Introduction

The Supreme Court is coming for the administrative state. Across a variety of doctrines, the Court has narrowed the administrative state’s operating space. It has imposed limits on how agencies may be structured, how they may be staffed, and the types of authority they may exercise. And now, in Relentless v. Department of Commerce162 F.4th 621 (1st Cir. 2023), cert. granted in part, 144 S. Ct. 325 (argued Jan. 17, 2024) (mem.). and Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo,245 F.4th 359, 363 (D.C. Cir. 2022), cert. granted in part, 143 S. Ct. 2429 (argued Jan. 17, 2024) (mem.). the Supreme Court appears poised to eliminate the Chevron doctrine, one of the signature elements of administrative law for nearly forty years. Chevron is, without question, the administrative law doctrine with the greatest name recognition.3Jack M. Beermann, Chevron at the Roberts Court: Still Failing After All These Years, 83 Fordham L. Rev. 731, 731 (2014) (“[T]he Chevron decision has been the most-cited Supreme Court administrative law decision, and the Chevron doctrine has spawned legions of law review articles analyzing its numerous twists and turns.”). Among administrative law experts and casual observers, the possibility that it will be overturned likely looms larger than any other potential administrative law development (though the Major Questions Doctrine may be in hot pursuit). The assault on Chevron is widely viewed as yet another impingement by the Court on agencies’ ability to do their jobs—principally, regulating risks to health and safety in the national interest.4E.g., Edward T. Hayes, International Law, 71 La. B.J. 132, 133 (2023) (“Overturning or limiting Chevron would restrict administrative agencies’ ability to create administrative regulations.”); Scott Abeles, Chevron on the Brink—the Supreme Court Could Revolutionize Administrative Law this Term (but Shouldn’t), Westlaw Today, Oct. 12, 2023, at 2 (“Agencies have regulated, and business has ordered their affairs, against the background of Chevron for nearly 40 years.”).

Repealing Chevron would indeed restrict agencies’ operating freedom. Rather than being able to select any reasonable statutory meaning and regulate accordingly, agencies would be confined to whatever a reviewing court believes is the regulatory statute’s “best” meaning.5Nat’l Cable & Telecomms. Ass’n v. Brand X Internet Servs., 545 U.S. 967, 1018 (2005) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (“Of course, like Mead itself, today’s novelty in belated remediation of Mead creates many uncertainties to bedevil the lower courts. A court’s interpretation is conclusive, the Court says, only if it holds that interpretation to be ‘the only permissible reading of the statute,’ and not if it merely holds it to be ‘the best reading.’”). Yet there is a critical difference between the impending repeal of Chevron in Relentless and these other prongs of the assault on the administrative state. While repealing Chevron will diminish agencies’ freedom to operate, it will not necessarily diminish the overall quantity or level of stringency of regulation in the United States. That is, the Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) might have fewer options when selecting a program of regulation. But that does not necessarily mean that the level of regulatory protection experienced by Americans will decline.

The reason is that the principal effect of repealing Chevron will be to entrench the status quo. That effect is not necessarily deregulatory or anti-regulatory. Rather, the current regulatory landscape is robust across a wide variety of domains, with significant health and safety regulation in place. Importantly, there is a great deal more regulation now than when the Court decided Chevron during the Reagan administration.6See generally Reg Stats, Geo. Wash. Univ. Regul. Stud. Ctr., https://perma.cc/3JFY-VBEL (graphing increases in regulatory budget outlays and total pages in the Code of Federal Regulations and Federal Register in recent decades). Chevron’s repeal, if that is what comes, will impede agencies from promulgating further regulation. But it will also impede them from eliminating existing regulation. That fact, which has gone largely unremarked amidst the furor over Relentless, is critical to assessing the future of the regulatory state in a world without Chevron.

