Introduction

Beginning in the late 1970s, the Chicago School of Antitrust claims that it made a major contribution to making antitrust policy coherent and “scientific” by introducing basic economic concepts. It advanced both the Consumer Welfare Standard (a normative economic theory to segregate legitimate economic competition goals from “value judgments”) and a basic positive microeconomic theory to show how much of the conduct previously considered anticompetitive was justified on “efficiency” grounds.1Christopher S. Yoo, The Post-Chicago Antitrust Revolution: A Retrospective, 168 U. Pa. L. Rev. 2145, 2147–50 (2020). Its contributions had a major impact on the federal judiciary in the United States and the antitrust enforcement agencies that spread Consumer Welfare throughout the globe.

The Post-Chicago-School economists have not challenged the Consumer Welfare Standard. Instead, the Post-Chicago School has asserted that the Consumer Welfare Standard is redeemable—correctable for many of the overstatements and conservative political conclusions of the Chicago School.2See Michael S. Jacobs, Essay on the Normative Foundations of Antitrust Economics, 74 N.C. L. Rev. 219, 221–22 (1995). Proponents of the Post-Chicago School are fond of advancing the narrative that in the late 1980s and during the 1990s, major advancements occurred in industrial organization economics. Many of the earlier Chicago School conclusions required assumptions that were not evident from the Chicago School economists and were often not typical of the factual situations under scrutiny in antitrust cases.3Herbert Hovenkamp & Fiona Scott Morton, Framing the Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis, 168 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1843, 1850, 1858, 1871 (2020).

In the last decade, a third school of antitrust scholars, the “New Brandeisians,” perhaps drawing from literature ignored during these waves of economic theory, have made major headway in antitrust circles. The New Brandeisians accept the advances of the Post-Chicago economists but challenge Post-Chicago scholars’ devotion to the Consumer Welfare Standard and their understanding of antitrust history. New Brandeisians advocate instead that competition policy can address the traditional antitrust goals of political democracy and support small businesses.4See David Dayen, This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies, Nation (Apr. 4, 2017), https://perma.cc/RBR6-NB93; see also Aurelien Portuese, Biden Antitrust: The Paradox of the New Antitrust Populism, 29 Geo. Mason L. Rev. 1087, 1104 (2022). They further claim that antitrust enforcement should be used to protect labor and to address inequality when it is being exacerbated by a traditional antitrust violation.5See Amelia Miazad, Prosocial Antitrust, 73 Hastings L.J 1637, 1642–43 (2022).

Post-Chicago scholars have not embraced the New Brandeisians. Several papers by Post-Chicago scholars have emphasized that the New Brandeisians do not sufficiently adopt economic theory.6See, e.g., Joshua D. Wright, Elyse Dorsey, Jonathan Klick & Jan M. Rybnicek, Requiem for a Paradox: The Dubious Rise and Inevitable Fall of Hipster Antitrust, 51 Ariz. State L.J. 293, 313, 369 (2019); Carl Shapiro, Antitrust: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It, 35 Antitrust 33, 42 (2021). Post-Chicago scholars claim that, on economic grounds, they are the clear winners of this competition between competing analytical approaches because they are the only ones faithful to the latest developments in industrial organization.7See Shapiro, supra note 6, at 34–36. For example, in a recent paper, Professor Jonathan Baker, contrasting himself with the New Brandeisians, states that “[b]y contrast, post-Chicagoans embrace economics. Centrist reformers see economic analysis and economic evidence as essential for making the case for stronger antitrust rules and enforcement . . . .”8Jonathan B. Baker, Finding Common Ground Among Antitrust Reformers, 84 Antitrust L.J. 705, 744–45 (2022).

In this paper, we claim that economic theory—not just the sub-discipline of industrial organization—supports the New Brandeisians. Specifically, modern welfare economics warrants the abandonment of the Consumer Welfare Standard as antiquated and deeply and irrevocably flawed.

Moreover, economic history provides empirical evidence that the goals of the New Brandeisians will benefit the economy as a whole. While Post-Chicago claims about the limitations of the Chicago School are largely accurate, they limit economic theory to industrial, organization-applied microeconomics. Economics as a discipline is much broader and richer than these Consumer Welfare Standard advocates let on. By ignoring the larger discipline in economics and the advances that have taken place, antitrust discourse has been impoverished. The effect has been to cast the New Brandeisians as the outliers in terms of economic understanding when it is the case that they are the only school to have the bulk of economics on their side.

Part I of this article details the three schools of thought, starting with the Chicago School and the weaknesses of its antitrust theory. It then details the contributions of the Post-Chicago School while noting that the Post-Chicago School still clings to Consumer Welfare Theory to advocate for broader antitrust enforcement. The New Brandeisians advocate for policy goals outside of the realm of Consumer Welfare Theory, which we detail in this part as well.

Part II describes the progression of modern economic theory. Modern economic theory, apart from industrial organization and its disciples of Consumer Welfare, has long ago moved away from surplus approaches to welfare. Part II details this transformation in modern economics.

Part III describes economic history. The goal of this section is to demonstrate that the New Brandeisian goals are more aligned with historical evidence of a more robust society. In contrast, Neoliberal policies, of which Consumer Welfare Theory is a part, are associated with worse economic performance.

I. Developments in Industrial Organization Economics Favor the Post-Chicago School over the Chicago School

We begin by considering the origins and influence of the Chicago and Post-Chicago Schools of Antitrust. The Chicago School rapidly transformed much of antitrust policy despite decades of precedent. We contend developments in industrial organization show the superiority of the Post-Chicago analysis over the original Chicago School economics. Yet Post-Chicago Economics has been unable to exert much impact in the courts. The New Brandeisians are aligned with the Post-Chicago School’s positive economic contributions. Points of contention between the two, however, include the role of economics and the Post-Chicago School’s acceptance of the deeply flawed Consumer Welfare Standard.

A. The Chicago School: Origins, Influence, and Mispredictions

1. Origins

The Chicago School program emerged from the University of Chicago under the direction of Professor Aaron Director.9Sam Peltzman, Aaron Director’s Influence on Antitrust Policy, 48 J.L. & Econ. 313, 313–14 (2005). Friedrich Hayek was instrumental in Director’s recruitment.10Rob Van Horn & Philip Mirowski, The Rise of the Chicago School of Economics and the Birth of Neoliberalism, in The Road from Mont Pèlerin: The Making of the Neoliberal Thought Collective, 139, 154 (Philip Mirowski & Dieter Plehwe eds., 2009). Hayek had already presaged some of the basic ideological premises of the Chicago School of Antitrust in his book, The Road to Serfdom.11F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944). Hayek famously argued that any interference with a pure laissez-faire economy would thwart the ability of prices to relay the necessary information for the economy to naturally equilibrate.12Fred L. Block, Capitalism: The Future of an Illusion 87 (2018) (“Friedman and his allies consistently exaggerate the effectiveness of markets as information processing machines. The reality is that in most market situations, consumers lack key pieces of information for rational decision making. For example, most people don’t know whether the car actually needs a new muffler or a new transmission when they take it to the mechanic. When they buy a pint of strawberries, they don’t know if the ones on the bottom have already gotten moldy. Even in economic theory, price signals will not optimize the use of resources when consumers are being misled about what they are getting for their dollars. This is precisely why in building economic models, economists frequently posit perfect information.”).

But Hayek’s view was largely just that—a view. Hayek offered no theoretical or empirical justification for his argument.13See, e.g., Hayek, supra note 11, at 91–97. Any subsequent adoption of Hayek’s view solely on faith was deeply misguided. Later microeconomists demonstrated that if equilibrium is disturbed, market price signals do not guarantee a return to equilibrium.14See Andrew S. Caplin & Daniel F. Spulber, Menu Costs and the Neutrality of Money, 102 Q. J. Econ. 703, 714 (1987). Markets under laissez-faire regimes are not stable in any event.15Samuel Bowles, Alan Kirman & Rajiv Sethi, Friedrich Hayek and the Market Algorithm, 31 J. Econ. Persp. 215, 221–23 (2017) (demonstrating no general proof of stability of competitive equilibrium); see also Michael Mandler, Sraffian Indeterminacy in General Equilibrium, 66 Rev. Econ. Stud. 693, 693 (1999); Frank Ackerman, Still Dead After All These Years: Interpreting the Failure of General Equilibrium, 9 J. Econ. Meth. 119, 121–23 (2002). Hayek’s famous argument for unregulated markets was pure conjecture,16Moreover, the notion that political liberties were undermined by government action also appears false. After the publication of The Road to Serfdom, the United States passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the right to vote was lowered from 21 to 18, and the Supreme Court recognized the right to counsel (Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335, 344–45 (1963)), rights to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479, 484–86 (1965), Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113, 155 (1973), overruled by Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 142 S. Ct. 2228, 2284 (2022)), and reaffirmed freedom of the press (N.Y. Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254, 268–69, 292 (1964)). These cases expanded citizen rights and liberties, not reduced them. one that was adopted more as a religion than as having scientific merit.

