Introduction: Following the Wake of Allen

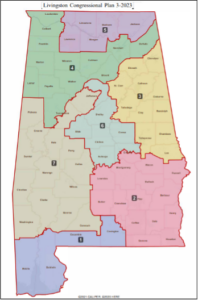

Alabama found itself in a tough spot following the Supreme Court’s 2023 decision, Allen v. Milligan,1 143 S. Ct. 1487 (2023). affirming a three-judge panel’s decision requiring the state to redraw its congressional map to add a second majority-minority district.2See id. at 1502 (affirming Singleton v. Merrill, 582 F. Supp. 3d 924 (N.D. Ala. 2022) (per curiam)). Wes Allen succeeded John Merrill as Alabama Secretary of State in 2023, replacing Merrill as defendant in the redistricting case. This Comment defines a majority-minority district as a legislative district where a majority of voters are of minority races. Following the loss, Alabama could either (1) comply with the panel’s order and draw a compliant congressional map with two majority-minority districts, or (2) refuse to draw a compliant map and risk a new legal challenge and a repeat of the panel’s rejection. Alabama chose the latter by redrawing its congressional map without a second majority-minority district.3Singleton v. Allen, 690 F. Supp. 3d 1226, 1243–44 (N.D. Ala. 2023). See Ala. Code § 17-14-70(b) (2023) (providing authority for the Alabama legislature to propose congressional maps); infra Figure 1.

Figure 1: Livingston Congressional Plan Three4Singleton, 690 F. Supp. 3d at 1244 (reproducing a map image found on the Alabama Legislature web page).

The District Court for the Northern District of Alabama rebuked and condemned Alabama’s redrawn map: “[W]e are deeply troubled that the State enacted a map that the State readily admits does not provide the remedy we said federal law requires.”5Id. at 1239. The lower court continued:

We are disturbed by the evidence that the State delayed remedial proceedings but ultimately did not even nurture the ambition to provide the required remedy. And we are struck by the extraordinary circumstance we face. We are not aware of any other case in which a state legislature — faced with a federal court order declaring that its electoral plan unlawfully dilutes minority votes and requiring a plan that provides an additional opportunity district — responded with a plan that the state concedes does not provide that district.6Id.

Nonetheless, Alabama appealed and requested an emergency stay of the decision, but the Supreme Court denied the emergency stay and allowed the panel to determine the new districts.7See Emergency Application for Stay Pending Petition for Writ of Certiorari Before Judgment at 40, Allen v. Caster, 144 S. Ct. 476 (2023) (No. 23A241) (requesting an emergency stay of the lower court panel decision); Allen v. Caster, 144 S. Ct. 476, 476 (2023) (mem.) (denying the emergency stay request).

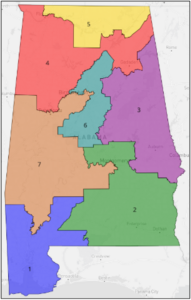

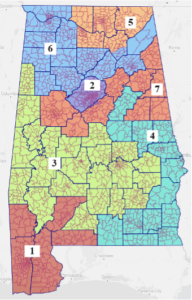

The panel adopted the special master’s map to define Alabama’s congressional districts for the next decade.8Singleton v. Allen, No. 2:21-cv-1291, 2023 WL 6567895, at *19 (N.D. Ala. Oct. 5, 2023). The special master’s map (Figure 3)—sharing many similarities with the state legislature’s original proposal and the original congressional map—still uses race as a predominant factor and pulls all but one major city out of its corresponding metropolitan region to create two majority-minority districts, each safely Democratic.9See id. at *17 (noting the Alabama Legislators’ and Secretary of State’s argument that the Special Master’s remedial maps “allowed race to predominate over traditional districting principles”). Notwithstanding the panel’s opinion, approval of Remedial Plan 3 invariably required assessing the racial composition of voting districts, regardless of such assessment occurring after the map’s drawing. See infra Figures 2 & 3. These two maps allow for a comparison of Alabama’s current congressional district map, which packs District Seven to retain one majority-minority and safe Democratic district, with Remedial Plan 3, which packs Districts Two and Seven to create two majority-minority and safe Democratic districts.

Figure 2: Alabama’s 2021–2022 Congressional Districts102022 Alabama Congressional Districts: Map, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/V9A3-SX5M (recreating a map image found in Singleton v. Merrill, 582 F. Supp. 3d 924, 951 (N.D. Ala. 2022)). To improve clarity, this map figure was recreated by Dave’s Redistricting, “a free web app to create, view, analyze and share redistricting maps” using publicly available sources. About DRA, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/DTC9-5MME. All permalinks to Dave’s Redistricting require the reader to visit the live page to view the map.

| 2022 Alabama Congressional Districts11 2022 Alabama Congressional Districts: Statistics, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/SF84-M5JG. Partisan Advantage is computed as the absolute value of the difference between a district’s “Republican % of the vote” and “Democratic % of the vote” found in the linked data. Note that District Seven is the only majority-minority and safe Democratic district. This Comment treats a district as “safe” for a political party if the partisan advantage exceeds eight points. | ||

| District | Minority Population Percentage | Partisan Advantage (|R – D|) |

| One | 34.00% | R + 21.77% |

| Two | 37.97% | R + 25.74% |

| Three | 32.26% | R + 28.71% |

| Four | 17.59% | R + 54.49% |

| Five | 29.11% | R + 22.59% |

| Six | 28.84% | R + 25.84% |

| Seven | 61.40% | D + 36.71% |

Figure 3: Special Master’s “Remedial Plan 3”12Singleton v. Allen, No. 2:21-cv-1291, 2023 WL 6567895, at *19 (N.D. Ala. Oct. 5, 2023).

| 2023 Special Master Remedial Plan Three13 Hooper 2023 Special Master Remedial Plan Three: Statistics, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/PD6X-9K6G. This table demonstrates that Districts Two and Seven are now majority-minority districts and favor Democrats by safe margins. For the Partisan Advantage calculation, see supra note 11. | ||

| District | Minority Population Percentage | Partisan Advantage (|R – D|) |

| One | 24.83% | R + 55.53% |

| Two | 56.09% | D + 9.39% |

| Three | 28.26% | R + 45.02% |

| Four | 16.84% | R + 66.12% |

| Five | 29.60% | R + 32.10% |

| Six | 25.07% | R + 44.74 % |

| Seven | 60.20% | D + 29.14% |

In other words, the Supreme Court’s Allen decision subjected Alabama’s congressional districts to the great flaw of the Court’s racial gerrymandering and vote dilution jurisprudence: Advancing race-based districts at the cost of contiguous and compact districts capable of representing popular interests, which arguably violates the Fourteenth Amendment.14See Alexander v. S.C. State Conf. of the NAACP, 144 S. Ct. 1221, 1255 (2024) (Thomas, J., concurring in part) (“The difference between illegitimate packing and the legitimate pursuit of compactness is too often in the eye of the beholder.”); Allen v. Milligan, 143 S. Ct. 1487, 1538–39 (2023) (Thomas, J., dissenting) (“[I]f complying with a federal statute would require a State to engage in unconstitutional racial discrimination, the proper conclusion is not that the statute excuses the State’s discrimination, but that the statute is invalid.”).

Yet, Alabama is not the first state to have gerrymandered districts due to majority-minority districts.15See Appendix 1 (listing gerrymandered majority-minority districts from across the country). For example, majority-minority districts in Illinois, Texas, and Louisiana represent some form of “cracking” or “packing” to weaken the opposing party’s congressional representation.16See id. For the definition of “cracking,” see infra note 138. For the definition of “packing,” see infra note 105.

This Comment acknowledges the shortfalls of Alabama’s current congressional map but argues that the Thornburg v. Gingles17478 U.S. 30 (1986). preconditions, affirmed by Allen, conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment’s restriction on using race as a dominant redistricting principle.18See Alexander, 144 S. Ct. at 1262 (Thomas, J., concurring in part) (criticizing the Court’s vote-dilution jurisprudence as “invariably fall[ing] back on racial stereotypes”); Allen, 143 S. Ct. at 1538–39 (Thomas, J., dissenting). Thus, this Comment proposes an objective tax approach that, instead, balances voter enfranchisement with representative districts while harmonizing the conflict between the Court’s application of the Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection Clause and the 1965 Voting Rights Act (“VRA”) Section Two analyses. Using taxes as the predominant redistricting approach ensures the constituents of a district are united under a few dominating interests, which provides representatives with strong incentives to advocate for those interests.