This short Article proceeds in three Parts. Part I describes the many ways, other than repealing Chevron, in which modern administrative law doctrine has been deployed to limit the reach and power of the administrative state other than repealing Chevron. Part II explains how Chevron is two-sided and can be used as a tool to serve either regulatory or deregulatory ends. Finally, Part III offers a set of predictions as to what the world after Chevron might look like if it is repealed in Relentless.

I. The Multi-Pronged Assault on the Administrative State

Over the past fifteen years, the Supreme Court’s effort to roll back the administrative state has encompassed five separate doctrines. One is Chevron deference, the focus of this Article. Before turning to Chevron, however, this Article canvases the four other doctrines. The point of doing so is to highlight how the Supreme Court’s interventions in these other doctrines have produced unequivocally anti-regulatory effects. That is not necessarily the case for Chevron, as this Article argues. The four non-Chevron prongs of the Supreme Court’s assault on the administrative state are:

(1) The Major Questions Doctrine. In 1935, the Supreme Court infamously struck down two sections of the National Industrial Recovery Act—a significant piece of New Deal legislation—on the ground that they violated the “nondelegation doctrine,” which (according to the Court) barred Congress from delegating legislative authority to executive-branch agencies.7A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495, 529, 541–42 (1935); Pan. Refin. Co. v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388, 421, 430 (1935). The nondelegation doctrine then became a dead letter; eighty-seven years passed without the Court striking down another congressional delegation of authority.8Cass R. Sunstein, Is the Clean Air Act Unconstitutional?, 98 Mich. L. Rev. 303, 330-34 (1999) (noting that the nondelegation doctrine had “one good year”). In 2022, however, in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency,9597 U.S. 697 (2022). the Supreme Court reanimated the nondelegation doctrine, this time as a clear statement rule—the major questions doctrine.10Id. at 724. The Court held that if an agency claimed authority to regulate regarding a “major question,” one that was controversial and involved significant economic impact, its claim to authority must be backed by explicit statutory language.11Id. at 721, 723. Unlike the original nondelegation doctrine of 1935, the Court did not hold that Congress was forbidden to delegate certain powers to agencies; Congress could do so, so long as it spoke clearly.12Id. But in light of the sweeping and ambiguous language that characterizes many organic administrative statutes, the effect may be the same—at least as to existing law. Also, there is no reason to believe the Court will necessarily stop here. This iteration of the major questions doctrine could be a waystation to a comprehensive nondelegation doctrine in which certain administrative allocations of power are simply forbidden.

(2) The Spending Clause. In Community Financial Services Ass’n v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau,1351 F.4th 616 (5th Cir. 2022). the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit held that the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (“CFPB’s”) “self-funding” structure violated the Appropriations Clause of the Constitution.14Id. at 625, 638–40; see U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 7. That clause specifies that “[n]o money may be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”15U.S. Const. art. I, § 9, cl. 7. Many agencies, including most executive-branch agencies, receive their funding through annual appropriations enacted into law by Congress.16Matthew B. Lawrence, Congress’s Domain: Appropriations, Time, and Chevron, 70 Duke L.J. 1057, 1059 (2021). Some agencies, however, are funded through other mechanisms. For instance, the CFPB requests and receives funding from the Federal Reserve.1712 U.S.C. § 5497(a)(1). The Federal Reserve, in turn, obtains funds through its open market activities, but it “is required to remit surplus funds in excess of a limit set by Congress” to the Treasury.18Cmty. Fin. Servs. Ass’n of Am., Ltd. v. CFPB, 51 F.4th 616, 638 (5th Cir. 2022). Accordingly, money that might otherwise wind up in the Treasury is instead obtained and spent by the CFPB.