Nonetheless, the Chicago School followed this religious polestar. What followed was a series of projects (the Free Market Study and the Antitrust Project) with the participation of Edward Levi, John McGee, Ward Bowman, Robert Bork, Richard Posner, and others.17Bruce H. Kobayashi & Timothy J. Muris, Chicago, Post-Chicago, and Beyond: Time to Let Go of the 20th Century, 78 Antitrust L.J. 147, 151, 154 (2012). In their 1956 article, Professors Aaron Director and Edward Levi discussed the emerging views of the Chicago School of economics on antitrust law.18Aaron Director & Edward H. Levi, Law and the Future: Trade Regulation, 51 Nw. U.L. Rev. 281, 281–82 (1956). They plainly stated the Chicago School’s main point: “We believe the conclusions of economics do not justify the application of the antitrust laws in many situations in which the laws are now being applied.”19Id. at 282. The driving force behind the Chicago School’s antitrust policy and its adoption of the Consumer Welfare Standard was open hostility to the broad application of antitrust laws.

Director and Levi asserted that “[t]he [Sherman Act] arose out of an antipathy towards monopoly, and those restraints which were thought to have consequences of monopoly. And it is in the identification and the prediction of the consequences of monopoly that economics has the most to contribute.”20Id. at 287. Thus, according to these authors, only mergers to monopoly and price-fixing cartels were legitimate subjects of antitrust scrutiny. Director and Levi doubted that any single firm could exercise true monopoly power: “It is much less common than it was [earlier in time] to have an industry in which one firm has seventy or more percent control over productive capacity or sales.”21Id. at 284. Abusive conduct such as vertical integration, tying price discrimination, resale price maintenance, and exclusionary conduct should not come under antitrust scrutiny because “economic teaching gives little support to the idea that the abuses create or extend monopoly.”22Id. at 290.

In the meantime, Judge Robert Bork was developing the argument for a normative economic theory that would undermine the traditional goals of antitrust, erode protection of democracy and small business, and circumscribe antitrust enforcement to corporate behavior that decreased output for consumers in the output market. In early articles, Judge Bork described the Consumer Welfare Standard goal as “wealth maximization.” For example, he wrote in the Yale Law Journal in 1965 that “[t]he existing scope and nature of the Sherman Act, as well as considerations of effective administration, thus indicate that the statute is better suited to implement the policy of wealth maximization than the policies underlying the Brandeis approach.”23Robert H. Bork, The Rule of Reason and the Per Se Concept: Price Fixing and Market Division, 74 Yale L. J. 775, 838 (1965).

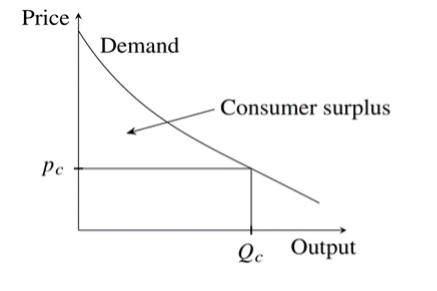

In The Antitrust Paradox, Judge Bork abandoned “wealth maximization” and took a different tack.24Robert H. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox 79 (1978). He repackaged Professor Alfred Marshall’s consumer surplus model as the basis for the Consumer Welfare Standard.25See id. at 90–91, 107–08. He introduced Marshall’s approach in Chapters 4 and 5 of The Antitrust Paradox.26See id. He did so by using a graph based on a standard “Economics 101” understanding of demand and price in a perfectly competitive market:

Figure 1: Consumer Surplus in Perfect Competition27See id. at 107.

The graph illustrates the demand curve for only one person, not the entire market. In Marshall’s approach, the “value” of Qc apples, for example, to this person is the area under his or her demand curve for apples between zero and Qc apples. This represents the amount of money he or she is willing and able to pay for Qc apples—or so it was thought. This area under the demand curve was also thought to be a representation in dollars of the consumer utility from Qc apples, although this is not a completely correct idea either. In return for receiving this value (loosely speaking), the consumer merely must pay the rectangle defined by the uniform competitive price, Pc, times the quantity purchased, Qc. Thus, the consumer’s “value” for Qc apples exceeds his expenditure by an amount called the consumer surplus, which is equal to the area between the demand curve and the uniform competitive price.28Even under this assumption, however, it is not clear that consumer surplus results in greater welfare. For example, suppose the product at issue is cigarettes. Greater consumption of cigarettes due to lower cigarette prices will not likely result in greater human well-being. This point is made by Professor Barak Orbach, who distinguishes between surplus and welfare. Barak Y. Orbach, The Antitrust Consumer Welfare Paradox, 7 J. Comp. L. & Econ. 133, 133, 140, 146–47 (2010). Judge Bork was unclear in his definitions. He sometimes included producer surplus and other times did not. However, economic surplus, which can only be increased by lower prices or higher demand, was the sole goal of the Consumer Welfare Standard and the only criteria for rendering conclusions about corporate strategy under the antitrust laws.29The Post-Chicago School has accepted this approach. At best, they may recognize that in input markets, the “economic rent” accruing to an input supplier is the excess of what an input supplier receives for the input over the minimum payment required to induce him or her to supply that input, and that there are several different types of “surplus,” generated in both output and input markets. Beth Stratford, Rival Definitions of Economic Rent: Historical Origins and Normative Implications, New Pol. Econ. 1, 8 (2022). But they do not stray from the Chicago School’s focus on economic surplus, and they reject the traditional antitrust goals that do not impact short-run economic surplus. See Yoo, supra note 1, at 2152.

With the Consumer Welfare Standard as the normative standard, the Chicago School created a positive economic antitrust policy program wherein the only legitimate goal of antitrust enforcement is to prevent price increases that result from excessive market power. Here, we provide a few examples of the Chicago School policy:

(1) Horizontal Conspiracies. The Chicago School contended that horizontal conspiracies did not require significant enforcement resources because they believed cartels to be unstable with a tendency to self-destruct because of the strong incentive to cheat.30See George J. Stigler, A Theory of Oligopoly, 72 J. Pol. Econ. 44, 46 (1964).

(2) Mergers. In the Chicago School’s view, mergers, particularly mergers that are not to monopoly, are usually efficiency-increasing and undertaken for that purpose.31See Frank H. Easterbrook, Limits of Antitrust, 63 Tex. L. Rev. 1, 2–4 (1984); Bork, supra note 24, at 221.

(3) Predatory Pricing. The Chicago School argued that predatory pricing is an irrational business strategy because the predator loses money during the predation stage, and “if he tries to recoup it later by raising his price, new entrants will be attracted.”32Richard A. Posner, The Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis, 127 U. Pa. L. Rev. 925, 927 (1979).

(4) Tying Arrangements. Only under very specific conditions does a tying arrangement raise antitrust concerns for the Chicago School.33A tie only presents a problem when there is a regulatory constraint on the price of the tying product. See Bork, supra note 24, at 376. The logic is that firms face a reservation price on the bundle of tied goods and have the option of raising the price of the tying product in order to obtain any available rents. Consequently, tying is not a profitable strategy unless it results in efficiencies.34See id. at 372–81; Richard A. Posner, Antitrust Law: An Economic Perspective 171–84 (1976).

(5) Resale price maintenance. Resale price maintenance and non-price vertical restraints are also efficiency-producing because they are necessary for the provision of presale dealer services.35See Ward S. Bowman, Jr., Resale Price Maintenance¾A Monopoly Problem, 25 J. Bus. U. Chi. 141, 152–53 (1952); Lester G. Telser, Why Should Manufacturers Want Fair Trade?, 3 J.L & Econ. 86, 96–98 (1960); Richard A. Posner, The Rule of Reason and the Economic Approach: Reflections on the Sylvania Decision, 45 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1, 4 (1977).

(6) Vertical Integration. Nor does vertical integration present an antitrust concern. The concern raised by a vertical merger is foreclosure, or the inability of a competitor to gain access to vendors or distributors. According to the Chicago School, this scenario would not happen. Vertical mergers merely realigned trading parties and do not cause foreclosure.36Robert H. Bork, Vertical Integration and the Sherman Act: The Legal History of an Economic Misconception, 22 U. Chi. L. Rev. 157, 198–200 (1954); see Bork, supra note 24, at 228. Moreover, vertical integration usually involves efficiencies such as the elimination of the double marginalization problem and the elimination of transaction costs from contracting.37See Dennis W. Carlton & Jeffrey M. Perloff, Modern Industrial Organization 501–20 (1994).

Thus, an antitrust student taking an exam from a law professor who adopted a Chicago School perspective would have an exam answer that sought little to no antitrust enforcement. Indeed, under the theory, little to no antitrust enforcement was warranted. The Chicago School maintained that big business seeks efficiencies, which benefit the economy as a whole, and the previous antitrust policy that had governed the previous eighty years or so had been harmful and unwarranted.

