Introduction

The state of Oklahoma harbors deep resentment toward Caleb Williams. As the highest-rated American football quarterback prospect of his class, Williams committed to the University of Oklahoma in July of 2020.1Parker Thune, At Long Last, Caleb Williams Commits to Oklahoma, Sports Illustrated: Okla. Sooners on SI (July 4, 2020, 9:09 PM), https://perma.cc/Mk32-Z288. Fans, coaches, and students instantly adored the 6’ 1” athlete. His big throwing arm, brilliant athleticism, and lightning-quick feet quickly reignited title hopes for an ever-proud collegiate football program eager to reclaim the national championship—one that had eluded it for two decades.2See Liam McKeone, NFL GM Comparing Caleb Williams to Prince Has Draft World Buzzing, Sports Illustrated (Apr. 23, 2024), https://perma.cc/EAL9-JRQJ; Chip Rouse, Oklahoma Football: Historically, OU Well Overdue for National Championship, Stormin’ in Norman (Aug. 23, 2023), https://perma.cc/Q7EM-6HHY.

Less than two years later, however, fans were bashing the college star on social media with an onslaught of threats, criticism, and ill-wishes.3John E. Hoover, How Long Until Oklahoma Fans Forgive Caleb Williams? There’s Precedent, but It Could Be a While, Sports Illustrated: Okla. Sooners on SI (Feb. 1, 2022, 1:12 PM), https://perma.cc/7TLT-NQ2P. Why the sudden resentment towards a player who made quite the splash as a freshman, subbing-in midway through a heated Texas-Oklahoma rivalry game in which he overcame a 21-point deficit to win 55-48?4Ryan Chapman, Caleb Williams Finally Announces Transfer to USC, Sports Illustrated: Okla. Sooners on SI, (Feb. 1, 2022, 11:58 AM), https://perma.cc/KTB5-6GTH. Curiously, it was not a mistake on the football field; Williams is reviled by the Oklahoma Sooner faithful because of what he did not do for their beloved team.

In 2022, two years after joining the team, Caleb Williams entered the transfer portal.5Chris Low, QB Caleb Williams Elects to Enter Transfer Portal but Will Keep Oklahoma Football an Option, ESPN: NCAAF (Jan. 3, 2022, 5:03 PM), https://perma.cc/A97Q-N5V3. His entry appeared to be an unserious scouting expedition; everyone, including Williams, knew that “Oklahoma was [still] at the top of the list.”6Grayson Weir, Caleb Williams Reveals How Oklahoma and Sooners Fans Pushed Him Away and Led Him to Transfer, brobible (July 15, 2022, 2:36 PM), https://perma.cc/U9ZT-YYFY. But a tumultuous period ensued: After Oklahoma lost their Heisman-maker coach, Lincoln Riley,7Riley coached three quarterbacks to a Heisman trophy—an award given to the best player in college football—in a span of six years: Baker Mayfield in 2017, Kyler Murray in 2018, and Caleb Williams in 2022. See Matt Wadleigh, The Story of Lincoln Riley’s 3 Heisman Trophy-Winning QBs, USA Today: Trojans Wire (Dec. 10, 2022, 8:28 PM), https://perma.cc/2YBY-Z7DK. A fifty percent Heisman rate is virtually unheard of for a coach, let alone a coach under forty years old. See id. to the University of Southern California (“USC”), the Sooner fans directed their frustration towards Williams as they grappled with both the departure of their coach and the humiliation of their star quarterback flirting with other teams in the portal.8Weir, supra note 6. Hysteria ensued, and Oklahoma quickly constructed a contingency plan, welcoming in a new transfer quarterback before Williams made a decision.9Id. Williams “resented how every step [the university took] was geared to force [him] into a hurried, emotional decision,” and his relationship with the fans and the coaches began to crumble.10Id. Less than a month later, the star quarterback made his move. Citing his goal to play in the NFL, Williams followed Riley to USC, leaving Sooner fans bitter and broken.11Id.

Williams’s transfer followed three recent, seismic changes in the college athletics landscape that made his move to USC possible and the opportunities in southern California more attractive. First, in April 2021, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (“NCAA”) proposed and ratified the “one-time opportunity” rule, allowing student-athletes who play baseball, football, basketball, and ice hockey to transfer schools once and play immediately; the association had previously required most athletes to sit out of competition the year after transferring as a method of deterrence.12Michelle Brutlag Hosick, DI Council Adopts New Transfer Legislation, NCAA (Apr. 15, 2021, 4:41 PM), https://perma.cc/E3NT-MHU8; Julia Elbaba, How NCAA Transfer Portal Works and What It Means for Players, NBC Sports Phila. (Dec. 8, 2022, 1:36 PM), https://perma.cc/94HC-2P7R. Second, just two months after the rule change, the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in NCAA v. Alston,13141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021). where a unanimous Court held that the NCAA’s education-related benefit restrictions on athletes violated the Sherman Act.14Id. at 2166. Finally, less than ten days after the ruling, the NCAA relinquished its century-long monopoly on the Name, Image, and Likeness (“NIL”) rights of college athletes, allowing players to make money off their personal brands through third-party NIL deals.15Michelle Brutlag Hosick, NCAA Adopts Interim Name, Image and Likeness Policy, NCAA (June 30, 2021, 4:20 PM), https://perma.cc/PV9T-4Y4E.

But those changes that allowed Williams to transfer and prosper in 2022—the biggest advances for athlete compensation in the last century—were trivial compared to the change that would soon follow. In 2024, the same year Williams was drafted to the NFL, the NCAA entered into a settlement with the Power Four conferences, for the first time instituting a revenue-sharing agreement that will see schools distributing up to 22% of their revenue to their student-athletes.16See Ranjan Jindal, Breaking Down the House v. NCAA Settlement and the Possible Future of Revenue Sharing in College Athletics, Chronicle (July 29, 2024), https://perma.cc/3YTX-Q6G8. The NCAA’s “Power Four” football conferences are: the Southeastern Conference (“SEC”), the Big Ten Conference, the Atlantic Coast Conference (“ACC”), and the Big 12 Conference. Bryan Kress, College Football Conference Realignments Explained: History, What To Know, Ticketmaster (Oct. 1, 2024), https://perma.cc/G575-55J3.

Written in short wake of the preliminary approval of the settlement, this Comment shows why the NCAA hurried to a deal: Noneducation-related benefit restrictions violate touchstone antitrust principles in the same way, and under the same law, as the education-related benefits restrictions struck down in Alston.17See Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2166–69 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). For decades, the NCAA has been a cartel that artificially suppresses student-athlete compensation. The justification for this suppression—consumer demand for “amateurism”—is a myth that is unsupported by any statistical data. When athlete compensation goes up, so does revenue.18See infra Section III.A. Thus, the noneducation-related compensation restrictions promulgated by the NCAA were also violations of the Sherman Act.19Sherman (Antitrust) Act, ch. 647, 26 Stat. 209 (1890) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. §§ 1–7). Recognizing this, the NCAA cut a deal on its own terms before being forced to accept a court’s terms.20See Jindal, supra note 16. But the 2024 settlement does not resolve these problems. Instead, it sets another arbitrary price cap on student-athlete compensation—one that continues to violate the Sherman Act and deprive student-athletes of the free market. In short: Athletes can, and should, do better.

This Comment proceeds in five parts. Part I outlines the NCAA and the rise of amateurism, detailing the history of the association and amateurism ideology. Part II explores NCAA v. Alston, the Supreme Court’s analysis of education-related benefits under the rule of reason, and the subsequent NIL legalization by the NCAA. Part III demonstrates why the NCAA’s noneducation-related benefit restrictions also violate the rule of reason. Part IV outlines the 2024 settlement and shows why it insufficiently protects the interests of the student-athletes. Finally, Part V outlines a potential framework post-settlement, considering system realities both with and without federal legislation.

I. The NCAA and the Rise of Amateurism

The NCAA has grown far from its twentieth century roots; today, the association is almost unrecognizable. The association was created with outside facilitation from President Theodore Roosevelt, who was concerned about an unchecked athletic system.21John Sayle Watterson, College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy 68–70 (2000). Roosevelt and other NCAA founders wished to restructure collegiate athletics and ensure that universities were carrying out the rules of play “in letter and spirit.”22Id. at 69. The association originally drafted its constitution in 1906, establishing the rules and regulations it sought to enforce for the next century.23See Palmer E. Pierce, The International Athletic Association of the United States: Its Origin, Growth and Function, in Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States 27, 29 (1907). The Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States became the NCAA in 1910. History, NCAA, https://perma.cc/986N-KCMU. One of those regulations is particularly pertinent:

No student shall represent a college or university in any intercollegiate game or contest who is paid or receives, directly or indirectly, any money, or financial concession, or emolument as past or present compensation for, or as prior consideration or inducement to play in, or enter any athletic contest, whether the said remuneration be received from, or paid by, or at the instance of any organization, committee or faculty of such college or university, or any individual whatever.24NCAA, Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Convention of the National Collegiate Athletic Association app. at 72 (1912) (establishing the eligibility rules at Article VII of the new NCAA by-laws). The appendix to the Seventh Annual Convention established the new NCAA Constitution and by-laws. Id. at 66–74.