The Supreme Court granted certiorari heard this case during its October 2023 term.19143 S. Ct. 978 (2023). At the time of this writing, the case has been argued but not yet decided. If it agrees with the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit that this type of spending arrangement violates the Appropriations Clause, the Court could endanger the ongoing existence and operations of the CFPB and a constellation of other federal agencies. For example, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”) receives funding via levies against the banks whose deposits it insures.20Brief for Petitioners at 32–33, CFPB v. Cmty. Fin. Servs. Ass’n of Am., Ltd., No. 22-448 (May 8, 2023). The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) is funded via application and maintenance fees collected from patent and trademark applicants and owners (though congressional authorization is typically necessary before the USPTO can access those funds).21Jonathan S. Masur, CBA at the PTO, 65 Duke L.J. 1701, 1721 (2016). Perhaps most importantly, the Federal Reserve is self-funded via revenues from its open market operations.22See Peter Conti-Brown, The Institutions of Federal Reserve Independence, 32 Yale J. Reg. 257, 284 (2015). It is impossible to know yet whether this line of assault against the administrative state will blossom in the Supreme Court. But if it does, it goes without saying that this line of doctrine would represent yet another critical curtailment of agencies’ ability to regulate—or, in some cases, even to exist.

(3) The President’s Removal Power. In Humphrey’s Executor v. United States23295 U.S. 602 (1935). and Morrison v. Olson24487 U.S. 654 (1988).—decided in 1935 and 1988, respectively—the Supreme Court held and then affirmed that Congress could insulate agency heads from removal at will by the President.25See Humphrey’s Executor, 295 U.S. at 632; Morrison, 487 U.S. at 659–60. This authority should be understood as a boon to regulatory decision-making. Some agencies, such as the Federal Election Commission, likely would not exist if their heads had to answer to the President.26For an overview of the Federal Election Commission, see Lee Ann Elliott, Federal Election Commission, Update on L. Related Educ., Fall 1996, at 8. Others, such as the Federal Reserve, would almost certainly not function as well if they were caught up in everyday politics.27See Conti-Brown, supra note 22, at 263–64. Nonetheless, in 2010, the Supreme Court held in Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Companies Accounting Oversight Board28561 U.S. 477 (2010). that Congress could not create agencies that were insulated by a double layer of removal protection, with one agency’s members only removable for cause by the members of another agency who are themselves only removable for cause.29See id. at 484. And in 2020, the Court held in Seila Law v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau30140 S. Ct. 2183 (2020). that Congress could not make single-member agency heads removable only for cause, Morrison and Humphrey’s notwithstanding.31See id. at 2201. Only multi-member bodies such as the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) could have members who were removable only for cause.32See id. at 2199–200; see also id. at 2236 (Kagan, J., dissenting).

Free Enterprise and Seila Law together implicate only a few of the many independent federal agencies. As a result, this line of assault has not yet had a substantial impact on the administrative state. Nonetheless, there is no reason to believe the Court will stop here. It is not difficult to imagine the Court handing down further decisions that would imperil the SEC, Federal Communications Commission, Federal Reserve, and other multi-member independent agencies headed by officials who are removable only for cause.

(4) The Appointments Clause. In a pair of cases, the Supreme Court has held that various administrative employees are “Officers of the United States” under the Appointments Clause and, thus, that the procedures used to appoint them were unlawful.33U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2. In Lucia v. Securities and Exchange Commission,34138 S. Ct. 2044 (2018). the Court held that administrative law judges were inferior officers of the United States when vested with authority to oversee enforcement proceedings against private companies rather than mere employees.35Id. at 2051–55. Because the administrative law judges in question had been selected by SEC staff members rather than by the President or SEC Commissioners, they had not been lawfully been appointed, and their exercise of authority was unlawful.36Id. In United States v. Arthrex,37141 S. Ct. 1970 (2021). the Court similarly held that administrative patent judges were principal officers of the United States due to the power they possessed to decide cases involving the validity of patents brought before the USPTO.38Id. at 1985–86. Principal officers must be appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate, and because administrative patent judges had not been appointed in this fashion their exercise of authority was similarly deemed unlawful.39Id.