2. Influence

The Chicago School’s blend of “science of economics” with appealing normative policy prescriptions that appeared scientific rapidly took over antitrust law.38The Chicago School received substantial and sustained funding to support the effort to create such influence in the courts and administration. See Darren Bush & Marck Glick, The “Conspiracy” of Consumer Welfare Theory, ProMarket (Aug. 12, 2022), https://perma.cc/Z9FA-ZEXY. . In a recent paper, Professors Filippo Lancieri, Eric Posner, and Luigi Zingales analyze the changes in antitrust enforcement that occurred after the rise of the Chicago School. They find that “no matter where one looks, the overall downward trend in public civil enforcement of the antitrust laws is unmistakable, in particular when targeting dominant companies that monopolize or attempt to monopolize markets.”39Filippo Lancieri, Eric A. Posner & Luigi Zingales, The Political Economy of the Decline of Antitrust Enforcement in the United States 7 (Becker Friedman Inst., Working Paper No. 2022-104, 2022).. In line with the Chicago School, “enforcement [focused on] cartels and mergers that create (near) monopolies.”40Id. Curiously, this sentence was deleted in an updated draft of the piece. See Filippo Lancieri, Eric A. Posner & Luigi Zingales, The Political Economy of the Decline of Antitrust Enforcement in the United States (Mar. 20, 2023), https://perma.cc/MEA6-Z2C9.

The Chicago School had a strong influence on the Supreme Court doctrine on antitrust. The first significant Chicago School antitrust success at the Supreme Court was Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc.41433 U.S. 36 (1977). There, Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the 6-2 majority, held that non-price vertical restraints warrant only rule-of-reason analysis.42Id. at 37, 58–59. Powell authored a famous 1971 memo, sent to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and titled “Attack on American Free Enterprise System,” which “is widely cited as the beginning of the corporate mobilization to transform American law and politics.” Nancy MacLean, Democracy in Chains: The Deep History of the Radical Right’s Stealth Plan for America 125 (2017). As a result, vertical exclusive customer and territory restrictions became very difficult to challenge. The standard for proving vertical conspiracies was also elevated in Monsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Service Corp.,43465 U.S. 752, 764, 768 (1984). and the per se rule against resale price maintenance slowly eroded away until it was finally eliminated in Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, Inc.,44551 U.S. 877, 881–82, 900 (2007). a rare direct reversal of 100-year-old precedent.

In the late 1970s and the 1980s, the Court began to carve out exceptions to the per se rule against horizontal price fixing. The GTE Sylvania decision signaled that a “demanding standard[]” should be applied before the per se rule should be applied.45Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., 433 U.S. 36, 50 (1977); see also FTC v. Ind. Fed’n of Dentists, 476 U.S. 447, 458–59 (1986) (“we have been slow . . . to extend per se analysis to restraints imposed in the context of business relationships where the economic impact of certain practices is not immediately obvious . . . .”). In Broadcast Music, Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc.,46441 U.S. 1 (1979). the Court carved out the exception for situations where horizontal coordination was plausibly needed to offer a new product, specifically a blanket license.47Id. at 22–23. In NCAA v. Board of Regents of University of Oklahoma,48468 U.S. 85 (1984). the Court held the NCAA came within the new product exception to the per se rule.49Id. at 115–17, 117 n.60.

We do not mean to suggest that Broadcast Music and Board of Regents were purely the result of the influence of the Chicago School. While the Chicago School contended that cartels were unstable and less worrisome than earlier thought, there were legitimate limits to the application of the United States v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co.50310 U.S. 150 (1940). approach of a broad per se rule for horizontal conspiracies. For instance, integrated entities, like firms and partnerships, could not reasonably be subject to the per se rule. The Chicago School swayed the courts, however, to make exceptions even for more loosely integrated structures like the NCAA.51Indeed, the Supreme Court cited to Robert Bork’s The Antitrust Paradox in noting that “[S]ome activities can only be carried out jointly. Perhaps the leading example is league sports. When a league of professional lacrosse teams is formed, it would be pointless to declare their cooperation illegal on the ground that there are no other professional lacrosse teams.” Board of Regents, 468 U.S. at 101 (alteration in original) (quoting Bork, supra note 24, at 278). The Chicago School’s skepticism about cartel stability also contributed to the higher burden that emerged for proof of conspiracy in Matsushita Electric Industrial Co. v. Zenith Radio Corp.52475 U.S. 574, 586–87 (1986). and Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly.53550 U.S. 544, 564–66 (2007).

The Chicago School’s influence also led to a more permissive approach to mergers. In United States v. General Dynamics Corp.,54415 U.S. 486 (1974). the Court rejected the Department of Justice’s (“DOJ’s”) reliance on market shares, challenging the assumption that they reflected future competitive significance.55Id. at 510–11. Extending the departure from earlier precedent, lower courts also engineered several defenses to a merger challenge. In United States v. Syufy Enterprises,56903 F.2d 659 (9th Cir. 1990). the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit allowed a merger with high market shares because of evidence of easy entry.57Id. at 666–67, 671. So did the Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit in United States v. Baker Hughes Inc.58908 F.2d 981, 985 (D.C. Cir. 1990). Then, in Federal Trade Commission v. University Health, Inc.,59938 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1991). the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit held that evidence of substantial efficiencies can be used to rebut evidence of higher concentration.60Id. at 1222–24.

The Chicago School’s views, despite being strongly against enforcement, soon crept their way into enforcement agency pronouncements. Since 1982, the various versions of the Horizontal Merger Guidelines published by the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) weakened earlier agency merger enforcement.61Guidelines were issued by the Department of Justice (“DOJ”) in 1982 and 1984 and by the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) in 1982. U.S. Dep’t of Just., Merger Guidelines (1982), reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) ¶ 13,102; U.S. Dep’t of Just., Merger Guidelines (1984), reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) 13,103; Fed. Trade Comm’n, Statement of the Federal Trade Commission Concerning Horizontal Mergers (1982), reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) ¶ 13,200. In 1992 the FTC and the DOJ jointly issued Horizontal Merger Guidelines. U.S. Dep’t of Just. & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Merger Guidelines (1992), reprinted in 4 Trade Reg. Rep. (CCH) ¶ 13,104. These were revised in 1997 (regarding efficiencies) and then again in 2010. U.S. Dep’t of Just. & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Merger Guidelines (rev. ed. 1997), https://perma.cc/LDD8-UQSP; U.S. Dep’t of Just. & Fed. Trade Comm’n, Merger Guidelines (rev. ed. 2010) [hereinafter 2010 Merger Guidelines], https://perma.cc/UNT8-P4Z7. The 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines require much more than the original structural presumptions mandated by the Court in the Brown Shoe Co. v. United States62370 U.S. 294, 334–46 (1962) (holding that the Clayton Act prohibited the merger of a shoe manufacturer and a shoe seller because of their market positions). and United States v. Philadelphia National Bank63374 U.S. 321, 365–72 (1963) (holding that the Clayton Act prohibited the merger of two banks because of their market positions). cases. Instead, the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines require that the agencies develop and prove an anticompetitive scenario that would likely result from the proposed merger.64See 2010 Merger Guidelines, supra note 61, at 30. Even if that exacting hurdle is met, a showing of easy entry or possibly significant efficiencies can still defeat the case for the merger challenge. Moreover, despite prior Chicago School arguments that market concentration was temporary, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) thresholds were increased, with “highly concentrated markets” starting at an HHI of 2500 (previously 1800).65Theo Francis & Ryan Knutson, Wave of Megadeals Tests Antitrust Limits in U.S., Wall Street Journal (Oct. 18, 2015, 10:55 PM), https://perma.cc/2SRJ-YY5R. As of this writing, the much-anticipated 2023 Guidelines have not been published. They may or may not continue this trend. See generally 2010 Merger Guidelines, supra note 61. Regardless, the antitrust enforcement agencies adopted a theory hindering themselves, with predictable results. This was true regardless of the politics of any given administration or who controlled Congress.

Finally, the Chicago School completely eviscerated any FTC or DOJ interest in enforcing the Robinson-Patman Act despite the fact that both Congress and the courts have resisted the wholesale abandonment of that law.66Harry Ballan, The Courts’ Assault on the Robinson-Patman Act, 92 Colum. L. Rev. 634, 645–48 (1992) (noting that the Robinson-Patman Act has not been repealed by Congress and has been kept on life support through judicial intervention). While the Robinson-Patman Act is still viable, the courts have whittled away at the FTC v. Morton Salt67334 U.S. 37, 45 (1948) (“We think that the language of the Act, and the legislative history just cited, show that Congress meant by using the words ‘discrimination in price’ in § 2 that in a case involving competitive injury between a seller’s customers the Commission need only prove that a seller had charged one purchaser a higher price for like goods than he had charged one or more of the purchaser’s competitors.”). inference, making the burden of meeting the cost-justification defense lighter while rendering the element of competitive injury (and antitrust injury for private plaintiffs) much more difficult.