This was the NCAA’s first stab at a philosophy that would deprive student-athletes of the fruits of their labor for the next century: It outlined the NCAA’s concept of amateurism—a founding principle grounded in the idea that collegiate athletes should not profit from their labor because they are not professionals.25Jack Falla, NCAA: The Voice of College Sports, A Diamond Anniversary History 1906–1981, at 25 (1981).

Unsurprisingly, the NCAA initially had trouble enforcing its amateurism policy. In 1919, a spokesperson for the NCAA stated the association “does not attempt to govern, but accomplishes its purposes by educational means, leaving to the affiliated local conferences the responsibilities and initiative in matters of direct control.”26Id. at 57. But the suggestion that the individual conferences were efficiently policing their member-institutions in 1919—when there were already 170 universities and a student body population of about 400,000—was a farce.27Id. In 1926, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching funded and conducted a study, visiting more than one hundred universities around the nation and conducting interviews with faculty, alumni, athletes, coaches, and others.28Ronald A. Smith, Pay for Play: A History of Big-Time College Athletic Reform 60, 69 (Benjamin G. Rader & Randy Roberts eds., 2011). The Foundation found that over 70% of the schools were subsidizing their athletes in some way—whether it was through jobs, loans, scholarships, or other miscellaneous funding.29Howard J. Savage, Harold W. Bentley, John T. McGovern & Dean F. Smiley, The Carnegie Found. for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number Twenty-Three: American College Athletics 241 (1929). Under the “honor system” as it then existed, the athletic space was ripe for cheating. As writer Paul Gallico observed in 1937, “If we have any conception of the real meaning of the word ‘amateur,’ we never let it disturb us. We ask only one thing of an amateur and that is that he doesn’t let us catch him taking the dough.”30Joseph N. Crowley, In the Arena: The NCAA’s First Century 68 (Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n et al. eds., 2006).

Though the not-so-discrete payments to athletes lasted for forty years, the NCAA finally established a mechanism to hold schools accountable if they would not comply with its amateurism policy.31Id. at 69. In 1948, the association adopted what it called the “Sanity Code.”32Id. Passed by a near-unanimous vote by all member-institutions, the Sanity Code allowed the association to completely expel a school that violated the NCAA constitution, including the amateurism policy.33Id. If two-thirds of the university membership voted to remove a fellow member, that school would be kicked out of the NCAA, lose the best scheduling opportunities, and experience a decrease in revenue.34See Smith, supra note 28, at 91. In other words, the NCAA’s amateurism policy finally had teeth.

But the Sanity Code was a trojan horse. Although the Code gave the NCAA more power to enforce its amateurism policy, the provision also quietly codified the NCAA’s approval of athletic scholarships.35Id. at 96. While the initial Sanity Code limited those scholarships to students demonstrating fiscal need, the Code provided member-institutions an initial taste of what athletic scholarships could do for program recruitment.36Id. Unsurprisingly, it did not take long for schools to boycott the “fiscal need” restriction.37Howard P. Chudacoff, Changing the Playbook: How Power, Profit, and Politics Transformed College Sports 10 (Randy Roberts et al. eds., 2015). “A coalition of southern schools, who favored no or watered down restrictions on scholarships, were joined by a few eastern schools, who believed that purging the Sanity Code was the only way to keep the NCAA from dissolving.”38Id. at 11. By 1956, the Code was replaced with a new rule: Athletes could be provided scholarships, up to the cost of attendance, simply for their athletic prowess.39Id. at 19. Thus the NCAA, which had championed amateurism since its inception, now flatly authorized schools to “pay” athletes hundreds of thousands of dollars.40Seeid. (listing categories of student-athlete expenses authorized for subsidization, in addition to the “full ride” scholarship).

The hypocrisy continued in 1973 when the association determined that some student-athletes were more amateur than others, and divided its member-institutions into three divisions: Division I, Division II, and Division III.41Crowley,supra note 30, at 89. Division I was to consist of teams “that [were] truly operating big-time programs and which approach[ed] intercollegiate athletics in a semi-professional or outright professional fashion.”42James V. Koch, A Troubled Cartel: The NCAA, 38 L. & Contemp. Probs. 135, 147 (1973). Those schools—and those who just missed the cut in Division II—were allowed to provide scholarships to their athletes.43Id. at 146–47. The remaining schools, who funneled themselves into Division III, would treat athletes as amateurs because of their “more modest goals and expectations.”44Id. at 137. This decision was, in both name and practice, the official split between compensated athletes (Divisions I and II) and non-compensated athletes (amateurs in Division III).

Despite the hypocrisy after the division split, the NCAA more effectively enforced its amateurism rules under the modified regime; its treatment of Reggie Bush is an example of its newly clenched iron fist.45Nicholas Reimann, Reggie Bush Won’t Get Heisman Back After NCAA Ruling, Forbes (July 28, 2021, 3:44 PM), https://perma.cc/6TBD-TE63. Bush, a legendary USC football player, won the Heisman trophy in 2005.46Id. Yet the NCAA forced him to give up the award in 2010 “amid an investigation into around $300,000 he received in cash and gifts during his collegiate playing days.”47Id. The NCAA hammered Bush and USC for engaging in a so-called “pay-for-play” agreement, forced the program to (retroactively) forfeit every game it won over the course of the 2005 season, and scrapped Bush’s (excellent) statistics from the record books.48Id. The association also banned him from the stadium for ten years.49Id. Though harsh, the NCAA’s punishment of Bush and USC demonstrates its commanding police power at the century’s turn.

But Williams, who played at USC just fifteen years after Bush did—and made far more money—did not suffer the same consequences. Shortly after the NCAA changed its transfer policy in 2021, the association legalized third-party NIL deals for all college athletes.50Hosick, supra note 15. Williams subsequently signed deals with Wendy’s, Beats by Dre, United Airlines, PlayStation, Dr. Pepper, and AT&T.51Caleb Williams – NIL Deals, On3, https://perma.cc/474Y-NS2Z. In the 2023 season, he sported an NIL valuation of over $2.5 million.52Caleb Williams – NIL Profile, On3, https://perma.cc/JDA9-Q8T6. And unlike Bush, he got to keep his Heisman trophy.

II. NCAA v. Alston and the Subsequent NIL Legalization

In 2021, while Caleb Williams was still suiting up for Oklahoma, the college athletic landscape underwent dramatic change. After the Supreme Court declared that restrictions on education-related benefits were an unlawful violation of the Sherman Act, the NCAA adopted a new NIL policy, allowing athletes for the first time to legally sign brand deals and profit from their own image and likenesses.

A. The Alston Litigation

The same year the NCAA created the new transfer rule, the Supreme Court crippled amateurism in Alston, concluding that the NCAA’s restriction of education-related benefits—such as tutoring payments and graduate scholarships for student-athletes—violated the Sherman Act.53NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2166 (2021). Justice Gorsuch, writing for a unanimous Court, opined that just because “some restraints are necessary to create or maintain a league sport does not mean all ‘aspects of elaborate interleague cooperation are.’”54Id. at 2156 (quoting Am. Needle, Inc. v. NFL, 560 U.S. 183, 199 n.7 (2010)). And though the opinion was strictly limited to education-related benefits on appeal, a scathing concurring opinion from Justice Kavanaugh suggested that a challenge to noneducation-related benefits should follow.55Id. at 2166–69 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).

Alston was filed in the Northern District of California by several disgruntled current and former collegiate student-athletes who played football and basketball.56See In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1061 (N.D. Cal. 2019), aff’d sub nom. Alston v. NCAA, 958 F.3d 1239 (9th Cir. 2020), aff’d, 141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021). The district court was tasked with applying established antitrust law to college sports—an enterprise unique enough to give any judge pause. Though horizontal price-fixing agreements—like the ones the NCAA promulgates—“are ordinarily condemned as a matter of law under an ‘illegal per se’ approach because the probability that [the] practices are anticompetitive is so high,” the district court used an antitrust test called the rule of reason because in collegiate sports, a “‘certain degree of cooperation’ is necessary.”57Id. at 1092 (internal quotation marks omitted) (first quoting NCAA v. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of Okla., 468 U.S. 85, 100 (1984); and then quoting O’Bannon v. NCAA, 802 F.3d 1049, 1069 (9th Cir. 2015) (quoting Bd. of Regents, 468 U.S. at 117)). The rule of reason is apt for analyzing fact-intensive unique cases in antitrust law to determine whether an unreasonable restraint on competition exists.58Id. at 1096.