Under the tax approach, a court must analyze the degree to which (1) the constituents of a district benefit from the same or similar tax-funded institutions, and (2) the district contains similar tax revenue sources. Under the first factor, a court would compare tax-funded institutions within a legislative district, such as school districts, municipal services, hospitals, airports, large infrastructure projects, and recreational services. A district fails the first factor if the tax-funded institutions serve geographically separate populations or differ significantly from each other without a compelling reason, such as a district covering a large rural region. For the second tax factor, a court would consider keeping together regions with similar industries, such as agricultural, manufacturing, or white-collar firms. If a district combines two regions with contrasting industries when reasonable alternatives exist, then the district fails the second factor. A court may exercise its discretion, based on the facts of the contested map, when employing either factor or both to varying extents. The nature of both factors, which ultimately require municipalities and counties to remain intact, will successfully combat any bad faith attempts to weaken the electoral strengths of racial minorities or the minority political party. Likewise, a court must grant deference to the redistricting body if it provides a compelling interest that justifies the inclusion or exclusion of certain areas with similar tax characteristics.

In Part I, this Comment details the jurisprudence behind majority-minority districts leading up to Allen, beginning with the Constitution and the VRA. In Part II, this Comment describes the reasoning of majority and dissenting opinions in Allen and how it enables various states to continue gerrymandering. Part III then presents a map of Alabama that complies with the tax approach and walks through the analysis a court may use to evaluate such a map.

I. Background: The Constitutional and Jurisprudential Origins of Allen

This Part provides an overview of the Supreme Court’s relevant jurisprudence on racial gerrymandering claims under Section Two of the VRA and the Fourteenth Amendment. It first covers the relevant text of the Constitution’s Election Clause and the 1965 Voting Rights Act and analyzes the 1982 amendments following the Supreme Court’s City of Mobile v. Bolden19446 U.S. 55 (1980) (plurality opinion). decision. It then analyzes Gingles, including significant cases clarifying Gingles, and then analyzes Allen.

A. The Constitution, VRA Section Two, Bolden, and the 1982 Amendments

Like in many of its Article I provisions, the Constitution gives Congress broad powers in Article I, Section Four, Clause I—the Elections Clause. While state legislatures may regulate how they elect representatives and senators, Congress may alter such regulations.20U.S. Const. art. I, § 4, cl. 1. Add to this authority the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause and the Fifteenth Amendment’s prohibition on denying a citizen’s right to vote “on account of race” and Congress has its constitutional basis for combatting racial gerrymandering.21Id. amend. XIV, § 1 (“No State shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”); id. amend. XV, § 1 (“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”).

Congress’s first attempt at directly combatting racial gerrymandering, through the text of Section Two of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, did not create majority-minority districts. Rather, Section Two broadly prohibited any “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting [used] to deny or abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.”22Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, § 2, 79 Stat. 437, 437 (codified as amended at 52 U.S.C. § 10301(a)). In essence, Section Two clarified that the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments ensured every citizen could vote by preventing states from using voting barriers that disproportionately impacted minorities.23See id.; U.S. Const. amends. XIV, XV.

The VRA enjoyed peace in its relatively unmodified 1965 form until the Supreme Court issued its Bolden decision in 1980, which placed Alabama into the spotlight of Section Two-based litigation. This time, however, Alabama won.24See Bolden, 446 U.S. at 65, 70, 74, 80.

Since 1911, Mobile, Alabama, a medium-sized city on the Gulf of Mexico, governed itself with a three-member commission elected at-large, much like most other municipalities at that time.25Id. at 58, 60 n.7. In the late 1970s, however, a group of black citizens from Mobile sued the city, alleging the at-large system existed to discriminate against minority voters.26Brief for Appellees at 2, City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) (No. 77-1844), 1979 WL 213678, at *2.

Writing for a plurality, Justice Stewart held that because Mobile’s at-large voting system did not hinder black citizens from voting, it did not violate (1) Section Two, (2) Supreme Court precedent, (3) the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, or (4) the Fifteenth Amendment.27Bolden, 446 U.S. at 65. Ultimately, the black voters failed to present “proof that the at-large electoral scheme represents purposeful discrimination against” them.28Id. at 74. In reversing the lower courts, Justice Stewart ultimately concluded that “[t]he Fifteenth Amendment does not entail the right to have [black] candidates elected . . . .”29Id. at 65.

Congress disagreed with the Bolden decision and amended Section Two.30For a detailed version of the legislative history behind the amended Section Two, see generally Thomas M. Boyd & Stephen J. Markman, The 1982 Amendments to the Voting Rights Act: A Legislative History, 40 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 1347 (1983). In its 1982 amendments to Section Two, Congress added subsection (b), detailing how to establish a violation under the original Section Two.31Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-205, § 3, 96 Stat. 131, 134 (codified at 52 U.S.C. § 10301(b)). Under subsection (b), Congress imposed a “totality of circumstances” standard to ensure voters could challenge facially neutral statutes despite no known discriminatory motivation from the government, as required by Bolden.32Id.; Bolden, 446 U.S. at 62. Under the totality standard, a plaintiff must show:

[T]he political processes leading to nomination or election in the State or political subdivision are not equally open to participation by members of a class of citizens protected under subsection (a) in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.33§ 3, 96 Stat. at 134 (amending section 2(b)).

Subsection (b) also provided a non-exclusive factor for courts to consider: “The extent to which members of a protected class have been elected to office in the State or political subdivision is one circumstance which may be considered . . . .”34Id. However, subsection (b) limited itself by declining to establish a right to proportional representation for minorities.35Id. In other words, subsection (b) set the stage for the Court to tackle racial gerrymandering at the congressional level, which came only four years later with Gingles.

B. Gingles and the Majority-Minority Preconditions

The Court fulfilled Congress’s desire to protect voting rights when it implemented subsection (b)’s “totality of circumstances” approach in Gingles.36See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 43 (1986). Between the enactment of subsection (b) and the Gingles decision, the Court addressed racial redistricting in 1983 when it issued Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983). In that case, the Court rejected New Jersey’s congressional maps because its population deviations between districts “were not functionally equal as a matter of law,” and “the plan was not a good-faith effort to achieve population equality using the best available census data.” Karcher, 462 U.S. at 730–31, 744 (first citing Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394 U.S. 526, 532 (1969); and then citing Swann v. Adams, 385 U.S. 440, 443–44 (1967)). The Court’s application ultimately gave birth to the majority-minority district framework that continues to dominate racial redistricting post-Allen.

In Gingles, the Court grappled with a claim from a group of black citizens (“plaintiffs”) in North Carolina that alleged seven of the state’s legislature districts, one single-member and six multi-member, “impaired black citizens’ ability to elect representatives of their choice in violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and of [Section Two.]”37Gingles, 478 U.S. at 34–35 (1986). Applying the totality of circumstances approach from subsection (b), the district court concluded that all seven districts violated Section Two.38Id. at 37–38.

Justice Brennan, writing for the majority, acknowledged that subsection (b) responded to Bolden before providing a detailed analysis of subsection (b)’s legislative history and establishing three preconditions aimed at identifying redistricting schemes with a discriminatory impact.39Id. at 35–37, 43–44 (“[Congress] dispositively reject[ed] the position of the plurality in [Bolden], which required proof that the contested electoral practice or mechanism was adopted or maintained with the intent to discriminate against minority voters.” (citation omitted)). A majority of Justices joined Justice Brennan for the analysis discussed in this section. Id. at 34. The three “necessary preconditions” in Gingles for proving voter dilution under Section Two are: (1) the existence of a “sufficiently large and geographically compact [minority group] to constitute a majority in a single-member district”; (2) “the minority group must be able to show that it is politically cohesive”; and (3) “the minority must be able to demonstrate that the white majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it . . . usually to defeat the minority’s preferred candidate.”40Id. at 50–51. The last precondition, which explores racially polarized voting, “requires discrete inquiries into minority and white voting practices.”41Id. at 56. Justice Brennan contended that if “a significant number of minority group members usually vote for the same candidates,” then the plaintiff demonstrated a politically cohesive voting bloc necessary to a vote dilution claim under Section Two.42Id. Justice Brennan did not clarify what made a voting bloc politically cohesive. Due to the fact-intensive nature of each claim, “no simple doctrinal test” exists for determining a “legally significant racial bloc.”43Gingles, 478 U.S. at 58. However, “a pattern of racial bloc voting that extends over a period of time” serves as a key sign that “a district experiences legally significant polarization . . . .”44Id. at 57.