In sum, the Chicago School’s influence has extended not only to the courts but also to the very antitrust enforcement agencies that should seek to enforce the antitrust laws. The enforcement agencies’ adoption of a theory that is, by all measures, anti-enforcement seems to be strikingly masochistic.

3. Mispredictions

Judge Frank Easterbrook famously argued that even if the Chicago School approach is too permissive, the impacts should be minimal:

For a number of reasons, errors on the side of excusing questionable practices are preferable. First, because most forms of cooperation are beneficial, excusing a particular practice about which we are ill informed is unlikely to be harmful. . . . Second, the economic system corrects monopoly more readily than it corrects judicial errors. . . . Third, in many cases the costs of monopoly wrongly permitted are small, while the costs of competition wrongly condemned are large.68Easterbrook, supra note 31, at 15–16.

None of Easterbrook’s assumptions, however, necessarily follow from the Consumer Welfare Standard. They appear to have been taken on faith, much like the Consumer Welfare Standard itself.

Worse, his assumptions have proven factually false. Coordinated practices are more widespread than Easterbrook claims.69See generally Margaret C. Levenstein & Valerie Y. Suslow, What Determines Cartel Success?, 44 J. Econ. Lit. 43, 43 (2006) (examining empirical studies of cartels and finding that extended collusion between firms can be successful). The average cartel in the studies reviewed by Professors Margaret Levenstein and Valerie Suslow survived 3.7 to 10 years,70Id. at 50. and historically, some cartels endured for more than fifty years.71Id. at 53. Using a more current example, there is no sign of market forces undermining the monopoly power of the tech platforms.72See Marshall Steinbaum, Eric Harris Bernstein, & John Sturm, Powerless: How Lax Antitrust and Concentrated Market Power Rig the Economy Against American Workers, Consumers, and Communities, Roosevelt Inst. 8, 39–40 (Feb. 2018); Too Much of a Good Thing, Economist (Mar. 26, 2016), https://perma.cc/Z3Y9-RAKA. Thus, the myth of transience of monopoly power strongly endures its empirically disprovable assertions.

There has been an enormous outpouring of analysis and data questioning the effectiveness of antitrust enforcement under the sway of Chicago School principles. This literature is broad in nature, including the popular press,73See Francis & Knutson, supra note 65; Too Much of a Good Thing, supra note 72; Stacy Mitchell, The Rise and Fall of the Word ‘Monopoly’ in American Life, Atlantic (July 20, 2017), https://perma.cc/A42B-TZ6P; see also Carl Shapiro, Antitrust in a Time of Populism, 61 Int. J. Ind. Org. 714, 717–19 (2018) (cataloging media coverage of the increasing concentration of the American economy). economics journals,74See Gustavo Grullon, Yelena Larkin & Roni Michaely, Are US Industries Becoming More Concentrated?, 2019 Rev. Fin. 697, 734–35; Germán Gutiérrez & Thomas Philippon, Declining Competition and Investment in the U.S., 54 (Nat’l Bureau Econ. Rsch., Working Paper No. 23583, 2017). See generally David Autor, David Dorn, Lawrence F. Katz, Christina Patterson & John Van Reenen, Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share, 107 Amer. Econ. Rev. 180, 185 (2017) (noting the increasing concentration of the American economy). policy institute papers,75See Jonathan B. Baker, Market Power in the U.S. Economy Today, Wash. Ctr. Econ. Growth 1 (Mar. 2017), https://perma.cc/NZM2-LZ8Q; Marc Jarsulic, Ethan Gurwitz, Kate Bahn & Andy Green, Reviving Antitrust, Ctr. Amer. Progress 2 (June 2016), https://perma.cc/ZQ44-YUU6; Jay Shambaugh, Ryan Nunn, Audrey Breitwieser & Patrick Liu, The State of Competition and Dynamism: Facts About Concentration, Start-Ups, and Related Policies, Hamilton Project 16–18 (June 2018), https://perma.cc/4U5Y-E745; Steinbaum et al., supra note 72, at 16–17; Marshall Steinbaum & Maurice E. Stucke, The Effective Competition Standard, Roosevelt Inst. 1 (Sept. 2018), https://perma.cc/E323-QKS5. and law reviews.76See Daniel A. Crane, Antitrust’s Unconventional Politics, 104 Va. L. Rev. Online 118, 119 (2018), https://perma.cc/6U4X-GGLV; Lina M. Khan, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 Yale L.J. 710, 804 (2017); Sandeep Vaheesan, The Twilight of the Technocrats’ Monopoly on Antitrust?, 127 Yale L.J.F. 980, 995, https://perma.cc/QK7R-8JA9. The literature indicates a consensus that market concentration in the United States has grown significantly since the 1990s. Again, we recognize in the changed 2010 merger guidelines threshold of “highly concentrated” as an implicit recognition of increasing market concentration.77See 2010 Merger Guidelines, supra note 61, at 19.

Rising concentration, however, does not conclusively demonstrate an increase in market power because national concentration data assumes national geographic markets and product categories that may not be coextensive with product markets. Nonetheless, concentration does show that big business has grown in size.78See generally Shapiro, supra note 73; Int’l Monetary Fund, The Rise of Corporate Market Power and its Macroeconomic Effects, World Economic Outlook (Apr. 2019), https://perma.cc/CD6E-EWN3. In addition, anecdotal evidence suggests that market power has increased. As a representative sample of this literature, Jonathan Tepper and Denise Hearn observed that today just three companies control the nation’s cable market.79Jonathan Tepper & Denise Hearn, The Myth of Capitalism: Monopolies and the Death of Competition 116–17 (2019). Microsoft still has a 90% share of computer operating systems.80Id. at 117. Facebook has 75% of the global social media market,81Id. and Google has 90% of search advertising.82Id. at 118. Moreover, a small number of big firms control many industries: milk, modified seed, microprocessors, airlines, health insurance, medical care, group purchasing organizations, drugs, meat and poultry, agriculture, media, title insurance, and other industries.83Id. at 118–37. The economic effects of market power are dramatic. Professor Thomas Philippon estimates the costs of increased market power in the U.S. economy at about $1 trillion per year because of lower investment and lower productivity.84Thomas Philippon, The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets 293 (2019).

Another major result of lax antitrust enforcement is that the mark-ups, and therefore profit margins, of these large firms have increased. For example, in their widely-cited National Bureau of Economic Research paper, Professors Jan De Loecker and Jan Eeckhout found that firm-level markups have increased from 21% to 61% since 1980.85Jan De Loecker, Jan Eeckhout & Gabriel Unger, The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications, 135 Q.J. Econ. 561, 561 (2020). Numerous studies have come to similar conclusions.86Jarsulic et al., supra note 75, at 5 (demonstrating that after-tax corporate profits have risen since 2000); Gauti Eggertsson, Jacob A. Robbins & Ella Getz Wold, Kaldor and Piketty’s Facts: The Rise of Monopoly Power in the United States 4 (Wash. Ctr. for Equitable Growth, Working Paper, 2018) (showing “a large increase in markups over the past forty years”); Shapiro, supra note 73, at 733 (“[T]hese data strongly suggest that U.S. corporations really are systematically earning far higher profits than they were 25 or 30 years ago.”). Many factors influence profits, and market power can be a key influence. Market power can cause differential profits between firms. Market power in consumer goods industries can lower real wages and can increase profits system-wide.87In the history of the economics field, this is known as the theory of profit on alienation. System wide, if every firm raises the mark up, what one firm gains as a seller it loses as a buyer. The exception is if workers cannot raise money wages then their real wage declines and this could result in higher profits system wide.

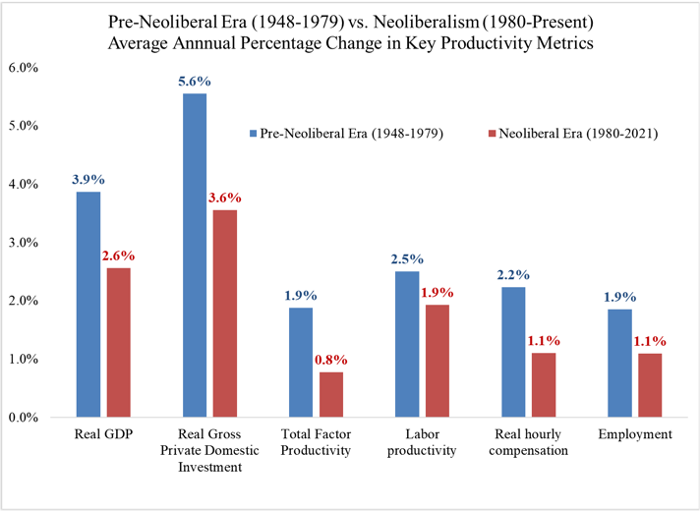

The Chicago School held out the promise that by unleashing business from regulation and antitrust scrutiny, the economy would thrive. There would be more growth, higher productivity, and, eventually, more for everyone. This has patently not occurred. Figure 2 compares the major key macroeconomic indicators of economic prosperity for two periods. The first we refer to as the “pre-Neoliberal Era” for the period after World War II but before the “Neoliberal” revolution initiated under the Reagan administration.