The Court articulated the standard set by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in analyzing these special antitrust claims under the rule of reason test:

“Under the rule of reason burden-shifting scheme, plaintiffs first must ‘delineate a relevant market and show that the defendant plays enough of a role in that market to impair competition significantly.’” Second, if the plaintiffs make that showing, the burden then shifts to the defendants to offer evidence that a legitimate procompetitive effect is produced by the challenged behavior. Third, if the defendants do so, the burden then shifts back to the plaintiffs to demonstrate that there are less restrictive alternatives to the challenged conduct. Finally, if the plaintiffs fail “to meet their burden of advancing viable less restrictive alternatives,” the court then will “reach the balancing stage,” wherein the court “must balance the harms and benefits” of the challenged conduct to determine whether it is “reasonable.”59Id. (citations omitted) (quoting Cnty. of Tuolumne v. Sonora Cmty. Hosp., 236 F.3d 1148, 1150, 1160 (9th Cir. 2001)).

To simplify: First, the plaintiff must prove the defendant is restricting competition. Second, the defendant must demonstrate the restraints have a procompetitive effect in the field. And third, the plaintiff must establish the defendant could use less restrictive alternatives.60See id.

The district court did not address noneducation-related benefits, which would have included direct revenue sharing for collegiate athletes.61Id. at 1107. However, after narrowing the scope of its analysis to education-related benefits, the court concluded the plaintiffs prevailed on all aspects.62In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap, 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1110. First, the plaintiffs produced sufficient evidence that there were no viable substitutes for Division I basketball and FBS football, establishing that the NCAA had monopsony power.63Id. at 1097–98. Second, the court rejected the NCAA’s arguments that limiting education-related benefits promoted (1) amateurism, which it argued “enhances consumer demand for Division I basketball and FBS football,” and (2) the integration of athletes into their respective academic communities.64Id. at 1098. The court found there was no correlation between paying athletes more and a decrease in consumer demand, and that many education-related restrictions such as “those that limit tutoring, graduate school tuition, and paid internships, ha[d] not been shown to have an effect on enhancing consumer demand for college sports as a distinct product, because th[ose] limits [we]re not necessary to prevent unlimited cash compensation unrelated to education.” Id. at 1102. With regard to integration, the NCAA argued that allowing athletes to be rewarded with additional education-related benefits would drive a wedge between student-athletes and nonathletes. Id. But the court concluded there was no evidence that increasing compensation had resulted in increased separation between student-athletes and other students, and thus its procompetitive justifications were insufficient. Id. at 1103. Finally, the plaintiffs demonstrated that removing restrictions on education-related benefits would be virtually as effective in preserving amateurism and integration, since it would not result in unlimited cash payments, add compliance burdens on the NCAA, or disrupt consumer demand.65Id. at 1104–05.

The court relied on several key facts to support its decision. Contrary to the NCAA’s contentions, athlete compensation had increased in recent years despite policies that limited cash awards to the cost of attendance.66Id. at 1106. For example, the NCAA allowed athletes to earn more money through certain achievements: qualifying for a football bowl game; winning an award through the Student Assistance Fund or Academic Enhancement Fund (both of which assist student-athletes with financial needs and welfare); receiving per diem payments for travelling student-athletes; and obtaining post-eligibility graduate school scholarships.67Id. at 1072–74.

And when compensation increased, so did consumer demand. The plaintiffs pointed to an experiment conducted before and after an increase to the athletic scholarship limit, from 2014 to 2015.68In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap, 375 F. Supp. 3d at 1076. Following the increase in compensation, “revenues of the schools in the Power Five alone for basketball and FBS football increased from a very large amount in 2014-2015 disclosed under seal, to an even larger amount in 2015-16.”69Id. at 1076–77. The “Power Five” included the Pac-12, which is no longer considered a power conference. Kelsey Dallas, Will the Pac-12 Become a “Power” Conference Again? Here’s What Fans Think, YahooSports (Sept. 12, 2024), https://perma.cc/95ZP-HHR9. Thus the “Power Four” remain. Id.

So too at the University of Nebraska, which had created a program allowing for up to $7,500 in aid to be distributed to different athletes for education-related endeavors like graduate school.70Id. at 1077. The court found there was “no evidence that the creation of this program has reduced consumer demand for Nebraska sports or Division I basketball or FBS football in general”—in fact, rather than conceal the program from boosters, the athletic director advertised it at every opportunity available.71Id. at 1078.

On appeal from a disgruntled NCAA, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit affirmed.72Alston v. NCAA, 958 F.3d 1239, 1266 (9th Cir. 2020), aff’d, 141 S. Ct. 2141 (2021). While the NCAA did not challenge that the student-athletes proved the first prong of the test (NCAA rules have significant anticompetitive effects), it did take issue with the second and third prongs. See id. at 1257–62. The association re-argued that “[t]he challenged rules preserve ‘amateurism,’ which, in turn, ‘widen[s] consumer choice’ by maintaining a distinction between college and professional sports.” Id. at 1257 (second alteration in original). But the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit found the evidence considered by the district court persuasive: Loosening restrictions on education-related benefits would not adversely affect consumer demand, diminish viewership, or interfere with game attendance. Id. at 1257–62. The appellate judges agreed that the “district court struck the right balance in crafting a remedy that prevent[ed] anticompetitive harm to Student-Athletes while . . . preserving the popularity of college sports”73Id. at 1263. Notably, the court also rejected the NCAA’s vague definition of amateurism as a justification for restricting competition, admonishing the association for amateurism’s ever-changing nature.74Id. at 1258. Amateurism was not “immortalize[d] . . . as a matter of law,” but rather “a ‘nebulous concept prone to ever-changing definition.’”75Id. at 1258–59 (citing O’Bannon v. NCAA, 802 F.3d 1049, 1083 (9th Cir. 2015) (Thomas, C.J., concurring in part and dissenting in part)). So, the court held, consumer surveys—meant to show that fans associated amateurism with college sports—were “of limited evidentiary value”; the respondents could hardly have known what “amateurism” meant.76Id.

The NCAA appealed again to the Supreme Court, which noted the case’s uniqueness.77NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2154–55 (2021). Unlike most antitrust cases, the litigants here were more amicable.78Id. No party disagreed that the NCAA had a monopoly on the collegiate athletic market.79Id. No party disagreed that these restrictions decrease the compensation that Division I athletes would earn at a fair competitive market price.80See id. All parties agreed that the NCAA “may permissibly seek to justify its restraints” by citing “procompetitive effects . . . in the consumer market.”81Id. at 2155. Instead, the Court was faced with two issues on appeal.82Id. at 2155, 2160.

The first issue was whether the rule of reason applied.83Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2155. The NCAA argued for an “abbreviated deferential review,” typically used when there are “restraints at opposite ends of the competitive spectrum” that allow a court to quickly uphold anticompetitive conduct.84Id. One side of the spectrum exists where restraints are so incapable of harming competition that it would be impossible to have a competent antitrust claim—such as a joint venture that “command[ed] between 5.1 and 6% of the relevant market.” Id. at 2156 (alteration in original). On the other end of the spectrum, there are some restraints which so clearly harm competition they may be rejected as unlawful after a “quick look.” Id.; see Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 692–93 (1978) (characterizing the agreement as “an absolute ban on competitive bidding” and thus harmed competition as to be immediately unlawful). But the Court disagreed, holding the NCAA’s “myriad rules and restrictions” warranted a more sophisticated review because of the complicated market.85Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2156. The Court echoed the district court’s reasoning, holding that the rule of reason is uniquely situated for analyzing fact-intensive antitrust relationships; since the market realities of the intercollegiate space had changed significantly since the Supreme Court last analyzed the industry (1984),86The Court found in NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma:

The NCAA plays a critical role in the maintenance of a revered tradition of amateurism in college sports. There can be no question but that it needs ample latitude to play that role, or that the preservation of the student-athlete in higher education adds richness and diversity to intercollegiate athletics and is entirely consistent with the goals of the Sherman Act.

