Introduction

This Term, in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo145 F.4th 359 (D.C. Cir. 2022), cert. granted, 143 S. Ct. 2429 (2023). and Relentless, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Commerce,262 F.4th 621 (1st Cir. 2023), cert. granted, 144 S. Ct. 325 (2023). the Supreme Court will expressly consider whether to overrule Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc.3467 U.S. 837 (1984).—a bedrock precedent in administrative law that a reviewing court must defer to a federal agency’s reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute that the agency administers.4See id. at 843–44; Brief for Petitioners at i, Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, No. 22-451 (U.S. July 17, 2023). In our contribution to this Chevron on Trial Symposium, we argue that the Court should decline this invitation because the pull of statutory stare decisis is too strong to overcome.

Over the last four decades, the Court has repeatedly reaffirmed Chevron, and the federal courts of appeals have relied on it in thousands of cases.5See infra Part I. Chevron has come to be understood as a judicial interpretation of the Administrative Procedure Act (“APA”).6Id. Congress has legislated against that Chevron backdrop and refused to enact numerous bills that sought to abrogate it.7See infra Section I.A. Indeed, Congress, federal agencies, the lower federal courts, and the public have all relied on Chevron.8See infra Section I.B. Moreover, the original understanding of the scope of judicial deference under the APA is at best muddled, and the constitutional arguments against Chevron are unpersuasive.

Chevron also has several normative justifications that bolster its status under stare decisis. Chevron advances rule-of-law values in the modern administrative state. Aside from the conventional values of agency expertise, enhanced deliberative process, and more politically accountable policymaking, our empirical scholarship sheds light on two less appreciated values.

First, Chevron encourages stability in federal law. Because the Court reviews only a fraction of the hundreds of judgments concerning administrative interpretations of law each year, judicial review of agency statutory interpretations rests mostly with the courts of appeals. Chevron reduces disagreements among federal courts over policy-laden judgments and thus promotes national uniformity. Our review of more than a decade of published courts-of-appeals decisions mentioning Chevron demonstrates a nearly twenty-five-percent point difference as to the prevailing rate of agency statutory interpretations, depending on whether a circuit court does or does not apply the Chevron framework. Under Chevron, an agency’s nationwide policy implementation of a statute it administers is more likely to govern, as opposed to a patchwork scheme of potentially conflicting judicial interpretations across the federal courts of appeals with ideologically disparate panels providing their “best readings” of the statute.

Second, the findings from our study underscore another significant and largely overlooked cost of eliminating Chevron: judges’ policy preferences would play a larger role in review of agency statutory interpretations. Our empirical work demonstrates that Chevron has, to a substantial degree, succeeded in removing judges from policy decisions that Congress has delegated to agencies. By doing so, it has promoted stability in judicial decisionmaking across ideologically varied courts of appeals, increasing national uniformity and predictability in federal law.

Finally, stare decisis should apply when the Court has otherwise addressed concerns over the challenged doctrine. In recent years, the Court’s approach to Chevron has already mitigated the concerns that the Loper Bright and Relentless petitioners and others raise. The Court has instructed lower courts to take Chevron step one seriously, precluding deference when the statute is “clear enough.”9See, e.g., Wis. Cent. Ltd. v. United States, 585 U.S. 274, 283 (2018). It has suggested that Chevron step two should be a meaningful check on unreasonableness, including whether the agency’s interpretation is impermissibly arbitrary and capricious. And, of course, the major questions doctrine precludes Chevron deference—or regulatory activity at all—when an agency seeks to regulate certain major policy questions without clear congressional authorization.

I. Chevron and Stare Decisis

Chevron has been settled law for nearly four decades.10Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 837 (1984). Westlaw reports that it has been cited in almost 100,000 documents in its databases, including in more than 18,000 federal court decisions.11Citing References of Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., Thomson Reuters Westlaw Precision, http://1.next.westlaw.com (results as of Feb. 13, 2024, found by navigating to Chevron opinion; then selecting “Citing References”). It remains the most cited administrative law decision of all time,12See, e.g., Peter M. Shane & Christopher J. Walker, Foreword, Chevron at 30: Looking Back and Looking Forward, 83 Fordham L. Rev. 475, 475 (2014). including in approximately seventy Supreme Court decisions.13See Brief for the Respondents at app. B, Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, No. 22-451 (U.S. Sept. 15, 2023) (listing Supreme Court decisions citing Chevron). It provides a framework for judicial review of agency interpretations of statutes that Congress has empowered those agencies to administer. Although the Chevron decision itself famously does not refer to the APA, it is understood as a judicially created doctrine designed to implement section 706 of the APA.14See, e.g., United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218, 227, 229 (2001) (referring to 5 U.S.C. § 706, in describing agencies’ interpretive primacy when Congress has delegated such interpretive authority to agencies). Indeed, Chevron is grounded on a theory of congressional delegation whereby courts defer to reasonable agency statutory interpretations to realize Congress’s explicit or implicit delegation when empowering an agency to administer a statutory scheme.15See Chevron, 467 U.S. at 843–44, 865–66.

As to judicial precedents interpreting statutes, “stare decisis carries enhanced force” because those who think the judiciary wrongly decided the issue “can take their objections across the street, and Congress can correct any mistake it sees.”16Kimble v. Marvel Ent., LLC, 576 U.S. 446, 456 (2015). In this “superpowered form of stare decisis,” the Court has required “a superspecial justification to warrant reversing” the statutory precedent.17Id. at 458. Indeed, the necessity for that justification “is even more than usually so” when, as with Chevron, (1) the Court would have “to overrule not a single case, but a ‘long line of precedents’—each one reaffirming the rest”; (2) that line of precedents “pervades the whole corpus of administrative law”; and (3) overruling Chevron “would allow relitigation of any decision based on” its framework.18Kisor v. Wilkie, 139 S. Ct. 2400, 2422 (2019) (quoting Michigan v. Bay Mills Indian Cmty., 572 U.S. 782, 798 (2014)).

Unlike constitutional stare decisis, statutory stare decisis is grounded in legislative supremacy. As then-Professor Amy Coney Barrett explained, this legislative supremacy rationale comprises two distinct strands: separation of powers and congressional acquiescence.19Amy Coney Barrett, Statutory Stare Decisis in the Courts of Appeals, 73 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 317, 322–27 (2005). The separation-of-powers strand addresses the concern that the legislature has greater institutional competence than the judiciary to revisit statutory precedents.20Id. at 323; see also id. at 323 nn.28–31 (collecting cases). Relatedly, when considering longstanding statutory precedents, “congressional inaction following the Supreme Court’s interpretation of a statute reflects congressional acquiescence in it.”21Id. at 322; see also id. at 322 n.23 (collecting cases).