Figure 2: Comparing Key Productivity Metrics During the Pre-Neoliberal and Neoliberalism Eras88Rates of change calculated by incorporating base year from previous periods (1947 and 1979, respectively). No data is available with respect to total factor productivity for 1947 and 1948. No data is available for 1947 for real hourly compensation and employment. The year 2022 represents the most recent data available. All data on file with authors. See Real Gross Domestic Product, Fed. Rsrv. Bank St. Louis (May 25, 2023), https://perma.cc/G8K8-6YVL (selecting “DOWNLOAD” to access raw data); Real Gross Private Domestic Investment, Fed. Rsrv. Bank St. Louis (May 25, 2023), https://perma.cc/T6K7-MC6W (selecting “DOWNLOAD” to access raw data); Productivity: Historical Productivity and Costs Measures, U.S. Bureau Lab. Stat. (Mar. 23, 2023), https://perma.cc/5USP-5N3R (downloading data from “Historical total factor productivity measures (SIC 1948-87 linked to NAICS 1987-present)”); Productivity: Labor Productivity and Costs Measures, U.S. Bureau Lab. Stat. (June 1, 2023), https://perma.cc/5USP-5N3R (downloading data from “Major sectors: nonfarm business, business, nonfinancial corporate, and manufacturing”).

The pre-Neoliberal era (i.e., the pre-Chicago School period) was far more prosperous than after the rise of the Chicago School. Antitrust policy is not the only reason for the economic decline, but it does indicate that the casual empiricism does not support the promises of the Chicago School.89The reasons for this decline are discussed in Part III of this paper.

B. The Post-Chicago School Criticism and Its Influence

Beginning in the 1990s, a group of more centrist economists engaged in theoretical and empirical industrial organization analysis took issue with many of the key premises of the Chicago School. Their conclusions have made major contributions to the positive economic analysis of antitrust and are embraced by the New Brandeisians. For example, as Professor Tim Wu described in his recent book:

The Chicago movement, unsurprisingly, began to encounter major resistance during the 1980s through the 2000s. A group of economists and other academics, styled the “post-Chicago” school, emerged to challenge many of its basic premises. What the post-Chicago academics demonstrated was this: Even if you took a strictly economic view of the antitrust laws, you didn’t actually reach Bork’s conclusions.90Tim Wu, The Curse of Bigness: Antitrust in the New Gilded Age 107 (2018).

The Post-Chicago School undermined the majority of the original Chicago School policy prescriptions. We detail the differences with the categories from the preceding section:

(1) Horizontal Conspiracies. In contrast to the Chicago School theory, Post-Chicago economists have shown that cartels can be stable.91The “Folk Theorem” shows that in an infinitely repeated game, a cartel can be a subgame perfect Nash equilibrium. This means that it can be fully stable. See Jean Tirole, The Theory of Industrial Organization § 6.3 (1988); Jonathan B. Baker, Recent Developments in Economics that Challenge Chicago School Views, 58 Antitrust L.J. 645, 649–50 (1989). Entry barriers can exist and can slow or deter entry into uncompetitive markets.92See Steven C. Salop, Measuring Ease of Entry, 31 Antitrust Bull. 551, 556–57, 561–62 (1986) (stressing the role of minimum efficient scale and sunk costs).

(2) Mergers. Post-Chicago commentators also are less sanguine about merger efficiencies. Like the Chicago School, however, they continue to believe that efficiencies are a relevant factor in merger analysis.93Jonathan B. Baker & Carl Shapiro, Reinvigorating Horizontal Merger Enforcement, in How the Chicago School Overshot the Mark: The Effect of Conservative Economic Analysis on U.S. Antitrust 256 (Robert Pitofsky ed., 2008).

(3) Predatory Pricing. Post-Chicago analysis has shown that predatory pricing can be a rational and successful business strategy.94First, victims may not be able to obtain finance during the predation stage because capital markets are not entirely efficient. A bank manager may not know, for example, whether the victim’s low profits are due to predation or bad management, and there may not be a credible way for the victim to signal good management to the bank. Second, predation against several rivals can create a reputation for irrational aggressiveness that can deter entry or cause potential victims in other markets to cooperate. Thus, recoupment can occur in markets other than where the predation occurred. See Paul Migrom & John Roberts, Predation, Reputation, and Entry Deterrence, 27 J. Econ Theory 280, 281, 302–03 (1982); Jonathan B. Baker, Predatory Pricing After Brooke Group: An Economic Perspective, 62 Antitrust L.J. 585, 589–91, 591 n.27 (1994).

(4) Tying Arrangements. Post-Chicago analysis has shown that tying arrangements can harm competition by raising barriers to entry.95Barry Nalebuff, Bundling as an Entry Barrier, 119 Q.J. Econ. 159, 162–63, 173 (2004) (showing that tying can control entry and modeling a bundling strategy in which the gains from entry deterrence are much greater than the gains from price discrimination). Certain bundling strategies can also increase total profits by reducing competition in the tied market.96Michael D. Whinston, Tying, Foreclosure, and Exclusion, 80 Am. Econ. Rev. 837, 844 (1990); Barry Nalebuff, Bundling as a Way to Leverage Monopoly 17, 23–24 (Yale Sch. Mgmt., Working Paper No. 36, 2004). The analysis of tying and bundling by Professor Einer Elhauge illuminates the basic problem with Chicago School economics, advancing a special case as universal and therefore justifying a conservative legal rule.97See Einer Elhauge, Tying, Bundled Discounts, and the Death of the Single Monopoly Profit Theory, 123 Harv. L. Rev. 397, 399–400 (2009). For example, the Chicago School argued that a firm with monopoly power in one market cannot increase its monopoly profits by tying or leveraging itself in a second market.98Posner, supra note 34, at 197–99. This meant that claims about illegal tying were irrational, absent some special limitation on raising prices in the tying market, such as a regulatory cap. But Elhauge demonstrates that this conclusion only holds when several key assumptions are present: (1) fixed usage of the tied product, (2) correlated demand for the products, (3) fixed usage of the tying product, (4) the tie can’t impact competitiveness in the tying market, and (5) fixed competitiveness in the tied market.99Elhauge, supra note 97, at 399–400. These assumptions are very often not present, so the Chicago School’s skepticism about tying and leveraging is not strongly undergirded.

(5) Resale Price Maintenance. Some Post-Chicago economists have further challenged the core Chicago School analysis of resale price maintenance.100However, cases where resale price maintenance does not increase efficiency are possible. See F.M. Scherer, The Economics of Vertical Restraints, 52 Antitrust L.J. 687, 691–92, 697–98, 704 (1983); Robert L. Steiner, Vertical Restraints and Economic Efficiency 4, 24 (Fed. Trade Comm’n, Working Paper No. 66, 1982). Many cases of resale price maintenance do not involve pre-sale services. See Sharon Oster, Levi Strauss, 19 J. Reprints Antitrust L. & Econ. 47, 55 (1989); Robert Pitofsky, Are Retailers Who Offer Discounts Really “Knaves”?: The Coming Challenge to the Dr. Miles Rule, 21 Antitrust 61, 63 (2007). But other Post-Chicago economists have also offered alternative theories, not based on post-sale service, to justify resale price maintenance.101See Howard P. Marvel & Stephen McCafferty, Resale Price Maintenance and Quality Certification, 15 Rand J. Econ. 346, 358–59 (1985); Roger D. Blair & David L. Kaserman, Antitrust Economics 377–81 (2009). However, little empirical evidence exists to justify any of these theories, and if some consumers desire these benefits while others do not, the overall impact can be ambiguous. See William S. Comanor, Vertical Price-Fixing, Vertical Market Restrictions, and the New Antitrust Policy, 98 Harv. L. Rev. 983, 991–92, 999 (1985); Benjamin Klein, Competitive Resale Price Maintenance in the Absence of Free-Riding, 76 Antitrust L.J. 431, 433–34 (2009). Professor Warren Grimes argued that Resale Price Maintenance can harm consumers in two ways: (1) by maintaining high manufacturer margins and (2) by promoting premium brands that are not superior products. Warren S. Grimes, A Dynamic Analysis of Resale Price Maintenance: Inefficient Brand Promotion, Higher Margins, Distorted Choices, and Retarded Retailer Innovation, 55 Antitrust Bull. 101, 115–16 (2010).