Applying the new preconditions to the North Carolina state legislature districts, Justice Brennan concluded that six of the seven districts violated Section Two.45See id. at 80. First, Justice Brennan relied on the district court’s conclusion “that at the time the multimember districts were created, there were concentrations of black citizens within the boundaries of each that were sufficiently large and contiguous to constitute effective voting majorities in single-member districts . . . .”46Id. at 38. Accordingly, the plaintiffs satisfied the first precondition.47See id. at 61.

Second, Justice Brennan concluded that the “black support for black candidates in [five of the six] multimember districts at issue here clearly establish the political cohesiveness of black voters.”48House District 23 was the lone outlier of the multi-member districts. Id. at 58–59, 60. Justice Brennan and the district court based their conclusion on data from sixteen elections over three years.49Gingles, 478 U.S. at 59, 61. The trend across elections demonstrated a consistency of “black support for black candidates rang[ing] between 71% and 92%,” with “black support for black Democratic candidates [in the general elections] rang[ing] between 87% and 96%.”50Id. at 59. Therefore, the plaintiffs satisfied the second precondition.51Id. at 61.

Lastly, to address the third precondition, Justice Brennan observed in six of the seven districts that “black voters have enjoyed only minimal and sporadic success in electing representatives of their choice.”52Id. at 60. That lack of success came from white support for black candidates ranging “between 8% and 50%” in primary elections and “28% and 49%” in general elections.53Id. at 59. Further, “81.7% of white voters did not vote for any black candidate in the primary elections.”54Id. In the general elections, “white voters almost always ranked black candidates either last or next to last in the multicandidate field, except in heavily Democratic areas where white voters consistently ranked black candidates last among the Democrats.”55Gingles, 478 U.S. at 59. Only one district, House District 23, saw proportional representation because “a black citizen [won election for] each 2-year term to the House . . . .”56Id. at 41. Accordingly, the plaintiffs satisfied the third precondition, allowing the Court to conclude that six of the seven challenged districts, House District 23 being the only compliant district, violated Section Two.57See id. at 80. Whether House District 23 violated Section Two was the central conflict between Justice Brennan’s majority opinion and Justice Stevens’s partial dissent. Justice Stevens argued that the election of one black candidate did not create “some sort of a conclusive, legal presumption” because the text of the statute and the legislative history did not support such a presumption. Id. at 106 (Stevens, J., dissenting in part). Rather, the “evidence of candidate success . . . is merely one part of an extremely large record.” Id. Justice Brennan never considered taxation in his Gingles analysis.

Justice White concurred and disagreed with Justice Brennan’s use of voter race to satisfy the preconditions.58Id. at 83 (White, J., concurring). He reasoned that “[u]nder this test, there is polarized voting if the majority of white voters vote for different candidates than the majority of the blacks, regardless of the race of the candidates.”59Id. Justice White also took issue with the second precondition’s lack of political cohesion parameters. The broad usage of political cohesion would act as an overinclusive standard and capture districts where the majority of a racial minority voted for a candidate but failed to elect their preferred candidate because the group failed to coalesce sufficiently around that candidate.60Id. Justice O’Connor, joined by three other Justices, concurred only in judgment.61Gingles, 478 U.S. at 83 (O’Connor, J., concurring in the judgment). With a majority of Justices backing Justice Brennan’s interpretation of Section Two, the Gingles preconditions carried binding power on lower courts and would alter the landscape of Section Two and Fourteenth Amendment claims.

C. Redistricting Jurisprudence Between Gingles and Allen

In the thirty-seven years separating Gingles and Allen, Supreme Court redistricting jurisprudence evolved to showcase a conflict between the Gingles preconditions and the Fourteenth Amendment.

Seven years after Gingles, the Court issued Shaw v. Reno,62509 U.S. 630 (1993). which dealt with the conflict between the Gingles preconditions and the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause.63Id. at 653–55; see Cooper v. Harris, 581 U.S. 285, 322–23 (2017) (holding that racial considerations predominated North Carolina’s 2011 redistricting maps, rendering them in violation of Section Two). Shaw required the Court to analyze two majority-minority districts that the plaintiffs, a group of North Carolina voters, alleged the state legislature created “to assure the election of two black representatives to Congress” without considering “‘compactness, contiguousness, geographical boundaries, or political subdivisions.’”64Shaw, 509 U.S. at 637 (quoting Appendix to Jurisdictional Statement 102a). Specifically, “the deliberate segregation of voters into separate districts on the basis of race violated [the plaintiffs’] constitutional right to participate in a ‘color-blind’ electoral process.”65Id. at 641–42. Writing for the majority, Justice O’Connor noted that the Court “never has held that race-conscious state decision-making is impermissible in all circumstances.”66Id. at 642. However, if a redistricting scheme could be seen as an attempt only to segregate the races without regard to traditional districting principles, then it violates the Fourteenth Amendment.67Id. Unlike the Gingles preconditions, which require a redistricting body to draw certain districts based entirely on race so that a majority-minority district covers a protected population,68Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50 (1986). Shaw restricts race-based redistricting only to instances where a compelling justification exists, otherwise known as strict scrutiny.69Shaw, 509 U.S. at 642–44.

The Supreme Court clarified its conclusion from Shaw two years later in a similar case, Miller v. Johnson.70515 U.S. 900 (1995). In Shaw, the Court did not specify how much race could influence a redistricting scheme.71See id. at 912–13 (citing Shaw, 509 U.S. at 644, 649, 657). Miller filled that gap: To prove that a redistricting scheme predominantly relied on race and violates the Fourteenth Amendment, “a plaintiff must prove that the legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral districting principles, including but not limited to compactness, contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions or communities defined by actual shared interests, to racial considerations.”72Id. at 916. The Court then used the clarified Shaw standard to reject the Department of Justice’s (“DOJ’s”) attempt to require Georgia to draw a third majority-minority district because the state’s previous plan, which already included two majority-minority districts, did not violate the Voting Rights Act.73Id. at 923. The Court criticized the DOJ’s “policy of maximizing majority-black districts” rather than combatting discriminatory redistricting schemes.74Id. at 924. Therefore, a third majority-minority district would subordinate traditional districting principles by “creating as many majority-minority districts as possible,” which violates the Fourteenth Amendment.75Id. (quoting Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130, 141 (1976)). The Court did not discuss the presence of racially conscious redistricting and how it could conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.76Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi, Expressive Harms, “Bizarre Districts,” and Voting Rights: Evaluating Election-District Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92 Mich. L. Rev. 483, 496 (1993) (“At least to the extent race consciousness arises in connection with VRA compliance, Shaw appears to accept it.”).

The Gingles preconditions allow for race-conscious redistricting, which potentially conflicts with the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause analyses as applied by the Court in Shaw and Miller. The Court revisited Section Two when a group of black voters challenged Alabama’s congressional districts following the 2020 Census.77See Allen v. Milligan, 143 S. Ct. 1487, 1502 (2023). The three initial cases, consolidated as one, arrived at the Supreme Court as Allen v. Milligan.

D. Allen Affirms the Gingles Preconditions

When Alabama began its redistricting process following the 2020 Census, its legislature passed a map that largely resembled the 2011 map, which included only one majority-minority district out of seven total districts.78See id. The plaintiffs, three groups of Alabama voters, all brought claims under the VRA’s Section Two and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.79Id. In his description of the Gingles preconditions, Chief Justice Roberts noted that a district may satisfy the first precondition’s contiguity and compactness requirement “if it comports with traditional districting criteria” but did not mention taxation as a possible evaluation measure.80Id. at 1503. When evaluating the district court’s decision, the Court rejected Alabama’s argument, defending its maps as keeping traditional communities of interests together, such as the Gulf Coast region.81Id. at 1504–05. In its rejection, the Court noted only two witnesses testified that the Gulf Coast was a community of interest, despite those witnesses noting that splitting the Gulf Coast would diminish the influence of areas like Mobile County.82Id. at 1505. The Court identified another key community of interest in its rejection of Alabama’s argument: the Black Belt, named for its fertile soil.83Allen, 143 S. Ct. at 1505. The rural and impoverished region with poor healthcare and lack of access to government services stretches across the southern part of the state from the western border to Montgomery.84Id.