The separation-of-powers concerns for Chevron are pronounced. As then-Professor Antonin Scalia observed, the Court has long respected “the APA as a sort of superstatute, or subconstitution, in the field of administrative process: a basic framework that was not lightly to be supplanted or embellished.”22Antonin Scalia, Vermont Yankee: The APA, the D.C. Circuit, and the Supreme Court, 1978 Sup. Ct. Rev. 345, 363. In enacting the APA, Congress established the ground rules for the relationships between the three branches of the federal government surrounding federal agency actions.23See, e.g., Christopher J. Walker & Scott T. MacGuidwin, Interpreting the Administrative Procedure Act: A Literature Review, 98 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1963, 1993 (2023). As one of us has argued elsewhere, “Settled statutory precedents interpreting that separation-of-powers framework statute should only be upset in extraordinary situations.”24Id.

The congressional acquiescence justification for statutory stare decisis is arguably stronger for the APA than for most statutes, due to the APA’s status as a superstatute or subconstitution for the modern regulatory state. Many of the key judicial precedents interpreting the APA, including Chevron, go back decades.25See, e.g., id. at 1963, 1966–89 (surveying statutory precedents). During this time, Congress has legislated against the backdrop of APA statutory precedents when it authorizes—and reauthorizes—the hundreds of statutes that govern federal agencies today, including when it has departed from that backdrop in countless statutes governing numerous federal agencies.26See infra Section I.A (discussing examples in the Chevron context). In a very real sense, Congress is reenacting the statutory scheme that the Court considered.27Cf. Bank of Am. Corp. v. City of Miami, 581 U.S. 189, 201 (2017) (“Principles of stare decisis compel our adherence to those [statutory] precedents in this context. And principles of statutory interpretation require us to respect Congress’ decision to ratify those precedents when it reenacted the relevant statutory text.”).

Beyond notions of separation of powers and inferred congressional acquiescence, reliance on Chevron is extremely strong—by Congress, congressional drafters, agency officials, and the public.

A. Chevron and Congressional Codification

Congress has strongly relied on Chevron as a background principle in drafting legislation and, at times, signaled its application or rejection. Although Congress rarely refers to Chevron by name, on occasion it has altered the standards of review for agency interpretations, including in some of its most monumental legislation,28See generally Kent Barnett, Codifying Chevmore, 90 N.Y.U. L. Rev. 1 (2015) (discussing how Congress has codified Chevron and Skidmore (“Chevmore”) and its meaning for Chevron’s delegation theory). and rebuffed attempts to abrogate Chevron via statute.

For instance, Congress modified Chevron’s application in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (“Dodd-Frank”), enacted to respond to the 2008 financial crisis.29See id. at 22–33. In that legislation, Congress rendered judicial review of certain preemption decisions of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) more searching by codifying the factors from Skidmore v. Swift & Co.,30323 U.S. 134 (1944). when Chevron otherwise would have applied.31See id. at 140; see also Barnett, supra note 28, at 28. Congress requires courts to “assess the validity of such [preemption] determinations, depending upon the thoroughness evident in the consideration of the agency, the validity of the reasoning of the agency, the consistency with other valid determinations made by the agency, and other factors which the court finds persuasive and relevant to its decision.”3212 U.S.C. § 25b(b)(5)(A). Congress included a savings clause to clarify that the more searching review of the OCC’s preemption ruling does not “affect the deference that a court may afford” other OCC interpretations.33Id. § 25b(b)(5)(B).

An accompanying Senate Report indicates that the senators understood that Chevron deference might apply to other OCC interpretations.34S. Rep. No. 111-176, at 176 (2010) (“Section 1044 clarifies that nothing affects the deference that a court may afford to the OCC under the Chevron doctrine when interpreting Federal laws administered by [the OCC], except for preemption determinations.”). The few remarks in the House on this topic indicate that members of the House shared the Senate’s understanding of Chevron as a background drafting principle.35See Barnett, supra note 28, at 28–29 (discussing legislative history). Dissenting senators did not contest the majority’s understanding of the preemption provisions; instead, they worried that the provisions’ effect would be to “eliminate[ ] preemption and . . . create significant legal uncertainty.”36S. Rep. No. 111-176, supra note 34, at 247 (discussing minority views of Senators Richard Shelby, Michael Bennett, James Bunning & David Vitter). In other words, Congress indicated in Dodd-Frank that it understood Chevron to be the background deference regime and signaled when it wanted, and did not want, Chevron to apply.

Indeed, Congress went even further in Dodd-Frank when it created the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (“CFPB”) and reallocated authority over consumer protection statutes among federal agencies.37See Barnett, supra note 28, at 34. Congress gave various agencies concurrent jurisdiction to enforce these statutes.38See id. at 32. In doing so, Congress appeared aware of a longstanding debate as to whether Chevron deference is available when more than one agency is charged with administering a statutory scheme.39See id. at 32–33.

For some of the statutory schemes, Congress provided that

the deference that a court affords to the Bureau with respect to a determination by the Bureau regarding the meaning or interpretation of any provision of a Federal consumer financial law shall be applied as if the Bureau were the only agency authorized to apply, enforce, interpret, or administer the provisions of such Federal consumer financial law.4012 U.S.C. § 5512(b)(4)(B); see also 15 U.S.C. § 1604(h) (establishing a similar provision in the Truth in Lending Act).

This provision’s apparent purpose is to ensure that the CFPB receives Chevron deference for relevant interpretations, even if courts would normally presume that Congress would not delegate interpretive primacy to an agency when other agencies also administer those statutes.41See Barnett, supra note 28, at 32–33. In other instances, Congress instructed courts to treat each administering agency as if it were the only administering agency, presumably to render Chevron deference available for each agency’s interpretations.42See, e.g., 15 U.S.C. § 1681s(e)(2) (Fair Credit Reporting Act); 15 U.S.C. § 1691b(g) (Equal Credit Opportunity Act).

Congress has also signaled in at least two other instances when it does not want courts to defer to agency statutory interpretations. Congress, again in Dodd-Frank, instructed the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit not to defer to the Commodities Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission on certain rules and orders.4315 U.S.C. § 8302(c)(3)(A) (instructing the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit to “give deference to the views of neither Commission”). Likewise, in a provision concerning federal preemption of insurance regulation, Congress has instructed that courts review “the merits of all questions presented under State and Federal law, including the nature of the product or activity and the history and purpose of its regulation under State and Federal law, without unequal deference.”4415 U.S.C. § 6714(e) (emphasis added).