(6) Vertical Integration. Several economists have shown that profitable vertical integration can cause foreclosure.102See Michael A. Salinger, Vertical Mergers and Market Foreclosure, 103 Q.J. Econ. 345, 354–55 (1988); see generally Steven C. Salop, Invigorating Vertical Merger Enforcement, 127 Yale L.J. 1962, 1966 n.17 (2018) (listing relevant sources). Vertical integration can also harm competition.103Non-integrated firms may face distributors with augmented market power or higher costs. This can lead to higher prices, which allow the vertically integrated producer to raise its prices. See Thomas G. Krattenmaker and Steven C. Salop, Anticompetitive Exclusion: Raising Rivals’ Costs to Achieve Power Over Price, 96 Yale L. J. 209, 238–43 (1986); Baker, supra note 91, at 647. Finally, it has been demonstrated that there are limitations to achieving efficiencies from eliminating double marginalization.104Salop, supra note 102, at 1970–71.

The Post-Chicago economists have had influence with the antitrust agencies, in part because they advocated stronger antitrust enforcement.105See Steven C. Salop, Modifying Merger Consent Decrees to Improve Merger Enforcement Policy, Antitrust, Fall 2016, at 15, 17, 19; Jonathan B. Baker, The Case for Antitrust Enforcement, 17 J. Econ. Persp. 27, 27–32, 45–46 (2003). But courts have been stubbornly resistant to abandoning Chicago School principles. For example, in Verizon Communications, Inc. v. Law Offices of Curtis V. Trinko,106540 U.S. 398 (2004). the Supreme Court stated, “the opportunity to charge monopoly prices—at least for a short period—is what attracts ‘business acumen’” and leads to “innovation and economic growth.”107Id. at 407. There is little empirical evidence to support this supposition. The Court’s opinion is merely Chicago School conjecture.108Maurice E. Stucke, Should we be Concerned About Data-Opolies?, 2 Geo. L. Tech. Rev. 275, 303–04 (2018).

In Brooke Group Ltd v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp.,109509 U.S. 209 (1993). the Supreme Court heightened the burden for demonstrating predatory pricing while ignoring the Post-Chicago School theories of recoupment.110See id. at 225–26; Baker, supra note 94, at 585–86. In Leegin, the Supreme Court overturned one hundred years of precedent to hold that resale price maintenance was no longer per se illegal and that the rule of reason would apply.111Leegin Creative Leather Products v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U.S. 877, 881–82, 900 (2007). The majority opinion largely recounted the Chicago School claims about the efficiencies that can be derived from controlling free riders in retail using resale price maintenance. In his dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer identified the weakness in the Chicago School argument. He asked, “How often, for example, will the benefits to which the Court points occur in practice? I can find no economic consensus on this point. . . . All this is to say that the ultimate question is not whether, but how much, ‘free riding’ of this sort takes place.” Id. at 915–16 (Breyer, J., dissenting). The majority accepted the Chicago School presumptions without factual confirmation and sampled literature only from Chicago School orthodoxy.112See id. at 889 (citing amicus briefs containing “procompetitive justifications for a manufacturer’s use of resale price maintenance”). The only case in which the Post-Chicago School analysis arguably prevailed over the Chicago School at the Supreme Court appears to be Eastman Kodak Co. v. Image Technical Services, Inc.113504 U.S. 451 (1992). In that case, the Court rejected Kodak’s proposition that as a matter of law competition in the equipment market for copy machines would protect Kodak’s installed base from all possible exploitation by Kodak. The Court rejected the presumption stating that “[l]egal presumptions that rest on formalistic distinctions rather than actual market realities are generally disfavored in antitrust law.” Id. at 466–67.

Thus, the Post-Chicago School attempted to move the needle back away from the constrictive antitrust policies adopted along with the Consumer Welfare Theory. It made modest strides in its efforts.

II. The New Brandeisian Approach to Economics and Antitrust

The New Brandeisians reject several of the basic premises of the economic analysis of the Chicago School and the Post-Chicago School. Specifically, they repudiate the Consumer Welfare Standard, they wish to restore antitrust’s traditional social goals, and they offer new policy objectives for antitrust. These issues will be addressed in the next section. Finally, they dismiss the economic method of taking markets as primary and natural and then turning to government action only when a “market failure” is present.114Richard O. Zerbe Jr. & Howard E. McCurdy, The Failure of Market Failure, 18 J. Pol’y Analysis & Mgmt. 558, 559 (1999).

Perhaps the starkest contrast between the Chicago and Post-Chicago Schools and the New Brandeisians is the New Brandeisian recognition that free markets are not naturally occurring.115See Bernard E. Harcourt, The Illusion of Free Markets: Punishment and the Myth of Natural Order 17, 47–48 (2011). For the New Brandeisians, like the early institutional economists and the legal realists, markets are not independent and primary.116See id. The term “free markets” is ideological, not definitional, because no market is truly free of regulation. Indeed, some markets, such as those for wholesale or retail electricity, only exist because of regulation. Nor are markets analytically “free” prior to government or other social organization. Markets cannot exist without secure property rights, contract rules, and criminal sanctions.117Joseph E. Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future 72 (2012) (“The most important role of government, however, is setting the basic rules of the game, through laws such as those that encourage or discourage unionization, corporate governance laws that determine the discretion of management, and competition laws that should limit the extent of monopoly rents. As we have already noted, almost every law has distributive consequences, with some groups benefiting, typically at the expense of others. And these distributive consequences are often the most important effects of the policy or program.”) (citations omitted)); Jules L. Coleman, Risks and Wrongs 61 (1992) (“Competition presupposes a stable, enforceable scheme of property rights. Any such scheme is a collective or public good.”); see generally Betty Mensch, Freedom of Contract as Ideology, 33 Stan. L. Rev. 753 (1981) (reviewing P.S. Atiyah, The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract) (supporting the idea that every market transaction requires contract enforcement, which must be coercive, to protect expectational interests and, further, that voluntary exchange presupposes a world of collective external contract rules and enforcement). Nor can markets exist without social norms for cooperation.118Stiglitz, supra note 117, at 121 (“Cooperation and trust are important in every sphere of society. We often underestimate the role of trust in making our economy work or the importance of the social contract that binds us together. If every business contract had to be enforced by one party’s taking the other to court, our economy, and not just our politics, would be in gridlock. The legal system enforces certain aspects of ‘good behavior,’ but most good behavior is voluntary. Our system couldn’t function otherwise. If we littered every time we could get away with it, our streets would be filthy, or we would have to spend an inordinate amount on policing to keep them clean. If individuals cheated on every contract—so long as they could get away with it—life would be unpleasant and economic dealings would be fractious. Throughout history the economies that have flourished are those where a man’s word is his honor, where a handshake is a deal.”); Samuel Bowles, The Moral Economy: Why Good Incentives are no Substitute for Good Citizens 2–3 (2016) (“I show that these and other policies advocated as necessary to the functioning of a market economy may also promote self-interest and undermine the means by which a society sustains a robust civic culture of cooperative and generous citizens. They may even compromise the social norms essential to the workings of markets themselves. Included among the cultural casualties of this so-called crowding-out process are such workaday virtues as truthfully reporting one’s assets and liabilities when seeking a loan, keeping one’s word, and working hard even when nobody is looking. Markets and other economic institutions do not work well where these and other norms are absent or compromised.”); Block, supra note 12, at 89, 91 (“This dependence of the market system on the rejection of unbridled greed and selfishness has been understood by social theorists back to Adam Smith. . . . Smith’s recognition that a market economy depends on anti-market values was replicated by such key sociological thinkers as Émile Durkheim and Max Weber.”). However, these are only the most fundamental of regulatory requirements.119Jacob S. Hacker & Paul Pierson, Winner-Take-All Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer—And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class 55 (2010) (“The intertwining of government and markets is nothing new. The frontier was settled because government granted land to the pioneers, killed, drove off, or rounded up Native Americans, created private monopolies to forge a nationwide transportation and industrial network, and linked the land settled with the world’s largest postal system.”). The existence of corporations, limited liability, financial markets, credit, currency, unions, work rules, and many other prerequisites of modern markets require detailed legal regimes. As Professor Bernard Harcourt describes,

The fundamental problem is that foundational categories of, on the one hand, “market efficiency” or “free markets,” and on the other hand, “excessive regulation,” “governmental inefficiency,” or “discipline,” are illusory and misleading categories that fail to capture the irreducibly individual phenomena of different forms of market organization. In all markets, the state is present.120Harcourt, supra note 115, at 47.

Thus, there are no “free markets” and “non-free markets.” There are many diverse market organizations depending on how the law and governmental regulatory structures shape these markets. For example, in a recent book, Professor Katharina Pistor shows how contract, property rights, collateral, trust, corporate, and bankruptcy law “can be used to give the holders of some assets a comparative advantage over others.”121Katharina Pistor, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality, at x (2019). She demonstrates how the struggle over how the law is “coded” determines both how wealth is created in markets and how wealth is distributed between asset holders, which determines inequality.122Id.