468 U.S. 85, 120 (1984). The NCAA argued in Alston that this quote foreclosed a rule of reason analysis. Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2157. another look was overdue.87Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2158.

Post-1984, the NCAA continued allowing conferences to raise limits on athletic scholarships and permitted other funds for the athletes, contributing to market shifts.88See supra Part I. Further, “In 1985, Division I football and basketball raised approximately $922 million and $41 million respectively. By 2016, NCAA Division I schools raised more than $13.5 billion.”89Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2158 (citation omitted). The Court found that a new analysis—under the rule of reason—was not only appropriate, but necessary.90See id. at 2157 (finding “[this] dispute presents complex questions requiring more than a blink to answer”).

The second issue on appeal concerned the district court’s application of the rule of reason analysis.91Id. at 2160. Beginning with the first prong—in which the plaintiffs had to prove the defendant was restricting competition—the Court declared the athletes had passed their burden with flying colors, an unusual feat under a rule of reason analysis.92Id. at 2160–61. The Court noted plaintiffs rarely pass the first step in a rule of reason analysis: Since 1977, U.S. courts have decided the plaintiff failed to meet its burden under step one of the test in ninety percent (809 of 897) of rule of reason cases. Id. at 2161. “[B]ased on a voluminous record,” the athletes demonstrated that the NCAA was artificially suppressing wages and impairing their opportunity to compete.93Id. at 2161. Next, under the second prong, the Court again agreed with the district court that the NCAA’s amateurism rationale had no basis in fact—the NCAA failed entirely “to establish that the challenged compensation rules . . . ha[d] any direct connection to consumer demand.”94Id. at 2162 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 375 F. Supp. 3d 1058, 1070 (N.D. Cal. 2019)).

The Court’s conclusion under the first and second prongs made its decision under the third prong (where the plaintiffs must demonstrate the defendant could employ a less restrictive alternative) a mere formality: A “legitimate objective that is not promoted by the challenged restraint can be equally served by simply abandoning the restraint, which is surely a less restrictive alternative.”95Alston, 141 S. Ct. at 2162 (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting 7 Phillip E. Areeda & Herbert Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law: An Analysis of Antitrust Principles and Their Application ¶ 1505, at 428 (4th ed. 2017)). The evidence showed that restrictions on education-related benefits did not promote competition, and thus the restrictions could simply be abandoned to cure the rule of reason violation.96See id.

Justice Kavanaugh delivered a blistering concurrence, pointing out the circular hypocrisy in defining collegiate athletes as amateurs and then refusing to pay them based on the definition the NCAA wrote: “Nowhere else in America can businesses get away with agreeing not to pay their workers a fair market rate on the theory that their product is defined by not paying their workers a fair market rate.”97Id. at 2169 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). Kavanaugh confirmed that the NCAA’s business model would be illegal in almost every industry in the U.S.—for example, “[a]ll of the restaurants in a region cannot come together to cut cooks’ wages on the theory that ‘customers prefer’ to eat food from low-paid cooks.”98Id. at 2167.

Most importantly for the purposes of this Comment, Justice Kavanaugh acknowledged that Alston sets the standard for analyzing the NCAA’s remaining compensation restrictions, including restrictions on revenue sharing with athletes; the Court uniformly held the NCAA is not exempt from antitrust laws, and thus the remaining restrictions fall under rule of reason scrutiny.99Id. Further, not only did Justice Kavanaugh confirm the remaining compensation restrictions would be analyzed under the rule of reason, he asserted that they should be analyzed under the rule of reason, and that if they were, they would likely be declared in violation of the Sherman Act:

The bottom line is that the NCAA and its member colleges are suppressing the pay of student athletes who collectively generate billions of dollars in revenues for colleges every year. Those enormous sums of money flow to seemingly everyone except the student athletes. College presidents, athletic directors, coaches, conference commissioners, and NCAA executives take in six- and seven-figure salaries. Colleges build lavish new facilities. But the student athletes who generate the revenues, many of whom are African American and from lower-income backgrounds, end up with little or nothing.100Id. at 2168.

B. The Impact of Alston on the NCAA: NIL Legalization

Less than ten days after the conclusion of Alston, and possibly seeing the writing on the wall, the NCAA took one step back to avoid getting bulldozed. The association released a statement, confirming that it would officially allow collegiate athletes to sign brand deals selling their names, images, and likenesses.101Hosick, supra note 15. Now, athletes could be paid for promoting different products or businesses—or, more commonly, school boosters could indirectly pay athletes through NIL collectives to convince them to play for the boosters’ favorite programs.102SeeDennis Dodd, NCAA Aims to Crack Down on Boosters Disguising ‘Pay for Play’ as Name, Image and Likeness Payments, CBS Sports (May 3, 2022, 10:14 PM), https://perma.cc/HS7E-TRWH. NIL legalization was a decisive blow for amateurism ideology—already on its last legs after Alston—which put millions of dollars on the table for student-athletes around the country.

Though NIL money could not come directly from the schools, institutions created specific departments to facilitate those commercial relationships, and thus the NIL legalization became a recruiting tool.103Id. For example, on January 24, 2022, Ohio State University released a recruiting statement based on NIL policy:

A total of 220 student-athletes have engaged in 608 reported NIL activities with a total compensation value of $2.98 million. All three figures rank No. 1 nationally, according to Opendorse, the cutting edge services company hired by Ohio State to help its student-athletes with education and resource opportunities to maximize their NIL earning potential. . . . [Additionally,] [t]his week Ohio State student-athletes will learn of a strategic new resource – the NIL Edge Team – developed by the Department of Athletics that will help create and foster best-in-class NIL opportunities for them.104Dept. of Athletics Creates NIL Edge Team, Updates Guidelines, Ohio St. (Jan. 24, 2022, 10:55 AM), https://perma.cc/FA6A-8FAE.

As athletes like Caleb Williams were making millions of dollars per year through NIL, the cracks in the inconsistent amateurism ideology were widening. But something was still missing. The NIL payments allowed for athletes to be paid indirectly, either through booster NIL collectives or independent marketing agreements, but the restriction on revenue sharing from the schools remained; even though athletes were being paid from independent sources, the schools were still keeping the direct revenue for themselves.105See John T. Holden, Marc Edelman & Michael A. McCann, A Short Treatise on College-Athlete Name, Image, and Likeness Rights: How America Regulates College Sports’ New Economic Frontier, 57 Ga. L. Rev. 1, 32–33, 36, 75 (2022). Part III explains why that unjust enrichment is impermissible under the rule of reason and the Sherman Act: A wrongdoer is not absolved from liability just because the victim happens to be compensated by a third party.

III. NCAA Restrictions on Noneducation-Related Benefits Fail Under a Rule of Reason Analysis

In Alston, the Supreme Court laid the framework for how the NCAA’s noneducation-related benefits should be analyzed going forward. Justice Kavanaugh said it best: “After today’s decision, the NCAA’s remaining compensation rules should receive ordinary ‘rule of reason’ scrutiny under the antitrust laws. . . . And the Court stresses that the NCAA is not . . . entitled to an exemption from [them].”106NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2167 (2021) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). His interpretation comports with the majority, which discussed the NCAA’s monopsony power in its entirety in the introductory section of Alston, before narrowing the analysis to one concerning education-related benefits.107See id. at 2148–55. In the Court’s view, not only did the NCAA accept that its members collectively enjoy monopsony power and that the student-athletes had nowhere else to sell their labor, but the association acknowledged that monopsony is the only reason its business model works.108See id. at 2156.

One need not deliberate on the topic to realize the Court is correct. The NCAA is a cartel—that is, an organization of firms that make an agreement to control market prices. The NCAA:

(a) sets the maximum price that can be paid for intercollegiate athletes; (b) regulates the quantity of athletes that can be purchased in a given time period; (c) regulates the duration and intensity of usage of those athletes; (d) occasionally fixes the price at which sports outputs can be sold (for example, the setting of ticket prices at NCAA championship events which are held on the campuses of cartel members); (e) periodically informs cartel members about transactions, costs, market conditions, and sales techniques; (f) occasionally pools and distributes portions of the cartel’s profits, particularly those which result from intercollegiate football and basketball; and (g) polices the behavior of the members of the cartel and levies penalties against those members who are deemed to be in violation of cartel rules and regulations.109Koch,supra note 42, at 136–37 (footnote omitted).