In both cases, the government quickly found workarounds to allow the agencies in question to continue functioning. After Lucia, the heads of agencies that employed administrative law judges issued pro forma orders, effectively rubber-stamping the appointment of those administrative law judges.40Jack M. Beermann & Jennifer L. Mascott, Research Report on Federal Agency ALJ Hiring after Lucia and Executive Order 13843, Admin. Conf. U.S., May 31, 2019, at 21–22. This satisfied the requirement that inferior officers be appointed by “Heads of Departments” (if not by the President or the courts).41U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2. In Arthrex, the Supreme Court blessed the lower court’s decision to make administrative patent judge decisions reviewable (and subject to being overturned) by the USPTO Director.42Arthrex, 141 S. Ct. at 1987–88. This rendered administrative patent judges inferior officers under the Appointments Clause, curing the constitutional defect.43See id.

Yet while these fixes were quick and relatively painless, that may not always be the case. For instance, if the Court had rejected the solution in Arthrex of making administrative patent judge decisions reviewable, the President might have had to appoint each patent judge individually, with the advice and consent of the Senate.44U.S. Const. art. II, § 2, cl. 2. This would have been a time-consuming and disruptive process, during which time the USPTO could not have adjudicated patent disputes. For that matter, if the Court had held administrative law judges to be principal officers rather than inferior officers, restoring their authority might have been significantly more arduous as well. Accordingly, this line of doctrine poses a latent threat to the operation of the administrative state as it currently exists, even if that threat has not yet fully materialized.

The four burgeoning lines of doctrine described above share a common characteristic: they will all make it more difficult for agencies to regulate. In some cases, they do so by limiting the forms that federal administrative agencies may take (and thus the options available to Congress); in others, they do so by limiting the powers afforded to agencies under existing (or future) statutes. But every one of these doctrines is a one-way ratchet: the tighter the doctrine, the less room for agency action. As the next Part argues, the same cannot be said for Chevron.

II. The Double-Sided Nature of Chevron

Chevron is a grant of flexibility to agencies. It provides interpretive space and room to operate. Instead of being forced to regulate according to whatever a court believes is the best interpretation of a statute, an agency may select from among any of the reasonable interpretations of a statute and regulate according to that statutory meaning.45Nat’l Cable & Telecomms. Ass’n v. Brand X Internet Servs., 545 U.S. 967, 1018 (2005) (Scalia, J., dissenting). At first glance, it might seem as though Chevron is an important pro-regulatory doctrine and that eliminating it would have substantial anti-regulatory effects. Indeed, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this is how every pro-regulatory scholar has described the role of Chevron and the likely effects of Relentless.46See, e.g., Kent Barnett & Christopher Walker, Chevron and Stare Decisis, 31 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 475, 486, 492–93 (2024); Liza Schultz Bressman, Lower Courts After Loper Bright, 31 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 499, 500 (2024); John F. Duffy, Chevron, De Novo: Delegation, Not Deference, 31 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 541 (2024); Daniel E. Walters, Four Futures of Chevron Deference, 31 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 635, 637–38 (2024), for further reading on the regulatory effects of Chevron and its potential elimination.

Yet this consensus is not correct. Rather, the question of whether Chevron is pro-regulatory (or not) depends upon (a) the existing regulatory baseline and (b) who is sitting in the Oval Office. That is, Chevron is not fundamentally or intrinsically either pro-regulatory or anti-regulatory. Its effects are contingent.