Perhaps it is this presumption that markets function well that has been the stumbling block of the Chicago and Post-Chicago Schools. That presumption is only advisable if the market itself cannot cure the defect. New Brandeisians recognize that all markets require some government intervention or oversight to function. Chicago and Post-Chicago Schools have ideological blinders to such recognition that markets must have “rules of the game.”

A. Welfare Economics Favors the New Brandeisians

Both the Chicago School and the Post-Chicago School of Antitrust accept the Consumer Welfare Standard as the normative basis for establishing antitrust goals and policies. Both, therefore, are seriously out of step with modern welfare economics. The Consumer Welfare Standard is a simplified version of Marshall and Professor Arthur Pigou’s consumer surplus approach to economic welfare.

There are strong reasons why both are wrong on the economics and why the New Brandeisians are better versed in modern economics. First, modern welfare economics has long ago eschewed the Consumer Welfare Standard and other surplus approaches to economic welfare. Second, the modern application of Consumer Welfare Theory contradicts the limitations even its own founders warned against. Third, Consumer Welfare Theory is deeply and irretrievably flawed and internally inconsistent. We address each in turn.

1. Consumer Welfare Has Gone the Way of the Dodo in Modern Economics

Welfare economists have long rejected this approach to normative welfare analysis from one hundred years ago. Modern Welfare Economics have moved far beyond this antiquated and flawed approach. For example, in 2015, Economics Nobel laureate Angus Deaton stated that “there is no valid theoretical or practical reason for ever integrating under a Marshallian demand curve” (the procedure for calculating consumer surplus).123Marco Becht, The Theory and Estimation of Individual and Social Welfare Measures, 9 J. Econ. Surv. 53 (1995) (quoting Angus Deaton, Demand Analysis, in 3 Handbook of Econometrics 1767, 1828 (Zvi Griliches & Michael D. Intriligator eds., 1986)). John Chipman and James Moore, two prominent welfare economists, concluded in their 1978 law review article that “the New Welfare Economics [which includes the surplus approach] must be considered a failure.”124John S. Chipman & James C. Moore, The New Welfare Economics 1939–1974, 19 Int’l Econ. Rev. 547, 548 (1978). See generally Ezra J. Mishan, Introduction to Normative Economics (1981); Robin Boadway & Neil Bruce, Welfare Economics (1984) (questioning the assumption that economists can aggregate all consumers into a single representative consumer for welfare measurement purposes); John M. Gowdy, The Revolution in Welfare Economics and Its Implications for Environmental Valuation and Policy, 80 Land Econ. 239 (2004) (arguing for a framework that moves beyond the “rational actor model” of new welfare economics). Antitrust economists assume welfare is equivalent with output. But modern welfare economists across the board reject this assumption.125Marc Fleurbaey & Didier Blanchet, Beyond GDP: Measuring Welfare and Assessing Sustainability 27 (2013). See generally Joseph E. Stiglitz, Amartya Sen & Jean-Paul Fitoussi, Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up (2010) (arguing for a more reliable benchmark of economic and social progress than gross domestic product); Charles Blackorby & David Donaldson, A Review Article: The Case Against the Use of the Sum of Compensating Variations in Cost-Benefit Analysis, 23 Can. J. Econ. 471 (1990) (arguing that consumer-surplus benchmarks critically fail to index criteria such as household welfare levels). Instead, welfare economists agree that distribution and inequality are critical dimensions of human welfare, as are choices of opportunities and democratic participation, the types of goals advocated by the New Brandeisians.126See generally Stiglitz et al., supra note 125 (discussing how GDP inaccurately measures economic well-being).

2. Consumer Welfare Contradicts Its Own Founders

The Consumer Welfare Standard, as formulated by the Chicago School, is even unfaithful to the original welfare arguments made by Marshall and Pigou over a hundred years ago. Marshall and Pigou never posited economic surplus as encompassing all of welfare, only the portion that they believed could be measured at the time. It was never proposed that policy would ignore other dimensions of welfare or distribution.127See Robert Cooter & Peter Rappoport, Were the Ordinalists Wrong About Welfare Economics?, 22 J. Econ. Lit. 507, 512 (1984); Theodore Levitt, Alfred Marshall: Victorian Relevance for Modern Economics, 90 Q.J. Econ. 425, 430 (1976). Pigou described in his definition of economic welfare that output can be considered a contribution to welfare only when distribution is constant and all other factors impacting welfare are unaffected: “It is evident that, provided the dividend accruing to the poor is not diminished, increases in the size of the aggregate national dividend [GDP], if they occur in isolation without anything else whatever happening, must involve increases in economic welfare.”128Arthur C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare 82 (4th ed. 1932); see Mark Glick, The Unsound Theory Behind the Consumer (and Total) Welfare Goal in Antitrust, 63 Antitrust Bull. 455, 465–67 (2018).

The Chicago School simply (and conveniently) dropped the critical caveats.129This simplification pervades industrial organization textbooks. For example, Jean Tirole writes: “In this book, I will treat income distribution as irrelevant. . . . I will focus on the efficiency of markets[.] . . . The ‘compensation principle’ of Hicks (1940) and Kaldor (1939) holds that we need only be concerned about efficiency; if total surplus increases, the winners can compensate the losers and everyone is made better off.” Tirole, supra note 91, at 12.

3. Consumer Welfare is Deeply and Irrevocably Flawed

The approach advanced by Marshall and Pigou suffered from several problems. For example, it relied on cardinal utility, it was a partial equilibrium approach, and it assumed constant and equal marginal utility of money.130See Glick, supra note 128, at 460–63. For this reason, following the publication of Vilfredo Pareto’s Manual of Political Economy, the economics profession adopted the Pareto Principle (also used to refer to optimality and efficiency) that a situation is an efficient improvement if there is a benefit to at least one individual while not making any other agent worse off.131Gregory J. Werden, Antitrust’s Rule of Reason: Only Competition Matters, 79 Antitrust L.J. 713, 714 (2014) (“To formalize such ideas, economists struggled in vain to sum the utilities of all individuals in the economy [without cardinal utility]. Economists then turned to the concept of Pareto optimality.”). Every major Ph.D.-level microeconomics textbook today adopts Pareto’s definition of efficiency.132See, e.g., Andreau Mas-Colell, Michael D. Whinston & Jerry R. Green, Microeconomic Theory 307 (1995) (“An economic outcome is said to be Pareto optimal if it is impossible to make some individuals better off without making some other individuals worse off.”); Hal R. Varian, Microeconomic Analysis 225 (3d ed. 1992); Geoffrey A. Jehle & Philip J. Reny, Advanced Microeconomic Theory 183 (3d ed. 2011). But the Pareto Principle is limiting. Few situations are distinguishable using the Pareto Principle, and there can be many non-comparable Pareto outcomes. It is never applicable when there are potential winners and losers from a policy. It therefore seems inapplicable to Article III “Cases” and “Controversies.”[mfn]U.S. Const. art. III, § 2.[/mfn] The set of points that are Pareto efficient is dependent on the original distribution, so equity and efficiency cannot be separated. As many philosophers have pointed out, Pareto Efficiency requires that perverse preferences do not exist, an assumption called the “monotonicity” assumption in welfare economics.133See, e.g., Hiroaki Hayakawa & Yiannis Venieris, Consumer Interdependence via Reference Groups, 85 J. Pol. Econ. 599, 612 (1977). Moreover, Pareto Efficiency assumes a consequentialist and welfarist moral epistemology.134See Matthew D. Adler, Well-being And Fair Distribution Beyond Cost Benefit Analysis 20–56 (2011). Despite these problems, most economists (including the authors) find Pareto Efficiency ethically appealing.135Jonathan B. Wight, The Ethics Behind Efficiency, 48 J. Econ. Educ. 15, 17–18, 24 (2017).

The Consumer Welfare Standard, however, is not based on Pareto Efficiency. In the late 1930s, economists realized that few policies could be assessed using Pareto Efficiency.136Nicholas Kaldor, Welfare Propositions of Economics and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility, 49 Econ. J. 549, 549 (1939) (“If the incomparability of utility to different individuals is strictly pressed, not only are the prescriptions of the welfare school ruled out, but all prescriptions whatever. The economist as an advisor is completely stultified . . . .”). Professors Nickolas Kaldor and John Hicks proposed the compensation test to replace the Pareto requirement of no losers.137John R. Hicks, The Rehabilitation of Consumers’ Surplus, 8 Rev. Econ. Stud. 108, 111 (1941). Under the compensation test, if losers could potentially be compensated by the winners, a change remained efficient even if no compensation occurred.138Id.; Kaldor, supra note 137, at 550. Professor A. Henderson and Hicks proposed the compensating variations (“CV”) and equivalent variations (“EV”) tests as money measures of welfare, recognizing that there is not a single measure of subjective value but instead two competing measures (willingness to pay for a price decrease and willingness to accept to in lieu of the price increase).139John R. Hicks, Value And Capital: An Inquiry into some Fundamental Principles of Economic Theory 40–41 (2d ed. 1946); A. Henderson, Consumer’s Surplus and the Compensating Variation, 8 Rev. Econ. Stud. 117, 117–18, 121 (1941); see Hicks, supra note 138, at 108.