The Court then shifted its focus to “Alabama’s attempt to remake our [Section Two] jurisprudence anew” by introducing a race-neutral benchmark that uses modern technology to create millions of districts that comply with traditional voting criteria while not considering race.85Id. at 1506. The algorithm determines the number of majority-minority districts that exist and calculates the average number that becomes the race-neutral benchmark.86Id. Alabama then argued that this race-neutral benchmark best matches the text of the Voting Rights Act because it eliminates any barriers to voting on account of race by never using race as a redistricting factor.87Id. However, because Gingles looks at whether a map could have a disparate effect based on race and then determines whether such a disparate effect could happen, the Court concluded that whether Alabama’s map aligns with a race-neutral benchmark is irrelevant because it is only one factor in the totality of circumstances approach.88Id. at 1507–08.

Ultimately, the majority rejected Alabama’s appeal, in part because (1) it would require overruling Gingles; and (2) Section Two caselaw does not require redistricting bodies to ignore race completely.89See Allen, 143 S. Ct. at 1512. Rather, maps cannot predominantly use race as a factor, regardless of whether discriminatory intent exists.90See id. If Alabama disapproves of the Court’s jurisprudence, then it should lobby Congress to make the appropriate changes.91Id. at 1515 (noting that “Congress is undoubtedly aware” of the Court’s precedent and “can change that if it likes”). Otherwise, stare decisis requires the Court to keep the status quo.92Id. (stating that “until and unless” Congress changes the law, “statutory stare decisis counsels our staying the course”).

In his concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh reinforced the Court’s use of stare decisis, leaving to Congress the responsibility of updating and correcting erroneous statutory precedents; a task which, he noted, Congress and the president have not done with Section Two in the thirty-seven years following Gingles.93Id. at 1517 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring in part).

Justice Thomas, along with Justices Gorsuch, Barrett, and Alito, dissented, contending that Section Two does not demand proportional representation of minority voters in a state’s congressional delegation.94Allen, 143 S. Ct. at 1523 (Thomas, J., dissenting). Justice Thomas criticized the Court for using stare decisis to uphold a line of cases based on Gingles’s incorrect statutory construction that lacks principled application four decades later.95Id. at 1520–21. In short, Justice Thomas criticized the majority opinion as enabling the continued “racial balkanization” throughout the country in the form of redistricting using race classifications.96Id. at 1521. Alabama could not feasibly adopt a map where District Two, the new majority-minority district, connects parts of the Black Belt with residents of the Montgomery metropolitan area and the black residents of the Mobile metropolitan area, leaving just enough black residents in the Black Belt and Birmingham to create another majority-minority district without using a racially-motivated goal.97Id. at 1527. District Two must take this shape because the Black Belt—300,000 black residents—cannot create a majority in a single congressional district without Montgomery or Mobile.98Id. at 1528. The shape of the two majority-minority districts, then, was drawn with race as a predominant factor to satisfy the Gingles preconditions in a way that violates the Fourteenth Amendment.99See id. at 1521 (“[Stare decisis] should not rescue modern-day forms of de jure racial balkanization—which, as these cases show, is exactly where our [Section Two] vote-dilution jurisprudence has led.”). Regardless, the 6-3 Allen decision kept the Gingles preconditions untouched.

II. Gingles, Allen, and the Conflict Between Section Two and the Fourteenth Amendment

Alabama has an extensive history of racial discrimination that requires a remedy.100As the Allen majority noted, Alabama failed to elect a black representative to Congress for 115 years after Reconstruction. Allen, 143 S. Ct. at 1501. However, Gingles is the wrong solution because it requires redistricting using race as a predominant factor while lacking a compelling factor fit to satisfy the “strictest scrutiny” reserved for race discrimination, which creates a contradiction between Section Two and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.101See Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630, 643, 650 (1993) (observing that the Supreme Court previously “held that the Fourteenth Amendment requires state legislation that expressly distinguishes among citizens because of their race to be narrowly tailored to further a compelling governmental interest.”). This twofold problem arises solely from the failure of the Gingles preconditions to balance diversity with fair districts and the Supreme Court’s unfortunate use of stare decisis to keep the preconditions in place.

This Part provides a brief overview of the problem at the heart of this Comment’s tax-based solution—the conflict between Section Two and the Fourteenth Amendment—by reviewing several critiques made by other legal scholars. This Part then reviews other proposed solutions that address the shortfalls of Section Two, and ends by revisiting Justice Thomas’s criticisms of the majority in Allen and Section Two.

A. Analyses and Critiques of Section Two’s Fairness

While most scholarship does not advocate for replacing Gingles with a race-neutral standard advocated by Alabama and the dissent in Allen, many have critiqued and noted weaknesses in Section Two while reinforcing its necessity. None, however, mention taxation as a solution. For example, Nicholas Stephanopoulos and Jowei Chen concluded that if the Supreme Court gutted Section Two, most states would have fewer majority-minority districts and potentially reduce the number of minority candidates elected to Congress.102Jowei Chen & Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, The Race-Blind Future of Voting Rights, 130 Yale L.J. 862, 918–19 (2021). In another article, Stephanopoulos observes that despite Section Two’s success in increasing the number of minority legislators for black voters, it has failed to yield any change for Hispanic voters.103Nicholas O. Stephanopoulos, Race, Place, and Power, 68 Stan. L. Rev. 1323, 1330 (2016). Section Two’s failure to increase all minority representation, rather than just black representation, further advocates the need for a new Section Two test that puts fair and representative districts first while ensuring congressional diversity.104But see Gilda R. Daniels, Racial Redistricting in a Post-Racial World, 32 Cardozo L. Rev. 947, 968 (2011) (concluding that Section Two should remain in place given the progress it made in ensuring equal participation for all voters in the electoral process).

Political considerations are seemingly absent throughout the Court’s jurisprudence on Section Two and the Fourteenth Amendment. However, the problem posed by Gingles and Allen does not necessarily involve any political implications because scholarship cannot even agree on whether Gingles and Allen benefit one political party over the other. On one side of the debate, Keisuke Nakao argues that majority-minority districts benefit Republicans because they favor Republican interests in packing minority voters into limited districts.105Keisuke Nakao, Racial Redistricting for Minority Representation Without Partisan Bias: A Theoretical Approach, 23 Econ. & Pol. 132, 133 (2011). In this Comment, the term “packing” means “concentrating minority voters in a single district to reduce their influence in surrounding districts.” Alexander v. S.C. State Conf. of the NAACP, 144 S. Ct. 1221, 1255 (2024) (Thomas, J., concurring in part). On the other side of the debate, Adam Cox and Richard Holden argue that Section Two “comes with a built-in partisan bias in favor of the Democratic party.”106Adam B. Cox & Richard T. Holden, Reconsidering Racial and Partisan Gerrymandering, 78 U. Chi. L. Rev. 553, 556 (2011). Regardless of whether Section Two benefits one political party over the other, gerrymandered districts that see fewer competitive elections offer fewer incentives for representatives to serve constituent economic interests.107See Sahil Raina & Sheng-Jun Xu, The Effects of Voter Partisanship on Economic Redistribution: Evidence from Gerrymandering 1–2 (Univ. of Alberta Sch. of Bus., Working Paper No. 2019-505, 2021), https://perma.cc/JH55-7HQ7. Any replacement to the Gingles preconditions that incidentally benefits one political party over the other fails Section Two’s purpose of ensuring congressional diversity. Therefore, a replacement to the Gingles preconditions must rely on a politically neutral standard that allows naturally competitive districts to form and ensure attentive representation.

B. The Failure to Find a Unifying Solution

While scholars have proposed several solutions to Section Two’s shortfalls, no single solution has garnered unified support. The lack of unity partly results from a failure to agree on defining communities of interest.