Absent a special situation, this type of restriction is per se unlawful under the Sherman Act and the first prong of the rule of reason.110See 15 U.S.C.A. § 1 (West, Westlaw through P.L. 118-78). The first prong of the rule of reason requires the plaintiff to prove the defendant is restricting competition. See supra text accompanying notes 59–60. Thus, when the NCAA attempts to justify its restrictions based upon consumer demand, it submits itself to the more complex rule of reason analysis.111NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2167 (2021) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). “The NCAA is free to argue that, ‘because of the special characteristics of [its] particular industry,’ it should be exempt from the usual operation of the antitrust laws—but that appeal is ‘properly addressed to Congress.’”112Id. at 2160 (majority opinion) (alteration in original) (quoting Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 689 (1978)).

The NCAA is left to argue the second prong: that its noneducation-related restrictions benefit competition and consumer demand. Section III.A shows, through historical examples and real data, that increased compensation fails to correlate with a fall in consumer demand. Section III.B then argues that even if a correlation exists between compensation restrictions and consumer demand, and the consumer was receiving some kind of amorphous benefit, the anticompetitive effects of amateurism far outweigh those benefits.

A. Increased Compensation Does Not Correlate with a Fall in Consumer Demand

Were the NCAA’s noneducation-related benefit restrictions to be challenged, the NCAA would have to prove there are procompetitive effects for its noneducation-related compensation restrictions under the second prong of the rule of reason113Id. at 2167 (Kavanaugh, J., concurring).—an affirmative burden it cannot meet. As discussed in Part I, supra, as athletic compensation has increased in recent years, consumer demand has risen.114See supra Part I. And several studies have concluded with no evidence of a correlation between amateurism policy and a decline in consumer demand.115See supra Section II.A.

This Section identifies five further examples that show the “amateurism promotes competition and revenue” argument is, and always has been, a myth: (1) in the half-century before amateurism was enforced, viewership exploded; (2) recent restrictions on coach salaries had no effect on competition or revenue; (3) payment of Olympic athletes after a long period of amateurism increased viewership; (4) “free agency” in American professional baseball increased revenue and profit; and (5) the recent NIL legalization correlates with schools making more money than ever before.

First, if increases in compensation statistically decrease viewership numbers, then the years 1900–1950 must have all been annual miracles. At the time of the Carnegie study in 1926,116See supra Part I. collegiate coaches were routinely making the same amount of money as a top-level professor at their respective schools.117Smith, supra note 28, at 65–66. And, as discussed in Part I, supra, the schools could not supervise or monitor the not-so-surreptitious payment of athletes.118See supra Part I. Thus, coaches at schools that wanted to compete for athletes would often tempt them with whatever they could: money, benefits, cars, sex, and anything else at their disposal.119See Crowley,supra note 30, at 66, 68. But this insurrection against amateurism did not quell fan viewership; in fact, the first half of the twentieth century saw unprecedented growth in the space.120Smith, supra note 28, at 59. By 1930, seventy-four massive 60,000 seat college football stadiums were erected across the country to fulfill consumer demand—and the stadiums only got bigger and more prevalent.121Id. at 64. In October 1922, the very first college football game aired on radio.122Crowley, supra note 30, at 61. Subsequently, “Overall radio sales grew at a staggering rate during the decade, from $60 million in 1922 to more than $842.5 million in 1929, an increase of 1,300 percent.”123Id. The first half of the twentieth century is a perfect case study on the consequences of uncapped NCAA compensation—athletic viewership booms.

Second, the NCAA’s compensation restrictions have previously failed antitrust scrutiny.124See Law v. NCAA, 134 F.3d 1010, 1024 (10th Cir. 1998). In 1998, in Law v. NCAA,125134 F.3d 1010 (10th Cir. 1998). the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit evaluated a NCAA wage restraint on assistant coaches.126Id. at 1015. To justify this policy, the NCAA argued that its salary cap would “help to maintain competitive equity by preventing wealthier schools from placing a more experienced, higher-priced coach in the position of restricted-earnings coach.”127Id. at 1024. Disagreeing, the court struck down the policy and noted that the NCAA failed to prove that salary restrictions “enhance[d] competition, level[ed] an uneven playing field, or reduc[ed] coaching inequities.”128Id. Thus, even twenty years before Alson, the NCAA was asserting conclusive statements about promoting competitive equity in the absence of any concrete evidence.

Third, after the International Olympic Committee ended Olympic amateurism and began allowing athlete compensation, viewership skyrocketed. The Olympics, one of the most popular sporting events in the world, also cited amateurism as one of its founding tenants; from its inception until the late twentieth century, amateurism was actually enforced, and professional athletes were unable to compete.129Matthew P. Llewellyn & John Gleaves, The Rise and Fall of Olympic Amateurism 2 (Randy Roberts et al. eds., 2016). But in 1992, after a star-studded basketball tournament at the Barcelona Olympics,130Dubbed the “best basketball team ever assembled,” the 1992 U.S.A. Men’s basketball team had 11 future hall of famers, including Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson, and Larry Bird, and won all of its games by at least 30 points. Hall of Fame, U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum, https://perma.cc/4KB3-NPQA. the International Olympic Committee declared that the professionals—and the lucrative television deals that came along with their participation—would be permitted.131Llewellyn & Gleaves, supra note 129, at 187–88. Notwithstanding public opposition to letting professional athletes compete, “consumer interest in the Olympics remained high and revenues generated by the event continued to rise during the same period.”132Andy Schwarz & Kevin Trahan, The Mythology Playbook: Procompetitive Justifications for “Amateurism,” Biases and Heuristics, and “Believing What You Know Ain’t So”, 62 Antitrust Bull. 140, 152 (2017) (quoting O’Bannon v. NCAA, 7 F. Supp. 3d 955, 977 (N.D. Cal. 2014), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 802 F.3d 1049 (2015)). When questioned in federal district court litigation about amateurism in the Olympics, a Stanford economist highlighted the myth:

[Expert Witness] [Regarding an article written in the 1960s about amateurism]: This was the era when there was debate about whether professionals should be allowed to be in the Olympics. This article is written roughly 20 years before they were allowed. And it quotes an Olympic official as saying, if professionals are allowed into the Olympics, the Olympics would be dead in eight years.

[Plaintiffs’ Attorney:] Did that happen?

[Expert Witness:] No.133Transcript of Record at 227:25–228:11, O’Bannon, 7 F. Supp. 3d 955 (No. 4:09-cv-03329).

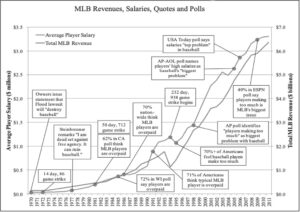

Fourth, “free agency” in baseball—a process that allows players to pick between whatever teams offer them a contract after their current deal expires—drastically increased revenue.134Schwarz & Trahan, supra note 132, at 149–50. Until the 1970s, baseball players could not participate in free agency.135See id. Baseball policymakers at the time thought that if players could go wherever they wanted at the expiration of their contracts, the game would be destroyed.136Id. at 149 & n.49. Joe Cronin, the president of the American League in 1970, said that if players were granted free agency, “professional baseball would simply cease to exist.”137Abraham Iqbal Khan, Curt Flood in the Media: Baseball, Race, and the Demise of the Activist Athlete 92–93 (2012) (citing Leonard Koppett, Flood’s Suit Could Cost Baseball $3 Million, Sporting News (Jan. 31, 1970), https://perma.cc/YUE7-UBNV). In reality—just two years later in 1972—free agency was lifted, and player compensation and revenue skyrocketed as reflected in Figure 1.138Schwarz & Trahan, supra note 132, at 149–50.

Figure 1139Id. at 150 (footnote omitted) (citing Expert Report of Daniel A. Rascher on Injunctive Class Certification at 78, In re NCAA Athletic Grant-in-Aid Cap Antitrust Litig., 311 F.R.D. 532 (N.D. Cal. 2016) (No. 4:14-md-02541)).

Finally, if a connection between amateurism and revenue existed, then revenue from college football should have decreased after NIL legalization. But in the 2022 fiscal year, Ohio State University—the top revenue generator in collegiate athletics—garnered roughly $251 million in earnings, eclipsing the 2020 university record of around $233 million.140Ohio State Athletics Reports Rebound in Revenue in 2022, Ohio St.: Dep’t of Athletics (Jan. 26, 2023), https://perma.cc/2QH4-7XLH. In fiscal year 2021 (July 1, 2020, to June 30, 2021), the university garnered just $106 million in revenue due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Id. This came the same year the university announced it had generated the most NIL money for its athletes:

A total of 220 student-athletes have engaged in 608 reported NIL activities with a total compensation value of $2.98 million. All three figures rank No. 1 nationally, according to Opendorse, the cutting edge services company hired by Ohio State to help its student-athletes with education and resource opportunities to maximize their NIL earning potential.141Dept. of Athletics Creates NIL Edge Team, supra note 104.