Congress has not only legislated with Chevron in mind, but it has also consistently refused to abrogate Chevron. When rejecting a call to overrule Auer deference, the Court found it relevant that—as here, with Chevron—Congress refused to act despite the Court’s “deference decisions reflect[ing] a presumption about congressional intent” and despite “[m]embers of this Court . . . rais[ing] questions about the doctrine.”45Kisor v. Wilkie, 139 S. Ct. 2400, 2422–23 (2019) (first citing Martin v. Occupational Safety and Health Rev. Comm’n, 499 U.S. 144, 151 (1991); and then citing Talk Am., Inc. v. Mich. Bell Tel. Co., 564 U.S. 50, 67–69 (2011) (Scalia, J., concurring)). Congress has refused over approximately forty years to enact numerous bills that sought to abrogate Chevron.46See, e.g., Regulatory Accountability Act of 2017, H.R. 5, 115th Cong. § 202 (2017); Separation of Powers Restoration Act, S. 909, 116th Cong. § 2 (2019); Separation of Powers Restoration Act of 2023, H.R. 288, 118th Cong. § 2 (2023); Elizabeth Garrett, Legislating Chevron, 101 Mich. L. Rev. 2637, 2660–61 (2003) (discussing the Bumpers Amendment, which failed to pass in the 1970s and early 1980s). Indeed, when recent bipartisan support in the Senate for modernizing the APA arose, the sponsoring senators left Chevron deference undisturbed, while replacing Auer deference for agency regulatory interpretations with the less deferential Skidmore standard.47See Christopher J. Walker, Modernizing the Administrative Procedure Act, 69 Admin. L. Rev. 629, 667–69 (2017) (discussing the Portman–Heitkamp Regulatory Accountability Act, S. 951, 115th Cong. § 4 (2017)). As the government noted in its brief in Loper Bright, Congress has heard from consumer, faith, and labor groups who have opposed abrogating Chevron because its absence would empower the judiciary.48Brief for the Respondents, supra note 13, at 30 (citing H.R. Rep. No. 114-622, at 21 (2016)). In other words, Congress has been apprised of the policy choice that is inherent in choosing a deference regime and has stuck with the status quo.

Although judicial deference may not be the stuff that excites certain elements of governing coalitions, Chevron is no political backwater. Overruling Chevron was a plank of the Republicans’ 2016 platform that propelled President Trump to office,49See Republican Nat’l Convention, Republican Platform 2016, at 10 (“We further affirm that courts should interpret laws as written by Congress rather than allowing executive agencies to rewrite those laws to suit administration priorities.”). and the current House of Representatives with a Republican majority has passed a bill that would abrogate Chevron.50H.R. 288, § 2. The fact that the Senate with its super-majority voting rules refused to pass the House’s bill—as is true for numerous other Democratic and Republican legislative efforts alike—is of no moment. Moreover, Florida51Fla. Const. art. V, § 21 (“In interpreting a state statute or rule, a state court or an officer hearing an administrative action pursuant to general law may not defer to an administrative agency’s interpretation of such statute or rule, and must instead interpret such statute or rule de novo.”). and Arizona52Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 12-910(F)–(G) (2016) (limiting judicial deference to agency legal interpretations “[i]n a proceeding brought by or against the regulated party” concerning all but one agency). have, outside of the judicial branch, abrogated or refined their forms of the Chevron doctrine, demonstrating that abrogating Chevron is far from a political impossibility.

To be sure, Congress has also not enacted proposals to codify Chevron.53H.R. 6107, 117th Cong. § 11 (2021); S. 343, 104th Cong. § 5 (1995). But its failure to do so provides little insight to congressional intent. Congress has little reason to codify that which is already the law. Moreover, Congress may have some concern over the unintended consequences of upsetting the status quo or development of the doctrine (whether by codifying or abrogating Chevron), leading it to take more refined action in specific contexts.54See Garrett, supra note 46, at 2661.

Contrary to concerns from past and current members of the Court, Congress’s understandings, practice, and knowing acceptance of Chevron demonstrate that Chevron’s undergirding theory—that Congress seeks to delegate interpretive primacy to agencies over statutory ambiguities in statutes that agencies administer—is not “fictional,” regardless of whether Chevron correctly inferred congressional intent when it was decided.55See David J. Barron & Elena Kagan, Chevron’s Nondelegation Doctrine, 2001 Sup. Ct. Rev. 201, 212 (“Because Congress so rarely makes its intentions about deference clear, Chevron doctrine at most can rely on a fictionalized statement of legislative desire, which in the end must rest on the Court’s view of how best to allocate interpretive authority.”); Stephen Breyer, Judicial Review of Questions of Law and Policy, 38 Admin. L. Rev. 363, 370 (1986) (referring to Chevron’s delegation theory as a “legal fiction”); Antonin Scalia, Judicial Deference to Administrative Interpretations of Law, 1989 Duke L.J. 511, 517 (“[A]ny rule adopted in this field [such as Chevron] represents merely a fictional, presumed intent, and operates principally as a background rule of law against which Congress can legislate.”).

B. Chevron and Settled Expectations

Beyond codifying Chevron or Skidmore with respect to specific regulatory schemes and refusing to abrogate Chevron by statute, Congress and its legislative drafters rely heavily on Chevron as a background statutory drafting and interpretive rule. The same is true for federal agencies when interpreting statutes and drafting regulations, and for federal courts and the public when interpreting and interacting with statutes that federal agencies administer.

