responsible without burdening one party to take more precautions than the other.

Another criticism of the balancing test might be that “uncertain tort liability will hinder innovation.”209Selbst, supra note 18, at 1326. As discussed in Part I, however, strict liability would actually have a more detrimental impact on AI innovation.210See Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1164; Magnuson, supra note 9, at 379. The added uncertainty that the balancing test creates may foster the safe development of AI. If manufacturers think courts will always hold them strictly liable, no matter what safety features they implement, there may be a reluctance by manufacturers to invest into AI safety infrastructure when the cost of liability outweighs the benefits of implementing safety.211See Rachum-Twaig, supra note 11, at 1164. On the other hand, if users are always liable, this may disincentivize manufacturers from creating reasonably safe machines and working with the autonomous AI to develop reasonably accurate training data or baseline codes to protect human life. The balancing test encourages balanced behavior from human actors. Users and manufacturers who take precaution will know that the precaution would aid the assessment of their liability in court.