One solution, proposed by Notre Dame law student Ben Boris, advocates for modifying the first Gingles precondition—the existence of a sufficiently large and geographically compact minority to constitute a majority in a single-member district—to recognize coalition districts, where a minority elects their preferred candidate with the aid of other demographics.108Ben Boris, Note, The VRA at a Crossroads: The Ability of Section 2 to Address Discriminatory Districting on the Eve of the 2020 Census, 95 Notre Dame L. Rev. 2093, 2100, 2104 (2020). Boris argues that courts should recognize coalition districts when applying Section Two or the Fourteenth Amendment, but such an application requires a new standard to achieve fair districts.109Id. at 2117. This Comment’s solution echoes Boris’s call for coalition districts, as the majority-minority district incidentally created by the tax approach in Alabama is a coalition district.110See infra note 142. While Boris’s article took a step in the right direction, it did not alter the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Allen.

The lack of solutions partly results from disputes on how to build redistricting maps. J. Gerald Hebert argues that redistricting bodies should use census tracts and precincts as the building blocks for new districts.111J. Gerald Hebert, Redistricting in the Post-2000 Era, 8 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 431, 463 (2000). Maps based on precincts or census tracts should then, says Hebert, receive a presumption of constitutionality from courts because using precincts and census tracts essentially “guarantees that the resulting district will not signal that race was the overriding factor in a state’s redistricting calculus.”112Id. (emphasis omitted). Hebert does not mention the use of taxation in his article.

While the natural extension of Hebert’s thought would require using municipal and county lines as the guiding principle for redistricting, most scholars reject the idea. For instance, while proposing two quantifiable standards to identify communities of interest, Sanda J. Chen and her five co-authors reject using municipal and county lines to define communities of interest because residents identify with their home municipality or county to varying degrees.113See Sandra J. Chen, Samuel S.-H. Wang, Bernard Grofman, Richard F. Ober, Jr., Kyle T. Barnes & Jonathan R. Cervas, Turning Communities of Interest into a Rigorous Standard for Fair Districting, 18 Stan. J.C.R. & C.L. 101, 113, 125 (2022) (noting that “the degree to which residents identify with county and neighborhood units often varies, and preexisting government lines do not necessarily reflect meaningful communities”). Even Alec Ramsay, a principal behind Dave’s Redistricting (the redistricting platform that generated this Comment’s maps), argues that compact districts are not always fair because they do not necessarily reflect a state’s political geography.114Alec Ramsay, Compact Districts Aren’t Fair, Medium (Feb. 5, 2020), https://perma.cc/RH4U-78TD. While Ramsay presents a thoughtful argument and analysis that uses North Carolina and Pennsylvania as examples, his argument contributes to the problem of unfair districts by replacing race with political geography, another non-representative factor, diminishing common-denominator factors that should influence redistricting, such as industry and taxation.115Id. Notably absent from Ramsay’s article, along with the rest of the scholarship on Section Two and the Fourteenth Amendment claims to racial gerrymandering, is a discussion on whether a tax-based analysis can provide a fair and objective factor to base redistricting.

C. Justice Thomas and Section Two in Allen

The predominance of race that Gingles and Allen use to redraw maps violates the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which denies discrimination based on race.116See Allen v. Milligan, 143 S. Ct. 1487, 1539 (2023) (Thomas, J., dissenting). To illustrate this point, Justice Thomas noted in his Allen dissent that the plaintiffs needed to “radically transform[]” District Two to secure its second majority-minority district while engaging in “extreme racial sorting.”117Id. at 1526. He then described how District Two split the Gulf Coast community of interest and absorbed only the areas necessary to create a majority-minority district while District One, the original Gulf Coast district, now connects suburban and rural groups that lack “anything special in common” other than hosting predominantly white populations.118Id. Justice Thomas’s critique exposes the heart of the problem: Gingles’s and Allen’s interpretation of Section Two uses race, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, to create districts that unnaturally connect various communities that have only their race and home state in common.119See infra Appendix One. Justice Thomas made a similar point in his Alexander concurrence. Alexander v. S.C. State Conf. of the NAACP, 144 S. Ct. 1221, 1263 (2024) (Thomas, J., concurring in part) (“The Court’s standard for vote dilution claims is similarly flawed, because it requires judges to engage in racial stereotyping. . . . [T]he Constitution does not define a baseline of effective representation by which to evaluate the dilution of a vote.”).

If Gingles’s and Allen’s interpretation of Section Two provided a true remedy to racial redistricting, it would not further divide objective communities of interest to connect areas of the same race in violation of the Equal Protection Clause, which ultimately creates unfair legislative districts. This Comment seeks to solve that problem.

III. A Balancing Act: The Tax Approach

Solving the conflict between the Fourteenth Amendment and the Court’s Section Two analysis by balancing congressional diversity with fair, compact, and contiguous districts requires an objective approach not dependent on race. Rather, a court should look to a unifying factor for every voter in the United States: taxes. Every voter pays taxes, from property and sales taxes to millages imposed by a municipality. In turn, those voters benefit from the services the taxing government entity provides. Since every voter pays taxes and receives those services, grouping voters with these characteristics may make for fair districts.

This Comment’s tax approach for a court to evaluate allegedly discriminatory electoral maps requires a court to analyze the degree to which (1) the constituents of a district benefit from the same or similar tax-funded institutions; and (2) the district contains similar tax revenue sources. Under the first factor, a court would compare tax-funded institutions within a district, such as school districts, municipal services, hospitals, airports, large infrastructure projects, and recreational services. A district fails this factor if the tax-funded institutions serve different populations or differ significantly from each other without a compelling reason. For the second factor, a court would prefer keeping together regions with similar industries, such as agricultural, manufacturing, or white-collar firms. If a district combines two regions with contrasting industries when reasonable alternatives exist, then the district fails the second factor. A court may employ either question to varying extent based on the nature of the contested districts.

This Part provides a detailed explanation of the tax approach to evaluating discriminatory maps. The entire application and analysis uses electoral and demographic data from Dave’s Redistricting, so this Part first explains how the platform calculates its data and how it impacts this Comment’s analysis. This Part then describes and applies the tax approach to draw a new map for Alabama’s congressional districts. Ultimately, this Part proves that the tax approach harmonizes the Fourteenth Amendment with Section Two while balancing congressional diversity with fair, compact, and contiguous districts.

A. Data Methodology

Every map created for this Comment uses Dave’s Redistricting, a redistricting platform using demographic and political data for every state.120About DRA, supra note 10. The demographic and political data on Dave’s Redistricting form an integral part of this Comment’s application of the tax approach. This Section explains where the data comes from and how this Comment uses the data in its maps.

Dave’s Redistricting has demographic data from the 2020 Census obtained directly from the United States Census Bureau, which includes total population numbers that determine the size of this Comment’s districts.121Id. Using the total population numbers, the 2020 precinct shapes are disaggregated using the 2019 and 2020 American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates.122Id. American Community Survey Five-Year Estimates are ongoing surveys conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau to provide social, economic, housing, and demographic data useful in community decision-making. American Community Survey 5-Year Data (2009–2022), U.S. Census Bureau (Dec. 7, 2023), https://perma.cc/TE9M-5YDY.

Dave’s Redistricting provides election data through its partners, the Voting and Election Science Team and the Redistricting Data Hub.123In accordance with its licensing agreements, Dave’s Redistricting provides a full list of its data partners in its election and demographic data description. About Data, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/UGW8-A2LP. All citations in this Comment referring to Dave’s Redistricting data do so with the understanding that the data originates from one of Dave’s Redistricting’s data partners. For Alabama, Dave’s Redistricting credits the Voting and Election Science Team (“VEST”) (2016-2020) and Redistricting Data Hub (2022) for its demographic and electoral data. Id.; see also Dave’s Redistricting Terms of Use, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/EZ5X-LBQY (providing additional copyright information); About Our Data, Redistricting Data Hub, https://perma.cc/LR8G-DA69 (providing additional information about Redistricting Data Hub’s data methodology). For more information on the VEST, see Precinct Data, Univ. of Fla. Election Lab, https://perma.cc/6J26-7Y3Q. This Comment uses Alabama’s 2016–2022 Composite, which takes the mean of the 2016 and 2020 U.S. Presidential elections, the 2020 and 2022 U.S. Senate elections, and the 2018 and 2022 state governor and state attorney general elections.124About Data, supra note 123; Alec Ramsay, Election Composites, Medium (Feb. 7, 2020), https://perma.cc/U9B9-JC84. The composite data provides the most accurate depiction of a state’s electoral makeup because it shows underlying voter patterns.125Ramsay, supra note 124. In contrast, using only one election merely shows a single variation of those underlying patterns.126Id. Dave’s Redistricting excludes any uncontested elections.127Id.