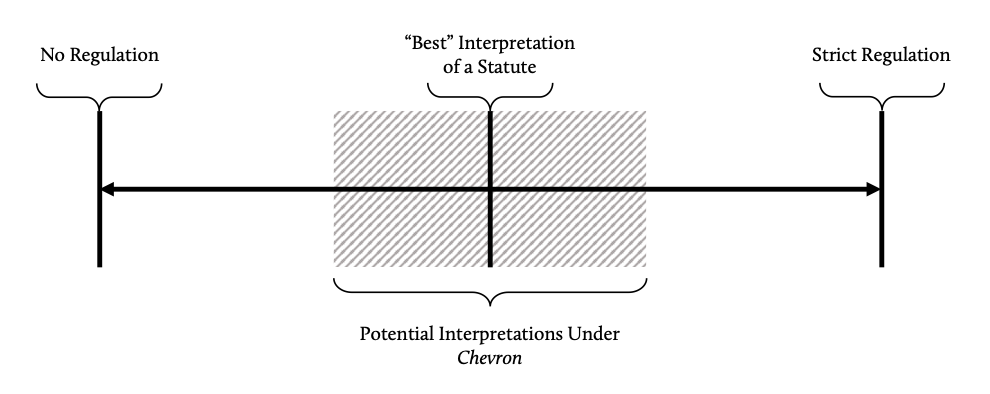

Begin by considering a hypothetical world in which no regulation (or very little regulation) exists. For a regulatory agency, the only way to go is up. There is nothing to deregulate, so any action the agency takes will necessarily be regulatory. Under these circumstances, Chevron—with its grant of flexibility to agencies—will necessarily be a pro-regulatory doctrine. It will provide agencies with more options and allow them to stretch their regulatory reach more broadly. To illustrate the point graphically, imagine the various regulatory options facing some agency (the EPA, for instance) under some provision of a regulatory statute (the Clean Air Act, for instance). One could array those options on a line from less stringent to more stringent. Whatever the “best” interpretation of the statute might dictate, Chevron opens up options on either side of that “best” interpretation and provides the agency with greater regulatory alternatives. And importantly, all of these regulatory options are more stringent than the status quo, which is zero regulation.

Figure 1: Regulatory Options Under Chevron

Now, imagine a world in which substantial regulation already exists. In this not-so-hypothetical world, most known health and safety hazards are being regulated by federal agencies to some degree, even if not to the optimal extent. At any given moment, an agency thus has two options: (1) it could regulate further, leading to more stringent health and safety regulations, or (2) it could deregulate, leading to less stringent health and safety regulations. The choice between these two options is, of course, a political one determined by who is President and whom that President chooses to appoint to head the various federal regulatory agencies. But the crucial point is that Chevron offers flexibility to an agency whether that agency has chosen to regulate or deregulate. In this respect, Chevron is symmetrical. It offers an agency a range of options that are more stringent than what would be dictated by the “best” interpretation of the statute, and it offers an agency a range of options that are less stringent than the “best” interpretation. Depending on the President, Chevron is equally potent as either a deregulatory or regulatory tool.