If amateurism was anything but a myth, consumers would have seen the almost $3 million generated in NIL money and ditched their college sports fandom. Instead, revenue went up. Ultimately, evidence suggests that “consumer demand for FBS football and Division I basketball-related products is not driven by the restrictions on student-athlete compensation but instead by other factors, such as school loyalty and geography.”142Schwarz & Trahan, supra note 132, at 142 (quoting O’Bannon v. NCAA, 7 F. Supp. 3d 955, 1001 (N.D. Cal. 2014), aff’d in part, rev’d in part, 802 F.3d 1049 (2015)).

B. The Anticompetitive Effects of Amateurism Far Outweigh Any Perceived “Competitive Benefits”

As proved, there is no factual basis behind the NCAA’s amateurism policy. The second and third prongs of the rule of reason, then, collapse into one: The NCAA cannot meet its burden under the second prong and thus “[consumer demand] that is not promoted by the [amateurism] restraint can be equally served by simply abandoning the restraint, which is surely a less restrictive alternative.”143NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2162 (2021) (internal quotation marks omitted) (quoting 7 Areeda & Hovenkamp, supra note 95, ¶ 1505, at 428). But even if the NCAA’s amateurism claims had merit, and there were no less restrictive alternatives proffered by the plaintiffs, the NCAA restriction is still unlawful because it fails under the unofficial “fourth” step of the rule of reason.144Ted Tatos, NCAA Amateurism as an Anticompetitive Tying Restraint, 64 Antitrust Bull. 387, 390 (2019). The fourth step is an implicit step that applies only if a Court finds the defendant met his burden under the second prong and the plaintiff fails in providing a less restrictive alternative under the third prong.145Id. at 390 & n.14. Under this unofficial step, a court is required to balance the anticompetitive effect of amateurism against any perceived consumer benefits.146Id.

Here, when balancing the amorphous concept of “consumer demand” against the anticompetitive effect on student-athletes, the student-athletes win in a blowout. Everyone but the athletes—the only irreplaceable group in the entire system—gets a piece of the extraordinarily lucrative pie.147See Matt Connolly, Big Ten, SEC Top $800 Million in Revenue as Power 5 Conferences Total More than $3.3 Billion in 2022, On3 (May 19, 2023), https://perma.cc/CJ9B-JH6N. In 2022, the teams comprising the Power Five conferences (the top five revenue producing conferences in the country) generated approximately $3.3 billion in revenue.148Id. In the same year, the NCAA’s former chief operating officer and president made over $6.8 million.149Daniel Libit & Eben Novy-Williams, NCAA Mints Millionaires as Revenue Rises and Workforce Shrinks, Sportico (May 24, 2023, 11:33 AM), https://perma.cc/K4U4-MLNM. And in 2023, Alabama football head coach Nick Saban alone made $11.4 million.150Amanda Christovich, Doug Greenberg & Rodney Reeves, Who Is Highest-Paid Coach in College Football?, Front Off. Sports (July 26, 2024, 10:36 AM), https://perma.cc/LA5Q-YQTA. To limit the college athletes to the cost of attendance, while the proponents and perpetrators of the system profit handsomely on the backs of their labor, is to sanction the very type of activity the Sherman Act was passed to prohibit.

The system is harmful in another way: Division I athletics require a full-time job level commitment, and students often leave college without a ticket to the professional leagues, possessing no marketable skills.151Neal Newman, Let’s Get Serious – The Clear Case for Compensating the Student Athlete – By the Numbers, 51 N.M. L. Rev. 37, 56 (2021). Most Division I players spend at least 40 hours per week practicing, in the weight room, or doing other team activities outside of school.152Jake Novak, The Ugly Truth About Major College Football, CNBC (Aug. 13, 2017, 2:00 PM), https://perma.cc/V8WR-6D2Q. “The fact of the matter is, the demands put on these ‘student-athletes’ are so great, so time intensive, and so consuming, that they have little, if any, opportunity to major in meaningful, substantive, marketable educational opportunities while they are engaged in their respective sport.”153Newman, supra note 151, at 56. Thus, the student-athletes, who dedicate the equivalent of a full-time job to their athletics, often leave school with a degree but—as former Purdue football player Albert Evans put it—it’s often “a piece of paper they don’t know how to use while surrounded by family and social structures that don’t know what to do with them either.”154Travis Miller, Here’s What a Former Purdue Football Player Wants You to Know About Being a Student Athlete, SB Nation:Hammer & Rails (Mar. 13, 2018, 12:07 PM), https://perma.cc/5ZXA-QAYD.

And the odds of being drafted, even at the Division I level within the best sports programs, is slim:

Based on NCAA statistics that compiled data for 2018, 73,557 young men were playing Division I college football; 16,346 of these players were eligible for the 2018 NFL Draft. Just 1.5% or 255 of those players were drafted that year. Honing those odds somewhat, roughly 73% of the players drafted in that 2018 draft came from the Power 5 Conferences. During that year, the Power 5 Conferences had 1,739 draft eligible players with 185 of those players being drafted (i.e. 11%).155Newman, supra note 151, at 58 (footnotes omitted).

The NCAA knows these statistics. The college institutions know these statistics. The athletic trainers know these statistics. The coaches know these statistics. But the athletes, first stepping foot on the college campus at eighteen, with the massive ego required to play sports at a high level, believe they can beat those odds. As a result, the athletes—who generate billions of dollars for their institutions—are more likely than not to leave college without a degree they can use and without payment from their university.

In short, the NCAA has not—and cannot—proffer any “consumer demand” justification for its amateurism policy. But even if it could, student-athletes have very low odds at going pro.156See supra Section III.B. The fact that athletes must dedicate 40 hours per week to sports can diminish the value of their education and the degree they graduate with—meaning that many of these athletes leave college with very little professional skill and without compensation from the university. Even if there were “consumer demand” benefits from amateurism, the objective reality of the collegiate sports industry far outweighs those benefits.

IV. The House Settlement

On May 23, 2024, under four months before Caleb Williams would play his first game in the NFL, the NCAA and the Power Five157The Power Five is now the Power Four after the dissolution of the Pac-12. Jim Biringer, Chip Kelly Can’t Believe Pac-12 Dissolved So Quickly, Full Press Coverage (Mar. 19, 2024), https://perma.cc/2WLU-YURV; seesupra note 69. entered into a settlement, attempting to resolve three lawsuits in federal court that had each challenged the NCAA’s compensation rules on antitrust grounds.158Joel Buckman, Steve Argeris & Evan Guimond, What the Proposed House Settlement Means for NCAA Division I Institutions, Hogan Lovells (June 27, 2024), https://perma.cc/3N58-5M3k. There are currently three relevant lawsuits. Complaint, House v. NCAA, No. 4:20-cv-03919 (N.D. Cal. filed June 15, 2020); Complaint, Carter v. NCAA, No. 4:23-cv-06325 (N.D. Cal. filed Dec. 7, 2023); Complaint, Hubbard v. NCAA, No. 4:23-cv-01593 (N.D. Cal. filed Apr. 4, 2023). Perhaps realizing that it could no longer justify its direct compensation restrictions under rule of reason scrutiny,159See supra Part III. the NCAA made an even more significant move away from its amateurism restraints. It was “late in the fourth quarter” for the NCAA, and it was losing badly. With every passing day it looked increasingly likely that a court would declare all NCAA restrictions on compensation unlawful under the Sherman Act.160See NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2166–67 (2021) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring. Under that pressure, the NCAA hurried to salvage a deal; better to settle on bad terms that it could control than to lose in court on terms that it could not.

But the settlement is insufficient to remedy the grievances addressed so far. At first glance, the settlement appears to fix many issues elucidated in this Comment. It pays around $2.78 billion in damages to a class of former athletes who were unable to compete in a fair market when they were participating in NCAA sports,161See Dan Murphy, Answering the 10 Biggest Questions About the NCAA Antitrust Settlement, ESPN: NCAAF (July 28, 2024, 9:00 AM), https://perma.cc/R66L-BBBU. The damages portion of the settlement will be paid out to athletes who played Division I sports from 2016 through 2024. Id. For several athletes, the damages award will be prorated based on that athlete’s potential earning power while in college, had the athlete played during the transfer portal and NIL era. See id. and establishes a long-awaited revenue-sharing agreement for the athletes.162Buckman et al., supra note 158. Still, upon closer inspection the revenue-sharing agreement is deficient. While it is a significant victory for the athletes in their battle against the NCAA, the agreement fails to produce a workable solution to the amateurism problem outlined in Parts I–III, supra. A cap on student-athlete revenue is an antitrust violation, whether the NCAA set the cap at zero dollars in the early twentieth century, or at millions of dollars in 2024. In short, the student-athletes should reject the settlement and pursue a better deal.