The method behind calculating Alabama’s 2016–2022 Composite remains susceptible to shifting because of one election. For instance, Alabama’s 2016–2022 Composite electoral data shifted to the right by 4.5 points (59.4% to 63.9% Republican voting share statewide)128Compare Alabama 2022 Composite, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/WJX9-9PAL, with Alabama 2020 Composite, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/WX34-W7Z7. Composite electoral data is located under the “District Details” dropdown tab on the left menu of each web page. because of the inclusion of the 2022 midterm election results, which saw a strong Republican outcome, and the exclusion of the 2017 special Senate election, which saw a Democratic upset.129Alabama Election Results, Bloomberg (Nov. 28, 2022, 2:47 PM), https://perma.cc/4W3R-B2FB; Kim Chandler & Steve Peoples, Democrat Jones Wins Stunning Red-State Alabama Senate Upset, AP News (Dec. 13, 2017, 12:56 AM), https://perma.cc/5X7Y-MVEB. Nonetheless, the 2016–2022 Alabama Composite, alongside the demographic data from the 2020 Census, provides the best support for this Comment’s application of the tax approach.

B. The Tax Approach

All taxes are imposed on the populace for a public purpose.13016 McQuillin, The Law of Municipal Corporations § 44:43 (3d ed.), Westlaw (database updated July 2024). Representatives are most responsive to the public they serve, which is best indicated by the taxes generated and the benefits received by a district’s populace.131See id. According to James Madison, the House of Representatives must share an immediate dependence with the people: “As it is essential to liberty that the government in general should have a common interest with the people, so it is particularly essential that the [House of Representatives] should have an immediate dependence on, and an intimate sympathy with, the people.”132The Federalist No. 52 (James Madison). Taxation, not race, best unites a representative and his constituents to ensure the representative has an immediate dependence on his constituents to provide redress to the most pressing and appropriate issues: promoting industry and improving taxpayer-funded institutions, both within the realm of a representative’s duty as a mediator between government and constituents. These principles serve as the bedrock for the tax approach and reinforce taxation as the best standard to evaluate whether a legislative map discriminates against any minority. While taxation does not perfectly capture American communities as “We the People,” it does represent a realm of near-exclusive government control, making taxation one of the most prominent, uniform interests a court should use to analyze legislative maps.

The tax approach determines whether a district discriminates against a racial minority by analyzing the degree to which (1) the constituents of a district benefit from the same or similar tax-funded institutions, and (2) the district contains similar tax revenue sources. Each factor serves a distinct purpose to guide how a court analyzes the districts. Both factors look to state and local taxes to identify similar tax revenue sources and tax-funded institutions.

The first factor—the degree to which the district contains the same or similar tax-funded institutions—keeps districts compact and similar counties or municipalities together. Incidentally, this factor requires minimal county or municipal splits unless a redistricting body can show good cause, such as fulfilling population requirements or ensuring a municipality remains intact if split by a county line.133While not at issue in redrawing Alabama, preserving a full city within one electoral district is the tax approach’s priority, even if that means splitting counties. For instance, a redistricting body redrawing Michigan’s legislature maps would split Ottawa and Allegan counties to keep the City of Holland—which straddles the county line—together. Splitting is necessarily reduced because the first factor presumes that each county is its own community of interest. Despite Sandra Chen’s work disclaiming that counties and municipalities serve as an adequate identifier for a community of interest, taxpayer residents of one county or municipality usually fund the same local services and institutions, such as: (1) police; (2) parks and recreation departments; (3) schools; (4) roads; (5) drinking, drainage, and sewage facilities; (6) libraries; and (7) transportation services.134This list of public services is not exhaustive. See Chen et al., supra note 113, at 113, 125; see also, e.g., Ala. Const. art. XI, § 216.01 (authorizing various municipalities to impose additional taxes “for any special purpose or purposes”) and art. XIV, § 269 (authorizing counties to levy a tax to support their public school systems). The size of a tax base is also a relevant factor for the first factor. Whether one resident identifies with their county or not is irrelevant: The taxes they pay and the government services they receive define their community of interest.

For instance, the Metro Area Express bus system, operated by the Birmingham Jefferson County Transit Authority (“BJCTA”), offers sixteen routes serving Birmingham City and the surrounding area, including Jefferson County.135Mission and Vision, Max Transit, https://perma.cc/MCN6-99YZ; Routes, Max Transit, https://perma.cc/7H44-3PTZ. Outside of federal funds, BJCTA is also supported by local grants, the beer tax, ad valorem taxes, and municipality taxes.136Mission and Vision, supra note 135. Under the first factor, the taxes that support BJCTA justify keeping Birmingham City and Jefferson County together so that its congressional representative can prioritize securing federal funding for BJCTA.

While keeping counties and cities intact makes the tax approach vulnerable to Alec Ramsay’s criticism by not reflecting political geography,137See Ramsay, supra note 114. such a district shape enables its representative to focus solely on that municipality’s or county’s needs because a reduced chance of conflicting intra-district interests exists. If a district encompasses more than one county or municipality, then that representative can more easily prioritize interests among the counties because they likely have similar needs as indicated by each county’s or municipality’s tax revenue sources and tax-funded services. Therefore, a redistricting body cannot discriminate against minority-race voters and deprive them of adequate representation because their representation is based on the character of the government services they receive. If the government services are poor or inaccessible in an area like Alabama’s Black Belt, then that area represents a community of interest that a redistricting body must keep together under the first factor. A representative elected from that district then has the incentive to address the poor government services since that interest dominates the district. Districts that encompass counties with significantly different tax-funded institutions—and, therefore, potentially conflicting interests—would fail the first factor.

To determine whether a district satisfies the first factor, a court would look at the quality and size of the tax-funded institutions. For instance: Are the school districts in the district of similar quality and size? Do the residents of a district have equal access to government services? Do the institutions that benefit from public grants, such as hospitals and transportation networks, benefit the same or similar-sized populations? Are there any unique tax-funded institutions that provide services to an entire region? If so, does the district cover most residents who fund that institution with their taxes?

While this is a non-exclusive list of questions a court may ask, the questions do not necessitate hard quantitative analysis alone but require a mix of localized knowledge with a quantitative tracing of dollars from the taxpayer to the tax-funded institution. Given the large size of congressional districts, especially in states with a small or medium-sized population, like Alabama, a quantitative analysis is likely unnecessary. Instead, courts would place a greater weight on localized knowledge—meaning the understanding of how the state is culturally divided, what makes each part of a state unique, and the challenges each region faces. However, disputes over a state legislative map may require hard quantitative analysis since districts will often split counties and cities given their smaller size. Regardless of the questions raised by the first factor, the generalized nature allows for more than one district to suffice so long as it does not disrupt significant communities of interest, often defined by the taxes imposed and spent within counties and municipalities.

The second factor—whether the district contains similar tax revenue sources—prevents a redistricting body from combining an urban area large enough to constitute its own district with a rural area. Large urban areas often do not share the same characteristics as rural areas. For example, rural areas often rely on agricultural industries, such as farming and ranching. On the other hand, urban areas lack the space needed for farming and ranching, and often host industries such as white-collar firms or large-scale manufacturing. By keeping similar industries together, a representative is incentivized to promote that industry further, given its dominance in the district. Likewise, the second factor prevents a redistricting body from cracking urban areas and covering rural areas.138See infra Appendix 1 (showing several Illinois districts that crack Chicago and cover large swaths of rural areas, which disenfranchises rural voters). In this Comment, the term “cracking” means “splitting a group of minority voters between multiple districts to avoid strong minority influence in any one district.” Alexander v. S.C. State Conf. of the NAACP, 144 S. Ct. 1221, 1255 (2024) (Thomas, J., concurring in part). Since this Comment advocates for applying the tax approach in the context of Section Two or Fourteenth Amendment claims, the cracking concern takes a less prevalent interest given its primary use for political disenfranchisement.139See infra Appendix 1 (showing that those same Illinois districts are reliably Democratic).