Welfare economists soon recognized the numerous ethical problems and inconsistencies in this approach and have largely abandoned it. But it lives on as the Consumer Welfare Standard in antitrust for reasons that defy explanation. Among the many problems are the following:

(1) The two measures, CV and EV, can differ, leading to conflicting conclusions and can result in reversals and lack of transitivity. To avoid this possibility requires heroic assumptions.140Paul A. Samuelson, Evaluation of Real Income, 2 Oxford Econ. Papers 1, 2, 5, 9 (1950); W. M. Gorman, Community Preference Fields, 21 Econometrica 63, 66, 68, 80 (1953). Moreover, analysis of Robert Willig does not limit this problem to unrealistic scenarios. See Mark Glick, Gabriel A. Lozada & Darren Bush, Why Economists Should Support Populist Antitrust Goals, 2023 Utah L. Rev. 769, 802 (2023).

(2) Potential compensation does have the same attractive feature of Pareto Efficiency that no individuals are harmed and therefore does not increase welfare through preference satisfaction. In addition, Professors Robin Boadway and Neil Bruce further show that the Kaldor or Hicks approach may not pass a potential compensation test in any event.141Boadway & Bruce, supra note 124, at 265.

(3) Consumer preferences cannot be perverse, must be self-interested, and be the result of sufficient information. Otherwise, choices may not result in welfare increases.142See Daniel M. Hausman, Michael S. McPherson & Debra Satz, Economic Analysis, Moral Philosophy, and Public Policy 128–29 (2006); John Broome, Choice and Value in Economics, 30 Oxford Econ. Papers 313, 333 (1978); Tyler Cowen, The Scope and Limits of Preference Sovereignty, 9 Econ. & Phil. 253, 256 (1993); Robert H. Frank, Passions Within Reason: The Strategic Role of the Emotions 137–145 (1988).

(4) The theory is biased toward the interests of the rich and big business because it is assumed that the marginal utility (or social welfare equivalent) of money is constant and equal for everyone. This assumption is rejected by all welfare economists.143See, e.g., Blackorby & Donaldson, supra note 125, at 472, 491; Peter Hammond, Welfare Economics, in Issues In Contemporary Microeconomics and Welfare 405, 408 (George R. Feiwel ed., 1985); Matthew D. Adler, Measuring Social Welfare: An Introduction, 35–36 (2019).

The Consumer Welfare Standard contains all these flaws and more. For example, not all impacted individuals by a policy have standing. Their welfare is not considered. The defects in the Consumer Welfare Standard warrant its removal as a standard to judge antitrust policy goals. Only the New Brandeisians have taken this position.

B. The New Brandeisians’ Antitrust Goals Are Supported by Economic Evidence

In addition to evidence from legislative intent, economic research supports the New Brandeisians’ goals of political democracy and reducing inequality.144On the issue of legislative intent, see, e.g., Robert H. Lande & Sandeep Vaheesan, Preventing the Curse of Bigness Through Conglomerate Merger Legislation, 52 Ariz. St. L.J. 75, 82–84 (2020); Lina M. Khan & Sandeep Vaheesan, Market Power and Inequality: The Antitrust Counterrevolution and Its Discontents, 11 Harv. L. & Pol’y Rev. 235, 265–66 (2017). For example, in their comprehensive study of why some nations fail, Professors Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson identify inclusive economic and political institutions as the one common element of successful economies:

Central to our theory is the link between inclusive economic and political institutions and prosperity. Inclusive economic institutions that enforce property rights, create a level playing field, and encourage investments in new technologies and skills are more conducive to economic growth than extractive economic institutions . . . . Inclusive economic institutions are in turn supported by, and support, inclusive political institutions, that is, those that distribute political power widely in a pluralistic manner . . . .145Daron Acemoglu & James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty 429–30 (2012).

For Acemoglu and Robinson, an inclusive economy is one that is not dominated by a few large firms, and an inclusive political system is one in which political power is similarly dispersed.146Id. at 430. They argue that inclusive political institutions create successful economies by allowing the creative destruction of old technologies and the encouragement of new and better innovations (think the replacement of fossil fuels by more efficient climate-friendly technologies).147Id. Only when dominant firms unduly wield political power can rent-seeking and value-extraction be sustained.148Id. at 430–32.

Excessive political influence allows dominant firms to externalize costs. Dominant firms can outsource wages and benefits to smaller firms, and the public can be forced to bear the costs of environmental damage and any necessary social safety protections. Professor Fred Block describes the process as follows:

The more successful firms gradually get larger and larger, either through mergers and acquisitions or simply by driving their competitors out of the marketplace. As their size increases, they see the advantages of locking in profits by finding paths to profits that are protected from any kind of competition and by shifting costs onto others through sweating workers or contributing to environmental degradation. Since their size generates profits and political influence, they have both the incentive and the capacity to get political rulings that support these shortcuts to continuing profitability. Without strong democracy, this degenerative process saps the economy of its dynamism.149Block, supra note 12, at 75.

Block points out that “oligarchies will have slower rates of economic growth than egalitarian democracies”150Id. at 70. because once-dominant firms capture political power, they can blunt competitive challenges resulting in “little incentive to invest much in upgrading their production facilities.”151Id. As Block describes, “members of the existing elite might occasionally invest in something new, but this still means a much slower rate of change than occurs in more open [political] systems.”152Id. Block continues:

[I]t is almost always easier for firms to make profits by shifting costs onto others than by increasing efficiency. Under oligarchy, the dominant firms and families often shift costs onto employees by paying low wages and maintaining dirty and dangerous work conditions, or they shift costs onto the environment through dumping their waste into water, air, or landfills.153Id.

Democracy, in contrast, allows the other classes in society (e.g., smaller firms, workers, smaller agricultural interests, emerging firms) to penalize government officials that subsidize dominant firms, aid in large firm rent-seeking, and facilitate the imposition of unreasonable costs on the public.154Antitrust is concerned that higher prices reduce the consumption of preferred commodities by consumers. Concentrated political power has a similar impact. Large firms that capture undue political power will use that power to lower taxes and other costs, and increase their share of public goods. The classes and groups that are disempowered are left to consume a diminishing share of public goods.

In addition, research by welfare economists has shown that living under democratic institutions increases human welfare. Professor Bruno Frey summarizes this literature in his book, Happiness: A Revolution in Economics,155Bruno S. Frey, Happiness: A Revolution in Economics 61–67 (2008). “Overall, these results suggest that individuals living in countries with more extensive democratic institutions feel happier with their lives according to their own evaluation than individuals in more authoritarian countries.”156Id. at 64. See also Bruno S. Frey & Alois Stutzer, Happiness, Economy and Institutions, 110 Econ. J. 918, 925–26 (2000) (correlating democracy with life satisfaction in Switzerland). A similar case can be made for small businesses. See Matthias Benz & Bruno S. Frey, Being Independent is a Great Thing: Subjective Evaluations of Self-Employment and Hierarchy, 75 Economica 362, 367 (2008).

Likewise, extensive literature has shown that social inequality is related to increased mental illness, illegal drug use, lower life expectancy, greater violence, and lower social mobility.157See Richard Wilkinson & Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger 38–39 (2010). Social Inequality has also been linked to lower happiness and lower general trust. Shigehiro Oishi, Selin Kesebir & Ed Diener, Income Inequality and Happiness, 22 Psych. Sci. 1095, 1099 (2011). Indeed, inequality and governance are among the factors typically tracked by welfare economists as indicators of the state of a nation’s welfare.158See, e.g., Fleurbaey & Blanchet, supra note 125, at 29.

In a recent analysis by Michael Allen and his co-authors, they demonstrate how antitrust, democracy, and inequality are related. They find antitrust enforcement is facilitated by democracy and low inequality.159Michael O. Allen, Kenneth Scheve & David Stasavage, Democracy, Inequality, and Antitrust 15 (Feb. 3, 2023), https://perma.cc/FEZ5-MRVE. High-inequality democracies tend to get stuck with weak antitrust legislation because the power of big business prevents effective antitrust legislation and its enforcement.160Id. at 7.

III. Economic History Favors the New Brandeisians

The Chicago School and the Post-Chicago School offer little by way of explanation for the deterioration of economic performance since 1980. In a recent paper, Jon Baker describes the antitrust enforcement of the late 1930s and 1940s as an alternative to economic regulation in addressing the market power that resulted from the earlier period of laissez-faire.161Baker, supra note 8, at 711. He sees antitrust as a way to achieve “inclusive economic growth” by protecting private economic rights while providing a social safety net.162Id. at 717–18.