This is not merely a hypothetical possibility. Nearly every presidential administration from 1988 until 2016 was predominantly pro-regulatory, despite the various political leanings of the individuals who were President during that period.47See William Laffer, George Bush’s Hidden Tax: The Explosion in Regulation, Heritage Found. (July 10, 1992), https://perma.cc/3UG2-4EA6; see also Robert J. Duffy, Regulatory Oversight in the Clinton Administration, 27 Presidential Stud. Q. 71, 71–72 (1997); Susan E. Dudley, The Bush Administration Regulatory Record, Mercatus Reps., Winter 2004, at 8; President Obama’s Regulatory Output: Looking Back at 2015 and Ahead to 2016, Geo. Wash. Univ. Regul. Stud. Ctr. (Jan. 13, 2016), https://perma.cc/5CQM-ZJCK; Executive Orders, Fed. Reg., https://perma.cc/75EF-4KMB (showing the number of executive orders signed by each President since William J. Clinton). Even Presidents George H.W. and George W. Bush engaged in little administrative deregulation and substantial new regulation.48See Laffer, supra note 47; see also Dudley, supra note 47, at 8. But this trend ended when President Donald Trump was elected in 2016.49See Phillip A. Wallach & Kelly Kennedy, Examining Some of Trump’s Deregulation Efforts: Lessons from the Brookings Deregulation Tracker, Brookings Inst. (Mar. 8, 2022), https://perma.cc/MM8B-BH9L. Trump had made deregulation a substantial part of his campaign agenda.50See Keith B. Belton & John D. Graham, Deregulation Under Trump, Regulation, Summer 2020, at 14; Lydia Wheeler & Lisa Hagen, Trump Signs ‘2-for-1’ Order to Reduce Regulations, Hill (Jan. 30, 2017, 1:09 PM), https://perma.cc/N74A-B6SP. This included promising such arbitrary goals as eliminating two regulations for every new regulation promulgated and requiring that the costs of any new regulation be fully paid for by eliminating some other regulation with equal or greater costs, never mind what benefits these regulations might confer.51Wheeler & Hagen, supra note 50; Jonathan S. Masur, The Deep Incoherence of Trump’s Executive Order on Regulation, Yale J. on Regul.: Notice & Comment (Feb. 7, 2017), https://perma.cc/TEK2-2576. It also included more substantive objectives focused on repealing various regulations promulgated by the Obama administration.52Jonathan S. Masur & Eric A. Posner, Chevronizing Around Cost-Benefit Analysis, 70 Duke L.J. 1109, 1114–15 (2021). Perhaps the most notable of Trump’s targets was the Clean Power Plan, President Barack Obama’s signature climate change-focused regulation.53See id. at 1120–21; Carbon Pollution Emission Guidelines for Existing Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units, 80 Fed. Reg. 64662 (Oct. 23, 2015) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 60). But Trump also took aim at a wide variety of other Obama-era regulations, including improvements to fuel economy standards and regulations of mercury emissions from coal-fired power plants.54Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1117–19, 1127–28; see also National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Coal- and Oil-Fired Electric Utility Steam Generating Units–Reconsideration of Supplemental Finding and Residual Risk and Technology Review, 85 Fed. Reg. 31286 (May 22, 2020) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 63); The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule for Model Years 2021–2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks, 85 Fed. Reg. 24174 (Apr. 30, 2020) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pts. 86, 300; 49 C.F.R. pts. 523, 531, 536–37).

With respect to several of these deregulations, the principal legal tool employed by the Trump administration was Chevron.55Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1138–39. For instance, Obama’s mercury emission regulation was promulgated under a provision of the Clean Air Act requiring that regulation be “appropriate and necessary.”56Michigan v. EPA, 576 U.S. 743, 749 (2015); see Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7412(n)(1)(A). In rescinding this regulation, the Trump EPA argued that “appropriate and necessary” should be interpreted to mean that the agency could only consider the impact of the regulation in reducing mercury emissions—the regulation’s primary objective—and not whatever ancillary benefits it might produce.57National Emission Standards for Hazardous Air Pollutants: Coal- and Oil-Fired Electric Utility Steam Generating Units–Reconsideration of Supplemental Finding and Residual Risk and Technology Review, 84 Fed. Reg. 2670, 2670, 2677 (proposed Feb. 7, 2019) (to be codified at 40 C.F.R. pt. 63). This was a significant step because a regulation that reduces the amount of mercury emitted by coal-fired power plants also reduces the emissions of several other extraordinarily harmful pollutants, including particulate matter and carbon dioxide.58Id.; see also Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1121. Taken as a whole, the regulation was expected to produce extraordinary benefits to human health and safety.59Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1121. But if one considered the benefits of reducing mercury alone, the benefits of the regulation would seem outweighed by its costs. From that narrow point of view, the regulation might not seem “appropriate and necessary.”

This reading of “appropriate and necessary” to mandate the exclusion of ancillary benefits may or may not have been a reasonable reading of an ambiguous statute. However, it is almost surely not the best or most natural reading of the statute. Chevron deference was thus essential to the Trump EPA’s efforts to rescind the Obama mercury regulation.60Id. at 1138. The Trump administration was quite explicit about its efforts to use Chevron in this fashion.61Id.