The settlement lays out a comprehensive scheme for distributing a portion of the generated athletic revenue to student-athletes. In essence, the schools have agreed to purchase the right to use each athlete’s NIL through contracts with the players; similar to the present-day NIL payments from boosters, the schools will now be permitted to pay the athletes directly. Schools will be able to give out around $23.1 million to student-athletes—distributed however they wish—in addition to the current methods of compensation such as NIL,163NIL deals are subject to some restrictions under the settlement likely meaning NIL compensation will be generally lower under the terms of the settlement. See infra text accompanying notes 168–72. athletic scholarships, and stipends.164Murphy, supra note 161. The $23.1 million figure is “based on a formula that gives athletes 22% of the money the average power conference school makes from media rights deals, ticket sales, and sponsorships.”165Id.

The revenue-sharing agreement in the settlement is modeled after major American professional sports leagues, where economists estimate that the athletes get about half the revenue their sport generates; the 22% revenue figure, combined with the scholarships, stipends, and other benefits given to student-athletes, is estimated to give athletes at Power Five schools “roughly half of what the athletic department makes on a yearly basis.”166Id. And similar to the NFL and other professional sports leagues with a “salary cap,” the $23.1 million cap will increase by 4% every year: An economist hired by the plaintiffs in House projects that “the cap [will] increase roughly $1 million each year, ending at $32.9 million per school by the 2034-35 academic year.”167Id.

However, while the settlement may appear reasonable, it is highly flawed. Most obviously, it sets another arbitrary cap on the free market. Think back to Alston and the rule of reason—the problem was not the value at which the NCAA capped pay-for-play when players could not legally receive percentages of revenue from the schools, but the arbitrary price-cap itself.168See NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2156–57 (2021). In the eyes of antitrust law, so long as the NCAA continues to couch its procompetitive justifications in amateurism hypocrisy, it cannot pass the rule of reason—no matter what price cap it sets.169See supra Part III. Whether the cap is $0 or $23.1 million, the NCAA is not letting the free market work.

The settlement also allows the NCAA to more effectively manage third-party NIL deals, giving it enforcement power to ensure that NIL deals are legitimate endorsement compensation, rather than faux pay-for-play agreements from boosters.170See Murphy, supra note 161. “Along with a clause that says booster payments to athletes must be for ‘a valid business purpose,’ the settlement also gives the NCAA power to create future rules to close any unforeseen loopholes ‘designed to defeat or circumvent’ the prohibition on booster payments.”171Id. Finally, the settlement prevents athletes who opt in from bringing any future claims against the NCAA for issues related to NIL compensation or any other conduct addressed in the lawsuit.172See Michael McCann, NCAA House Settlement Preliminarily Approved, Sportico (Oct. 7, 2024, 2:48 PM), https://perma.cc/J4L4-AUWP.

On first viewing, Judge Claudia Wilken of the Northern District of California—concerned with the restrictions on third-party NIL deals—called for all parties to go “back to the drawing board” and denied the settlement preliminary approval.173Justin Williams, House v. NCAA Settlement Granted Preliminary Approval, Bringing New Financial Model Closer, Athletic (Dec. 28, 2024), https://perma.cc/7J7R-6WJS. Subsequently, attorneys agreed to amend the “booster” language to permit the NCAA to only continue its existing prohibitions on “faux” NIL payments, not to add new ones.174Plaintiffs’ Supplemental Brief in Support of Motion for Preliminary Settlement Approval at 8–10, In reColl. Athlete NIL Litig., No. 4:20-cv-03919 (N.D. Cal. filed Sept. 26, 2024), ECF No. 450. The attorneys also added a check on NCAA power, allowing student-athletes or institutions to challenge any payment-related suppressions by the NCAA in front of a neutral arbitrator.175Id. at 2. On October 7, 2024, after reviewing the modifications, Judge Wilken granted the settlement preliminary approval, taking a huge step towards the settlement’s final confirmation.176Pete Nakos, Judge Preliminarily Approves House v. NCAA Settlement, On3 (Oct. 7, 2024), https://perma.cc/CRF2-ATHN. Barring any setbacks, when Judge Wilken grants final approval to the settlement in 2025, she will usher in a new landscape for collegiate athletics.177Id.

V. Into Overtime: What’s Next for College Sports?

This Comment has established that NCAA restrictions on student-athlete compensation are unlawful under the Sherman Act. It has also shown that the House settlement will deprive millions of athletes from a truly competitive athletic market. This Part offers commentary on the future of the athletic space, in a world where it remains both subject to House and unregulated by the federal government, or alternatively, in a world where Congress or an administrative agency elects to regulate the space. It then argues that uncapped revenue sharing is the way forward.

A. In the Absence of Regulation: Living with the House Settlement

When asked for comment after the initial agreement of the House settlement, plaintiffs’ attorney Jeffrey Kessler said that he was “very, very pleased” with the $2.8 billion settlement, which would be “fair and transformative for the athletes.”178Daniel Libit, Kessler Defends House v. NCAA Deal Amid Fontenot Case Flak, Sportico (May 22, 2024, 4:24 PM), https://perma.cc/BY4R-G42T. But athletes who feel the settlement is not so “fair” are not without remedy. Athletes who would be covered under the proposed House settlement can safely opt out of the settlement and pursue another deal—a decision that, if it picks up enough traction, could result in thousands of athletes initiating or joining new lawsuits. In that scenario, the NCAA—which hoped that House would end antitrust litigation against it—would have to continue to justify its regulations in court.179Eric Prisbell, Judge Rules Fontenot v. NCAA Case Will Proceed Outside of House Settlement, On3 (May 23, 2024), https://perma.cc/ZR9L-WZQQ.

In fact, several athletes are currently doing just that. On May 23, 2024, Judge Charlotte N. Sweeney, a federal district court judge sitting in the district of Colorado, declined to send Fontenot v. NCAA180Fontenot v. NCAA, No. 1:23-cv-03076 (D. Colo. filed Nov. 23, 2023).—a separate case currently challenging the NCAA’s arbitrary cap on revenue sharing—to California.181Courtroom Minutes, Fontenot v. NCAA, No. 1:23-cv-03076 (D. Colo. filed May 23, 2024) (refusing the defendant’s motion to transfer under 28 U.S.C. § 1404(a), the federal change of venue statute). In effect, this decision prevented a merger of Fontenot with House (a merger that would have ultimately bound Fontenotwith the settlement). Judge Sweeney’s disapproval of a merger of the two cases means that as long as Fontenot remains separate, it creates a separate path for athletes who wish to opt out of the House settlement and pursue a better deal.182Prisbell, supra note 179. Boise State sports law professor Sam Ehrlich said of Fontenot:

Maybe it stays small, but if anything [Fontenot] certainly weakens the idea that the House settlement represents an end to antitrust litigation against the NCAA over amateurism rules, and bolsters any dissent (to the extent it exists) on the athletes’ side against the settlement. That can’t be extremely comfortable for the NCAA to hear on the day that I’m sure they were looking to start moving closer towards the settlement.183Id.

However, this decision—whether to opt in to House or not—creates a real dilemma for athletes. The House settlement is a sure bet. But an athlete who opts out of the settlement and “forgoes all of [its benefits,] . . . has to decide can they do better[,] . . . . [a]nd must do so on an individual basis and not as a class.”184Id. Steve Berman, Kessler’s co-counsel for the plaintiffs in House, believes that advising an athlete to opt out in hopes of getting more money—and incurring the litigation costs that necessarily come with a separate suit—would be “irresponsible.”185Id.

Yet Fontenot is picking up traction. In their amended complaint, plaintiffs’ lawyers recognize the hypocrisy of the House settlement: Even though the House settlement was approved, “it . . . usher[s] in a new, artificially low cap that is far below the revenue sharing that a competitive market would yield. While it is an admission that amateurism is not needed, it also simply substitutes one illegal price fix for another.”186See Second Amended Class Action Complaint at 25, Fontenot v. NCAA, No. 1:23-cv-03076 (D. Colo. filed July 23, 2024). Fontenot instead “takes aim at the full cut of television and other revenues that the athletes would receive in a truly open market.”187Id. at 26. The Fontenot attorneys recently added Sarah Fuller—the former Vanderbilt soccer player who became the first female to score in a Power Five football game by kicking an extra point—as a plaintiff.188See id. at 31; Chase Goodbread, Vanderbilt’s Sarah Fuller Becomes First Woman to Score in a Power Five Game, NFL (Dec. 12, 2020, 8:14 PM), https://perma.cc/H59D-G2XY. Adding more high-profile plaintiffs could become key in fighting back against the House settlement and convincing athletes to pursue a better deal in lieu of the safe harbor House represents.