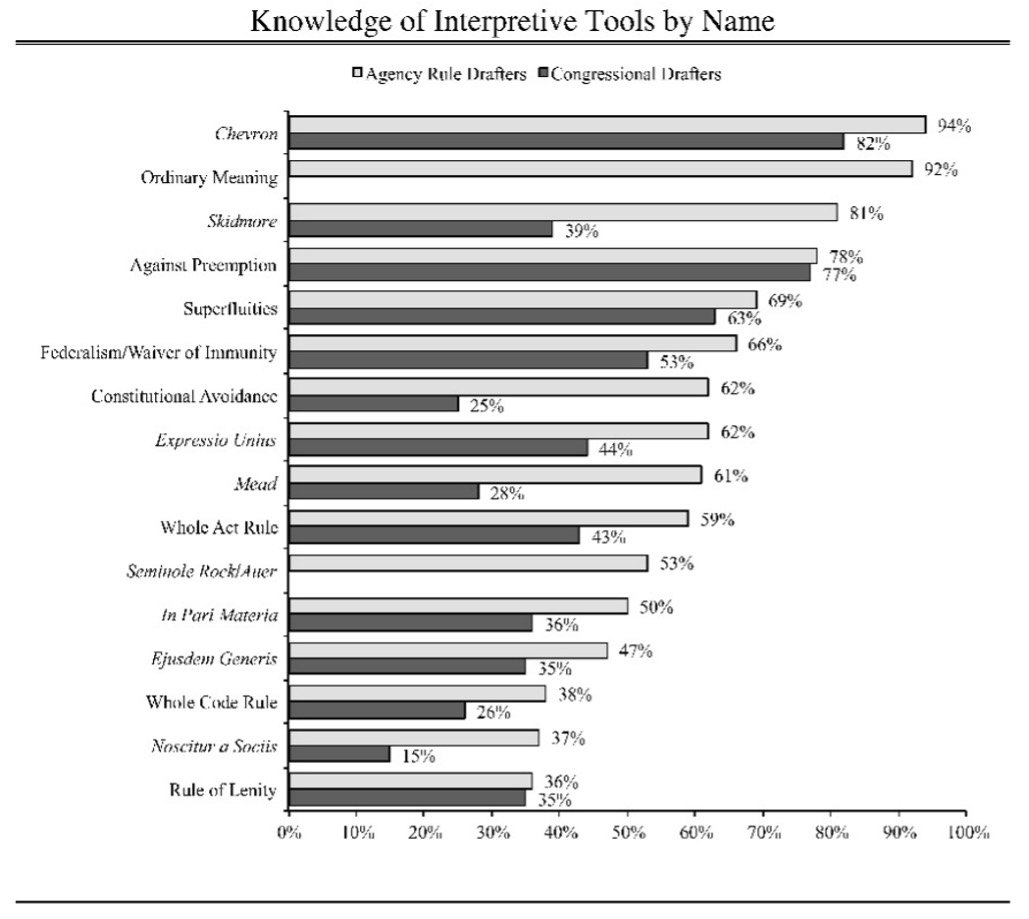

With respect to congressional drafters’ reliance on Chevron, Professors Abbe Gluck and Lisa Bressman have conducted the most extensive empirical study.56Abbe R. Gluck & Lisa Schultz Bressman, Statutory Interpretation from the Inside—An Empirical Study of Congressional Drafting, Delegation, and the Canons: Part I, 65 Stan. L. Rev. 901 (2013). In 2011–2012, they interviewed 137 congressional drafters, asking them 171 questions about the canons of statutory interpretation, legislative history, and administrative law doctrines.57See id. at 905–06. Notably, Chevron was the most known—by name (82%) and by concept (91%)—of any interpretive tool in the study.58Id. at 927–28 figs.1 & 2, 997. Nine in ten (91%) congressional drafters stated that one reason for allowing statutory ambiguity is to delegate decisionmaking to agencies, with “lack of time (92%),” “complexity of the issue (93%),” and “need for consensus (99%)” being other predominant reasons.59Id. at 997.

The central importance and settled nature of Chevron as an interpretive tool is also borne out within federal agencies. One of us conducted a parallel study of agency rule drafters, asking 128 agency rule drafters at seven executive departments and two independent agencies 195 questions about how they interpret statutes and draft regulations.60See Christopher J. Walker, Inside Agency Statutory Interpretation, 67 Stan. L. Rev. 999, 1004, 1013 (2015). Among all the interpretive tools in the survey, Chevron was most known by name (94%) and most used in statutory interpretation (90%) by the agency respondents.61Id. at 1019–20 figs.1 & 2. More than nine in ten agency rule drafters believed that statutory ambiguities related to implementation details (99%) or within the agency’s areas of expertise (92%) are ones Congress intended for the agency to fill, with far fewer respondents believing the same about major policy questions (56%), major economic questions (49%), major political questions (32%), or serious constitutional questions (24%).62Id. at 1053 fig.10; see also Christopher J. Walker, Chevron Inside the Regulatory State: An Empirical Assessment, 83 Fordham L. Rev. 703, 721–25 (2014) (exploring how the agency rule drafters surveyed perceived differences in agency regulatory activity based on whether the agency thinks it will receive Chevron deference). Figure 1 from that study, which depicts the high-level findings from both the Gluck-Bressman and Walker studies, is reproduced here.

Figure 1: Knowledge of Interpretive Tools by Name63Walker, supra note 60, at 1019 fig.1.

Moreover, the settled nature of Chevron is reflected in how the federal courts of appeals have applied the doctrine over the years, to which we return in Section II.A. And the same is no doubt true in how the regulated public has structured its operations and affairs in light of judicial decisions relying on Chevron. This settled understanding is of utmost importance when the Court weighs whether to reconsider a precedent like Chevron. As the Court explained, “Stare decisis has added force when the legislature, in the public sphere, and citizens, in the private realm, have acted in reliance on a previous decision.”64Hilton v. S.C. Pub. Rys. Comm’n, 502 U.S. 197, 202 (1991). That is because “overruling the decision would dislodge settled rights and expectations or require an extensive legislative response.”65Id. Chevron is one cornerstone of judicial doctrine on which numerous agency interpretations—on top of which property, contract, and entitlement interests sit—are grounded. If the Court abrogates Chevron, it then, to paraphrase the Court in Kisor v. Wilkie,66139 S. Ct. 2400 (2019). “cast[s] doubt on many settled [agency interpretations]” and “introduces . . . much instability into so many areas of law, all in one blow.”67Id. at 2422.

Finally, Chevron is no methodological or procedural precedent that would receive lesser stare decisis weight. In Loper Bright, the petitioners analogized Chevron to the now-overturned order-of-battle decisional rule in qualified immunity, which instructed courts to first decide whether the alleged conduct violates a constitutional right before determining whether that constitutional right was clearly established.68See Brief for Petitioners, supra note 4, at 21 (citing Pearson v. Callahan, 555 U.S. 223, 232–34 (2009)). But Congress never legislated against the backdrop of that order-of-battle rule. No outcome in any case hinged on whether a court followed the procedural rule. The precedent merely “involve[ed] internal Judicial Branch operations.”69Pearson, 555 U.S. at 233–34. Neither governments and their officials nor members of the public “order[ed] their affairs” around the procedural rule.70Id. at 233. For these reasons, Justice Alito, writing for the unanimous Court in Pearson v. Callahan,71555 U.S. 223 (2009). correctly concluded that, in that procedural context, “[a]ny change should come from this Court, not Congress.”72Id. at 234.