The Trump administration took a similar approach to Obama-era fuel economy regulations. The Clean Air Act provides California with statutory authority to seek a “waiver”—really, an exemption—permitting it to impose air quality standards that are stricter than national standards without being preempted by federal law.62Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7543(b)(1). This includes fuel economy standards, which have an obvious impact on air quality.63Molly A. Seltzer, Comprehensive Look at U.S. Fuel Economy Standards Shows Big Savings on Fuel and Emissions, Princeton Univ. Andlinger Ctr. for Energy & Env’t (Aug. 25, 2020), https://perma.cc/H8S8-CHWR. California has sought and received waivers on dozens of occasions, including during the Obama administration.64Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1132–33; see also California Greenhouse Gas Waiver Request, EPA, https://perma.cc/J44K-R99D (discussing Californian waivers and providing related documents associated with waiver requests). These waivers significantly impact national fuel economy standards because of the size and importance of the California market for automobiles.65Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1145–46. Irrespective of federal fuel economy standards, if California imposes stringent requirements, automakers must follow those standards or risk being shut out of the California market.66Id. at 1133.

The Obama EPA and Department of Transportation (“DOT”) had promulgated new, more stringent federal fuel economy regulations.67Id. at 1125–27. Trump’s EPA and DOT repealed those regulations and replaced them with much weaker fuel economy standards.68Id. at 1127. But as the previous paragraph explains, to actually implement weaker fuel economy standards nationwide, the Trump EPA also needed to withdraw California’s Clean Air Act waiver.

In September 2019, the Trump administration announced it was doing just that.69The Safer Affordable Fuel-Efficient (SAFE) Vehicles Rule Part One: One National Program, 84 Fed. Reg. 51310 (Sept. 27, 2019) (codified at 40 C.F.R. pts. 85–86; 49 C.F.R. pts. 531, 533). The Clean Air Act specifies that California may obtain a waiver when it faces “compelling and extraordinary conditions.”70Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7543(b)(1)(B). In withdrawing California’s waiver, the Trump administration argued that “extraordinary” meant that California must face conditions distinct from other states and particular to California.71Masur & Posner, supra note 52, at 1144–45. Because California intended to use higher fuel economy standards to address the problem of climate change, and because climate change is a global issue, the Trump administration claimed that California did not face “extraordinary conditions.”72Id. Here, too, the Trump EPA argued that it had authority under Chevron to interpret the statute in this manner.73Id. Again, Chevron deference was the centerpiece of Trump’s deregulatory efforts.

The conclusion to be drawn from these examples is that the net effect of Chevron depends greatly on who occupies the White House. Against a backdrop of substantial regulation across the economy—much more true in 2023 than in 1984—a pro-regulatory President can use Chevron to regulate more stringently, and a deregulatory President can use it to deregulate or regulate less stringently. In an era of hyper-partisanship, in which the political parties define themselves ever more starkly in opposition to one another and the regulatory agenda is a significant battleground, it has become particularly likely that Democratic Presidents will emphasize more stringent regulation and Republican Presidents will emphasize deregulation. If Chevron were to remain in force, the result could well be a type of oscillation between more and less stringent regulatory regimes as the party in control of the White House switches back and forth.74Jonathan S. Masur, Regulatory Oscillation, 39 Yale J. on Regul. 743, 747 (2022).