Athletes who do choose to opt in to House will have to live with that choice. As explained, the settlement will prevent athletes from suing the NCAA on the issues in the settlement’s subject matter, cap the revenue they are entitled to, and leave it entirely up to the schools to determine how much they get.189See supra text accompanying notes 168–69. However, if there is no federal legislation involved, opting into the House settlement is the “safest” option for the athletes, if not the most lucrative.

B. Reform Through the Federal Government—Considering Options for Distributing Payment to Student-Athletes

As explained, the House settlement continues to be an antitrust violation because it arbitrarily caps revenues.190See supra Section IV.A. But the federal government could elect to regulate the collegiate athletic space, and supplement—or even preempt—the House settlement, if Congress or a regulatory body such as the FTC chooses to do so. Indeed, NCAA president Charlie Baker openly stated that he hopes the House settlement will inspire Congress to pass a federal bill regulating the space.191See Murphy, supra note 161. This Section considers the merits of several systems the feds could implement—analyzing revenue-sharing agreements, education-based incentives, and athletic-based incentives. Section V.C, infra, then argues that a revenue-sharing agreement would be the easiest, fairest, and most effective way to implement student-athlete compensation. In short, House got the remedy correct but got the price cap wrong.

Revenue-sharing agreements—a system where student-athletes who create revenue are given a direct proportional share of that revenue—like the one ultimately agreed to in House, are one way to distribute student-athlete-generated spoils. A version of this system has been introduced in Congress, but failed to get out of committee.192See College Athletes Bill of Rights, S. 4724, 117th Cong. § 5(a)–(b) (2022); S. 4724 (117th): College Athletes Bill of Rights,GovTrack.US, https://perma.cc/MQZ7-ZE3E (“The bill was not enacted into law.”). That failure was partially due some members of Congress still clinging to the amateurism principals of old.193See Dan Wolken, Memo to Joe Manchin, Congress: Stop Clutching Your Pearls as College Athletes Make Money, USA Today (Oct. 17, 2023, 6:40 PM), https://perma.cc/P6NY-KDC2. For example, on October 17, 2023, Senator Joe Manchin asserted in a congressional hearing that “it’s getting hard to root for the kids when they’re multi-millionaires as freshman and sophomores.”194Id. Manchin commuted to the Capitol that day from his 65-foot yacht docked in Washington, D.C.195Id.

Again, it helps to pause and highlight the difference here: Congress has the authority to grant antitrust exemptions and to regulate collegiate athletics through the commerce clause; but without federal intervention, the NCAA cannot unilaterally decide to be exempt from the Sherman Act.196See NCAA v. Alston, 141 S. Ct. 2141, 2160 (2021) (Kavanaugh, J., concurring). A revenue-sharing agreement put in place by the feds is lawful; a capped revenue-sharing agreement put in place by the NCAA is not. In the words of Justice Kavanaugh: “The NCAA is free to argue that, ‘because of the special characteristics of [its] particular industry,’ it should be exempt from the usual operation of the antitrust laws—but that appeal is ‘properly addressed to Congress.’”197Id. (alteration in original) (quoting Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 689 (1978)).

Many challenge revenue sharing, insisting that colleges should not trust young athletes with large sums of money because they may squander it in their youthful pursuits.198See, e.g., Kevin Doran, Should College Athletes Be Paid?, SLAM (Mar. 23, 2011), https://perma.cc/RZ52-ZPDW (“Despite [a particular coach’s] defense of the idea of paying student-athletes salaries, these same students are continuously making poor irresponsible decisions. Society cannot afford to pay athletes who are being looked up to by countless children across the nation who are indirectly led to believe that student-athletes’ behaviors are acceptable.”). If the federal government decided to give any merit to this claim—a claim which is dubious at best199Sports economist Andy Schwarz argues that the common myth that student-athletes are not responsible enough to manage their money and will simply “blow it all on bling and drugs” is illogical and rooted in racism. See Andy Schwarz, Excuses, Not Reasons: 13 Myths About (Not) Paying College Athletes, TEA WITH DR. G, https://perma.cc/3P6B-GLBP. “What the proponents of this argument are really saying is that they are uncomfortable with poor African-American adult men, suddenly earning more money than they’ve ever had before, and facing tough decisions about how to spend or save that money.” Id.—schools could instead distribute revenue into a trust that would be available to athletes upon graduation. This would (1) ensure the entire sum of the money is preserved for the athletes at the end of their collegiate career and (2) ensure that athletes focus on school rather than entirely on sports. The athletes would receive access to their fair share of the trust only upon graduation, so they must try hard enough in school to graduate. While the athletes are in school, an independent trustee could manage the trust.200See, e.g., Where Does the Money Go?, NCAA: Finances, https://perma.cc/PPE5-LMUA.

One complication with a revenue-sharing agreement is dealing with athletic programs that do not actually make money; with some rare exceptions, the only revenue-generating sports in college athletics are men’s football and basketball.201Newman, supra note 151, at 42. To ensure fairness and promote equity and inclusivity across all athletic programs, some may argue that it would be unjust to allow schools to allocate all of the revenue exclusively to football and basketball.202See Schwarz, supra note 199, at 59–60. However, Schwarz argues that Title IX policies for other sports would not preclude only compensating football and basketball athletes because it “aims for gender equity in participation and the regulations offer three ways to comply, none of which speak directly to equal funding.” Id. at 60. The NCAA regime under the House settlement will certainly face this issue—as schools begin to distribute 22% of their revenue however they want, difficult decisions will be made.203See Murphy, supra note 161. After all, if Alabama decides to give all 22% of the revenue to its football program, it will retain (and recruit) more football talent than a competitor SEC program that decides to give, say, 5% to the rowing program.

While the equity argument has merit, legislators might elect to create a bright-line rule and leave revenue distribution up to market forces, enacting a system that looks like House, but without a revenue cap. Even though in that model, only the sports that generate revenue are likely to seriously benefit from revenue sharing, the other athletes could continue to pursue compensation through athletic scholarships and separate NIL deals from outside sources.204See Taylor P. Thompson, Maximizing NIL Rights for College Athletes, 107 Iowa L. Rev. 1347, 1376–78 (2022). Further, colleges could then focus on attempting to draw outside viewership to other sports like baseball, softball, volleyball, swimming, and gymnastics, and once these programs became profitable, that revenue could then be shared with competitors.205Seeid. at 1380–82. A bright-line rule would also ensure fair compensation is distributed to the high-profile football and basketball athletes, who compete in two of the most physical sports, and have among the highest rates of injury.206SeeJennifer M. Hootman, Randall Dick & Julie Agel, Epidemiology of Collegiate Injuries for 15 Sports: Summary and Recommendations for Injury Prevention Initiatives, 42 J. Athletic Training 311, 316 (2007).

2. Implementing Education-Based Incentives

Education-based incentives are another option. More than any other proposed system, an education-based regime has the best chance to pacify those still clinging to amateurism because, as discussed, the entire amateurism philosophy was built on the principle that student-athletes should be students first and athletes second.207See supra Part I. Even though amateurism is largely a farce in the current athletic landscape,208See supra Section III.A. this system would provide an amateurism-friendly headline and allow naysayers to quietly put down the pitchforks.

There are multiple ways to implement an education-based reward system. Athletes could (1) receive bonuses based on their academic performance, (2) be compensated based on whether they meet a minimum GPA requirement, or (3) be given the dedicated funds based on a tier system—that is, higher grades means more compensation (money).209Madison Williams, 22 FBS-Level Schools Plan to Give Athletes Academic Bonus Payments, Sports Illustrated (Apr. 6, 2022), https://perma.cc/8R69-SZTB. Schools could quantify performance in comparison to other athletes on the team, or even in comparison to other athletes in the same athletic conference. If a player is an All-Conference academic star, then that player would earn the biggest monetary bonus.

Or, compensation could be based on tangible intra-university accomplishments. For example, making the Dean’s List or President’s List, completing a personal finance course, or successfully graduating from the university could control whether an athlete is paid out from the revenue fund. Finally, athletes could receive funds for engaging in community service, completing extra tutoring, or participating in other academic extracurriculars. Regardless of the implementation method, this could be a “middle ground” between amateurism fans and their more free-market adversaries.