Instead, the better analogy here is the Court’s recognition of a qualified immunity defense in 42 U.S.C. § 1983. With both Chevron and qualified immunity, the Court interprets federal statutes to incorporate background legal principles.73See Aaron L. Nielson & Christopher J. Walker, A Qualified Defense of Qualified Immunity, 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1853, 1864–68 (providing examples of historical principles underlying 42 U.S.C. § 1983). Both affect outcomes when raised in litigation.74See id. at 1870–71 (discussing the rise in cases brought under 42 U.S.C. § 1983); see also id. at 1875–76 (listing statistics on cases involving qualified immunity issues). Indeed, the fact that Chevron has a substantive effect is exactly why the petitioners and numerous amici curiae in Loper Bright and Relentless seek its abrogation.75See, e.g., Brief for Petitioners, supra note 4, at 33. Congress has legislated against the backdrop of both precedents in other statutes.76See Nielson & Walker, supra note 73, at 1858. And it has considered, though not passed, legislation to abolish both.77See id. at 1856–63 (defending qualified immunity on stare decisis grounds). Finally, similar to how federal agencies and the regulated public have ordered their affairs around Chevron, state and local governments and their officials have structured their affairs around qualified immunity, including in terms of officer indemnification laws and contractual arrangements.78See generally Aaron L. Nielson & Christopher J. Walker, Qualified Immunity and Federalism, 109 Geo. L.J. 229 (2020) (conducting a state-by-state survey of indemnification laws and examining states’ reliance on qualified immunity).

C. Chevron, APA Originalism, and Uncertainty

To be sure, statutory stare decisis is not insurmountable. A critical inquiry concerns how erroneous the statutory precedent is as a matter of original meaning. As to Chevron deference and the original understanding of section 706 of the APA, the answer is far from clear.

In recent years, Professor Aditya Bamzai has advanced an originalist argument against Chevron.79See generally Aditya Bamzai, The Origins of Judicial Deference to Executive Interpretation, 126 Yale L.J. 908, 912–19 (2017) (“Chevron cleared up this confusion [regarding judicial review of agency interpretation] by departing from, rather than seeking out, the meaning of the APA’s text and the traditional interpretive methodology.”). In concluding that Chevron is not originalist, Professor Bamzai looks to the theory and practice of interpretation before the APA.80Id. at 916–18. He argues that judicial deference to executive interpretation began only after the APA, and to the extent courts deferred to agencies beforehand, the APA was enacted “to stop this deviation.”81Id. Under this approach, the “most natural reading” is that section 706 “established deferential standards of review for issues other than ‘relevant questions of law,’ thereby indicating that Congress knew how to write a deferential standard into statute when it wanted to do so.”82Id. at 985, 987 (internal footnote omitted) (quoting 5 U.S.C. § 706); see also John F. Duffy, Administrative Common Law in Judicial Review, 77 Tex. L. Rev. 113, 193–99 (1998) (arguing that Chevron cannot be squared with the text of section 706 of the APA).

Professors Ron Levin and Cass Sunstein have both written thoughtful responses. Professor Levin concludes that “the text of § 706, related APA provisions, legislative history, case law background, and contemporaneous understanding all fail to support the no-deference interpretation of § 706.”83Ronald M. Levin, The APA and the Assault on Deference, 106 Minn. L. Rev. 125, 130 (2021). He argues that Professor Bamzai understates the extent to which pre-APA caselaw relied on deference principles.84Id. at 167–70. In Professor Levin’s view, the drafters of the APA wrote broad language into the APA because they were not particularly concerned about the issue of judicial deference on legal questions.85See id. at 170–74. Indeed, he contends, almost all contemporaneous courts and commentators understood the APA as having made no change in the law on this subject.86See id. at 175–83. Professor Sunstein similarly concludes that, “in the 1940s, the contextual evidence on behalf of Bamzai’s claim is not strong. Actually, it is difficult to find, and that difficulty can be seen as a dog who did not bark in the night—a probative silence.”87Cass R. Sunstein, Chevron as Law, 107 Geo. L.J. 1613, 1650 (2019). Despite the Court noting shortly after the APA’s enactment that the APA changed how courts were thought to review factual findings and how agencies separated functions internally, the Court never indicated that the APA altered deference to agency legal interpretations.88See id. at 1653–54. Instead, the Court continued to apply deference to agency legal interpretations in terms strikingly similar to Chevron’s formulation without any meaningful pushback—both shortly after the APA’s enactment and in the decades leading up to Chevron itself.89See id. at 1654–56.

The APA originalism debate over Chevron deference continues.90Compare Aditya Bamzai, Judicial Deference and Doctrinal Clarity, 82 Ohio St. L.J. 585, 608–09 (2021), with Cass R. Sunstein, Zombie Chevron: A Celebration, 82 Ohio St. L.J. 565, 565–68 (2021). See also Kristin E. Hickman & R. David Hahn, Categorizing Chevron, 81 Ohio St. L.J. 611, 650–70 (2020) (considering Chevron as a standard of review); Michael B. Rappaport, Chevron and Originalism: Why Chevron Deference Cannot Be Grounded in the Original Meaning of the Administrative Procedure Act, 57 Wake Forest L. Rev. 1281, 1307–11, 1314–23 (2022) (responding to Levin and Sunstein). A careful review of the scholarship published to date does not provide a clear answer, and certainly does not support the conclusion that, as the petitioners in Loper Bright put it, “Chevron is egregiously wrong.”91Brief for Petitioners, supra note 4, at 23; see also Caleb Nelson, Stare Decisis and Demonstrably Erroneous Precedents, 87 Va. L. Rev. 1, 1–2 (2001). The dispute surrounding cryptic phrases, unclear historical accounts, and judicial practice immediately after the APA’s enactment in 1946 provides no basis for ignoring the strong pull of statutory stare decisis for Chevron.

D. Chevron’s Clear Constitutionality

If Chevron were clearly unconstitutional, stare decisis would pose little barrier to overruling the precedent. But the constitutional arguments against Chevron to date fall far short. Those arguments can be roughly grouped in two camps: Article I concerns and Article III concerns.92See Christopher J. Walker, Attacking Auer and Chevron Deference: A Literature Review, 16 Geo. J.L. & Pub. Pol’y 103, 110 (2018).