III. The Aftermath of Relentless

What, then, should we expect if the Supreme Court uses Relentless as a vehicle to overrule Chevron, as has been widely predicted? In the short run, the likely outcome is a great deal of uncertainty and a fair amount of churn. A wide variety of existing regulations, including many whose legality was originally upheld under Chevron, are likely to come under assault. There is a general six-year statute of limitations for civil actions brought against the United States.7528 U.S.C. § 2401(a); see also 5 U.S.C. § 702; Nat’l Ass’n of Mfrs. v. Dep’t of Def., 583 U.S. 109, 118–19 (2018) (holding that the six-year statute of limitations applies to challenges brought under the Administrative Procedure Act). However, there is a circuit split on when that six-year limitations period begins to run. Some courts have held that the statute of limitations begins to run when a regulation is finalized.76E.g., P & V Enters. v. U.S. Army Corps of Eng’rs, 466 F. Supp. 2d 134, 142 (D.D.C. 2006), aff’d, 516 F.3d 1021 (D.C. Cir. 2008). Others have held that the statute of limitations begins to run only when the party bringing suit has been injured by agency action.77Dunn–McCampbell Royalty Int., Inc. v. Nat’l Park Serv., 112 F.3d 1283, 1287 (5th Cir. 1997) (“[T]he claimant must show some direct, final agency action involving the particular plaintiff within six years of filing suit.”); Wind River Mining Corp. v. United States, 946 F.2d 710, 715 (9th Cir. 1991) (“[A] challenger contest[ing] the substance of an agency decision as exceeding constitutional or statutory authority . . . may do so later than six years following the decision by filing a complaint for review of the adverse application of the decision to the particular challenger.”). At the time of this writing, the Supreme Court has heard argument but not yet decided a case that should resolve this circuit split.78Corner Post, Inc. v. Bd. of Governors of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., 144 S. Ct. 478 (argued Feb. 24, 2024) (mem.). It is impossible to know with certainty how that case will be resolved, but it seems unlikely that the result will be to bar many regulatory challenges. Moreover, a decision upholding a regulation under Chevron deference is unlikely to exert much stare decisis force in a post-Chevron world. Consequently, a significant number of regulations—and existing precedents—are likely vulnerable.

At the same time, many of these regulations will likely survive in a world without Chevron. In many cases, the agency’s policy choice will be lawful even under the court’s construction of the statute. As described above, the Obama administration’s mercury regulation is one such example.79See supra notes 55–60 and accompanying text. If a regulation has been in operation for a substantial number of years and has produced positive results, an agency may be able to convince a court to adopt an interpretation of the governing statute that saves that regulation. In addition, many regulations are likely to go unchallenged because they are congenial to regulated parties.80For examples of regulations that regulated parties likely support because they merely entrench what the regulated parties are already doing, see Jonathan S. Masur & Eric A. Posner, Norming in Administrative Law, 68 Duke L.J. 1383 (2019). Thus, in the short term, there may not be quite as much upheaval as one might imagine.

In the longer term, Chevron’s demise will likely produce greater stability in regulatory policymaking. The courts will settle on some set of statutory meanings—all supporting some type of regulation and many likely supporting the status quo—even if these meanings do not support the most stringent or lenient regulations that a pro- or anti-regulatory administration would select. More to the point, the combined short- and long-term effects will likely entrench the status quo. Courts will likely be inclined to bless the current arrangement, thereby preventing strongly regulatory or deregulatory administrations from achieving their most boundary-pushing objectives. The current level of regulatory stringency may not be optimal in many or any sectors of the economy. But it is not zero, and in many realms it is roughly appropriate—workable and adequate. The impending demise of Chevron is more likely to stabilize this status quo than it is to upend it.

Conclusion

Chevron is the most famous decision in the history of administrative law, and so its impending demise has unsurprisingly made headlines. But the impact of Chevron—and its repeal—on the actual state of regulation is much more equivocal than scholars have recognized. In a world with a high baseline level of regulation, Chevron can be (and has been) a tool for regulation or deregulation. A world without Chevron will likely be business-as-usual for most agencies. The same cannot be said, however, for many of the other prongs of the Supreme Court’s assault on the administrative state. Those doctrines—particularly the major questions doctrine and the new Spending Clause cases—could dramatically upend the administrative state in a manner that cannot be easily undone. There is a certain irony in suggesting, at a symposium on Chevron, that scholars, advocates, and policymakers—whether pro- or anti-regulatory—should turn their attention away from Chevron and toward a separate constellation of cases. But that is precisely where the primary focus should lie.