Together, the two factors ensure each district provides a strong and inclusive identity that incentivizes its representative to focus on those interests. More effective than ensuring one race constitutes a majority in a single district, following the tax approach will ensure fair districts that provide the opportunity for quality representation while preserving diverse congressional delegations. In other words, taxes serve as a neutral indicator of communities of interest best fit to use as a basis for redistricting, which happens to coincide with county and municipal boundaries.

Many scholars will likely criticize the tax approach as too broad, which would enable a court, or a redistricting body, to use its discretion to discriminate against minority voters. If true, the tax approach would fail to protect minority voters from discrimination. This critique finds strength in the race-blind nature of the tax approach and that the approach does not necessitate a quantitative analysis. What, then, will protect minority voters from racial gerrymandering?

The tax approach replaces race with tax as the common denominator for constitutional districts. Since the tax approach is race-blind, it does not guarantee majority-minority districts: It is not designed to do so. Rather, the first factor forces redistricting bodies and courts to keep similar counties and municipalities together to form tax-based communities of interest. The second factor also keeps similar counties and municipalities together by preventing a redistricting body from splitting areas with common industrial interests characterized by tax revenue sources. For instance, as illustrated in the next section, the tax approach necessitates the Black Belt remain together given its counties’ similar tax-funded institutions, albeit with poor access. If a redistricting body split the Black Belt, the district would violate the first factor unless it contains similar tax-funded institutions. If the redistricting body succeeds in making that showing, then the representative for that district has adequate incentive to represent all its constituents since they have a common interest in improving the low-quality tax-funded institutions. Through taxation, a district becomes one. The tax approach’s broad nature enables a court to analyze such districts while granting enough flexibility to the redistricting body to allow for a map that reflects localized interests.

C. Applying the Tax Approach to Alabama’s Congressional Districts140While this Comment applies the tax approach only in the context of redrawing Alabama’s congressional districts following a Section Two and a Fourteenth Amendment claim, a state supreme court may adopt this standard to evaluate the political fairness of a state’s redistricting map. See Rucho v. Common Cause, 139 S. Ct. 2484, 2506–07 (2019).

Since Allen focused on Alabama’s redistricting efforts at the congressional level, this Comment draws a new congressional map for Alabama to demonstrate the appearance of a compliant map and how a court might analyze a map with the tax approach. This Section presents a new map and table showing demographic and political data relying on the composite data for 2016–2022. This Section then explains the interests represented in each district and how applying the tax approach prevents discrimination and fulfills the goals of Section Two and the Fourteenth Amendment. In doing so, this Comment does not allege that the map below is the only map that would satisfy the tax approach or that the map is perfect. Rather, this map is only one example that complies with the tax approach and the Author’s discretion when a district must join two or more tax-based communities of interest.

Figure 4: Alabama Congressional Districts (Tax Approach)141Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2022 Composite: Map, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/3G69-VUTJ.

| Tax Approach Alabama Map 2016–2022 Composite142 Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2022 Composite: Statistics, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/BRS7-NLLB. Population Deviation is calculated by multiplying a district’s “Total population” by its “Deviation % from total population”—found in the linked data—and rounding to the nearest whole number. For the Partisan Advantage calculation, see supra note 11. | ||||

| District | District Population | Population Deviation | Minority Population Percentage | Partisan Advantage

(|R – D|) |

| One | 718,493 | 718 (.10%) | 34.00% | R + 32.04% |

| Two | 717,977 | 215 (.03%) | 47.87% | D + 5.58% |

| Three | 718,404 | 647 (.09%) | 50.65% | R + 4.43% |

| Four | 718,634 | 862 (.12%) | 34.64% | R + 37.99% |

| Five | 716,978 | -789 (.11%) | 29.19% | R + 32.52% |

| Six | 720,922 | 3,172 (.44%) | 17.38% | R + 65.83% |

| Seven | 712,871 | -4,848

(-.68%) |

27.85% | R + 44.29% |

The absolute population equality for each district is 717,754.143Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2022 Composite: Statistics, supra note 142. Dividing Alabama’s total population of 5,024,279 persons—as reported by the 2020 Census—into seven equally populated districts and rounding to the whole person produces seven districts of 717,754 persons each. QuickFacts: Alabama, U.S. Census Bureau, https://perma.cc/3EVV-X33N (listing the 2020 Census figure under “Population, Census, April 1, 2020”). The maximum population deviation between the districts is 1.12%—the deviation between Districts Six and Seven—which Dave’s Redistricting criticizes for being above the generally accepted court threshold of 0.75%.144Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2022 Composite: Statistics, supra note 142. However, instead of a hardline rule at 0.75%, caselaw supports a fact-intensive “as nearly as practicable” standard145Kirkpatrick v. Preisler, 394 U.S. 526, 527–28, 530–31 (1969) (quoting Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 577 (1964)). that allows for deviations from absolute population equality to serve a legitimate state interest, such as respecting municipal boundaries.146Tennant v. Jefferson Cnty. Comm’n, 567 U.S. 758, 759–60, 761–62 (2012) (per curiam) (noting that the “as nearly as practicable” standard does not mean “precise mathematical equality”; a legitimate state interest includes respecting municipal boundaries, and the state’s burden to show its interest is flexible and dependent on a fact-intensive analysis (quoting Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725, 730 (1983)) (internal citation omitted)). Since the 1.12% population deviation between Districts Six and Seven ensures only two county splits exist, the deviations serve to respect municipal boundaries and would likely pass scrutiny by a court.147See id. at 762. Even if a court struck the map because of the general deviation, the remedy would require District Six to consume more of Marshall County from District Five and another county split between Districts Seven and Four or Two. District Seven could also reduce its deviation by splitting a precinct in Shelby County with District Two.

Districts One, Two, and Three, respectively, cover the Gulf Coast, Birmingham/Jefferson County, and the Black Belt, which the Allen dissent acknowledges as communities of interest.148Allen v. Milligan, 143 S. Ct. 1487, 1525, 1527, 1531, 1528 (2023) (Thomas, J., dissenting) (describing the districts and conceding for purposes of the argument that the Gulf Coast and Black Belt are communities of interest); see id. at 1528 (noting the concentrated urban quality of Birmingham and surrounding Jefferson County). The map contains two county splits: Shelby County between Districts Two and Seven and Marshall County between Districts Five and Six. Both county splits result in maintaining each district population within one percent of absolute equality.

District One remains relatively unchanged from the original congressional map and contains Mobile, Baldwin, Washington, Monroe, and Escambia Counties. Unlike Livingston County Plan Three and the special master’s Remedial Plan Three, the tax approach addresses Justice Thomas’s concerns by keeping the Gulf Coast community together, with the Mobile metropolitan area serving as an undisturbed population center.149Id. at 1526. Under the first factor of the tax approach, the Gulf Coast should remain connected to keep representation for the following under one representative: (1) tax-funded infrastructure projects unique to Mobile, such as the system of pier and dock works, along with channels of Mobile Bay as documented by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and various local fishing guides, and (2) the United States Coast Guard’s Aviation Training Center, which serves as one of the largest non-industrial employers in Mobile.150A non-exclusive list of the docks and piers in the Mobile region includes Cedar Point Pier (Mobile County), Dauphin Island Pier (Mobile City), Bayou La Batre Pier (Bayou La Batre City), and Orange Beach Pier (City of Orange Beach). See, e.g., Cedar Point Pier, Mobile Cnty., https://perma.cc/V9ED-MDEC; 8 Best Fishing Piers in Mobile Alabama, Dixon Fishing, https://perma.cc/HP7G-LL73; John Pike, Air Station Mobile, Glob. Sec., https://perma.cc/87QX-MVT6 (May 7, 2011, 2:53 AM). No other region of Alabama has access to the Gulf Coast, making these tax-funded institutions unique to the Mobile area and justifies keeping the Gulf Coast region intact in District One.