The first argument is that Article I of the U.S. Constitution vests Congress with “[a]ll legislative Powers,” yet Chevron encourages members of Congress to delegate broad lawmaking power to federal agencies.93Id. at 112; U.S. Const. art. 1, § 1. In doing so, Congress frustrates the values of the nondelegation doctrine.94See Walker, supra note 92, at 112–13. The problem with this argument is that Chevron itself does not cause the constitutional violation. Chevron explicitly instructs reviewing courts to say what the law is, “employing traditional tools of statutory construction.”95Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 843 n.9 (1984). Instead, the argument rests with Congress’s decision to delegate too broadly; the nondelegation doctrine is the constitutional tool to address that.96See infra Part III (returning to these Article I concerns in light of the major questions doctrine). Even under a strict version of the nondelegation doctrine, Congress may allow those charged under “general provisions to fill up the details.”97Wayman v. Southard, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) 1, 43 (1825). Chevron simply permits Congress to delegate to agencies to decide those details as long as Congress has provided enough direction with its general provision.

The second argument is that deference to agencies’ reasonable statutory interpretations violates Article III because courts are no longer able to “say what the law is,” à la Marbury v. Madison.985 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 177 (1803); see Baldwin v. United States, 140 S. Ct. 690, 691 (2020) (Thomas, J., dissenting from the denial of certiorari); Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 1142, 1151–52, 1156 (10th Cir. 2016) (Gorsuch, J., concurring). Yet, the Court has established a much more nuanced Article III jurisprudence that does not require courts to answer legal questions de novo or provide a remedy in all instances,99See generally Kent Barnett, How Chevron Deference Fits into Article III, 89 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1143, 1144–48 (2021) (describing Chevron as a “relatively minor Article III issue”). even putting aside the numerous forms of deferential review that the courts have applied in various formulations to executive legal interpretations.100Brief for the Respondents, supra note 13, at 23–25. Given that mandamus review at the Founding operated in an extremely similar manner to Chevron deference, those who argue that Chevron deference violates Article III must provide some theory for why such deference with the legal remedy of mandamus was permissible but somehow is impermissible with other forms of relief, even when those forms of relief have the same practical effect as mandamus.

Although the Court on occasion has expressed hesitation if certain agency actions are unreviewable, it has never suggested any categorical concern over no-review clauses, which have existed since at least the 1930s.101See 5 U.S.C. § 701(a)(1) (stating that the APA’s judicial review provisions do not apply when “statutes preclude judicial review”); Laura E. Dolbow, Barring Judicial Review, 77 Vand. L. Rev. (forthcoming 2024) (manuscript at 14–26, app. B) (identifying nearly 200 judicial review bars in the U.S. Code), https://perma.cc/T9RZ-BM6P; cf. United States v. Erika, 456 U.S. 201, 205–06 (1982) (holding that Congress deprived federal courts of jurisdiction to review certain Medicare benefits adjudications); Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361, 367 (1974) (noting that Congress’s intent to preclude review of certain veterans’ benefits decisions did not extend to constitutional challenges). Because Congress can preclude judicial review altogether of some or all claims under Article III, it is difficult to see how reasonableness review offends Article III, especially when the Court and its members have relied on greater-includes-the-lesser-power reasoning in its Article III jurisprudence102For instance, the plurality relied on this reasoning when explaining why Congress has more room under Article III to decide how private rights that it creates, as opposed to those created by the States, may be litigated. See N. Pipeline Constr. Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50, 80–81 (1982) (plurality opinion). The Court applied similar reasoning when explaining why Congress could under Article III limit courts’ equitable remedies. See Lockerty v. Phillips, 319 U.S. 182, 187–88 (1943). and when Chevron concerns the interpretation of statutes Congress itself enacted. Indeed, Congress has narrowed judicial review in other contexts, such as the limited federal judicial review of state-court judgments under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (“AEDPA”).103See 28 U.S.C. § 2254(d)(1); e.g., White v. Woodall, 572 U.S. 415, 419–20 (2014). In rejecting an Article III challenge to section 2254(d) of AEDPA, Judge Frank Easterbrook for the en banc Seventh Circuit noted that as goes section 2254(d) so goes Chevron:

If . . . federal courts must give judgment without regard to the legal views of other public actors, and without regard to the resolution of contested issues in state litigation, then [the] argument reaches far beyond § 2254(d). It would mean that deference in administrative law under Chevron is unconstitutional . . . .104Lindh v. Murphy, 96 F.3d 856, 871 (7th Cir. 1996) (en banc), rev’d on other grounds, 521 U.S. 320 (1997); see also Bowling v. Parker, 882 F. Supp. 2d 891, 897–900 (E.D. Ky. 2012) (rejecting Article III challenge to § 2254(d)).

Additionally, courts cannot refuse to confirm an arbitration award based on disagreements with an arbitrator’s legal interpretations.105See 9 U.S.C. §§ 10–11; see also Thomas v. Union Carbide Agric. Prods. Co., 473 U.S. 568, 592–93 (1985) (rejecting Article III challenge to the extremely limited judicial review of statutorily required arbitration scheme). At best, courts may be able to decline to confirm an award when the arbitrator demonstrated a “manifest disregard for the law,” but even this extremely limited ground for refusing enforcement of the award is questionable under the Court’s precedent. See Paul Green Sch. of Rock Music Franchising, LLC. v. Smith, 389 F. App’x 172, 176 & n.6 (3d Cir. 2010).

These are just two of many examples where Congress has imposed limits on judicial review. Perhaps Chevron offends Article III in certain contexts, such as when private rights are at issue or agency interpretations lead to criminal liability.106See Barnett, supra note 99, at 1193–97. But for one to suggest that Chevron’s reasonableness review offends Article III in all or some cases, one must do much more than simply invoke Marbury v. Madison, announce victory, and move on.107For similar reasons, Professor Philip Hamburger’s arguments about due process and pro-government institutional bias fail as a constitutional matter. See Philip Hamburger, Chevron Bias, 84 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1187, 1189 (2016).

II. Chevron’s Overlooked Rule-of-Law Values

Overturning Chevron is not only inconsistent with statutory stare decisis, but it would also frustrate the rule-of-law values Chevron advances. The conventional values in the caselaw and literature on Chevron include respect for congressional delegation, comparative agency expertise, deliberative process in policymaking, and political accountability in law implementation.108See, e.g., Evan J. Criddle, Chevron’s Consensus, 88 B.U. L. Rev. 1271, 1284–91 (2008). Based on our empirical study of Chevron in the federal courts of appeals, we focus on two less studied values of Chevron: greater national uniformity in federal law, and less politics in judicial decisionmaking. These normative values that Chevron advances strengthen the pull of stare decisis.

A. National Uniformity in Federal Law

Chevron deference promotes national uniformity in federal law by limiting courts’ responsibility for determining the best reading of a statute. Instead, courts need to assess only the reasonableness of an agency’s interpretation, rendering it more likely that lower federal courts across the country will agree in accepting or rejecting the agency’s interpretation.109See Peter L. Strauss, One Hundred Fifty Cases per Year: Some Implications of the Supreme Court’s Limited Resources for Judicial Review of Agency Action, 87 Colum. L. Rev. 1093, 1121–22 (1987). Moreover, by providing agencies space for interpreting statutory ambiguities, Chevron provides a disincentive for judicial challenges and thereby allows the agency to provide a national standard even absent judicial review.110See City of Arlington v. FCC, 569 U.S. 290, 307 (2013). The Court has called this Chevron’s “stabilizing purpose.”111Id.

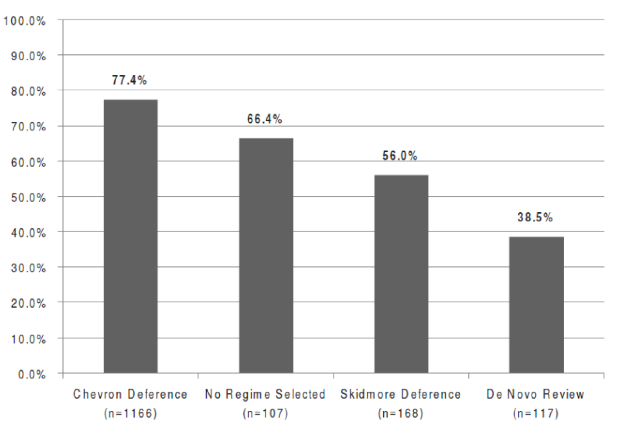

Our earlier empirical research on Chevron supports this stabilizing purpose. We compiled the largest dataset to date on Chevron and Skidmore deference in the courts of appeals. Our dataset is comprised of all published three-judge-panel, courts-of-appeals decisions that refer to Chevron or Skidmore over eleven years (from 2003 to 2013) and provides judicial review of agency statutory interpretation, whatever the standard of review.112Our research design leaves open the unavoidable possibility that additional relevant published courts-of-appeals opinions exist that cite neither Chevron nor Skidmore. See Kent Barnett & Christopher J. Walker, Chevron in the Circuit Courts, 116 Mich. L. Rev. 1, 21–27 (2017) (detailing the methodology and its limitations); see also Kent Barnett, Christina L. Boyd & Christopher J. Walker, The Politics of Selecting Chevron Deference, 15 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 597, 597 (2018). The final version of this dataset includes 1,613 agency statutory interpretations in 1,382 decisions (meaning that a decision may concern more than one agency statutory interpretation).113See Barnett & Walker, supra note 112, at 27–30. We coded the decisions for some forty variables.114See id. at 5–6. Figure 1 from our study, reproduced below, breaks down how often agency interpretations prevail under different standards of review:

Figure 2: Agency-Win Rates by Deference Standard115. Id. at 30 fig.1.

The bottom-line takeaway, descriptively speaking, is that there is a difference of nearly twenty-five percentage points in prevalence rates when judges decide to apply the Chevron deference framework, as compared to when they do not, in the decisions reviewed.

Of course, one should be careful not to read too much into these descriptive findings, as there are also great differences in prevalence rates by agency, circuit court, and subject matter. Similarly, methodological limitations inherent in this study, as is typical with any coding project, should counsel caution. A more sophisticated statistical analysis of these findings is discussed in Section II.B. That said, even these raw-number findings make it hard to argue that Chevron does not matter in the circuit courts in terms of encouraging national uniformity in federal law. Under Chevron, an agency’s nationwide policy implementation of a statute it administers is more likely to govern, as opposed to a patchwork scheme of potentially conflicting judicial interpretations as different courts provide their own best readings of the statutes.

B. Limits on Politics in Judicial Decisionmaking

Another critical rule-of-law value of Chevron is that it limits judges from deciding cases based on their personal policy preferences. Chevron itself noted that deference to agencies’ interpretations of ambiguous statutory provisions leaves the resolution of competing policy determinations to the political branches.116See Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 865–66 (1984).

We found in our empirical research that Chevron is largely meeting this goal of removing judges from deciding policy—that is, political—matters. Along with our co-author and political scientist Dr. Christina Boyd, we leveraged our dataset to explore the political dynamics of judicial decisionmaking.117See generally Kent Barnett, Christina L. Boyd & Christopher J. Walker, Administrative Law’s Political Dynamics, 71 Vand. L. Rev. 1463 (2018) (finding that the “Chevron Court’s objective to reduce partisan judicial decision-making has been quite effective”). Our findings, by comparing how judges review interpretations under Chevron or other standards of review, demonstrate that Chevron muted ideological decisionmaking on the federal courts of appeals, even if it did not fully constrain it.118Id. at 1502. The most liberal panels agreed with conservative agency statutory interpretations only 24% of the time when they did not use Chevron deference but 51% when they did.119Id. at 1500. Likewise, the most conservative panels agreed with liberal agency interpretations only 18% of the time without Chevron deference but 66% with it.120Id. at 1499. Nonetheless, political judicial decisionmaking still likely exists, even with Chevron deference’s ameliorating effects. We found that conservative panels were up to 23% more likely than liberal panels to agree with conservative agency interpretations under Chevron deference, as compared to up to 36% more likely than liberal panels under a lesser form of deference.121Id. at 1468. Likewise, we found a 25% difference for review of liberal agency interpretations under Chevron (with liberal panels being more likely than conservative ones to agree) and a sizable 63% difference without Chevron deference.122Id. at 1502.