Under the second factor, the strong presence of oil alone justifies keeping the Gulf Coast community of interest together. Mobile is home to the Mobile Bay Oil Field, which includes roughly seventy oil platforms.151See Platforms in the Gulf of Mexico Map, Saltwater Recon, https://perma.cc/H7GH-J3PZ (Apr. 1, 2021, 8:02 AM); see also Mobile Bay Complex, W&T Offshore, https://perma.cc/QLW6-X423 (stating that independent oil and natural gas producer W&T Offshore, Inc., has drilled forty-five successful wells in the Mobile Bay Oil Field as of December 31, 2022). Except for the northern third of Monroe County, District One is housed entirely within the Southwest Alabama Region’s oil and gas producing area.152Alabama Oil and Gas Regions, Encyclopedia of Ala., https://perma.cc/8EWU-FR4M. The strong presence of the oil industry in the Gulf Coast region satisfies the second factor. Therefore, both factors support District One, keeping the Gulf Coast tax base intact.

District Two includes all of Jefferson County, home to Birmingham, and roughly 15,000 people from neighboring Shelby County. This district requires the least analysis from the tax approach because almost all of its residents pay state and local taxes that benefit the same institutions: the Jefferson County Library Cooperative which consists of forty libraries, the BJCTA that provides public transportation to the district’s population center, and the two public school districts: Jefferson County and Birmingham City Schools.153Public Libraries in Jefferson County, Jefferson Cnty. Libr. Coop., https://perma.cc/9BJS-FBA5; Mission and Vision, supra note 135; District Profile: Jefferson County School District, Jefferson Cnty. Schs., https://perma.cc/R8Y8-LW4Z; District Profile: About Birmingham City Schools, Birmingham City Schs., https://perma.cc/3W7K-JQA4. Since nearly every taxpayer of District Two benefits from the same or similar tax-funded institutions, District Two’s strong performance on the first factor alone infers success on the second factor because Jefferson County necessarily contains neighboring, and thereby similar, tax revenue sources, which allows the District to satisfy the tax approach.

District Three includes most of the Black Belt and its largest city, Montgomery.154See Alabama’s Black Belt Counties, Univ. of Ala. Ctr. for Econ. Dev., https://perma.cc/Q9RC-XPPD. District Three is the only coalition majority-minority district, with a minority population percentage of 50.65%: a necessary but incidental creation using the approach. As the Allen Court noted, the Black Belt, named for its dark and fertile soil, is plagued by poor access to government services and poverty.155Allen v. Milligan, 143 S. Ct. 1487, 1505 (2023) (Thomas, J., dissenting). The poor access to government services is a characteristic the first factor requires to remain intact. By grouping voters with poor access to government services, the first factor ensures that poor access is a dominant interest in the district, which incentivizes the representative to allocate resources to improving access to government services.

The Black Belt’s rural nature combined with the City of Montgomery (2020 Census population of 200,603), an urban area too small for its own congressional district, satisfies the second factor.156QuickFacts: Montgomery City, Alabama, U.S. Census Bureau, https://perma.cc/KXF2-XC2C (listing the 2020 Census figure under “Population, Census, April 1, 2020”). The taxpayers of District Three receive poor government services despite funding them through state and local taxes. Since District Three keeps nearly the entire Black Belt intact, its representative has a strong incentive to advocate for increased access to government services and rural agricultural services.157Given the abnormally strong performance of Republicans in 2022 compared to the Party’s less strong performance in 2020, this Comment refrains from making generalized political arguments regarding the political cohesion of minority voters in the Black Belt. See Alabama Election Results, supra note 129. Therefore, District Three passes the tax approach.

The rural Wiregrass Region of Southeast Alabama prevents District Three from including Russell and Barbour Counties, which form the eastern tip of the Black Belt.158See Wiregrass Region, Encyclopedia of Ala., https://perma.cc/2MPD-PUHX (providing a geographical description of Alabama’s Wiregrass Region). For District Three to encompass the Montgomery Metropolitan Area in the eastern portion of the Black Belt, it must extend across nearly the entire width of Alabama. This forces District Four, which includes the entire Wiregrass Region, to follow along the eastern border of Alabama to the next closest available area: Lee, Chambers, Tallapoosa, Coosa, and Talladega Counties. The inclusion or exclusion of certain counties in the next available area falls within the redistricting body’s discretion, so long as it satisfies the second factor by not combining a rural area with part of a large urban center. Since District Four does not combine a rural area with a large urban center, it satisfies the second factor and passes the tax approach.

District Five houses Alabama’s largest city, Huntsville, known for its unique government contract industry that supports NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center.159About Marshall, Nat’l Aeronautics & Space Admin., https://perma.cc/YCQ2-SH3K. However, Huntsville’s 2020 Census population of 215,006 only covers roughly a third of the population needed for a congressional district.160QuickFacts: Huntsville City, Alabama, U.S. Census Bureau, https://perma.cc/M5CW-BSXQ (listing the 2020 Census figure under “Population, Census, April 1, 2020”). Huntsville is immediately surrounded by either large swaths of rural area or the significantly smaller town of Florence (2020 Census population of 40,184), located in Alabama’s northwestern corner.161QuickFacts: Florence City, Alabama, U.S. Census Bureau, https://perma.cc/JM23-5YDD (listing the 2020 Census figure under “Population, Census, April 1, 2020”). The Author ultimately decided to cover the Huntsville Metropolitan region (Madison and Limestone Counties) and the immediate rural counties to keep the Huntsville tax base most intact and contained in one district.162Huntsville, AL Metro Area, Census Rep., https://perma.cc/9KNL-B2X3. However, District Five could include Limestone and Madison Counties and then span west to cover the intermediate rural area and Florence, which would include Lauderdale, Colbert, and Lawrence Counties. In this instance, a court would defer to the redistricting body so long as it kept Madison and Limestone Counties together as one coherent tax base.

Districts Six and Seven split the remaining area. District Six covers the northwest corner of Alabama, centered on Florence, and sweeps east to cover the rural area between Huntsville and Birmingham. District Seven covers Tuscaloosa County (home to the University of Alabama) and covers the southern exurbs of Birmingham before capturing the remaining rural counties north of District Four. Both districts cover large rural areas but keep Florence, a small population center on the border of Lauderdale and Colbert Counties, and Tuscaloosa County, which has a 2020 Census population of 227,036, intact.163QuickFacts: Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, U.S. Census Bureau, https://perma.cc/YV9A-MZQE (listing the 2020 Census figure under “Population, Census, April 1, 2020”). The state legislature and the special master split Tuscaloosa County to connect the Black Belt with Birmingham, which only further marginalized the rural interests of the Black Belt.164See infra Figures 1, 2 & 3 (showing that Livingston County Plan Three, the original congressional map, and the special master’s Remedial Plan Three all split Tuscaloosa County). Under this proposed shape of District Seven, however, the Tuscaloosa tax base remains intact. At the same time, the rural regions in the eastern part of the district are sufficiently populous to provide adequate incentive for a representative to consider their interests. However, so long as the Tuscaloosa and Florence tax bases remain intact, most other district configurations to cover the remaining area will likely satisfy the tax approach.

Ultimately, this configuration of Alabama’s congressional districts does not represent the only possible map that satisfies the tax approach but still reflects the considerations needed for a court to evaluate a Section Two or Fourteenth Amendment claim using the tax approach. Most importantly, the map generally keeps taxpayers benefitting from the same or similar tax-funded institutions and areas with similar tax revenue sources (industries) intact.

D. Weaknesses of the Tax Approach’s Alabama Congressional Districts

While this map is only one example of how Alabama’s congressional districts would look under the tax approach, the map is vulnerable to several criticisms. This Section addresses the three most potent criticisms.

First, the map contains five safe Republican seats, one lean-Republican seat, and one lean-Democratic seat. The strong Republican advantage results from the strong GOP performance in the 2022 Midterm Election, demonstrated by the following table.

| Tax Approach Alabama Map 2016–2020 Composite165 Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2020 Composite: Statistics, Dave’s Redistricting, https://perma.cc/94SU-XMX7. For the Partisan Advantage calculation, see supra note 11. The final column shows the shift from the 2020 Composite Partisan Advantage in this table to the 2022 Composite Partisan Advantage in the previous table. See Hooper Final Tax-Approach Map 2016–2022 Composite: Statistics, supra note 142. | |||

| District | Minority Population Percentage | Partisan Advantage

(|R – D|) |