Ultimately, our findings provide compelling evidence that Chevron has, to a substantial degree, succeeded in removing judges from policy decisions that Congress has delegated to agencies. By doing so, it has promoted stability in judicial decisionmaking across ideologically varied courts of appeals and panels, increasing national uniformity and predictability in federal law. Without Chevron, courts would be left with de novo review or at most a multi-factor-based Skidmore review standard. There can be no serious argument that either of these alternative standards of review would be more workable than Chevron—i.e., would better promote rule-of-law values of predictability and uniformity in federal law. Justice Antonin Scalia was correct to observe that “[t]hirteen Courts of Appeals applying a totality-of-the-circumstances test would render the binding effect of agency rules unpredictable and destroy the whole stabilizing purpose of Chevron.”123City of Arlington v. FCC, 569 U.S. 290, 307 (2013). In its amicus curiae brief supporting the petitioners in Loper Bright, the Competitive Enterprise Institute argues that Chevron is contrary to the stability of stare decisis because different administrations can implement different interpretations. Brief of Competitive Enterprise Institute as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioners at 7–13, Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, No. 22-451 (U.S. July 24, 2023). Even when agencies change positions, agencies’ failure to account for reliance interests would render their action arbitrary and capricious under the APA. See Dep’t of Homeland Sec. v. Regents of the Univ. of Cal., 140 S. Ct. 1891, 1913 (2020). Given that Chevron recognizes that congressional delegation allows agencies to act differently, yet reasonably, in response to statutory ambiguities or silences, this criticism of the limited space that agencies have to interpret ambiguous statutory provisions is best made to Congress, not the Court. Moreover, as discussed later in Part III, the Court’s recent Chevron precedents have addressed this issue. In all events, as detailed previously in Part II, we are not convinced that stability in regulatory law would be greater in a world without Chevron.

III. The Future of Chevron

Chevron as articulated by the Court is constitutional, and when properly applied, it advances rule-of-law values in administrative law. The concerns that the Loper Bright and Relentless petitioners and others raise are not really about Chevron as properly applied. Instead, they concern when Chevron is misapplied—when it becomes merely a “reflexive deference,” as Justice Anthony Kennedy aptly called it.124Pereira v. Sessions, 138 S. Ct. 2105, 2120 (2018) (Kennedy, J., concurring). When courts fail to patrol the bounds of statutory ambiguity, they allow federal agencies to exceed the policymaking authority Congress granted to the agencies by statute.

In recent years, the Court has taken a number of measures to address concerns about Chevron’s application. First, the Court has instructed reviewing courts to take Chevron footnote nine seriously.125See, e.g., Wis. Cent. Ltd. v. United States, 585 U.S. 274, 283 (2018). At Chevron step one, courts must determine whether the statutory provision at issue is ambiguous, “employing traditional tools of statutory construction.”126Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 843 n.9 (1984). Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the Court, has reiterated that if the statute is “clear enough,” then the agency gets no deference at step one.127Wis. Cent., 585 U.S. at 283.

Second, the Court has instructed reviewing courts to take Chevron footnote eleven seriously. At Chevron step two, courts must ensure that an agency’s interpretation is “permissible” or “reasonable.”128Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837, 843–44 & n.11 (1984). Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the Court, has stressed that to be reasonable, an agency’s interpretation “must come within the zone of ambiguity the court has identified after employing all its interpretive tools.”129Kisor v. Wilkie, 139 S. Ct. 2400, 2416 (2019) (concerning agency interpretations of their own regulations). She continued: “And let there be no mistake: That is a requirement an agency can fail.”130Id. Elsewhere, Justice Kagan, again writing for the Court, has compared Chevron step two to APA arbitrary-and-capricious review.131See Judulang v. Holder, 565 U.S. 42, 52 n.7 (2011) (“Were we to [use Chevron step two], our analysis would be the same, because under Chevron step two, we ask whether an agency interpretation is arbitrary or capricious in substance.” (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Mayo Found. for Med. Educ. & Rsch. v. United States, 562 U.S. 44, 53 (2011))). We have called on the Court to provide more guidance on the nature of step two, noting that the Court’s apparent directions on step two do not always seem consistent with how it applies that step in practice.132See Kent Barnett & Christopher J. Walker, Chevron Step Two’s Domain, 93 Notre Dame L. Rev. 1441, 1468–71 (2018).

Finally, over the last two years, the Court has further developed the major questions doctrine as a threshold check on administrative action and congressional delegation. In West Virginia v. EPA,133142 S. Ct. 2587 (2022). the Court explained that when agencies claim authority to regulate certain major policy questions, “something more than a merely plausible textual basis for the agency action is necessary. The agency instead must point to clear congressional authorization for the power it claims.”134Id. at 2609 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting Util. Air Regul. Grp. v. EPA, 573 U.S. 302, 324 (2014)); accord Biden v. Nebraska, 143 S. Ct. 2355, 2375 (2023); Nat’l Fed’n of Indep. Bus. v. OSHA, 142 S. Ct. 661, 665–66 (2022); Ala. Ass’n of Realtors v. Dep’t of Health & Hum. Servs., 141 S. Ct. 2485, 2489–90 (2021). We take no position here on the wisdom of this invigorated major questions doctrine. But any discussion about the future of Chevron must consider the major questions doctrine’s impact. It eviscerates the Article I concerns discussed in Section I.D about Congress abdicating its duty—either as a constitutional matter on nondelegation doctrine grounds or as a normative separation-of-powers concern—to make the major value judgments in federal lawmaking.135In their amici curiae brief supporting the petitioners in Loper Bright, Senator Ted Cruz and thirty-five other members of Congress argue that Chevron introduces indeterminacy because judges have a hard time agreeing on what it means for a statute to be ambiguous. See Brief of U.S. Senator Ted Cruz, Congressman Mike Johnson, and 34 Other Members of Congress as Amici Curiae Supporting Petitioners at 18–19, Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, No. 22-451 (U.S. July 24, 2023). As noted in previously in Section II.B, it is difficult to imagine more predictability and determinacy in judicial review of agency statutory interpretations in a world of de novo review or a less deferential standard like Skidmore. This intermediacy argument, taken to its logical conclusion, would apply to all judicial precedents that require judgment, including routine judicial decisions as to whether a contractual provision is ambiguous and subject to a fact finder’s determination over the provision’s meaning. And it would certainly apply to the major question doctrine’s inquiries into whether a policy question is “major” and, if so, whether Congress has clearly authorized the agency to regulate it.

If reviewing courts take Chevron footnotes nine and eleven seriously and apply the major questions doctrine, Chevron would apply only when Congress has delegated via ambiguity comparatively minor policymaking authority and the agency has reasonably exercised that authority. An agency would retain policymaking discretion—in Chief Justice Marshall’s words—to “fill up the details” of a statutory scheme,136Wayman v. Southard, 23 U.S. (10 Wheat.) 1, 43 (1825). where the agency has comparative expertise and accountability over courts and where national uniformity in law is paramount for the regulated and the public more generally.

Conclusion

Ultimately, when considering whether to abandon Chevron, the Supreme Court finds itself in the following place:

With these points in mind, the force of stare decisis strongly supports the Supreme Court’s reaffirmation of Chevron in Loper Bright and Relentless.